On Moral Understanding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optimistic Realism About Scientific Progress

Optimistic Realism about Scientific Progress Ilkka Niiniluoto ABSTRACT: Scientific realists use the “no miracle argument” to show that the empirical and pragmatic success of science is an indicator of the ability of scientific theories to give true or truthlike representations of unobservable reality. While antirealists define scientific progress in terms of empirical success or practical problem-solving, realists characterize progress by using some truth-related criteria. This paper defends the definition of scientific progress as increasing truthlikeness or verisimilitude. Antirealists have tried to rebut realism with the “pessimistic metainduction”, but critical realists turn this argument into an optimistic view about progressive science. KEYWORDS: conceptual pluralism, fallibilism, no miracle argument, pessimistic metainduction, scientific realism, truthlikeness 1. Varieties of Scientific Realism Scientific realism as a philosophical position has (i) ontological, (ii) semantical, (iii) epistemological, (iv) theoretical, and (v) methodological aspects (see Niiniluoto 1999a; Psillos 1999). It holds that (i) at least part of reality is ontologically independent of human mind and culture. It takes (ii) truth to involve a non-epistemic relation between language and reality. It claims that (iii) knowledge about mind-independent (as well as mind-dependent) reality is possible, and that (iv) the best and deepest part of such knowledge is provided by empirically testable scientific theories. An important aim of science is (v) to find true and informative theories which postulate non-observable entities and laws to explain observable phenomena. Scientific realism became a tenable stance in the philosophy of science in the 1950s as an alternative to empiricist views which reduced theories to the observational language (Ernst Mach’s positivism) or restricted scientific knowledge to the level of observational statements by denying that theoretical statements have truth values (Pierre Duhem’s instrumentalism). -

What to Be Realist About in Linguistic Science

What to be realist about in linguistic science Geoffrey K. Pullum School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh This paper was presented at a workshop entitled ‘Foundation of Linguistics: Languages as Abstract Objects’ at the Technische Universitat¨ Carolo-Wilhelmina in Braunschweig, Germany, June 25–28. At the end of his viva, Hilary Putnam asked him, “And tell us, Mr. Boolos, what does the analytical hierarchy have to do with the real world?” Without hesitating Boolos replied, “It’s part of it.” [From the Wikipedia article on the MIT logician George Boolos] Prefatory remarks on realism I need to begin by clarifying what is meant (or at least, what I and others have meant) by ‘realism’. That such clarification is necessary is indicated by the fact that the subtitle of this workshop (‘Lan- guages as Abstract Objects’) clearly pays homage to Katz (1981) (Language and Other Abstract Objects). What the late Jerrold J. Katz meant by the word ‘realism’ does not comport with the usage of most philosophers. Katz shows little interest in defining his terms. He barely even waves a hand in that direc- tion. The third page of Language and Other Abstract Objects book announces that he has had an epiphany: there is “an alternative to both the American structuralists’ and the Chomskian concep- tion of what grammars are theories of, namely, the Platonic realist view that grammars are theories of abstract objects (sentences)” (Katz 1981, 3). Neither ‘Platonic’ nor ‘realist’ are analysed, expli- cated, or even glossed at this point. ‘Platonic realism’ is thereafter abbreviated to ‘Platonism’ and simply assumed to be understood. -

Models, Perspectives, and Scientific Realism

MODELS, PERSPECTIVES, AND SCIENTIFIC REALISM: ON RONALD GIERE'S PERSPECTIVAL REALISM A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Brian R. Huth May, 2014 Thesis written by Brian R. Huth B.A., Kent State University 2012 M.A., Kent State University 2014 Approved by Frank X. Ryan, Advisor Linda Williams, Chair, Department of Philosophy James L. Blank, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER I. FROM THE RECEIVED VIEW TO THE MODEL-THEORETIC VIEW........................................................................................................... 7 Section 1.1.................................................................................................... 9 Section 1.2.................................................................................................... 16 II. RONALD GIERE'S CONSTRUCTIVISM AND PERSPECTIVAL REALISM.................................................................................................... 25 Section 2.1.................................................................................................... 25 Section 2.2.................................................................................................... 31 Section 2.3................................................................................................... -

Socrates, Phil Inquiry & the Elenctic Method (F11new)

