1. Armstrong and Aristotle There Are Two Main Reasons for Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Be Realist About in Linguistic Science

What to be realist about in linguistic science Geoffrey K. Pullum School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh This paper was presented at a workshop entitled ‘Foundation of Linguistics: Languages as Abstract Objects’ at the Technische Universitat¨ Carolo-Wilhelmina in Braunschweig, Germany, June 25–28. At the end of his viva, Hilary Putnam asked him, “And tell us, Mr. Boolos, what does the analytical hierarchy have to do with the real world?” Without hesitating Boolos replied, “It’s part of it.” [From the Wikipedia article on the MIT logician George Boolos] Prefatory remarks on realism I need to begin by clarifying what is meant (or at least, what I and others have meant) by ‘realism’. That such clarification is necessary is indicated by the fact that the subtitle of this workshop (‘Lan- guages as Abstract Objects’) clearly pays homage to Katz (1981) (Language and Other Abstract Objects). What the late Jerrold J. Katz meant by the word ‘realism’ does not comport with the usage of most philosophers. Katz shows little interest in defining his terms. He barely even waves a hand in that direc- tion. The third page of Language and Other Abstract Objects book announces that he has had an epiphany: there is “an alternative to both the American structuralists’ and the Chomskian concep- tion of what grammars are theories of, namely, the Platonic realist view that grammars are theories of abstract objects (sentences)” (Katz 1981, 3). Neither ‘Platonic’ nor ‘realist’ are analysed, expli- cated, or even glossed at this point. ‘Platonic realism’ is thereafter abbreviated to ‘Platonism’ and simply assumed to be understood. -

On Moral Understanding

COMMENTTHE COLLEGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE NO 147 | MAY 2003 TOM WHIPPS On Moral Understanding DNA pioneers: The surviving members of the King’s team, who worked on the discovery of the structure of DNA 50 years ago, withDavid James Watson, K Levytheir Cambridge ‘rival’ at the time. From left Ray Gosling, Herbert Wilson, DNA at King’s: DepartmentJames Watson and of Maurice Philosophy Wilkins King’s College the continuing story University of London Prize for his contribution – and A day of celebrations their teams, but also to subse- quent generations of scientists at ver 600 guests attended a cant scientific discovery of the King’s. unique day of events celeb- 20th century,’ in the words of Four Nobel Laureates – Mau- Orating King’s role in the 50th Principal Professor Arthur Lucas, rice Wilkins, James Watson, Sid- anniversary of the discovery of the ‘and their research changed ney Altman and Tim Hunt – double helix structure of DNA on the world’. attended the event which was so 22 April. The day paid tribute not only to oversubscribed that the proceed- Scientists at King’s played a King’s DNA pioneers Rosalind ings were relayed by video link to fundamental role in this momen- Franklin and Maurice Wilkins – tous discovery – ‘the most signifi- who went onto win the Nobel continued on page 2 2 Funding news | 3 Peace Operations Review | 5 Widening participation | 8 25 years of Anglo-French law | 11 Margaret Atwood at King’s | 12 Susan Gibson wins Rosalind Franklin Award | 15 Focus: School of Law | 16 Research news | 18 Books | 19 KCLSU election results | 20 Arts abcdef U N I V E R S I T Y O F L O N D O N A C C O M M O D A T I O N O F F I C E ACCOMMODATION INFORMATION - FINDING SOMEWHERE TO LIVE IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy WARNING: Under no circumstances inshould the this University document be of taken London as providing legal advice. -

Aquinas on Attributes

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by MedievaleCommons@Cornell Philosophy and Theology 11 (2003), 1–41. Printed in the United States of America. Copyright C 2004 Cambridge University Press 1057-0608 DOI: 10.1017/S105706080300001X Aquinas on Attributes BRIAN LEFTOW Oriel College, Oxford Aquinas’ theory of attributes is one of the most obscure, controversial parts of his thought. There is no agreement even on so basic a matter as where he falls in the standard scheme of classifying such theories: to Copleston, he is a resemblance-nominalist1; to Armstrong, a “concept nominalist”2; to Edwards and Spade, “almost as strong a realist as Duns Scotus”3; to Gracia, Pannier, and Sullivan, neither realist nor nominalist4; to Hamlyn, the Middle Ages’ “prime exponent of realism,” although his theory adds elements of nominalism and “conceptualism”5; to Wolterstorff, just inconsistent.6 I now set out Aquinas’ view and try to answer the vexed question of how to classify it. Part of the confusion here is terminological. As emerges below, Thomas believed in “tropes” of “lowest” (infima) species of accidents and (I argue) substances.7 Many now class trope theories as a form of nominalism,8 while 1. F. C. Copleston, Aquinas (Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1955), P. 94. 2. D. M. Armstrong, Nominalism and Realism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 25, 83, 87. Armstrong is tentative about this. 3. Sandra Edwards, “The Realism of Aquinas,” The New Scholasticism 59 (1985): 79; Paul Vincent Spade, “Degrees of Being, Degrees of Goodness,” in Aquinas’ Moral Theory, ed. -

