© 2008 Saladin M. Ambar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strengthening America's Hunting Heritage and Wildlife Conservation

Strengthening America’s Hunting Heritage and Wildlife Conservation in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities Sporting Conservation Council Strengthening America’s Hunting Heritage and Wildlife Conservation in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities Strengthening America’s Hunting Heritage and Wildlife Conservation in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities Sporting Conservation Council Bob Model, Chair Jeff Crane, Vice Chair John Baughman Peter J. Dart Dan Dessecker Rob Keck Steve Mealey Susan Recce Merle Shepard Christine L. Thomas John Tomke Steve Williams Edited and produced by Joanne Nobile and Mark Damian Duda Responsive Management The views contained in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Government. Cover photo © Ducks Unlimited Table of Contents Preface vii Executive Summary 1 The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation: Enduring Achievement and Legacy 7 S.P. Mahoney, V. Geist, J. Organ, R. Regan, G.R. Batcheller, R.D. Sparrowe, J.E. McDonald, C. Bambery, J. Dart, J.E. Kennamer, R. Keck, D. Hobbs, D. Fielder, G. DeGayner, and J. Frampton Federal, State, and Tribal Coordination 25 Chair and Author: S. Williams Contributor: S. Mealey Wildlife Habitat Conservation 31 Chair: D. Dessecker Authors: D. Dessecker, J. Bullock, J. Cook, J. Pedersen, R. Riggs, R. Rogers, S. Williamson, and S. Yaich Coordinating Oil and Gas Development and Wildlife Conservation 43 Chair: S. Mealey Authors: S. Mealey, J. Prukop, J. Baughman, and J. Emmerich Climate Change and Wildlife 49 Chair: S. Mealey Authors: S. Mealey, S. Roosevelt, D. Botkin, and M. Fleagle Funding the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation in the United States 57 Chairs: John Baughman and Merle Shepard Authors: J. -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

The Governors of New Jersey' Michael J

History Faculty Publications History Summer 2015 Governing New Jersey: Reflections on the Publication of a Revised and Expanded Edition of 'The Governors of New Jersey' Michael J. Birkner Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Birkner, Michael J. "Governing New Jersey: Reflections on the Publication of a Revised and Expanded Edition of 'The Governors of New Jersey.'" New Jersey Studies 1.1 (Summer 2015), 1-17. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/57 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Governing New Jersey: Reflections on the Publication of a Revised and Expanded Edition of 'The Governors of New Jersey' Abstract New Jersey’s chief executive enjoys more authority than any but a handful of governors in the United States. Historically speaking, however, New Jersey’s governors exercised less influence than met the eye. In the colonial period few proprietary or royal governors were able to make policy in the face of combative assemblies. The Revolutionary generation’s hostility to executive power contributed to a weak governor system that carried over into the 19th and 20th centuries, until the Constitution was thoroughly revised in 1947. -

Topics in Us Government and Politics: American Political Development

POL 433/USA 403: TOPICS IN U.S. GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS: AMERICAN POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO WINTER 2019 Dr. Connor Ewing [email protected] Schedule: Monday 10:00am-12:00pm Location: OI 7192 Office Hours: Mon. & Tues. 12:00-2:00 pm, Larkin 215 Course Description This course explores the substance, nature, and study of American political development. It will begin by examining the methodology, mechanisms, and patterns of American political development from the founding to the present. Emphasis will be placed on divergent perspectives on the nature of political development, particularly narratives of continuity and discontinuity. Taking an institution-based approach, the course will then examine the central institutions of American politics and how they have developed over the course of American political history. Relevant to these institutional developments are a host of topics that students will have the opportunity to explore further in various written assignments. This include, but are not limited to, the following: the Constitution and the founding; political economy, trade, and industrialization; bureaucracy and administration; citizenship and inclusion; race and civil rights; law and legal development; and political parties. Course Objectives This course is intended to: • provide students with an understanding of key themes in and approaches to American political development; • expose students to multiple methods of political analysis, with an emphasis on the relationship and tensions between qualitative and quantitative methods; and • develop written and oral communication skills through regular classroom discussions and a range of writing assignments. Course Texts • The Search for American Political Development, Karen Orren and Stephen Skowronek (Yale University Press, 2004) • The Legacies of Losing, Nicole Mellow and Jeffrey Tulis (University of Chicago Press, 2018) All other readings will be available on the course website. -