PLATO, PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY & THE ELENCTIC METHOD All human beings, by their nature, desire understanding. — Aristotle, Metaphysics (Book 1) The safest general characterisation of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. — Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality The elenctic method (part 1): on Meno’s enumerative THE BIG IDEAS TO MASTER definition of (human) virtue • Theory • Socratic humility On Platonic realism & Socratic definitions. According to Plato, a • The elenctic method central part of philosophical inquiry involves an attempt to • Platonic realism understand the Forms. This implies that he is committed the view • Platonic Forms we will call Platonic realism, namely, the view that • Socratic definitions • Essences Platonic realism. The Forms exist. • Natural kinds vs. artefacts • Abstract vs. concrete entities So, according to this theory, Reality contains the Forms. But what • Essential vs. accidental properties are the Forms? That question is best answered as follows. Much of • Counterexample the most important research that philosophers and other scholars do • Reductio ad absurdum argument involves an attempt to answer questions of the form ‘what is x?’ • Sound argument Physicists, for instance, ask ‘what is a black hole?’; biologists ask • Valid argument ‘what is an organism?’; mathematicians ask ‘what is a right triangle?’ • The correspondence theory of truth Let us call the correct answer to a what-is-x question the Socratic • Fact definition of x. We can say, then, that physicists are seeking the Socratic definition of a black hole, biologists investigate the Socratic definition of an organism, and mathematicians look to determine the Socratic definition of a right triangle. -

The American Philosophical Association PACIFIC DIVISION EIGHTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM

The American Philosophical Association PACIFIC DIVISION EIGHTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM WESTIN GASLAMP QUARTER AND U.S. GRANT HOTEL SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA APRIL 16 – 20, 2014 : new books for spring HUMOR AND THE GOOD LIFE REPRODUCTION, RACE, IN MODERN PHILOSOPHY AND GENDER IN PHILOSOPHY Shaftesbury, Hamann, Kierkegaard AND THE EARLY LIFE SCIENCES Lydia B. Amir Susanne Lettow, editor (February) (March) PHILOSOPHIZING AD INFINITUM LEO STRAUSS AND THE CRISIS infinite Nature, infinite Philosophy OF RATIONALISM Marcel Conche Another Reason, Another Enlightenment Laurent Ledoux and Corine Pelluchon Herman G. Bonne, translators Robert Howse, translator Foreword by J. Baird Callicott (February) (June) NIHILISM AND METAPHYSICS HABITATIONS OF THE VEIL The Third Voyage Metaphor and the Poetics of Black Being Vittorio Possenti in African American Literature Daniel B. Gallagher, translator Rebecka Rutledge Fisher Foreword by Brian Schroeder (May) (April) THE LAWS OF THE SPIRIT LACan’s etHics and nietzscHe’s A Hegelian Theory of Justice CRITIQUE OF PLATONISM Shannon Hoff Tim Themi (April) (May) AFTER LEO STRAUSS EMPLOTTING VIRTUE New Directions in Platonic A Narrative Approach Political Philosophy to Environmental Virtue Ethics Tucker Landy Brian Treanor (June) (June) LIVING ALTERITIES FEMINIST PHENOMENOLOGY Phenomenology, Embodiment, and Race AND MEDICINE Emily S. Lee, editor Kristin Zeiler and (April) Lisa Folkmarson Käll, editors (April) LUCE IRIGARAY’s PHenomenoLOGY OF FEMININE BEING Please visit our website for information Virpi Lehtinen on our philosophy journals. (June) SPECIAL EVENTS Only registrants are entitled to attend the reception on April 17 at no additional charge. Non-registrants, such as spouses, partners, or family members of meeting attendees, who wish to accompany a registrant to this reception must purchase a $10 guest ticket; guest tickets are available at the reception door as well as in advance at the registration desk. -

CHAPTER 1 and Unexemplified Properties, Kinds, and Relations

UNIVERSALS I: METAPHYSICAL REALISM existing objects; whereas other realists believe that there are both exemplified CHAPTER 1 and unexemplified properties, kinds, and relations. The problem of universals I Realism and nominalism The objects we talk and think about can be classified in all kinds of Metaphysical realism ways. We sort things by color, and we have red things, yellow things, and blue things. We sort them by shape, and we have triangular things, circular things, and square things. We sort them by kind, and 0 Realism and nominalism we have elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. The kind of classification The ontology of metaphysical realism at work in these cases is an essential component in our experience of the Realism and predication world. There is little, if anything, that we can think or say, little, if anything, that counts as experience, that does not involve groupings of Realism and abstract reference these kinds. Although almost everyone will concede that some of our 0 Restrictions on realism - exemplification ways of classifying objects reflect our interests, goals, and values, few 0 Further restrictions - defined and undefined predicates will deny that many of our ways of sorting things are fixed by the 0 Are there any unexemplified attributes? objects themselves.' It is not as if we just arbitrarily choose to call some things triangular, others circular, and still others square; they are tri- angular, circular, and square. Likewise, it is not a mere consequence of Overview human thought or language that there are elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. They come that way, and our language and thought reflect The phenomenon of similarity or attribute agreement gives rise to the debate these antecedently given facts about them. -

