Newsletter Volume 44, Number 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles

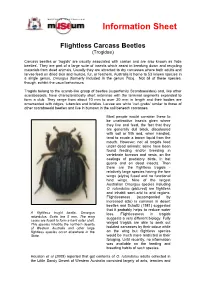

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles (Trogidae) Carcass beetles or ‘trogids’ are usually associated with carrion and are also known as ‘hide beetles’. They are part of a large suite of insects which assist in breaking down and recycling materials from dead animals. Usually they are attracted to dry carcasses where both adults and larvae feed on dried skin and muscle, fur, or feathers. Australia is home to 53 known species in a single genus, Omorgus (formerly included in the genus Trox). Not all of these species, though, exhibit the usual behaviours. Trogids belong to the scarablike group of beetles (superfamily Scarabaeoidea) and, like other scarabaeoids, have characteristically short antennae with the terminal segments expanded to form a club. They range from about 10 mm to over 30 mm in length and their bodies are ornamented with ridges, tubercles and bristles. Larvae are white ‘curlgrubs’ similar to those of other scarabaeoid beetles and live in burrows in the soil beneath carcasses. Most people would consider these to be unattractive insects given where they live and feed, the fact that they are generally dull black, discoloured with soil or filth and, when handled, tend to exude a brown liquid from the mouth. However, not all trogids feed under dead animals: some have been found feeding and/or breeding in vertebrate burrows and nests, on the castings of predatory birds, in bat guano and on dead insects. Then there are the flightless trogids relatively large species having the fore wings (elytra) fused and no functional hind wings. Nine of the largest Australian Omorgus species including O. -

Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny

insects Article Three Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Orestes guangxiensis, Peruphasma schultei, and Phryganistria guangxiensis (Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny Ke-Ke Xu 1, Qing-Ping Chen 1, Sam Pedro Galilee Ayivi 1 , Jia-Yin Guan 1, Kenneth B. Storey 2, Dan-Na Yu 1,3 and Jia-Yong Zhang 1,3,* 1 College of Chemistry and Life Science, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China; [email protected] (K.-K.X.); [email protected] (Q.-P.C.); [email protected] (S.P.G.A.); [email protected] (J.-Y.G.); [email protected] (D.-N.Y.) 2 Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada; [email protected] 3 Key Lab of Wildlife Biotechnology, Conservation and Utilization of Zhejiang Province, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Simple Summary: Twenty-seven complete mitochondrial genomes of Phasmatodea have been published in the NCBI. To shed light on the intra-ordinal and inter-ordinal relationships among Phas- matodea, more mitochondrial genomes of stick insects are used to explore mitogenome structures and clarify the disputes regarding the phylogenetic relationships among Phasmatodea. We sequence and annotate the first acquired complete mitochondrial genome from the family Pseudophasmati- dae (Peruphasma schultei), the first reported mitochondrial genome from the genus Phryganistria Citation: Xu, K.-K.; Chen, Q.-P.; Ayivi, of Phasmatidae (P. guangxiensis), and the complete mitochondrial genome of Orestes guangxiensis S.P.G.; Guan, J.-Y.; Storey, K.B.; Yu, belonging to the family Heteropterygidae. We analyze the gene composition and the structure D.-N.; Zhang, J.-Y. -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

Mitochondrial Genomes Resolve the Phylogeny of Adephaga

1 Mitochondrial genomes resolve the phylogeny 2 of Adephaga (Coleoptera) and confirm tiger 3 beetles (Cicindelidae) as an independent family 4 Alejandro López-López1,2,3 and Alfried P. Vogler1,2 5 1: Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, UK 6 2: Department of Life Sciences, Silwood Park Campus, Imperial College London, Ascot SL5 7PY, UK 7 3: Departamento de Zoología y Antropología Física, Facultad de Veterinaria, Universidad de Murcia, Campus 8 Mare Nostrum, 30100, Murcia, Spain 9 10 Corresponding author: Alejandro López-López ([email protected]) 11 12 Abstract 13 The beetle suborder Adephaga consists of several aquatic (‘Hydradephaga’) and terrestrial 14 (‘Geadephaga’) families whose relationships remain poorly known. In particular, the position 15 of Cicindelidae (tiger beetles) appears problematic, as recent studies have found them either 16 within the Hydradephaga based on mitogenomes, or together with several unlikely relatives 17 in Geadeadephaga based on 18S rRNA genes. We newly sequenced nine mitogenomes of 18 representatives of Cicindelidae and three ground beetles (Carabidae), and conducted 19 phylogenetic analyses together with 29 existing mitogenomes of Adephaga. Our results 20 support a basal split of Geadephaga and Hydradephaga, and reveal Cicindelidae, together 21 with Trachypachidae, as sister to all other Geadephaga, supporting their status as Family. We 22 show that alternative arrangements of basal adephagan relationships coincide with increased 23 rates of evolutionary change and with nucleotide compositional bias, but these confounding 24 factors were overcome by the CAT-Poisson model of PhyloBayes. The mitogenome + 18S 25 rRNA combined matrix supports the same topology only after removal of the hypervariable 26 expansion segments. -