A£F>L*JL*Cm Order B£Caf

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS OF COLLECTION: Dix, John A. - Papers SOURCE; Deposit - Mrs. Sophie Dix - 1950 SUBJECT: Correspondence of John Adams Dix; also some of John I, Morgan papers. DATES COVERED! 1813 - 1S?9 NUMBER OF ITEMS; ca 1226 STATUSs (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged! Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: \ff- boxes Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Special Collections CALL-NUMBER Spec Ms Con Dix RESTRICTIONS ON USE IUrftiente WBO fry-win luua and o«i<n'udllw^"ggftotgrB| DESCRIPTION- a£f>l*JL*cM order b£caf Personal correspondence and papers of the American statesman, John Adams Dix (1798-1879). The collection is composed mainly of letters to and by Mr. Dix, beginning in 1813 and continuing throughout his lifetime. ihe correspondence j/hich doubtless has been jpreserired selectiyely is almost entirely "with prominent public figures of the period: military, political and literary men. In addition to the correspondence are miscellaneous papers, speeches, essays, clippings and leaflets; includes also a small file (38 items) of the corres- pondence and papers of John I. !.'organ (1787-1S53). The collection has a calendar index. JAAI t95s FOR A LIST OF COLLECTION SEE FOLLOWING^ PAGES. Collection arranged aiphabetic^ll by correspondent General John A Dix -w, ^ collect.ion is ,rran -ei alpha-- hy c o " r? rr ondf n t ra t he r r;: • n i n niiinrric3l '^rdFr. 1C *JOT • ive *hc: George C Shattuck 3 far 1815 , Ai. JAD to George C Shattuek 20 Apr 1813 V..- ~"fn ' a r- ;in 3. -

10.1057/9780230282940.Pdf

St Antony’s Series General Editor: Jan Zielonka (2004– ), Fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford Othon Anastasakis, Research Fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford and Director of South East European Studies at Oxford Recent titles include: Julie Newton and William Tompson (editors) INSTITUTIONS, IDEAS AND LEADERSHIP IN RUSSIAN POLITICS Celia Kerslake , Kerem Oˇktem, and Philip Robins (editors) TURKEY’S ENGAGEMENT WITH MODERNITY Conflict and Change in the Twentieth Century Paradorn Rangsimaporn RUSSIA AS AN ASPIRING GREAT POWER IN EAST ASIA Perceptions and Policies from Yeltsin to Putin Motti Golani THE END OF THE BRITISH MANDATE FOR PALESTINE, 1948 The Diary of Sir Henry Gurney Demetra Tzanaki WOMEN AND NATIONALISM IN THE MAKING OF MODERN GREECE The Founding of the Kingdom to the Greco-Turkish War Simone Bunse SMALL STATES AND EU GOVERNANCE Leadership through the Council Presidency Judith Marquand DEVELOPMENT AID IN RUSSIA Lessons from Siberia Li-Chen Sim THE RISE AND FALL OF PRIVATIZATION IN THE RUSSIAN OIL INDUSTRY Stefania Bernini FAMILY LIFE AND INDIVIDUAL WELFARE IN POSTWAR EUROPE Britain and Italy Compared Tomila V. Lankina, Anneke Hudalla and Helmut Wollman LOCAL GOVERNANCE IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE Comparing Performance in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Russia Cathy Gormley-Heenan POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE NORTHERN IRELAND PEACE PROCESS Role, Capacity and Effect Lori Plotkin Boghardt KUWAIT AMID WAR, PEACE AND REVOLUTION Paul Chaisty LEGISLATIVE POLITICS AND ECONOMIC POWER IN RUSSIA Valpy FitzGerald, Frances Stewart -

THE POLITICAL CAREER of JAMES A. FARLEY by .Eaplene Swind^Man a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT of HISTORY In

The political career of James A. Farley Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Swindeman, Earlene, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 10:23:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/317993 THE POLITICAL CAREER OF JAMES A. FARLEY by .Eaplene Swind^man A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS . In The Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknow ledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the inter ests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, per mission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: y Herman Bateman V Dkte Professor of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author expresses foremost appreciation to her advisors Dr. -

