The Beauty of Man a Synopsis of St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

Biography of Pope John Paul Ii Pdf

Biography of pope john paul ii pdf Continue John Paul II (1920-2005) CAROL JASEF VODYA, elected Pope on October 16, 1978, was born on May 18, 1920, in Wadowice, Poland. He was the third of three children born to Karol Oytytya and Emilia Kakovsky, who died in 1929. His older brother Edmund, a doctor, died in 1932, and his father, Carol, a non-commissioned officer in the army, died in 1941. He was nine years old when he received his First Communion and eighteen years when he received the Sacrament of Confirmation. After graduating from high school in Vadowice, he enrolled at the University of Jagelon in Krakow in 1938. When the Nazi occupying forces closed the university in 1939, Karol worked (1940-1944) in a quarry and then at the Solvea chemical plant to earn a living and avoid deportation to Germany. Feeling called to the priesthood, he began his studies in 1942 at a secret large seminary in Krakow under the direction of Archbishop Adam Stefan Sapiehi. At the time, he was one of the organizers of the Rhapsodic Theatre, which was also underground. After the war, Carol continued his studies at the main seminary, recently reopened, and at the School of Theology at Jagelon University, before his priestly ordination in Krakow on November 1, 1946. Father Oytysha was then sent by Cardinal Sapieha to Rome, where he received his doctorate in theology (1948). He wrote his thesis on faith, as is understood in the works of St. John the Cross. As a student in Rome, he spent his holidays performing pastoral service with Polish expats in France, Belgium and Holland. -

Pontifical John Paul Ii Institute for Studies on Marriage & Family

PONTIFICAL JOHN PAUL II INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES ON MARRIAGE & FAMILY at The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. ACADEMIC CATALOG 2011 - 2013 © Copyright 2011 Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family at The Catholic University of America Cover photo by Tony Fiorini/CUA 2JOHN PAUL II I NSTITUTE TABLE OF CONTENTS MISSION STATEMENT 4 DEGREE PROGRAMS 20 The Master of Theological Studies NATURE AND PURPOSE in Marriage and Family OF THE INSTITUTE 5 (M.T.S.) 20 The Master of Theological Studies GENERAL INFORMATION 8 in Biotechnology and Ethics 2011-12 A CADEMIC CALENDAR 10 (M.T.S.) 22 The Licentiate in Sacred Theology STUDENT LIFE 11 of Marriage and Family Facilities 11 (S.T.L.) 24 Brookland/CUA Area 11 Housing Options 11 The Doctorate in Sacred Theology Meals 12 with a Specialization in Medical Insurance 12 Marriage and Family (S.T.D.) 27 Student Identification Cards 12 The Doctorate in Theology with Liturgical Life 12 a Specialization in Person, Dress Code 13 Marriage, and Family (Ph.D.) 29 Cultural Events 13 Transportation 13 COURSES OF INSTRUCTION 32 Parking 14 FACULTY 52 Inclement Weather 14 Post Office 14 THE MCGIVNEY LECTURE SERIES 57 Student Grievances 14 DISTINGUISHED LECTURERS 57 Career and Placement Services 14 GOVERNANCE & A DMINISTRATION 58 ADMISSIONS AND FINANCIAL AID 15 STUDENT ENROLLMENT 59 TUITION AND FEES 15 APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION ACADEMIC INFORMATION 16 MAGNUM MATRIMONII SACRAMENTUM 62 Registration 16 Academic Advising 16 PAPAL ADDRESS TO THE FACULTY OF Classification of Students 16 Auditing -

John Paul II and Children's Education Christopher Tollefsen

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 21 Article 6 Issue 1 Symposium on Pope John Paul II and the Law 1-1-2012 John Paul II and Children's Education Christopher Tollefsen Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Christopher Tollefsen, John Paul II and Children's Education, 21 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 159 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol21/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN PAUL H AND CHILDREN'S EDUCATION CHRISTOPHER TOLLEFSEN* Like many other moral and social issues, children's educa- tion can serve as a prism through which to understand the impli- cations of moral, political, and legal theory. Education, like the family, abortion, and embryonic research, capital punishment, euthanasia, and other issues, raises a number of questions, the answers to which are illustrative of a variety of moral, political, religious, and legal standpoints. So, for example, a libertarian, a political liberal, and a per- fectionist natural lawyer will all have something to say about the question of who should provide a child's education, what the content of that education should be, and what mechanisms for the provision of education, such as school vouchers, will or will not be morally and politically permissible. -

Gerard Mannion Is to Be Congratulated for This Splendid Collection on the Papacy of John Paul II