Os Cicindelídeos (COLEOPTERA, CICINDELIDAE): TAXONOMIA, MORFOLOGIA, ONTOGENIA, ECOLOGIA E EVOLUÇÃO

Professor Germano da Fonseca Sacarrão, Museu Bocage, Lisboa, 1994, pp. 233-285. os CICINDELíDEOS (COLEOPTERA, CICINDELIDAE): TAXONOMIA, MORFOLOGIA, ONTOGENIA, ECOLOGIA E EVOLUÇÃO. por ARTUR R. M. SERRANO Departamento de Zoologia e Antropologia, Faculdade de Ciências de Lisboa, Edifício C2, 3.° piso, Campo Grande, 1700 Lisboa - Portugal. «Devemos ter sempre presente o facto de os organismos serem criaturas históricas, com um longo passado de transforma ções resultantes de complexas relações entre os seres vivos e os factores do ambiente». G.F. SACARRÃO (1965), ln «A Adaptação e a Invenção do Futuro». ABSTRACT The tiger heetles (Coleoptera, Cicindelidae); taxonomy, morphology, ontogeny, ecology and evolution The family of tiger beetles (Coleoptera, Cicindelidae) is an ideal group for studies in areas as taxonomy, morphology, ontogeny, physiology, eeology, behavior, evolution and biogeography. ln a time in which biodiversity is in great danger, we try in this work to present an update of our knowledge in the previously mentioned areas and therefore call attention to the importance of this group of inseets. To com pose ali these data more than 300 references were consulted fram several hundreds pertinent works. 234 Ar/ur R. M. Serrano RESUMO A família dos coleópteros cincidelídeos constitui um grupo ideal para estudos nas áreas de taxonomia, morfologia, ontogenia, fisiologia. ecologia. comportamento, evolução e biogeografia. Numa altura em que a biodiversidade se encontra em grande perigo, tentamos neste artigo apresentar os conhecimentos mais recentes naquelas áreas, chamando portanto a atenção para a importância deste grupo de insectos. Para a elaboração destes dados foram consultadas mais de 300 obras sobre o assunto. INTRODUÇÃO Desde os tempos de Lineu que foram publicados numerosos trabalhos sobre taxonomia, ou pequenas notas e estudos sobre comportamento, zoogeografia, anatomia, biologia, etc. -

Distribution and Feeding Behavior of Omorgus Suberosus (Coleoptera: Trogidae) in Lepidochelys Olivacea Turtle Nests

RESEARCH ARTICLE Distribution and Feeding Behavior of Omorgus suberosus (Coleoptera: Trogidae) in Lepidochelys olivacea Turtle Nests Martha L. Baena1, Federico Escobar2*, Gonzalo Halffter2, Juan H. García–Chávez3 1 Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Veracruzana (IIB–UV), Xalapa, Veracruz, México, 2 Instituto de Ecología, A. C., Red de Ecoetología, Xalapa, Veracruz, México, 3 Laboratorio de Ecología de Poblaciones, Escuela de Biología, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, México * [email protected] Abstract Omorgus suberosus (Fabricius, 1775) has been identified as a potential predator of the eggs of the turtle Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz, 1829) on one of the main turtle nesting beaches in the world, La Escobilla in Oaxaca, Mexico. This study presents an analysis of the – OPEN ACCESS spatio temporal distribution of the beetle on this beach (in areas of high and low density of L. olivacea nests over two arrival seasons) and an evaluation, under laboratory conditions, of Citation: Baena ML, Escobar F, Halffter G, García– Chávez JH (2015) Distribution and Feeding Behavior the probability of damage to the turtle eggs by this beetle. O. suberosus adults and larvae of Omorgus suberosus (Coleoptera: Trogidae) in exhibited an aggregated pattern at both turtle nest densities; however, aggregation was Lepidochelys olivacea Turtle Nests. PLoS ONE 10(9): greater in areas of low nest density, where we found the highest proportion of damaged eggs. e0139538. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139538 Also, there were fluctuations in the temporal distribution of the adult beetles following the arrival Editor: Jodie L. Rummer, James Cook University, of the turtles on the beach. Under laboratory conditions, the beetles quickly damaged both AUSTRALIA dead eggs and a mixture of live and dead eggs, but were found to consume live eggs more Received: November 20, 2014 slowly. -

