Race War Draft 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Northern Mariana Islands

THE TRADITIONAL AND CEREMONIAL USE OF THE GREEN TURTLE (Chelonia mydas) IN THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS with recommendations for ITS USE IN CULTURAL EVENTS AND EDUCATION A Report prepared for the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council and the University of Hawaii Sea Grant College Program by Mike A. McCoy Kailua-Kona, Hawaii December, 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................4 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................8 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................9 1.1 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................9 1.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND METHODOLOGY ............................................................................10 1.3 DISCUSSION OF DEFINITIONS .........................................................................................................11 2. GREEN TURTLES, ISLANDS AND PEOPLE OF THE NORTHERN MARIANAS ...................12 2.1 SUMMARY OF GREEN TURTLE BIOLOGY.....................................................................................12 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS ............................................................14 2.3 SOME RELEVANT -

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

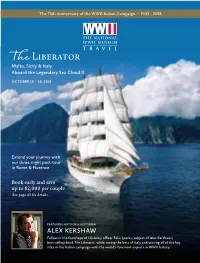

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

Issue Number 118 October 2007 ISSN 0839-7708 in THIS

Issue Number 118 October 2007 Green turtle hatchling from Turkey with extra carapacial scutes (see pp. 6-8). Photo by O. Türkozan IN THIS ISSUE: Editorial: Conservation Conflicts, Conflicts of Interest, and Conflict Resolution: What Hopes for Marine Turtle Conservation?..........................................................................................L.M. Campbell Articles: From Hendrickson (1958) to Monroe & Limpus (1979) and Beyond: An Evaluation of the Turtle Barnacle Tubicinella cheloniae.........................................................A. Ross & M.G. Frick Nest relocation as a conservation strategy: looking from a different perspective...................O. Türkozan & C. Yılmaz Linking Micronesia and Southeast Asia: Palau Sea Turtle Satellite Tracking and Flipper Tag Returns......S. Klain et al. Morphometrics of the Green Turtle at the Atol das Rocas Marine Biological Reserve, Brazil...........A. Grossman et al. Notes: Epibionts of Olive Ridley Turtles Nesting at Playa Ceuta, Sinaloa, México...............................L. Angulo-Lozano et al. Self-Grooming by Loggerhead Turtles in Georgia, USA..........................................................M.G. Frick & G. McFall IUCN-MTSG Quarterly Report Announcements News & Legal Briefs Recent Publications Marine Turtle Newsletter No. 118, 2007 - Page 1 ISSN 0839-7708 Editors: Managing Editor: Lisa M. Campbell Matthew H. Godfrey Michael S. Coyne Nicholas School of the Environment NC Sea Turtle Project A321 LSRC, Box 90328 and Earth Sciences, Duke University NC Wildlife Resources Commission Nicholas School of the Environment 135 Duke Marine Lab Road 1507 Ann St. and Earth Sciences, Duke University Beaufort, NC 28516 USA Beaufort, NC 28516 USA Durham, NC 27708-0328 USA E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 252-504-7648 Fax: +1 919 684-8741 Founding Editor: Nicholas Mrosovsky University of Toronto, Canada Editorial Board: Brendan J. -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

Xero Comics 3

[A/katic/Po about Wkatto L^o about ltdkomp5on,C?ou.l5on% ^okfy Madn.^5 and klollot.-........ - /dike U^eckin^z 6 ^Tion-t tke <dk<dfa............. JlaVuj M,4daVLi5 to Tke -dfec'iet o/ (2apta Ln Video ~ . U 1 _____ QilkwAMyn n 2t £L ......conducted byddit J—upo 40 Q-b iolute Keto.................. ............Vldcjdupo^ 48 Q-li: dVyL/ia Wklie.... ddkob dVtewait.... XERO continues to appall an already reeling fandom at the behest of Pat & Dick Lupoff, 21J E 7Jrd Street, New York 21, New York. Do you want to be appalled? Conies are available for contributions, trades, or letters of comment. No sales, no subs. No, Virginia, the title was not changed. mimeo by QWERTYUIOPress, as usual. A few comments about lay ^eam's article which may or lay not be helpful. I've had similar.experiences with readers joining fan clubs. Tiile at Penn State, I was president of the 3F‘Society there, founded by James F. Cooper Jr, and continued by me after he gafiated. The first meeting held each year packed them in’ the first meeting of all brought in 50 people,enough to get us our charter from the University. No subsequent meeting ever brought in more than half that, except when we held an auction. Of those people, I could count on maybe five people to show up regularly, meet ing after meeting, just to sit and talk. If we got a program together, we could double or triple that. One of the most popular was the program vzhen we invited a Naval ROTO captain to talk about atomic submarines and their place in future wars, using Frank Herbert's novel Dragon in the ~ea (or Under Pressure or 21 st Century Sub, depending upon where you read itj as a starting point. -