“Gerard Mannion is to be congratulated for this splendid collection on the papacy of John Paul II. Well-focused and insightful essays help us to understand his thoughts on philosophy, the papacy, women, the church, religious life, morality, collegiality, interreligious dialogue, and liberation theology. With authors representing a wide variety of perspectives, Mannion avoids the predictable ideological battles over the legacy of Pope John Paul; rather he captures the depth and complexity of this extraordinary figure by the balance, intelligence, and comprehensiveness of the volume. A well-planned and beautifully executed project!” —James F. Keenan, SJ Founders Professor in Theology Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts “Scenes of the charismatic John Paul II kissing the tarmac, praying with global religious leaders, addressing throngs of adoring young people, and finally dying linger in the world’s imagination. This book turns to another side of this outsized religious leader and examines his vision of the church and his theological positions. Each of these finely tuned essays show the greatness of this man by replacing the mythological account with the historical record. The straightforward, honest, expert, and yet accessible analyses situate John Paul II in his context and show both the triumphs and the ambiguities of his intellectual legacy. This masterful collection is absolutely basic reading for critically appreciating the papacy of John Paul II.” —Roger Haight, SJ Union Theological Seminary New York “The length of John Paul II’s tenure of the papacy, the complexity of his personality, and the ambivalence of his legacy make him not only a compelling subject of study, but also a challenging one. -

![Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8427/vincentiana-vol-49-no-2-full-issue-778427.webp)

Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]

Vincentiana Volume 49 Number 2 Vol. 49, No. 2 Article 1 2005 Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2005) "Vincentiana Vol. 49, No. 2 [Full Issue]," Vincentiana: Vol. 49 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol49/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University Vincentiana (English) Vincentiana 4-30-2005 Volume 49, no. 2: March-April 2005 Congregation of the Mission Recommended Citation Congregation of the Mission. Vincentiana, 49, no. 2 (March-April 2005) This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentiana at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana (English) by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VINCENTIANA 49" YEAR-N.2 MARCH-APRII. 2005 Vincentian Ongoing Formation CONGREGATION OF TIIF. MISSION GFNERAI CURIA VINCENTIANA Magazine of the Congregation of the Mission published every two months Holy See 1 1 i holy Father in the Father's (louse 49' Year - N. 2 11.4 Appointment March-April 2005 11-1 Ilabenius Papam! Editor Alfredo Becerro Vazquez, C.M. -

(Mk 1:22). on the Role of Wonderment in the Theological Method

Teologia w Polsce 14,2 (2020), s. 49–62 10.31743/twp.2020.14.2.03 Fr. Cezary Smuniewski* Akademia Sztuki Wojennej, Warszawa “ET STUPEBANT SUPER DOCTRINA EJUS” (MK 1:22). ON THE ROLE OF WONDERMENT IN THE THEOLOGICAL METHOD The study is a contribution to research on the theological method and shows the motif of wonderment in the teaching and poetry of John Paul II as an experience inviting man to get to know God and His works ever more deeply. The human experience of being amazed with God has been presented as a theological event – a grace of the ability to stand in awe of God, to get closer to Him and to speak about Him. The author of the article comes to the conclusion that the mission of a theologian is inseparably connected with cultivating the ability to be amazed with God and His works. The experience of wonderment is one of the elements leading to communion with Christ the Theologian, who reveals the Father. INTRODUCTION The aim of this study is to show the motif of wonderment and at the same time to try to recognize in this motif the content that can be useful in research on the theological method and thus indirectly on the mission of the theologian. The choice of sources which became the basis for the analysis was determined by the main idea – striving to show wonderment as one of the elements influencing the theological thinking and the experience of faith. The quoted documents and studies were selected with regard to their relation to the theological and semantic problem space, defined by the main goal. -

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

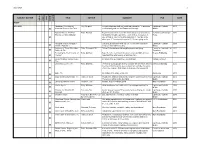

2/25/2020 1 SUBJECT MATTER TITLE AUTHOR SUMMARY PUB DATE DVD gdom VIDEO AUDIO OTHER OTHER AUDIO 2/12/2020 Abraham: Revealing the Ray, Stephen To understand our faith, we must understand the "Jewishness" Lighthouse Catholic 2011 x Historical Roots of our Faith of Christianity and our Old Testament Heritage Media Adam's Return: The Five Rohr, Richard Boys become men in much the same way across cultures, by St. Anthony Messenger 2006 Promises of Male Initiation integrating, through experience, each of these messages: 1. Press x Life is hard; 2. You are not that important; 3. Your life is not about you; 4. You are not in control; 5. You are going to die. Amazing Angels and Super Cat.Chat, designed for kids ages 3-11, to teach lessons for Lighthouse Catholic 2008 x Saints - Episode 1 living out their faith every day Media Authority of Those Who Have Rohr, Richard OFM Father Richard shares his insights on pain and dying Center for Loss and Life 2005 x Suffered, The Transition Becoming the Best Version of Kelly, Matthew Take life to the next level: who you become is infinitely more Beacon Publishing 1999 x Yourself important than what you do or what you have. Best of Catholic Answers Live, 47 answers to questions from non-Catholics Catholic Answers x The Best Way to Live, The Kelly, Matthew Perfect for young paople as they consider the life before them at Beacon Publishing 2012 the time of Confirmation; also an important reminder for adults x of any age, and one that is sure to help you refocus your life x Bible, The Recitation of the Bible on 64 cd's Zondervan 2001 Body and Blood of Christ, The Hahn, Dr. -