INSECTS of MICRONESIA Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae

INSECTS OF MICRONESIA Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae By o. L. CARTWRIGHT EMERITUS ENTOMOLOGIST, DEPARTMENT OF ENTOMOLOGY, UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY AND R. D. GORDON SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY LABORATORY, ENTOMOLOGY Research Division. ARS. USDA INTRODUCTION The Scarabaeidae, one of the larger and better known families of beetles has world-wide distribution. The group has penetrated in surpris ing numbers even the remote islands of the Pacific Ocean. How this has been accomplished can only be surmised but undoubtedly many have managed to accompany man in his travels, with his food and domestic animals, accidental ly hidden in whatever he carried with him or in his means of conveyance. Commerce later greatly increased such possible means. Others may have been carried by ocean currents or winds in floating debris of various kinds. Although comparatively few life cycles have been completely studied, their very diverse habits increase the chances of survival of at least some members of the group. The food habits of the adults range from the leaf feeding Melolonthinae to the coprophagous Scarabaeinae and scavenging Troginae. Most of the larvae or grubs find their food in the soil. Many species have become important as economic pests, the coconut rhinoceros beetle, Oryctes rhinoceros (Linn.) being a Micronesian example. This account of the Micronesian Scarabaeidae, as part of die Survey of Micronesian Insects, has been made possible by the support provided by the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, the Pacific Science Board, the National Science Foundation, the United States office of Naval Research and the National Academy of Sciences. The material upon which this report is based was assembled in the United States National Museum of Natural History from existing collections and survey collected specimens. -

Sovraccoperta Fauna Inglese Giusta, Page 1 @ Normalize

Comitato Scientifico per la Fauna d’Italia CHECKLIST AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ITALIAN FAUNA FAUNA THE ITALIAN AND DISTRIBUTION OF CHECKLIST 10,000 terrestrial and inland water species and inland water 10,000 terrestrial CHECKLIST AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ITALIAN FAUNA 10,000 terrestrial and inland water species ISBNISBN 88-89230-09-688-89230- 09- 6 Ministero dell’Ambiente 9 778888988889 230091230091 e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare CH © Copyright 2006 - Comune di Verona ISSN 0392-0097 ISBN 88-89230-09-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers and of the Authors. Direttore Responsabile Alessandra Aspes CHECKLIST AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ITALIAN FAUNA 10,000 terrestrial and inland water species Memorie del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona - 2. Serie Sezione Scienze della Vita 17 - 2006 PROMOTING AGENCIES Italian Ministry for Environment and Territory and Sea, Nature Protection Directorate Civic Museum of Natural History of Verona Scientifi c Committee for the Fauna of Italy Calabria University, Department of Ecology EDITORIAL BOARD Aldo Cosentino Alessandro La Posta Augusto Vigna Taglianti Alessandra Aspes Leonardo Latella SCIENTIFIC BOARD Marco Bologna Pietro Brandmayr Eugenio Dupré Alessandro La Posta Leonardo Latella Alessandro Minelli Sandro Ruffo Fabio Stoch Augusto Vigna Taglianti Marzio Zapparoli EDITORS Sandro Ruffo Fabio Stoch DESIGN Riccardo Ricci LAYOUT Riccardo Ricci Zeno Guarienti EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Elisa Giacometti TRANSLATORS Maria Cristina Bruno (1-72, 239-307) Daniel Whitmore (73-238) VOLUME CITATION: Ruffo S., Stoch F. -