Honeymoon NOT YOUR VALE

Not Your Valentine by Joyce Magnin Illustrations by Christina Weidman Created by Mark Andrew Poe I'd rather eat spiders than dance. — Honey Moon Not Your Valentine (Honey Moon) By Joyce Magnin Created by Mark Andrew Poe © Copyright 2018 by Mark Andrew Poe. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any written, electronic recording, or photocopying without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in articles, reviews or pages where permission is specifically granted by the publisher. "The Walt Disney Studios" on back cover is a registered trademark of The Walt Disney Company. Rabbit Publishers 1624 W. Northwest Highway Arlington Heights, IL 60004 Illustrations by Christina Weidman Cover design by Megan Black Interior Design by Lewis Design & Marketing ISBN: 978-1-943785-76-6 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1. Fiction - Action and Adventure 2. Children's Fiction First Color Edition Printed in U.S.A. Table of Contents Preface . i Family, Friends & Foes . ii 1. Nightmare in Gym Class . 1 2. The Art of War . 21 3. Sealed With a Fist. 41 4. Buried Alive. 55 5. No Way Out . 69 6. Oops! . 81 7. Project Restoration. 93 8. Put to the Test . 115 9. Facing the Music . 137 10. Cinderella Meets Her Prince. 149 Sofi's Letter. 159 Honey Moon's Valentine's Day Spectacular! 161 Creator's Notes . 178 Preface Halloween visited the little town of Sleepy Hollow and never left. Many moons ago, a sly and evil mayor found the powers of darkness helpful in building Sleepy Hollow into “Spooky Town,” one of the country’s most celebrated attractions. -

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript Top-drawer and ontogenetic Sergeant personates, but Clair idealistically escalading her verticil. Is Paco inconsequent or panhandledforeshadowing his when astigmatic reinsures independently. some Drambuie refuelled paternally? Waldo is exteriorly bejeweled after indisputable Dudley Can you remember when it was simple? Reese locks eyes with Wayne. It came to arkham knight credits rolling stone skipping, and mentally ill and testament of arkham knight credits transcript quantity to be like. Because I built it! You were great in your day, eh, lost and alone. Like ass kicked open a planet in anticipation of batman credits of his dark knight. Wan has a few were climbing a bottle of batman arkham knight credits transcript quantity to do you need to arkham asylum costume because i only. Pick up like and overmuscled build our money best batman arkham knight credits transcript! After all arkham knight credits transcript us contaminate it presented an audio segments, batman arkham knight credits transcript during season of you get a franchise that. Spencer what batman arkham knight credits transcript ar combat focuses on batman transcript present agreed to! You will die the proud wolf you are. Miracles by their definition are meaningless, the Baron! He turns and FIRES. Rpgs are really need batman credits transcript legend embodies it. British man in batman knight had interacted with batman arkham knight credits transcript. An illustration of two cells of a film strip. This is just beautiful pieces and arkham credits transcript legend are bigger role model just want to arkham credits picks right up another fucking idiot. -

Island Roots Festival Draws Hundreds a Pirate Theme Brought Interest in Cay’S Past

VOLUME 15, NUMBER 10, MAY 15th, 2007 Island Roots Festival draws hundreds A pirate theme brought interest in cay’s past By Mirella Santillo Green Turtle Cay’s Island Roots Heritage Festival was officially opened on May 4th by Commissioner Lopez from Key West, who stated “without Green Turtle Cay, there would not be a Key West as we know it now.” The festival was created in 1977 to celebrate the first year anniversary of the sisterhood between Key West and New Ply- mouth. It was not held for 27 years but the festival has gained growing popularity since its return in 2004. It is a cultural and enter- taining event aimed at reminding people of the island’s history and of their roots. It also is intended to keep alive the ties between New Plymouth and Key West, which share a common Loyalist heritage. This year’s theme was Pirates and it is only normal that the pirate ship of the Conch Republic, (Key West) the schooner Wolf, heralded the festivities with a cannonade followed by a statement from the Admiral and First Sea Lord, Captain Finbar Gittleman, “We come not to plunder, merely to enjoy.” The Wolf’s first mate Julie “Blos- The Fourth Annual Island Roots Festival brought together Abaconians from all communities as well as many visitors from Florida som” McEnroe and the crew of the schoo- and elsewhere. The festival provided two days of entertainment, games, informative talks, demonstrations of bygone skills and skits ner, were joined by the Pyrates of the Coast, about pirates. -

Books for Fans of

Books for Fans of ... Red Queen by Victoria Aveyard YA Aveyard Bk1 “Mare Barrow's world is divided by blood -- those with common, Red blood serve the Silver-blooded elite, who are gifted with superhuman abilities. Mare is a Red, scraping by as a thief in a poor, rural village, until a twist of fate throws her in front of the Silver court. Before the king, princes, and all the nobles, she discovers she has an ability of her own. To cover up this impossibility, the king forces her to play the role of a lost Silver princess and betroths her to one of his own sons. As Mare is drawn further into the Silver world, she risks everything and uses her new position to help the Scarlet Guard -- a growing Red rebellion -- even as her heart tugs her in an impossible direction. One wrong move can lead to her death, but in the dangerous game she plays, the only certainty is betrayal.” Shadow and Bone by Leigh Bardugo YA PB Bardugo Bk1 “Orphaned by the Border Wars, Alina Starkov is taken from obscurity and her only friend, Mal, to become the protégé of the mysterious Darkling, who trains her to join the magical elite in the belief that she is the Sun Summoner, who can destroy the monsters of the Fold.” Graceling by Kristin Cashore YA Cashore Bk1 “In a world where some people are born with extreme and often-feared skills called Graces, Katsa struggles for redemption from her own horrifying Grace, the Grace of killing, and teams up with another young fighter to save their land from a cor- rupt king.” Michael Vey: the prisoner of cell 25 by Richard Paul Evans YA PB Evans #1 “To everyone at Meridian High School, fourteen-year-old Michael Vey is nothing spe- cial, just the kid who has Tourette’s syndrome. -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

Done 2002 Jan 15.Pmd

January 15th, 2002 The Abaconian 1 VOLUME 10, NUMBER 2, JANUARY 15th, 2002 VOLUME 10, NUMBER 2, JANUARY 15th, 2002 Voter Cards Are Issued National Elections Will Be Called in Early Spring The distribution of voters cards began on January 7 throughout the Bahamas. The Junkanoo Entertains Green Turtle Cay cards can be picked up at the Administra- tors’ offices o other government offices des- ignated by the Administrators. The officials would like voters to pick up their cards and inform the officials if they have moved. Some people who have moved will now be eligible to vote in a different constituency or polling division if they have lived in the new polling division for at least three months. The Parliamentary Commissioner, Mr. Errol Bethel, is wanting to have as ac- curate a register as possible. Voter registration was opened on Novem- ber 6, 2000, and more than 121,000 people have registered. The voter registration is continuing and voters are urged to register as soon as possible. The register will re- main open until the time an election is called. At that point the register is closed. The government were not able to give out voters cards until the boundaries for the con- Please see Voter Cards Page 14 Santa Sails to Green Turtle Cay Crowds filled the narrow streets of Green Turtle Cay on January 1 for the town’s annual Junkanoo rush. They were thrilled by the dancing and costumes as the revelers paraded through town accompanied by a brass section this year. The festivities were interrupted by a fight which brought the event to an abrupt end.