The BG News March 25, 2004

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-25-2004 The BG News March 25, 2004 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News March 25, 2004" (2004). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7259. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7259 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University THURSDAY March 25, 2004 SHOWERS HIGH: 631 LOW: 54 www.bgnews.com independent student press VOLUME 98 ISSUE 117 Alumni speaks about STAND By Monica Frost seen and heard throughout Ohio for the STAND'S campaign strategy moves up a based groups. REPORTER past three years in print ads as well as hierarchy of education and awareness, "It's kids talking to kids," Miller said of Rick Miller, a 1979 University graduate, radio and television spots. empowerment, activism and the ultimate STAND'S street-approach. "It's people shared with students and faculty yestei- Miller's speech was titled "Apathy to goal of a cultural shift where "tobacco is talking from their hearts about something day evening some very interesting num- Advocacy: Changing Ohio's Culture no longer culturally accepted in Ohio," that's tmly important to them." bers concerning tobacco use in the state Regarding Tobacco Use" and was a pan of Miller said. -

Dominum Et Vivificantem

SUMMARY Year 2003 marks the 25th anniversary of Card. Karol Wojtyła’s appointment to Peter’s See. The present volume of the Ethos, entitled T he Ethos of the Pilgrim, is thought as an attempt to point to the most genuine aspect of this outstandingly prolific pontificate. This special attribute of John Paul II*s pontificate can be perceived in the fact that the Pope has construed his mission as that of a Pilgrim. Indeed, peregrination appears to constitute a special dimension of John Paul II’s service to humanity. Pilgrimages have been a most significant instrument of the Holy Father’s apostolic mission already sińce the start of the pontificate, beginning with the trip to Santo Domingo and Mexico in January 1979. Actually, the agenda of John Paul II’s pontificate, which was to become a Pilgrim one, was clearly outlined in the homily delivered by the Pope in Victory Sąuare in Warsaw on 2 June 1979. The Holy Father said then: “Once the Church has realized anew that being the People of God she participates in the mission of Christ, that she is the People that conducts this mission in history, that the Church is a «pilgrim» people, the Pope can no longer remain a prisoner in the Vatican. He has had no other choice, but to become, once again, pilgrim-Peter, just like St. Peter himself, who became a pilgrim from Antioch to Rome in order to bear witness to Christ and to sign it with his blood.” From the perspective of the last 25 years one can observe a perfect coherence that marks the implementation of this agenda. -

From Memory to Freedom Research on Polish Thinking About National Security and Political Community

Cezary Smuniewski From Memory to Freedom Research on Polish Thinking about National Security and Political Community Publication Series: Monographs of the Institute of Political Science Scientific Reviewers: Waldemar Kitler, War Studies Academy, Poland Agostino Massa, University of Genoa, Italy The study was performed under the 2017 Research and Financial Plan of War Studies Academy. Title of the project: “Bilateral implications of security sciences and reflection resulting from religious presumptions” (project no. II.1.1.0 grant no. 800). Translation: Małgorzata Mazurek Aidan Hoyle Editor: Tadeusz Borucki, University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland Typeseting: Manuscript Konrad Jajecznik © Copyright by Cezary Smuniewski, Warszawa 2018 © Copyright by Instytut Nauki o Polityce, Warszawa 2018 All rights reserved. Any reproduction or adaptation of this publication, in whole or any part thereof, in whatever form and by whatever media (typographic, photographic, electronic, etc.), is prohibited without the prior written consent of the Author and the Publisher. Size: 12,1 publisher’s sheets Publisher: Institute of Political Science Publishers www.inop.edu.pl ISBN: 978-83-950685-7-7 Printing and binding: Fabryka Druku Contents Introduction 9 1. Memory - the “beginning” of thinking about national security of Poland 15 1.1. Memory builds our political community 15 1.2. We learn about memory from the ancient Greeks and we experience it in a Christian way 21 1.3. Thanks to memory, we know who a human being is 25 1.4. From memory to wisdom 33 1.5. Conclusions 37 2. Identity – the “condition” for thinking about national security of Poland 39 2.1. Contemporary need for identity 40 2.2. -

177618331.Pdf

Christian Identity Studies in Reformed Theology Editor-in-chief Eduardus Van der Borght, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Editorial Board Abraham van de Beek, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Martien Brinkman, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Alasdair Heron, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, emeritus Dirk van Keulen, Leiden University Daniel Migliore, Princeton Theological Seminary Richard Mouw, Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena Gerrit Singgih, Duta Wacana Christian University, Yogjakarta Conrad Wethmar, University of Pretoria VOLUME 16 Christian Identity Edited by Eduardus Van der Borght LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Reformed Theological Institute. International Conference (6th : 2005 : Seoul, Korea) Christian identity / edited by Eduardus van der Borght. p. cm. -- (Studies in reformed theology ; v. 16) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-15806-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Identification (Religion)--Congresses. 2. Reformed Church–Doctrines--Congresses. I. Borght, Ed. A. J. G. van der, 1956- II. Title. III. Series. BV4509.5.I58 2005 261.2--dc22 2008018712 ISSN 1571-4799 ISBN 978 90 04 15806 1 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA.