Street Music, City Rhythms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September-October 2019

VOLUME 27, ISSUE 2 GUILDERLANDLIBRARY.ORG SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2019 UHLS EXPEDITION PARTY The Crossings - Colonie Tuesday, September 10 @ 4-7 pm Did you have fun during All concerts @ 2 pm the Library Expedition? SEPTEMBER 22: We did too! Come visit the OLD TIME DANCE BAND Upper Hudson libraries all Relive the nostalgic Big Band over again at The Cross- era, or discover this mood- ings in Colonie. There inducing music afresh as this will be doughnuts, cider, eclectic ensemble performs activities for kids, and a Dixieland, Hot Jazz, and Early whole lot of fun! Be sure Swing-style classics. to stop by the GPL table too. Bring your lawn chairs and enjoy the evening with us. Please register at: https://tinyurl.com/ OCTOBER 13: THE KENNEDYS ExpeditionParty if you plan on attending. We’re thrilled to be hosting the renowned folk-rock band, GAME ON! The Kennedys! Pete and Tuesday, September 3 @ 6:30 pm Maura Kennedy are perhaps best known for having been Are you a board game fanatic? with Nanci Griffith’s band, Ever wonder what goes into making but their musical career a board game? Local expert, Peter spans 20+ years, and together they have recorded more McPherson, will tell us how his new than a dozen albums. Their most recent album, Safe Until board game, “Tiny Towns,” got made! Tomorrow, came out in 2018. Don’t miss this very special He’ll share his tips, tricks, and performance! knowledge about the process from start to finish. “Tiny Towns” has New Music Series! GPL CABARET excellent reviews and ratings on both Jeanne O’Connor Quartet Boardgamegeek.com and Amazon. -

Ic/Record Industry July 12, 1975 $1.50 Albums Jefferson Starship

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS IC/RECORD INDUSTRY JULY 12, 1975 $1.50 SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS ZZ TOP, "TUSH" (prod. by Bill Ham) (Hamstein, BEVERLY BREMERS, "WHAT I DID FOR LOVE" JEFFERSON STARSHIP, "RED OCTOPUS." BMI). That little of band from (prod. by Charlie Calello/Mickey Balin's back and all involved are at JEFFERSON Texas had a considerable top 40 Eichner( (Wren, BMI/American Com- their best; this album is remarkable, 40-1/10 STARSHIP showdown with "La Grange" from pass, ASCAP). First female treat- and will inevitably find itself in a their "Tres Hombres" album. The ment of the super ballad from the charttopping slot. Prepare to be en- long-awaited follow-up from the score of the most heralded musical veloped in the love theme: the Bolin - mammoth "Fandango" set comes in of the season, "A Chorus Line." authored "Miracles" is wrapped in a tight little hard rock package, lust Lady who scored with "Don't Say lyrical and melodic grace; "Play on waiting to be let loose to boogie, You Don't Remember" doin' every- Love" and "Tumblin" hit hard on all boogie, boogie! London 5N 220. thing right! Columbia 3 10180. levels. Grunt BFL1 0999 (RCA) (6.98). RED OCTOPUS TAVARES, "IT ONLY TAKES A MINUTE" (prod. CARL ORFF/INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE, ERIC BURDON BAND, "STOP." That by Dennis Lambert & Brian Potter/ "STREET SONG" (prod. by Harmonia Burdon-branded electrified energy satu- OHaven Prod.) (ABC Dunhill/One of a Mundi) (no pub. info). Few classical rates the grooves with the intense Kind, BMI). Most consistent r&b hit - singles are released and fewer still headiness that has become his trade- makers at the Tower advance their prove themselves. -

Journey Don't Stop Believin' / the Journey Story (An Audio Biography) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Journey Don't Stop Believin' / The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Non Music Album: Don't Stop Believin' / The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) Country: UK Released: 1982 Style: Pop Rock, Spoken Word, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1303 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1911 mb WMA version RAR size: 1118 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 412 Other Formats: MOD MP4 MP1 AAC MIDI TTA XM Tracklist Hide Credits Don't Stop Believin' A Producer – Kevin Elson, Mike StoneWritten-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. 4:08 Perry* The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) In The Morning B1 Written-By – G. Rolie*, R. Valory* To Play Some Music B2 Written-By – G. Rolie*, N. Schon* Saturday Nite B3 Written-By – Gregg Rolie Wheel In The Sky B4 Written-By – D. Valory*, Schon*, Fleischman* Feeling That Way B5 Written-By – Dunbar*, Rolie*, Perry* Anytime B6 Written-By – Rolie*, N. Schon*, Fleischman*, Silver*, R. Valory* Lovin' Touchin' Squeezin' B7 Written-By – S. Perry* When You're Alone (It Ain't Easy) B8 Written-By – N. Schon*, S. Perry* Someday Soon B9 Written-By – G. Rolie*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Any Way You Want It B10 Written-By – N. Schon*, S. Perry* Stone In Love B11 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Who's Crying Now B12 Written-By – J. Cain*, S. Perry* Mother Father B13 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Don't Stop Believin' B14 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – CBS Records Copyright (c) – CBS Records Pressed By – Orlake Records Published By – Screen Gems-EMI Music Ltd. -

ÖPPET HUS I RIKSDAGEN Program 27 APRIL 2019

ÖPPET HUS I RIKSDAGEN 27 APRIL 2019 Program 2 | Öppet hus i riksdagen Följ vad som händer i riksdagen riksdagen.se På riksdagens webbplats hittar du allt om riksdagen och riksdagens arbete. Ja, må den leva! Demokratin uti hundrade år Sveriges riksdag uppmärksammar och firar demokratin under åren 2018– 2022. Läs mer på firademokratin.riksdagen.se Twitter På Twitter kan du bevaka riksdagens arbete via kontot @Sverigesriksdag. Youtube På Sveriges riksdags officiella Youtube-kanal kan du uppleva riksdagen inifrån och lära dig mer om hur riksdagens arbete och svensk demokrati fungerar. Kontakta riksdagen Ledamöter och partier Kontaktuppgifter till partier och riksdagsledamöter hittar du på riksdagen.se. Frågor om riksdagen och om EU? Ring 020-349 000 eller e-posta till [email protected]. Besök riksdagen Följ debatter och utfrågningar Följ debatter, omröstningar och öppna utfrågningar på plats i Riksdagshuset. De går också att följa via webb-tv på riksdagen.se. Guidade visningar Riksdagshuset visas lördagar och söndagar på svenska och engelska. På måndagar är det konstvisning. Riksdagsbiblioteket Riksdagsbiblioteket i Gamla stan är ett samhällsvetenskapligt bibliotek som är öppet för alla. Telefon 020-555 000. E-post [email protected] Öppet hus i riksdagen | 3 Fira demokratin! Riksdagens rum gömmer berättelser om mod, envishet, idogt arbete och goda gärningar. Vi öppnar upp för spännande samtal om våra grundlagar, riksdagens historia och budgetarbetet, om hjältar och pionjärer och den svenska demokratin igår, idag och imorgon. Ta chansen att uppleva din riksdag! 4 | Öppet hus i riksdagen Program i Västra riksdagshuset 18–22 18–22 Demokratitorg med kunskapsmingel 1 Mingla med riksdagens tjänstemän och ledamöter. -

Exploring the Hip-Hop Culture Experience in a British Online Community

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2010 Virtual Hood: Exploring The Hip-hop Culture Experience In A British Online Community. Natalia Cherjovsky University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology of Culture Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cherjovsky, Natalia, "Virtual Hood: Exploring The Hip-hop Culture Experience In A British Online Community." (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4199. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4199 VIRTUAL HOOD: EXPLORING THE HIP-HOP CULTURE EXPERIENCE IN A BRITISH ONLINE COMMUNITY by NATALIA CHERJOVSKY B.S. Hunter College, 1999 M.A. Rollins College, 2003 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2010 Major Professor: Anthony Grajeda © 2010 Natalia Cherjovsky ii ABSTRACT In this fast-paced, globalized world, certain online sites represent a hybrid personal- public sphere–where like-minded people commune regardless of physical distance, time difference, or lack of synchronicity. Sites that feature chat rooms and forums can offer a deep- rooted sense of community and facilitate the forging of relationships and cultivation of ideologies. -