The National Miniature Gallery,” 19 September 1851 (Keywords: Daniel E

“The National Miniature Gallery,” 19 September 1851 (keywords: Daniel E. Gavit, National Miniature Gallery, 247 Broadway, history of the daguerreotype, history of photography) ————————————————————————————————————————————— THE DAGUERREOTYPE: AN ARCHIVE OF SOURCE TEXTS, GRAPHICS, AND EPHEMERA The research archive of Gary W. Ewer regarding the history of the daguerreotype http://www.daguerreotypearchive.org EWER ARCHIVE N8510030 ————————————————————————————————————————————— Published in: New-York Daily Times 1:2 (19 September 1851): n.p. (third page of issue). THE NATIONAL MINIATURE GALLERY. O. 247 BROADWAY, CORNER OF MURRAY ST., N over Ball, Tompkins & Black’s. The attention of the public is requested to this establishment, for the production of Photographs on SILVER, IVORY, GLASS and PAPER; and as proof of their superiority, the Proprietor would state that he has received the first premiums of the Ameri- can Institute, State Agricultural Society, and other Associ- ations for the encouragements of the Arts, etc. The facilities to make pictures are of the most superior kind, and each picture is done under the immediate super- vision of the Proprietor, and the utmost pains taken to make it a gem of art. The Gallery is the most extensive in the world, and con- tains the Portraits of nearly all the most eminent men of the age, of which there are nearly ten to one of any other estab- lishment in New-York. Among the collection will be found the following, and many other, too numerous to mention in an advertisement: Andrew Jackson, Gen./ Gaines, Rev. Dr. Soudder, Henry Clay, Gen. Morgan, Rev. Dr. Cook, Daniel Webster, Gen Clinch Rev. Dr. Knox, James K. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, MAY 19, 1995 No. 84 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, May 22, 1995, at 12 noon. Senate FRIDAY, MAY 19, 1995 (Legislative day of Monday, May 15, 1995) The Senate met at 8:45 a.m., on the RECOGNITION OF THE ACTING Pending: expiration of the recess, and was called MAJORITY LEADER Hutchison (for Domenici) amendment No. 1111, in the nature of a substitute. to order by the President pro tempore The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The Mrs. HUTCHISON. Mr. President, I [Mr. THURMOND]. acting majority leader is recognized. watched, as I am sure many people in SCHEDULE America did, last night and all day yes- Mrs. HUTCHISON. Mr. President, PRAYER terday, I guess starting at noon, the this morning the leader time has been two sides debating probably the most reserved and the Senate will imme- The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John important vote we will take maybe in diately resume consideration of Senate Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: our lifetime. Concurrent Resolution 13, the budget Lord of all life, Sovereign of this Na- The balanced budget amendment, I resolution. felt, was the most important vote be- tion, we ask You to bless the women Under the previous order, a rollcall cause that would set a framework for and men of this Senate as they press on vote will occur this morning at 10:45 on us, for the future generations to make to express their convictions on the the Domenici amendment, the text of sure that in our framework of Govern- soul-sized fiscal issues confronting our which is President Clinton’s budget. -

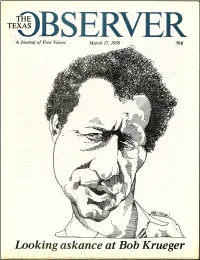

Looking Askance at Bob Krueger Focusing by Pat Black Two Cars Stop in Front of a Frame House in a Quiet West Austin Neighborhood

A Journal of Free Voices March 17, 1978 500 Looking askance at Bob Krueger Focusing By Pat Black Two cars stop in front of a frame house in a quiet West Austin neighborhood. The stillness of the hour before dawn blunts the sting of the cold weather. Four young men are met at the door by Tom Henderson, who is dressed in a bright red bathrobe. The Texas Henderson offers to make a pot of coffee, but the visitors have been wrenched out of sleep too early and are wary of OBSERVER shocking their bodies any more than necessary right now. No e The Texas Observer Publishing Co., 1978 coffee. The host pads back and forth from the kitchen to the Ronnie Dugger, Publisher spare bedroom to see if Bob Krueger will be able to face the day's outing despite a cold and less than four hours' rest. Vol. 70, No. 5 March 17, 1978 We will go. Krueger emerges and greets everyone. He and the young men about to leave with him have on jeans, cowboy Incorporating the State Observer and the East Texas Demo- boots, and heavy coats. crat, which in turn incorporated the Austin Forum-Advocate. The battered gray station wagon is loaded, and three men EDITOR Jim Hightower drive off. The two others follow in a compact. There is still no MANAGING EDITOR Lawrence Walsh sign of the rising sun. A group more typical of Texas would be ASSOCIATE EDITOR Linda Rocawich leaving on a deer hunt. But these men are off on a hunting trip EDITOR.AT LARGE Ronnie Dugger of their own–the quarry is a seat in the United States Senate. -

