Marine Turtle Newsletter Issue Number 162 January 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles

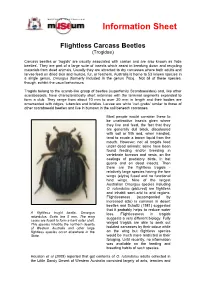

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles (Trogidae) Carcass beetles or ‘trogids’ are usually associated with carrion and are also known as ‘hide beetles’. They are part of a large suite of insects which assist in breaking down and recycling materials from dead animals. Usually they are attracted to dry carcasses where both adults and larvae feed on dried skin and muscle, fur, or feathers. Australia is home to 53 known species in a single genus, Omorgus (formerly included in the genus Trox). Not all of these species, though, exhibit the usual behaviours. Trogids belong to the scarablike group of beetles (superfamily Scarabaeoidea) and, like other scarabaeoids, have characteristically short antennae with the terminal segments expanded to form a club. They range from about 10 mm to over 30 mm in length and their bodies are ornamented with ridges, tubercles and bristles. Larvae are white ‘curlgrubs’ similar to those of other scarabaeoid beetles and live in burrows in the soil beneath carcasses. Most people would consider these to be unattractive insects given where they live and feed, the fact that they are generally dull black, discoloured with soil or filth and, when handled, tend to exude a brown liquid from the mouth. However, not all trogids feed under dead animals: some have been found feeding and/or breeding in vertebrate burrows and nests, on the castings of predatory birds, in bat guano and on dead insects. Then there are the flightless trogids relatively large species having the fore wings (elytra) fused and no functional hind wings. Nine of the largest Australian Omorgus species including O. -

Beach Dynamics and Impact of Armouring on Olive Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys Olivacea) Nesting at Gahirmatha Rookery of Odisha Coast, India

Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences Vol. 45(2), February 2016, pp. 233-238 Beach dynamics and impact of armouring on olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) nesting at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast, India Satyaranjan Behera1, 2, Basudev Tripathy3*, K. Sivakumar2, B.C. Choudhury2 1Odisha Biodiversity Board, Regional Plant Resource Centre Campus, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar-15 2Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, PO Box 18, Chandrabani, Dehradun – 248 001, India. 3Zoological Survey of India, Prani Vigyan Bhawan, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 (India) *[E. mail:[email protected]] Received 28 March 2014; revised 18 September 2014 Gahirmatha arribada beach are most dynamic and eroding at a faster rate over the years from 2008-09 to 2010-11, especially during the turtles breeding seasons. Impact of armouring cement tetrapod on olive ridley sea turtle nesting beach at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast has also been reported in this study. This study documented the area of nesting beach has reduced from 0.07 km2to 0.06 km2. Due to a constraint of nesting space, turtles were forced to nest in the gap of cement tetrapods adjacent to the arribada beach and get entangled there, resulting into either injury or death. A total of 209 and 24 turtles were reported to be injured and dead due to placement of cement tetrapods in their nesting beach during 2008-09 and 2010-11 respectively. Olive ridley turtles in Odisha are now exposed to many problems other than fishing related casualty and precautionary measures need to be taken by the wildlife and forest authorities to safeguard the Olive ridleys and their nesting habitat at Gahirmatha. -

A New Xinjiangchelyid Turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the Evolution of the Basipterygoid Process in Mesozoic Turtles Rabi Et Al

A new xinjiangchelyid turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the evolution of the basipterygoid process in Mesozoic turtles Rabi et al. Rabi et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:203 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/203 Rabi et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:203 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/203 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access A new xinjiangchelyid turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the evolution of the basipterygoid process in Mesozoic turtles Márton Rabi1,2*, Chang-Fu Zhou3, Oliver Wings4, Sun Ge3 and Walter G Joyce1,5 Abstract Background: Most turtles from the Middle and Late Jurassic of Asia are referred to the newly defined clade Xinjiangchelyidae, a group of mostly shell-based, generalized, small to mid-sized aquatic froms that are widely considered to represent the stem lineage of Cryptodira. Xinjiangchelyids provide us with great insights into the plesiomorphic anatomy of crown-cryptodires, the most diverse group of living turtles, and they are particularly relevant for understanding the origin and early divergence of the primary clades of extant turtles. Results: Exceptionally complete new xinjiangchelyid material from the ?Qigu Formation of the Turpan Basin (Xinjiang Autonomous Province, China) provides new insights into the anatomy of this group and is assigned to Xinjiangchelys wusu n. sp. A phylogenetic analysis places Xinjiangchelys wusu n. sp. in a monophyletic polytomy with other xinjiangchelyids, including Xinjiangchelys junggarensis, X. radiplicatoides, X. levensis and X. latiens. However, the analysis supports the unorthodox, though tentative placement of xinjiangchelyids and sinemydids outside of crown-group Testudines. A particularly interesting new observation is that the skull of this xinjiangchelyid retains such primitive features as a reduced interpterygoid vacuity and basipterygoid processes. -