Universals.Pdf

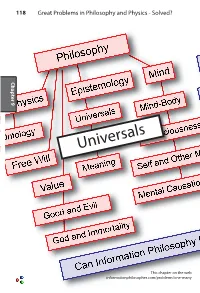

118 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 9 Chapter Universals This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/one-many Universals 119 Universals A “universal” in metaphysics is a property or attribute that is shared by many particular objects (or concepts). It has a subtle relationship to the problem of the one and the many. It is also the question of ontology.1 What exists in the world? Ontology is intimately connected with epistemology - how can we know what exists in the world? Knowledge about objects consists in describing the objects with properties and attributes, including their relations to other objects. Rarely are individual properties unique to an individual object. Although a “bundle of properties” may uniquely charac- 9 Chapter terize a particular individual, most properties are shared with many individuals. The “problem of universals” is the existential status of a given shared property. Does the one universal property exist apart from the many instances in particular objects? Plato thought it does. Aristotle thought it does not. Consider the property having the color red. Is there an abstract concept of redness or “being red?” Granted the idea of a concept of redness, in what way and where in particular does it exist? Nomi- nalists (sometimes called anti-realists) say that it exists only in the particular instances, and that redness is the name of this property. Conceptualists say that the concept of redness exists only in the minds of those persons who have grasped the concept of redness. They might exclude color-blind persons who cannot perceive red. -

1. Armstrong and Aristotle There Are Two Main Reasons for Not

RECENSIONI&REPORTS report ANNABELLA D’ATRI DAVID MALET ARMSTRONG’S NEO‐ARISTOTELIANISM 1. Armstrong and Aristotle 2. Lowe on Aristotelian substance 3. Armstrong and Lowe on the laws of nature 4. Conclusion ABSTRACT: The aim of this paper is to establish criteria for designating the Systematic Metaphysics of Australian philosopher David Malet Armstrong as neo‐ Aristotelian and to distinguish this form of weak neo‐ Aristotelianism from other forms, specifically from John Lowe’s strong neo‐Aristotelianism. In order to compare the two forms, I will focus on the Aristotelian category of substance, and on the dissimilar attitudes of Armstrong and Lowe with regard to this category. Finally, I will test the impact of the two different metaphysics on the ontological explanation of laws of nature. 1. Armstrong and Aristotle There are two main reasons for not considering Armstrong’s Systematic Metaphysics as Aristotelian: a) the first is a “philological” reason: we don’t have evidence of Armstrong reading and analyzing Aristotle’s main works. On the contrary, we have evidence of Armstrong’s acknowledgments to Peter Anstey1 for drawing his attention to the reference of Aristotle’s theory of truthmaker in Categories and to Jim Franklin2 for a passage in Aristotle’s Metaphysics on the theory of the “one”; b) the second reason is “historiographic”: Armstrong isn’t listed among the authors labeled as contemporary Aristotelian metaphysicians3. Nonetheless, there are also reasons for speaking of Armstrong’s Aristotelianism if, according to 1 D. M. Armstrong, A World of State of Affairs, Cambridge University Press, New York 1978, p. 13. 2 Ibid., p. -

DICTIONARY of PHILOSOPHY This Page Intentionally Left Blank

A DICTIONARY OF PHILOSOPHY This page intentionally left blank. A Dictionary of Philosophy Third edition A.R.Lacey Department of Philosophy, King’s College, University of London First published in 1976 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd Second edition 1986 Third edition 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © A.R.Lacey 1976, 1986, 1996 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Lacey, A.R. A dictionary of philosophy.—3rd edn. 1. Philosophy—Dictionaries I. Title 190′.3′21 B41 ISBN 0-203-19819-0 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-19822-0 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-13332-7 (Print Edition) Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available on request Preface to the first edition This book aims to give the layman or intending student a pocket encyclopaedia of philosophy, one with a bias towards explaining terminology. The latter task is not an easy one since philosophy is regularly concerned with concepts which are unclear. -

What Would It Mean to Directly Observe Electrons?