The Fire Last Time Worker Safety Laws After the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

The Fire Last Time Worker Safety Laws after the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire By Peter Dreier and Donald Cohen century ago, on March 25, 1911, 146 garment workers, most of them Jewish and Italian immigrant girls in their A teens and twenties, perished after a fire broke out at the Triangle Waist Company in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Even after the fire, the city’s businesses continued to insist they could regulate themselves, but the deaths clearly demonstrated that companies like Triangle, if left to their own devices, would not concern themselves with their workers’ safety. Despite this business opposition, the public’s response to the fire and to the 146 deaths led to landmark state regulations. 100 years after the Triangle fire, we still hear much banking, and telecommunication providers—asking of the same anti-regulation rhetoric that was popular them to identify “burdensome government regula - among business groups whenever reformers sought to tions” that they want eliminated. use government to get businesses to act more respon - The business groups responded with a long wish sibly and protect consumers, workers, and the envi - list, including rules to control “combustible dust” 30 ronment. For example, the disasters last year that that has resulted in explosions killing workers; rules killed 29 miners at Upper Big Branch and 11 oil rig to track musculoskeletal disorders, such as tendonitis, workers in the Gulf of Mexico could have been carpal tunnel, or back injuries, that impact millions avoided had lawmakers resisted lobbying by mine of workers at keyboards, in construction, or in meat owners and BP to weaken safety regulations. -

Commencement 1920-1940

( bi.CLJL^vOi<^ . THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIMORE Conferring of Degrees At The Close Of The Fifty-Sixth Academic Year JUNE 14, 1932 IN THE LYRIC THEATRE AT 4 P. M. MARSHALS Professor William 0. Weyforth Chief Marshal Aids Dr. W. S. Holt Dr. E. E. Franklin Dr. R. T. Abercrombie Dr. E. C. Andrus Dr. G. H. Evans Dr. W. W. Ford Mr. M. W. Pullen Dr. J. Hart USHERS J. Gaillard Fret Chief Usher Ronald A. Baker, Jr. C. Albert Kuper, Jr. Martin E. Cornman Eugene D. Lyon Charles H. Davis James G. McCabe John Henderson III Austin D. Murphy Lewis G. von Lossberg The musical program is under the direction of Philip S. Morgan and is presented by the Johns Hopkins Orchestra, John Itzel, Conductor. — — ORDER OF EXERCISES i Academic Procession " March Militaire "—F. Schubert II Invocation The Keverend Noble C. Powell, D. D. Rector of Emmanuel Church III Address The President op the University IV " Morgenstimmung " from Peer Gynt Suite E. Grieg V Conferring op Degrees Bachelors of Arts, presented by Dean Berry Bachelors of Engineering, presented by Professor Kouwenhoven Bachelors of Science in Chemistry, presented by Professor Kouwenhoven Bachelors of Science in Economics, presented by Professor Hollander Bachelors of Science, presented by Professor Bamberger Eecipients of Certificates in Public Health, presented by Dean Frost Master of Education, presented by Professor Bamberger Masters of Engineering, presented by Professor Christie Master of Science in Hygiene, presented by Dean Frost Masters of Arts, presented by Professor Miller Doctors of Education, presented by Professor Bamberger Doctors of Engineering, presented by Professor Christie Doctors of Public Health, presented by Dean Frost Doctors of Science in Hygiene, presented by Dean Frost Doctors of Medicine, presented by Dean Chesney Doctors of Philosophy, presented by Professor Miller VI Conferring of Commissions in the Officers' Keserve Corps vii Presentations Portrait of Dr.