GHOST GEAR: the ABANDONED FISHING NETS HAUNTING OUR OCEANS Sea Turtle Entangled in Fishing Gear in the Mediterranean Sea © Marco Care/Greenpeace CONTENTS

GHOST GEAR: THE ABANDONED FISHING NETS HAUNTING OUR OCEANS Sea turtle entangled in fishing gear in the Mediterranean Sea © Marco Care/Greenpeace CONTENTS 4 Zusammenfassung 5 Executive summary 6 Introduction 8 Main types of fishing – Nets – Lines – Traps & pots – FADs 11 Ghost gear impacts – Killing ocean creatures – Damaging habitats – Economic and other impacts 13 Current regulations – International agreements and recommendations – Other programmes and resolutions – A cross-sector approach – The need for a Global Ocean Treaty 16 References 2019 / 10 Published by Greenpeace Germany November 2019 Stand Greenpeace e. V., Hongkongstraße 10, 20457 Hamburg, Tel. 040/3 06 18 - 0, [email protected] , www . greenpeace . de Authors Karli Thomas, Dr. Cat Dorey and Farah Obaidullah Responsible for content Helena Spiritus Layout Klasse 3b, Hamburg S 0264 1 Contents 3 DEUTSCHE ZUSAMMENFASSUNG DER STUDIE GHOST GEAR: THE ABANDONED FISHING NETS HAUNTING OUR OCEANS → Rund 640.000 Tonnen altes Fischereigerät inklusive Geisternetzen, Bojen, Leinen, Fallen und Körbe landen jährlich als Fischereimüll in den Ozeanen. → Weltweit trägt altes Fischereigerät zu etwa zehn Prozent zum Plastikeintrag in die Meere bei. → 45 Prozent aller Arten auf der Roten IUCN-Liste hatten bereits Kontakt mit Plastik im Meer. → Sechs Prozent aller eingesetzten Netze, neun Prozent aller Fallen und 29 Prozent aller Langleinen gehen jährlich auf den Ozeanen verloren und enden als Meeresmüll. → Treibnetze, Fallen und Fischsammler (Fish Aggregating Devices, FADs) gehen weltweit am häufigsten als Müll auf den Ozeanen verloren und bergen die meisten Risiken für Meereslebewesen. → Durch FADs sterben 2,8 bis 6,7 Mal mehr Tiere - darunter bedrohte Arten wie Haie – als Beifang als die Zielarten, für die sie eingesetzt werden. -

The Evolutionary Significance of Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination in Reptiles

Rollins Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 2 Article 5 Issue 1 RURJ Spring 2010 4-1-2007 The volutE ionary Significance of Temperature- Dependent Sex Determination in Reptiles Cavia Teller Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/rurj Recommended Citation Teller, Cavia (2010) "The vE olutionary Significance of Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination in Reptiles," Rollins Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/rurj/vol2/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rollins Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Teller: Sex Determination in Reptiles The evolutionary significance of temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles Cayla Teller Rollins College Department of Biology 1000 Holt Avenue Winter Park, FL 32789 May 23, 2007 Published by Rollins Scholarship Online, 2010 1 Rollins Undergraduate Research Journal, Vol. 2 [2010], Iss. 1, Art. 5 2 Table of Contents: Page I. Abstract 3 II. Introduction 4 III. Sex-Determining Mechanisms 5 IV. Patterns within Sex-Determination 7 V. Gonad Differentiation 10 VI. Aromatase Influence and Importance 11 VII. Estrogen and Steroid Effects 13 VIII. Sex-Ratio and Selection Effects 16 IX. Effect of Maternal Nest-Site Choice on Sex-Determination 19 X. TSD and Global Warming 21 XI. Conclusion of Evolutionary Significance 22 XII. Acknowledgements 23 XIII. Literature Cited 23 http://scholarship.rollins.edu/rurj/vol2/iss1/5 2 Teller: Sex Determination in Reptiles 3 I. -