VKM Rapportmal

VKM Report 2016: 36 Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety Report from the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) 2016: Assessment of risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety 29.06.2016 ISBN: 978-82-8259-226-0 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) Po 4404 Nydalen N – 0403 Oslo Norway Phone: +47 21 62 28 00 Email: [email protected] www.vkm.no www.english.vkm.no Suggested citation: VKM (2016). Assessment of risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects. Scientific Opinion on the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety, ISBN: 978-82-8259-226-0, Oslo, Norway VKM Report 2016: 36 Assessment of risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of terrestrial arachnids and insects Authors preparing the draft opinion Anders Nielsen (chair), Merethe Aasmo Finne (VKM staff), Maria Asmyhr (VKM staff), Jan Ove Gjershaug, Lawrence R. Kirkendall, Vigdis Vandvik, Gaute Velle (Authors in alphabetical order after chair of the working group) Assessed and approved The opinion has been assessed and approved by Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Members of the panel are: Vigdis Vandvik (chair), Hugo de Boer, Jan Ove Gjershaug, Kjetil Hindar, Lawrence R. -

Tigers in Texas

Tigers in Texas Ross Winton Texas Master Naturalist Annual Meeting Invertebrate Biologist Rockwall, Texas Nongame & Rare Species Program October 18-20, 2019 Texas Parks & Wildlife Photo: Denver Museum of Nature & Science / Chris Grinter Tigers in Texas Texas Parks and Wildlife Mission To manage and conserve the natural and cultural resources of Texas and to provide hunting, fishing and outdoor recreation opportunities for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. Nongame & Rare Species Program The Nongame and Rare Species Programs focus is Texas' rich diversity of nongame animals, plants, and natural communities. Our biologists collect, evaluate, and synthesize significant amounts of data to better inform conservation decisions and formulate management practices. By taking a proactive approach, we work to prevent the need for future threatened and endangered species listings and to recover listed species. Photo: Alliance Texas for America’sWildlife &Fish Tigers in Texas Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae Predatory Ground Beetles Sight predators Larvae burrow and wait for prey Identification: Sickle-shaped mandibles with teeth 11-segmented antennae Eyes and head wider than the abdomen Long thin legs Tunnel-building behavior of larvae Very charismatic group that gains a great deal of attention from collectors Photo: Denver Museum of Nature & Science / Chris Grinter Tigers in Texas Collecting Methods: Net Pitfall Trap Debris Flipping Extraction from nightly burrows “Fishing” Observation Methods: Naked Eye Binoculars Digi-scoping -

Larval Systematics of the Troginae in North America, with Notes On

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF CHARLES WILLIAM BAKER for the Ph. D. in Entomology (Name) (Degree) (Major) Date thesis is presented 4ila-as t` :;2,/9c, Title LARVAL SYSTEMATICS OF THE TROGINAE IN NORTH AMERICA WITH NOTES ON BIOLOGIES AND LIFE HISTORIES (COLEOPTERA: SCARABAEIDAE). Abstract approve Major professor A study of the immature stages of the subfamily Troginae in North America was conducted from the spring of 1963 through the spring of 1965, Larvae of Trox and Omorgus were easily reared in the laboratory, but all attempts to rear the larvae of Glaresis were unsuccessful, The suberosus group, one of the five groups of species within the genus Trox in North America as recognized by Vaurie (1955), is given generic status. The 17 species of the suberosus group are placed in the genus Omorgus which was originally proposed by Erichson (1847) with Trox suberosus later designated as the type. The placement of these 17 species in Omorgus is done on the basis of the larval morphology and recent work on the morphology and cyto- genetics of the adults. A table listing 17 characters by which the genus Trox may be distinguished from the genus Omorgus is pre- sented. The other four groups of species in North America, as recognized by Vaurie (1955), are retained in the genus Trox. The adults of 22 species of Trox and Omorgus were collected during the summers of 1963, 1964, and 1965, in the states of Oregon, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Cultures of these beetles were established in the laboratory and 595 larvae were reared for the systematic studies of the immature stages. -

Ecological Sustainability Analysis of the Kaibab National Forest

Ecological Sustainability Analysis of the Kaibab National Forest: Species Diversity Report Version 1.2.5 Including edits responding to comments on version 1.2 Prepared by: Mikele Painter and Valerie Stein Foster Kaibab National Forest For: Kaibab National Forest Plan Revision Analysis 29 June 2008 SDR version 1.2.5 29 June 2008 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. i Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 PART I: Species Diversity .............................................................................................................. 1 Species Diversity Database and Forest Planning Species........................................................... 1 Criteria .................................................................................................................................... 2 Assessment Sources ................................................................................................................ 3 Screening Results .................................................................................................................... 4 Habitat Associations and Initial Species Groups ........................................................................ 8 Species associated with ecosystem diversity characteristics of terrestrial vegetation or aquatic systems ......................................................................................................................