God Incarnation and Metaphysics Article Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analytic Philosophy and the Fall and Rise of the Kant–Hegel Tradition

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87272-0 - Analytic Philosophy and the Return of Hegelian Thought Paul Redding Excerpt More information INTRODUCTION: ANALYTIC PHILOSOPHY AND THE FALL AND RISE OF THE KANT–HEGEL TRADITION Should it come as a surprise when a technical work in the philosophy of language by a prominent analytic philosopher is described as ‘an attempt to usher analytic philosophy from its Kantian to its Hegelian stage’, as has 1 Robert Brandom’s Making It Explicit? It can if one has in mind a certain picture of the relation of analytic philosophy to ‘German idealism’. This particular picture has been called analytic philosophy’s ‘creation myth’, and it was effectively established by Bertrand Russell in his various accounts of 2 the birth of the ‘new philosophy’ around the turn of the twentieth century. It was towards the end of 1898 that Moore and I rebelled against both Kant and Hegel. Moore led the way, but I followed closely in his foot- steps. I think that the first published account of the new philosophy was 1 As does Richard Rorty in his ‘Introduction’ to Wilfrid Sellars, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind, with introduction by Richard Rorty and study guide by Robert Brandom (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997), pp. 8–9. 2 The phrase is from Steve Gerrard, ‘Desire and Desirability: Bradley, Russell, and Moore Versus Mill’ in W. W. Tait (ed.), Early Analytic Philosophy: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein (Chicago: Open Court, 1997): ‘The core of the myth (which has its origins in Russell’s memories) is that with philosophical argument aided by the new logic, Russell and Moore slew the dragon of British Idealism ...An additional aspect is that the war was mainly fought over two related doctrines of British Idealism ...The first doctrine is an extreme form of holism: abstraction is always falsification. -

PDF Version for Printing

Fermilab Today Thursday, March 27, 2008 Subscribe | Contact Fermilab Today | Archive | Classifieds Search Furlough Information Feature Fermilab Result of the Week Reminder: symmetry expands online Shedding new light An IDES representative will presence, features new blog on an old problem conduct the final on-site group meetings at 11 a.m. and noon in the Wilson Hall One West conference room on Friday, March 28. New furlough information, including an up-to-date Q&A section, appears on the furlough Web pages daily. symmetry magazine now provides more online content while it saves money by publishing fewer Layoff Information print issues. This figure shows the transverse photon New information on Fermilab From the symmetry editor: momentum in large extra dimension candidate layoffs, including an up-to-date events. The additional rate of signal events is This week's distribution of the new issue of Q&A section, appears on the shown in the open histogram along with the layoff Web pages daily. symmetry launches the next phase of the expected backgrounds. magazine's development. Our readers now Calendar use the magazine in different ways, and we When it comes to particle interactions, the are reaching a much larger audience. While force of gravity is an oddity. It is also entirely Thursday, March 27 readers are outspoken in wanting to keep the absent from the Standard Model theory. 10 a.m. print magazine, many of them are now more Although gravity is an undeniable force in our Presentations to the Physics comfortable reading online. everyday life and dominates interactions on the cosmological scale, it is by far the weakest Advisory Committee - Curia II Starting from this issue, we will publish six force at the particle level and has never been 1 p.m. -

WSRC3290 ASCP 2018 Conference Program FA.Indd

AUSTRALASIAN SOCIETY FOR CONTINENTAL PHILOSOPHY ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2018 AUSTRALASIAN SOCIETY FOR CONTINENTAL PHILOSOPHY ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF COUNTRY THANKS TO Western Sydney University would like to acknowledge the ≥ Professor Peter Hutchings, Dean of the School of Humanities Burramattagal people of the Darug tribe, who are the traditional and Communication Arts custodians of the land on which Western Sydney University at Jacinta Sassine and the student volunteers Parramatta stands. We respectfully acknowledge the Burramattagal ≥ people’s Ancestors and Elders, past and present and acknowledge ≥ Hannah Stark, Timothy Laurie and student volunteers their 60,000 year unceded occupation of these lands. who organized the PG event ≥ Panel organisers: Dr Suzi Adams and Dr Jeremy Smith; Professor WELCOME Thomas M. Besch; Professor Francesco Borghesi; Dr Sean Bowden; Associate Professor Diego Bubbio; Dr Millicent Churcher; Dr Richard The Conference Organising Committee for 2018 extends a warm Colledge; Dr Ingo Farin; Associate Professor Chris Fleming; Dr John welcome to all our international and Australian participants, and all Hadley; Professor Vanessa Lemm; Professor Li Zhi; Associate Professor others associated with the conference. The ASCP conference is this year hosted by Western Sydney University, at our new Parramatta David Macarthur; Associate Professor Sally Macarthur; Dr Jennifer City campus. The event has been planned and developed across Mensch; Professor Nick Mansfield; Dr Talia Morag; Associate Professor this year by members of the Philosophy Research Initiative. Eric S. Nelson; Professor Ping He; Dr Rebecca Hill; Associate Professor Janice Richardson and Dr Jon Rubin; Dr Marilyn Stendera; Dr Omid Tofighian; Professor Miguel Vatter and Dr Nicholas Heron; Dr Allison CONFERENCE ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Weir; Dr Magdalena Zolkos. -

In Mimetic Theory

Doubles, Narcissists, Victims, and Philosophers: Truth and “After Truth” in Mimetic Theory Scott Cowdell Many factors contribute to today’s “after truth” situation. Regarding Brexit, for instance, when populist nationalistic myth trumped entrenched economic rationalism, one commentator points to non-serious Tory media tarts like Boris Johnson overshadowing more serious policy contributors from the political left.1 And, from this side of the ditch, Kurt Anderson addresses a cultural history of programmatic American self-delusion in his bestseller Fantasyland.2 He points to America’s early-modern origins in dreams of non- existent Eldorado and projects of religious extremism, to its subsequent tastes for hucksterism and fundamentalism, to its widespread preference for the pleasure principle over the reality principle and, notably, to the key contribution of today’s culturally relativistic left-wing intellectuals whom he considers to be “useful idiots”. All this adds up to what Anderson calls America’s “fantasy industrial complex”. And, wherever you look, social media is supplanting traditional curated media, privatizing the commons and edging out the truth. It creates disconnected echo chambers of invincible ignorance rather than the global unity that Mark Zuckerberg used to say he believed in. The English political theologian Adrian Pabst describes the ideal politician in this brave new world as ideas-free, preferring targeted messaging based on computer algorithms over debate.3 Part of the problem is surely just how human beings are. The Nobel Prize-winning Israeli experimental psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, has shown that many real-life decisions are approached non-rationally. We are prone to biases and unreliable heuristics, we resist thinking carefully and taking stock, and we are not good natural statisticians when assessing financial risks. -

Dialectical Idealism and the Work of Lorenz Von Stein

JOHN WEISS DIALECTICAL IDEALISM AND THE WORK OF LORENZ VON STEIN Dialectical idealism as applied to social theory may be provisionally defined as an attempt to explain the evolution of Western society through the use of dialectical forms which rely upon the presumed motive power of spiritual, mental, or ideal forces. These forces are presumed to "realize themselves" in the historical process. Hegel and Fichte, of course, first made such concepts familiar. The mighty influence of Marx and dialectical materialism, which kept the form but not the idealism of the Hegelian dialectic, has accounted for a lasting eclipse of interest in this earlier form of dialectical social thought. It is at least partly a symptom of this general decline of interest in dialectical idealism that the work of Lorenz von Stein has become, until quite recently, all but forgotten to modern scholarship.1 German idealism was, after all, the great seminal force in nineteenth century social and historical thought. And Lorenz von Stein was one of the first and (barring Marx and Engels) perhaps the most able of those who applied Hegelian categories to the study of society and the social process. Furthermore, Stein's work is interesting to the student of German intellectual history, because it sheds much light on the themes and assumptions which were held by those young German intellectuals of the Vormdr^ who created, out of German idealism and their own revolutionary hopes, the tradition of modern German social theory and social radicalism. However ineffectual they appear to us now, the German Wars of Liberation and the Prussion Reform Era along with the Revolutions 1 It is encouraging to note that Kaethe Mengelberg, one of the most astute students of Stein's work, will soon publish a translation of his major work: Geschichte der Sozialen Bewegung in Frankreich. -

Hegel and Marx on Alienation a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University By

HEGEL AND MARX ON ALIENATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY SEVGİ DOĞAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY FEBRUARY 2008 Approval of the Graduate School of (Name of the Graduate School) Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Ahmet İnam Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts of Philosophy. Assist. Prof. Dr. Barış Parkan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Barış Parkan (METU, PHIL) Assist. Prof. Dr. Elif Çırakman (METU, PHIL) Assist. Prof. Dr. Çetin Türkyılmaz (Hacettepe U., PHIL) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Sevgi Doğan Signature : iii ABSTRACT HEGEL AND MARX ON ALIENATION Doğan, Sevgi M.A., Department of Philosophy Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Barış Parkan February 2008, 139 pages Is alienation a process of self-discovery or is it a loss of reality? The subject of this thesis is how alienation is discussed in Hegel and Marx’s philosophies in terms of this question. -

Downloadable and Ready Crucial to Our Understanding of What It Is to Be Physiology and Biophysics, and Director of the for Re-Use in Ways the Original Human

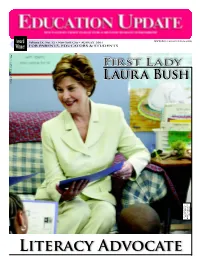

www.EDUCATIONUPDATE.com AwardAward Volume IX, No. 12 • New York City • AUGUST 2004 Winner FOR PARENTS, EDUCATORS & STUDENTS White House photo by Joyce Naltchayan First Lady Laura Bush U.S. POSTAGE PAID U.S. POSTAGE VOORHEES, NJ Permit No.500 PRSRT STD. PRSRT LITERACY ADVOCATE 2 SPOTLIGHT ON SCHOOLS ■ EDUCATION UPDATE ■ AUGUST 2004 Corporate Contributions to Education - Part I This Is The First In A Series On Corporate Contributions To Education, Interviewing Leaders Who Have Changed The Face Of Education In Our Nation DANIEL ROSE, CEO, ROSE ASSOCIATES FOCUSES ON HARLEM EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES FUND By JOAN BAUM, Ph.D. living in tough neighborhoods and wound up concentrating on “being effective at So what does a super-dynamic, impassioned, finding themselves in overcrowded the margin.” First HEAF took under its wing articulate humanitarian from a well known phil- classrooms. Of course, Rose is a real- the lowest-ranking public school in the city and anthropic family do when he becomes Chairman ist: He knows that the areas HEAF five years later moved it from having only 9 Emeritus, after having founded and funded a serves—Central Harlem, Washington percent of its students at grade level to 2/3rds. significant venture for educational reform? If Heights, the South Bronx—are rife Then HEAF turned its attention to a minority he’s Daniel Rose, of Rose Associates, Inc., he’s with conditions that all too easily school with 100 percent at or above grade level “bursting with pride” at having a distinguished breed negative peer pressure, poor but whose students were not successful in getting new team to whom he has passed the torch— self-esteem, and low aspirations and into the city’s premier public high schools. -

Publications for Paul Redding 2020 2019 2017 2016 2015

Publications for Paul Redding 2020 href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09672559.2019.1611079">[Mor Redding, P. (2020). Being the rope in a tug of war: M�rkus e Information]</a> and Rorty as readers of Hegel in the �70s, �80s and Redding, P. (2019). The Role of Philosophy in "Post-Truth" �90s. Thesis Eleven, 160(1), 22-33. <a Times. In Paolo Diego Bubbio, Jeff Malpas (Eds.), Why href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0725513620960008">[More Philosophy?, (pp. 81-101). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. Information]</a> <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110650990- Redding, P. (2020). Hegel and Recent Analytic Metaphysics. 009">[More Information]</a> In Marina F. Bykova, Kenneth R. Westphal (Eds.), The Redding, P. (2019). Time and Modality in Hegel's Account of Palgrave Hegel Handbook, (pp. 521-539). Cham: Palgrave Judgement. In Brian Ball and Christoph Schuringa (Eds.), The Macmillan. <a href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030- Act and Object of Judgment: Historical and Philosophical 26597-7_26">[More Information]</a> Perspectives, (pp. 91-109). New York: Routledge. <a Redding, P. (2020). The "Pittsburgh" Neo-Hegelianism of href="http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780429435317-5">[More Robert Brandom and John McDowell. In Marina F. Bykova, Information]</a> Kenneth R. Westphal (Eds.), The Palgrave Hegel Handbook, (pp. 559-571). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. <a 2017 href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26597-7_28">[More Redding, P. (2017). Aristotelian Master and Stoic Slave: From Information]</a> Epistemic Assimilation to Cognitive Transformation. In Rachel 2019 Zuckert, James Kreines (Eds.), Hegel on Philosophy in History, (pp. -

Religion and Representation in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 11-2017 The perversion of the absolute: religion and representation in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit Thomas Floyd Wright DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Wright, Thomas Floyd, "The perversion of the absolute: religion and representation in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit" (2017). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 240. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/240 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PERVERSION OF THE ABSOLUTE Religion and Representation in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 BY Thomas Floyd Wright Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hegel contra Theology . 1 1.2 Marx, Ante-Hegel . 5 1.3 Hegel, post Hegel mortum . 11 1.4 Speculation and perversion . 16 2 The perversion of identity 22 2.1 The evil of ontotheology . 22 2.2 The perversion of desire: Augustine . 26 2.3 The perversion of speech: Hobbes . 30 2.4 The perversion of reason: Kant . -

On Hegel on Buddhism Mario D'amato Rollins College, [email protected]

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Student-Faculty Collaborative Research 1-1-2011 The pS ecter of Nihilism: On Hegel on Buddhism Mario D'Amato Rollins College, [email protected] Robert T. Moore Rollins College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/stud_fac Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Published In D'Amato, Mario and Moore, Robert T., "The peS cter of Nihilism: On Hegel on Buddhism" (2011). Student-Faculty Collaborative Research. Paper 28. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/stud_fac/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student-Faculty Collaborative Research by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Specter of Nihilism: On Hegel on Buddhism ∗ Mario D’Amato and Robert T. Moore Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) is renowned as one of the most complex and comprehensive modern philosophers. The goal of his philosophical system is nothing less than to explain the interrelationships among all the multifarious aspects of the whole of reality, including the entire array of historical religions. But Hegel’s dialectical method has been criticized as being speculative and idealistic, and his interpretation of religion has been written off by some as an overly ambitious attempt to force the historical religions into the confines of a predetermined hierarchical scheme. As for his perspective on Buddhism, Hegel interprets it as a form of nihilism, stating that for Buddhism, “the ultimate or highest [reality] is…nothing or not- being” and the “state of negation is the highest state: one must immerse oneself in this nothing, in the eternal tranquillity of the nothing generally” (LPR 253).1 Hegel’s interpretation of Buddhism has of course been appropriately criticized in recent scholarship, most ably by Roger-Pol Droit in his work The Cult of Nothingness: The Philosophers and the Buddha (2003). -

Procedura Di Valutazione Comparativa Per La Stipula Di N

PROCEDURA DI VALUTAZIONE COMPARATIVA PER LA STIPULA DI N. 1 CONTRATTO DI DIRITTO PRIVATO PER RICERCATORE A TEMPO DETERMINATO, AI SENSI DELL’ART. 24, COMMA 3, LETT. B) DELLA LEGGE 30 DICEMBRE 2010, N. 240, PER IL S.C. 11/C1 - FILOSOFIA TEORETICA PROFILO RICHIESTO S.S.D. M-FIL/01 - FILOSOFIA TEORETICA DIPARTIMENTO DI CIVILTÀ ANTICHE E MODERNE PRESSO L’UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MESSINA VERBALE 2 (Valutazione preliminare dei candidati e ammissione alla discussione pubblica) L’anno 2020 il giorno 11 del mese di novembre alle ore 17:00 si riunisce al completo, per via telematica, la Commissione giudicatrice, nominata con D.R. prot. n. 0094164 del 8/10/2020, pubblicato sul sito internet dell’Università di Messina, della valutazione comparativa in epigrafe, per procedere alla valutazione comparativa dei titoli, dei curricula e della produzione scientifica dei candidati, ivi compresa la tesi di dottorato. Sono presenti i sotto elencati commissari: Prof. Gianluca Cuozzo (Università degli studi di Torino) Prof. Donatella Di Cesare (Università Sapienza di Roma) Prof. Caterina Resta (Università degli studi di Messina) Il Presidente della Commissione comunica che sono trascorsi almeno 7 giorni dalla pubblicizzazione dei criteri e che la Commissione può legittimamente proseguire i lavori. I componenti accedono, tramite le proprie credenziali, alla piattaforma informatica https://istanze.unime.it/ e prendono visione dell’elenco dei candidati che risultano essere (in ordine alfabetico): 1. Angeloni Roberto 2. Bazzoni Bueno André 3. Bubbio Paolo Diego 4. Caffo Leonardo 5. Cerasi Enrico 6. Croci Federico 7. Forlè Francesca 8. Fulco Rita 9. Marafioti Rosa Maria 10. Pace Giannotta Andrea Sebastiano 11. -

JOSEPH DE MAISTRE and ITALY Marco Ravera It Is Very Likely That Joseph De Maistre Would Not Have Been Very Much Interested in Th

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Research Information System University of Turin JOSEPH DE MAISTRE AND ITALY Marco Ravera It is very likely that Joseph de Maistre would not have been very much interested in the subject of the reception of his own thought in Italy.1 He did not consider himself Italian—and, in spite of his being Francophone, he did not consider himself French either—but only and exclusively Savoyard (or rather, in the last phase of his life, Savoyard and European at the same time, but certainly not Italian). His eyes and his attention were always drawn to France; and the early impulses for the national unity of Italy that happened a few years aft er the Restoration—a legacy of that Napoleonic epos which he abhorred so much—left him perplexed and astonished, rather than disturbed and troubled. It is true that, given that he died at the end of February 1821, he could not witness (or, we might say, he was spared the sight of) the early risings for unity. However, his opinion in this respect is con- densed, through refl ections enriched by that sarcastic irony which dis- tinguishes several of his writings, in some famous claims included in the letter to the marquis d’Azeglio2 of 21 February 1821—that is, three days before his death—where, with ill-concealed scepticism, he won- ders whether and to what extent one can call himself ‘Italian’. Aft er hav- ing thanked his correspondent for having sent to him a basketful of fruit, the nearly expiring lion still shows his claws and, taking his cue from some considerations on Piedmont and Italy made by d’Azeglio in the letter that accompanied the gift , added long refl ections on this sub- ject.