Ghost Net Impacts on Coral Reefs Time to Complete Lesson: 20-30 Minutes

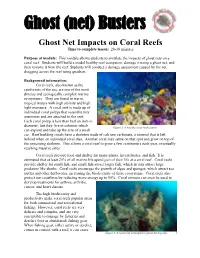

Ghost (net) Busters Ghost Net Impacts on Coral Reefs Time to complete lesson: 20-30 minutes Purpose of module: This module allows students to simulate the impacts of ghost nets on a coral reef. Students will build a model healthy reef ecosystem, damage it using a ghost net, and then remove it from the reef. Students will conduct a damage assessment caused by the net dragging across the reef using quadrats. Background information: Coral reefs, also known as the rainforests of the sea, are one of the most diverse and ecologically complex marine ecosystems. They are found in warm, tropical waters with high salinity and high light exposure. A coral reef is made up of individual coral polyps that resemble tiny anemones and are attached to the reef. Each coral polyp is less than half an inch in diameter, but they live in colonies which Figure 1: A healthy coral reef system. can expand and take up the size of a small car. Reef building corals have a skeleton made of calcium carbonate, a mineral that is left behind when an individual coral dies. Another coral may settle on that spot and grow on top of the remaining skeleton. This allows a coral reef to grow a few centimeters each year, eventually reaching massive sizes. Coral reefs provide food and shelter for many plants, invertebrates, and fish. It is estimated that at least 25% of all marine life spendCredit: part MostBeautifulThings.net of their life at a coral reef. Coral reefs provide shelter for small fish, and small fish attract larger fish, which in turn attract large predators like sharks. -

Sea Turtle Stranding Response & Rescue 2019 Summary of Results

Sea Turtle Stranding Response & Rescue 2019 Summary of Results, Maui, Hawaiʻi Tommy Cutt, Jennifer Martin MOC Marine Institute 192 Maʻalaea Rd. Wailuku, Hawaiʻi 96793 www.mocmarineinstitute.org 2019 Stranding Summary Maui, Hawaiʻi Contents Background.........................................................................................................................................................3 Team....................................................................................................................................................................4 Partners & Collaborators.....................................................................................................................................4 Sea Turtle Stranding Data...................................................................................................................................5 Map: Stranding Type by Location......................................................................................................................8 Fishing Gear......................................................................................................................................................11 Map: Heat Map of Fishery Interactions............................................................................................................12 Fishing Line Recycling Program......................................................................................................................13 Map: Fishing Line Recycling Bin Locations....................................................................................................14 -

In the Northern Mariana Islands

THE TRADITIONAL AND CEREMONIAL USE OF THE GREEN TURTLE (Chelonia mydas) IN THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS with recommendations for ITS USE IN CULTURAL EVENTS AND EDUCATION A Report prepared for the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council and the University of Hawaii Sea Grant College Program by Mike A. McCoy Kailua-Kona, Hawaii December, 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................4 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................8 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................9 1.1 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................9 1.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND METHODOLOGY ............................................................................10 1.3 DISCUSSION OF DEFINITIONS .........................................................................................................11 2. GREEN TURTLES, ISLANDS AND PEOPLE OF THE NORTHERN MARIANAS ...................12 2.1 SUMMARY OF GREEN TURTLE BIOLOGY.....................................................................................12 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS ............................................................14 2.3 SOME RELEVANT -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

Sea Turtles in the East Pacific Ocean Region

Sea Turtles in the East Pacific Ocean Region IUCN-SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group Annual Regional Report 2019 Editors Juan M. Rguez-Baron, Shaleyla Kelez, Michael Liles, Alan Zavala-Norzagaray, Olga L. Torres-Suárez, Diego F. Amorocho, Alexander R. Gaos Photo: Olive ridley (RMU LO-EPO) at Ostional, Costa Rica Photo credit: Roderic Mast Recommended citation for this report: Rguez-Baron J.M., Kelez S., Lilies M., Zavala-Norzagaray A., Torres-Suárez O.L., Amorocho D., Gaos A. (Eds.) (2019). Sea Turtles in the East Pacific Region: MTSG Annual Regional Report 2019. Draft Report of the IUCN-SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group, 2019. Recommended citation for a chapter of this report: AUTHORS (2019). CHAPTER-TITLE. In: Rguez-Baron J.M., Kelez S., Lilies M., Zavala- Norzagaray A., Torres-Suárez O.L., Amorocho D., Gaos A. R. (Eds.). Sea Turtles in the East Pacific Region: MTSG Annual Regional Report 2019. Draft Report of the IUCN- SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group, 2019. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS REGIONAL OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................ 7 1. RMU Dermochelys coriacea (DC-EPO) ....................................................................................... 8 1.1. Distribution, abundance, trends ........................................................................................................... 8 1.2. Other biological data ............................................................................................................................. 8 1.3. -

Glossidiella Peruensis Sp. Nov., a New Digenean (Plagiorchiida

ZOOLOGIA 37: e38837 ISSN 1984-4689 (online) zoologia.pensoft.net RESEARCH ARTICLE Glossidiella peruensis sp. nov., a new digenean (Plagiorchiida: Plagiorchiidae) from the lung of the brown ground snake Atractus major (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) from Peru Eva Huancachoque 1, Gloria Sáez 1, Celso Luis Cruces 1,2, Carlos Mendoza 3, José Luis Luque 4, Jhon Darly Chero 1,5 1Laboratorio de Parasitología General y Especializada, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Matemática, Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal. 15007 El Agustino, Lima, Peru. 2Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Veterinárias, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro. Rodovia BR 465, km 7, 23890-000 Seropédica, RJ, Brazil. 3Escuela de Ingeniería Ambiental, Facultad de Ingeniería y Arquitecturas, Universidad Alas Peruanas. 22202 Tarapoto, San Martín, Peru. 4Departamento de Parasitologia Animal, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro. Caixa postal 74540, 23851-970 Seropédica, RJ, Brazil. 5Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro. Rodovia BR 465, km 7, 23890-000 Seropédica, RJ, Brazil. Corresponding author: Jhon Darly Chero ([email protected]) http://zoobank.org/30446954-FD17-41D3-848A-1038040E2194 ABSTRACT. During a survey of helminth parasites of the brown ground snake, Atractus major Boulenger, 1894 (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) from Moyobamba, region of San Martin (northeastern Peru), a new species of Glossidiella Travassos, 1927 (Plagiorchiida: Plagiorchiidae) was found and is described herein based on morphological and ultrastructural data. The digeneans found in the lung were measured and drawings were made with a drawing tube. The ultrastructure was studied using scanning electron microscope. Glossidiella peruensis sp. nov. is easily distinguished from the type- and only species of the genus, Glossidiella ornata Travassos, 1927, by having an oblong cirrus sac (claviform in G. -

Helminth Parasites (Trematoda, Cestoda, Nematoda, Acanthocephala) of Herpetofauna from Southeastern Oklahoma: New Host and Geographic Records

125 Helminth Parasites (Trematoda, Cestoda, Nematoda, Acanthocephala) of Herpetofauna from Southeastern Oklahoma: New Host and Geographic Records Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 Charles R. Bursey Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University-Shenango, Sharon, PA 16146 Matthew B. Connior Life Sciences, Northwest Arkansas Community College, Bentonville, AR 72712 Abstract: Between May 2013 and September 2015, two amphibian and eight reptilian species/ subspecies were collected from Atoka (n = 1) and McCurtain (n = 31) counties, Oklahoma, and examined for helminth parasites. Twelve helminths, including a monogenean, six digeneans, a cestode, three nematodes and two acanthocephalans was found to be infecting these hosts. We document nine new host and three new distributional records for these helminths. Although we provide new records, additional surveys are needed for some of the 257 species of amphibians and reptiles of the state, particularly those in the western and panhandle regions who remain to be examined for helminths. ©2015 Oklahoma Academy of Science Introduction Methods In the last two decades, several papers from Between May 2013 and September 2015, our laboratories have appeared in the literature 11 Sequoyah slimy salamander (Plethodon that has helped increase our knowledge of sequoyah), nine Blanchard’s cricket frog the helminth parasites of Oklahoma’s diverse (Acris blanchardii), two eastern cooter herpetofauna (McAllister and Bursey 2004, (Pseudemys concinna concinna), two common 2007, 2012; McAllister et al. 1995, 2002, snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina), two 2005, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014a, b, c; Bonett Mississippi mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum et al. 2011). However, there still remains a hippocrepis), two western cottonmouth lack of information on helminths of some of (Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma), one the 257 species of amphibians and reptiles southern black racer (Coluber constrictor of the state (Sievert and Sievert 2011).