WHAT WOULD IT MEAN TO DIRECTLY OBSERVE ELECTRONS? DAVID MITSUO NIXON University of Washington Abstract In this paper it is argued that a proper understanding of the justification of perceptual beliefs leaves open the possibility that normal humans, unaided by microscopes, could genuinely know, by direct observation, of the existence of a theoretical entity like an electron. A particular theory of justification called perceptual responsibilism is presented. If successful, this kind of view would undercut one line of argument that has been given (for example, by Bas van Fraassen) in support of scientific anti-realism. Various objections to the idea that electrons can be directly observed are also considered. Scientific anti-realism is, roughly, the view that we are not justified in believing in the existence of theoretical entities—of which I take elec- trons to be a paradigm example. Such a view obviously relies on the distinction between things that are directly observable and things that are not, where theoretical entities would fall into the latter category. In this paper I will argue against this distinction—at least in the sense in which it is required by scientific anti-realism. I will argue that (so- called) theoretical entities like electrons can be observed by normal humans. In taking aim at scientific anti-realism, I will primarily have in mind its leading proponent, Bas van Fraassen. But it is important to keep in mind that while my narrow concern in this paper is the issue of the justification of observational beliefs, van Fraassen’s constructive em- piricism encompasses much more than that. -

“Karl Jaspers Forum” Update 17 (4-1-2006) Historical

THE “KARL JASPERS FORUM” UPDATE 17 (4-1-2006) HISTORICAL EXAMPLE FOR GOING BEYOND EPISTEMIC NAUGHT THINKING Notation: This week Herbert’s Website includes his Comment to Mr. Barros, and a Comment from Sid Barnett. None make reference to Jaspers. None can find an appropriate connection with Jaspers. FOR QUICK REFERENCE: 1. Herbert avoids historical reality by naught “0” bubbles 1.3. Historical example of naught thinking—David Hume and a Scottish movement 2. Sid Barnett’s Radical Constructivism resurgence 3. David Hume as cypher of meaning and the Vanity Press 1. Herbert avoids Complicated Historical analysis--This week (4-1-2006) Herbert informs Mr. Rodrigo Barros Gewehr that his, Herbert’s, presentations are to be viewed as primarily epistemological rather than from “the ethical point”. What Herbert is under compulsion to do here is place an absolute barrier between traditional values and his constructionism’s (radical constructivism) formulae. Herbert uses the word epistemology to imply that he has reduced truth standards to a system that because systematic it must be yielded to as science. In effect it is a complex tool to escape real situations, i.e., to avoid the complicated relativity of complex reality. It is a system encompassed by a know- it-all metaphysic. Herbert’s superficial epistemological system is modifiable more by the word ideal rather than the word real. Epistemological idealism has at least ten modifications and realistic epistemology has at least a dozen when subjected to detailed analysis (such as the study done by Celestine N. Bittle in Reality and the Mind). It is further complicated by a variety of categorizations depending on whether for some special or general frame of reference one comes down on the real-ideal or the ideal-real side of the bounding bouncing epistemological…bubble. -

Ontological, Epistemological, and Methodological Positions

ONTOLOGICAL, EPISTEMOLOGICAL, AND METHODOLOGICAL POSITIONS James Ladyman INTRODUCTION This chapter summarises various important ontological, epistemological and methodological issues in the philosophy of science. Ontology is the theory of what exists and is the foremost concern of metaphysics, which is the study of the most fundamental questions about being and the nature of reality. Ontological issues in the philosophy of science may be specific to a particular special science, such as questions about the ontological status of biological species, or they may be more general, such as whether or not there are objective natural kinds. In the history of science ontological issues have often been of supreme importance; for example, whether or not atoms exist was a question that occupied many scientists in the nineteenth century. In what follows, some fundamental questions of ontology are discussed, some of which, such as those concerning laws of nature, are also ad- dressed in analytic metaphysics. A number of these issues also relate to debates in the foundations of physics about the ontological implications of our best physical theories. Readers who wish to know more about the philosophy of space and time and the nature of matter and motion should consult the companion volume to this on the philosophy of physics. Epistemology is the theory of knowledge and as such is concerned with such matters as the analysis of knowledge and its relationship to belief and truth, the theory of justification, and how to respond to the challenge of local scepticism, say about the past, or global scepticism, which suggests that there is no knowledge.