February 21, 2002 TABLE of CONTENTS DUKE DAYS EVENTS CALENDAR THURSDAY, FEB

■ Page 13 ■ Past 19 | Pap 15 Early bird catches the worm Dlamand lakes Iran Man 3ournies Sludtnts mi professors share their CtfehratiM diversity iunior Brent Metheny modeLs his game after m Different paths lead to a common destination. In stories *n& habits of waking before COLOR his baseball idol, former Baltimore Orioles celebration of Black History Month, explore tlie the sun. third baseman Col Ripken jr. journies of several African-American students. fames Madison University Today: Partly cloudy Hiati: 57 THE REEZE - Low: 32 i.i„- ;'i Thui>tiiiu, I cbiittini 21, 201)2 Program Root root root for the home team Junior second teaches baseman Mitch Rigsby was 2 (or 5 at freshmen the plate and scored three of the leadership Diamond Dukes' 17 Bi DAVID CLEMENTSON runs. Senior senior writer designated All freshmen are invited to hitter Steve apply for one of 32 spots on a Ballowe and free leadership getaway called sophomore Ropes and Hopes, being right fielder offered during the spring Alan Lmdsey MBIMter for the first time. each hit a 'It was an amazing experi- home run. ence," said sophomore adding to Jennifer Terrill, who attended JMU s deci- sive 17-6 vic- the trip in September 2000 and tory over will be ■ leader on the trip this George semester It I was a freshman Washington again, i would not miss this University opportunity." Tuesday. Sophomore Jessica Maxwell, who also will help lead the trip this iimtttai after attending as a fresh- man in 2000, said, "Ropes and Hopes enhanced my life. My cloaesl mends are those I met through Ropes and Hopes. -

1980:147 Utlåtande Angående Förvärv Och Upplåtelse Av Fastigheterna RIII Mullvaden Första 13 Och 23 På Södermalm

Utl. 1980:147 RIII 1244 1980:147 Utlåtande angående förvärv och upplåtelse av fastigheterna RIII Mullvaden Första 13 och 23 på Södermalm Fastighetsnämnden har i skrivelse till kommunfullmäktige den 29 januari 1980 anmält att nämnden samma dag — i enlighet med fastighetskontorets hemställan i ett av kontoret den 11 december 1979 avgivet tjänsteutlåtande — beslutat dels för sin del godkänna ett utlåtandet bilagt, med AB Svenska Bostäder villkorligt träffat avtal angående förvärv 'åt kommunen av rubricerade fastigheter för en köpeskilling av 2 225 000 kronor, dels för sin del godkänna utlåtandet bilagda, med AB Svenska Bostäder upprättade förslag till överenskommelser och tomträttsavtal rörande upplåtelse till bolaget av de ifrågavarande fastigheterna samt därigenom underställt köpeavtalet med tillhörande överenskommelser kommunfullmäktiges prövning före den 1 april 1980. Nämnden har härutöver för sin del anfört följande. Nämnden förutsätter att fastigheterna Mullvaden Första 13 och 23 i enlighet med fastighetsnämndens beslut 1977-12-06 saneras genom ombyggnad. Fastighetskontorets tjänsteutlåtande är av i huvudsak följande lydelse. Allmänt Kvarteret Mullvaden Första begränsas av Hornsgatan—Timmermansgatan—Krukmakarga- tan och Torkel Knutssonsgatan. Kvarteret består f. n. av 14 fastigheter. Av dessa äger AB Svenska Bostäder fastigheterna Mullvaden Första 7, 13, 16-21 och 23 (nie fastigheter). Kommunen äger fastigheten Mullvaden Första 22 som dock är upplåten till AB Svenska Bostäder med tomträtt sedan 1975-01-01. Fastigheterna Mullvaden Första 15, 24-26 är privatägda (se karta bilaga 1; ej tryckt). Bolagets fastighetsförvärv inom kvarteret ägde rum under åren 1973-1975. Tidigare beslut I november 1977 framlade fastighetskontoret sin "Utredningsrapport angående bebyggel- sen inom delar av kvarteren Gropen, Mullvaden Första och Ormen Större" för fastighets- nämnden. -

“The Greatest Gift Is the Realization That Life Does Not Consist Either In

“The greatest gift is the realization that life does not consist either in wallowing in the past or peering anxiously into the future; and it is appalling to contemplate the great number of often painful steps by which ones arrives at a truth so old, so obvious, and so frequently expressed. It is good for one to appreciate that life is now. Whatever it offers, little or much, life is now –this day-this hour.” Charles Macomb Flandrau Ernest Hemingway drank here. Cuban revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Che Guevera drank here. A longhaired young hippie musician named Jimmy Buffett drank and performed here, too. From the 1930’s through today this rustic dive bar has seen more than its share of the famous and the infamous. It’s a little joint called Capt. Tony’s in Key West, Florida. Eighty-seven-year-old Anthony ‘Capt. Tony’ Tarracino has been the owner and proprietor of this boozy establishment since 1959. It seems Tony, as a young mobster, got himself into some serious trouble with ‘the family’ back in New Jersey and needed to lay low for a while. In those days, the mosquito invested ‘keys’ (or islands) on the southernmost end of Florida’s coastline was a fine place for wise guys on the lam to hide out. And this was well before the tee-shirt shops, restaurants, bars, art galleries, charming B&B’s and quaint hotels turned Key West into a serious year-round tourist destination. Sure, there were some ‘artsy’ types like Hemingway and Tennessee Williams living in Key West during the late 50’s when Tony bought the bar, but it was a seaside shanty town where muscular hard-working men in shrimp boats and cutters fished all day for a living. -

Vård Och Underhåll Av Fastigheter I Gamla Stan

Vård och underhåll av fastigheter i Gamla stan Stadsmuseet rapporterar | 87 Omslagsbild: Mattias Ek år 2015, SSM_10007263 Stadsmuseet Box 15025 104 65 Stockholm Rapportförfattare: Kersti Lilja Foto: Mattias Ek (där annat inte anges) Grafisk form: Cina Stegfors Tryckeri: Vitt grafiska, 2016 Publicering: 2016 ISBN 978-91-87287-57-2 © Stadsmuseet Förord Stadsmuseet i Stockholm har under 2014 och 2015 tagit fram föreliggande skrift, för att svara på de mest grundläggande av de många frågor om ombyggnader, renovering, vård och underhåll av Gamla stans bebyggelse som kommer till museets antikvarier. Rapporten har tagits fram av Kersti Lilja vid Kulturmiljöenheten med stöd av expertis från olika områden, inom och utom museet. För bildmaterialet ansvarar Stads- museets fotografer där annat inte anges. Arbetet har delvis finansierats med Kulturmiljöbidrag från Länsstyrelsen i Stockholm. Stockholm november 2015 Ann-Charlotte Backlund Stadsantikvarie Innehåll Vård och underhåll av fastigheter i Gamla stan .................................5 1 Inledning ........................................................................................5 2 Gamla stans historia .........................................................................6 3 Kulturhistoriska värden ...................................................................9 4 Regelverk ..................................................................................... 10 4.1 Ändring av byggnad ................................................................ 11 4.2 Vem vänder man sig till -

Use of Reflexive Thinking in Music Therapy to Understand the Therapeutic Process; Moments of Clarity, Self-Criticism: an Autoethnography

Qualitative Inquiries in Music Therapy 2018: Volume 13 (1), pp. Barcelona Publishers USE OF REFLEXIVE THINKING IN MUSIC THERAPY TO UNDERSTAND THE THERAPEUTIC PROCESS; MOMENTS OF CLARITY, SELF-CRITICISM: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHY Demeko Freeman, MMT, MT-BC ABSTRACT This research followed the phenomenological tradition to deliver an autoethnographic account of my experience as a music therapist working with people living with dementia. My aim was to challenge socio-cultural stigmas surrounding dementia as well as extend the sources of “truth” in regard to epistemological and ontological stances. The autoethnography presented a reflective examination through story of my daily life at a residential treatment facility. In this paper I explore encounters with residents and staff in an effort to better understand myself as a clinician and the therapeutic process. This process included decisions I made, the rationale for those decisions, and the evolution of the relationships. PRELUDE The Missing Person One rarely conducts research that is of no personal interest or gain. Realistically, the researcher’s influence will always be present in the research, as the foundation of the research question comes from the researcher’s personal curiosity to understand the phenomena under investigation (Muncey, 2010). The curiosity that propels research may stem from the memory of a loved one, a personal or professional interaction with another human being, or academic discourse. Aigen (2015) states that researchers, “are passionate advocates for particular theories and these theoretical commitments influence how facts are construed” (p. 12). Aigen further expresses that those in favor of a theory or stance are more likely to present findings that confirm it, while opponents of a theory will do the opposite. -

To Assist You in Complying with the Reporting Requirements for Children's Television

April 1, 2016 Dear Affiliate Partner: To assist you in complying with the reporting requirements for children’s television and the requirement that stations air “core” children’s programming, we are providing you with episode-specific descriptions (the ‘NBC Kids” educational and informational programming block) as set forth in the attached Community Relations Quarterly Children’s Programming Report for the 1st quarter of 2016. The report includes information to help prepare FCC Form 398. Please note that we have not included the specific dates and times for each of the programs as that may be station-specific. This report is divided into the following categories: 1. Educational Objectives: NBC Kids for both 1st quarter 2016 and 2nd quarter 2016. 2. Core programming: Regularly scheduled programming furnished by the NBC Network that is specifically designed to serve the educational and informational needs of children 16 and under. Each of these programs is identified on-air as educational and informational with the “E/I” icon, and is similarly identified to the national listing services. To assist stations with the preemption report section of FCC Form 398, we have added specific episode numbers. Please note that the age target for NBC Kids programming is identified as 2-5 years old. 3. Other programming: Programming furnished by the NBC Network that contributes to the educational and informational needs of children 16 and under, but is not specifically designed to meet the educational and informational needs of children. 4. Public service announcements targeted to children 16 and under. 5. Non-broadcast efforts that enhance the educational and informational value of NBC Network programming to children. -

~VI:R MADI:!!! Local HOT£S • Local Spotlight' • Local SHOWS • Local Recordiftgs Iday \ Open House I I

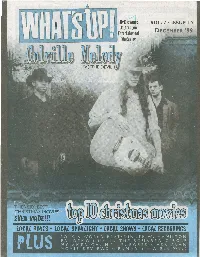

7 Belli11gham s VOL. 2 • ISSUE I 0 tJ Alternative . rl1tertail1mel1t DECEMBER '99 Magazil1e ~~~~ CH MOVIES ~VI:R MADI:!!! lOCAl HOT£S • lOCAl SPOTliGHT' • lOCAl SHOWS • lOCAl RECORDiftGS iDay \ Open House I I . We're Doing It Again!!! Saturday Dec. 11th Enter to Win an iMac TM DV! Entries taken all week long Drawing will be at noon on Saturday, Dec. 11th We had a great turn-out on our first iDay, so we've planned another one! There are In-Store Specials and Seminars running all day! Come in and see how to edit full screen video with iMovie ™on an iMac™DV! Alabama alpha tech Street .... COMPUTERS Q) ~ t~~;St (;) Virr). S U5 ~ mra t ~ 1 :§0 U5 alpha tech E ~ KentuckySt 0 AuthorizedReseller and Service Provider ~ ~ COMPUTERS. COM Iowa / U5 ;:r--- Street (360) 671-2334 • (800) 438-3216 ~"" lit Mac I ~ld), 2300 James Street • Belingham, WA Exit254 www.alphatechcomputers.com C§) ti Apple Specialist © 1999 Apple Computers, Inc. All rights reserved. The Apple logo is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. LOCAL NOTES ............................. .4 LOCAL SPOTLIGHT .................... 5 LOCAL SHOWS ........................ 6-7 LOCAL RECORDINGS ............ 8-9 TOP I 0 CHRISTMAS MOVIE RENTALS ••••••.••••.•••.•••• 10-11 COLVILLE MELODY •••••••••••••• 12-15 FOLKANDWORLD BEAT .......... I6 MOVIE REVIEWS .............................. 17 DINNER WITH HAMILTON ........ I8 P.INTHE SQUARED CIRCLE .. 19 MY AMERICA, MY NEUROSES 20 ASKALAN .................................... 21 FUNNY (IN A BAD WAY) ........ 22 CALENDAR .................................