SYSTEMATIC METAPHYSICS, OXFORD 2010 (1ª Ed.), 138 Páginas: OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Aporía • Revista Internacional ISSN 0718-9788 de Investigaciones Filosóficas Diego Morales Pérez Artículos /Articles Nº 5 (2013), pp. 86-89 Santiago de Chile DAVID MALET ARMSTRONG, SKETCH FOR A SYSTEMATIC METAPHYSICS, OXFORD 2010 (1ª Ed.), 138 páginas: OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Diego Morales Pérez1 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Sketch for a Systematic Metaphysics, publicado por Oxford University Press en el año 2010, es una de las obras más recientes que nos ofrece el célebre profesor australiano D.M. Armstrong. En este breve libro, el lector puede encontrar un conciso resumen de las ideas y opiniones más recientes del autor sobre los temas que deben conformar, a su juicio, un programa de investigación serio en metafísica. Es así como el texto trata los siguientes temas: 1. Propiedades; 2. Relaciones; 3. Estados de Cosas; 4. Leyes de la Naturaleza; 5. Reacción contra el Disposicionalismo; 6. Particulares; 7. Truthmakers; 8. Posibilidad, Actualidad y Necesidad; 9. Límites; 10. Ausencias; 11. Las Disciplinas Racionales: Lógica y Matemática; 12. Números; 13. Clases; 14. Tiempo; 15. Mente. El sello distintivo que presenta esta obra, en comparación a otras que entregan panoramas generales sobre temas recurrentes en metafísica, es la intención del autor de articular los contenidos de manera “sistemática”. En el prefacio Armstrong nos dice que la metafísica, disciplina que se ha vuelto respetable una vez más, está siendo trabajada por pensadores muy talentosos, pero de manera inconexa y a pedazos (p. X). Sería provechoso, entonces, presentar una propuesta que articule los contenidos, aprovechando de dar su opinión en cada uno de ellos. Ahora bien, el autor no se pronuncia explícitamente sobre lo que entiende por “metafísica sistemática”. -

Armstrong.Pdf

EIDE Ê Foundations of Ontology Series Editors Otávio Bueno, Javier Cumpa, John Heil, Peter Simons, Erwin Tegtmeier, Amie L. Thomasson Volume 9 Francesco F. Calemi (Ed.) Metaphysics and Scientic Realism Ê Essays in Honour of David Malet Armstrong Edited by Francesco F. Calemi Copyright-Text ISBN 978-3-11-045461-1 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-045591-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliograe; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston Cover image: Cover-Firma Typesetting: le-tex publishing services GmbH, Leipzig Printing and binding: Druckerei XYZ ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Tuomas E. Tahko Armstrong on Truthmaking and Realism 1 Introduction The title of this paper reects the fact truthmaking is quite frequently considered to be expressive of realism. What this means, exactly, will become clearer in the course of our discussion, but since we are interested in Armstrong’s work on truth- making in particular, it is natural to start from a brief discussion of how truth- making and realism appear to be associated in his work. Armstrong’s interest in truthmaking and the integration of the truthmaker principle to his overall system happened only later in his career, especially in his 1997 book A World of States of Aairs and of course the 2004 Truth and Truthmakers. -

Socrates, Phil Inquiry & the Elenctic Method (F11new)

PLATO, PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY & THE ELENCTIC METHOD All human beings, by their nature, desire understanding. — Aristotle, Metaphysics (Book 1) The safest general characterisation of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. — Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality The elenctic method (part 1): on Meno’s enumerative THE BIG IDEAS TO MASTER definition of (human) virtue • Theory • Socratic humility On Platonic realism & Socratic definitions. According to Plato, a • The elenctic method central part of philosophical inquiry involves an attempt to • Platonic realism understand the Forms. This implies that he is committed the view • Platonic Forms we will call Platonic realism, namely, the view that • Socratic definitions • Essences Platonic realism. The Forms exist. • Natural kinds vs. artefacts • Abstract vs. concrete entities So, according to this theory, Reality contains the Forms. But what • Essential vs. accidental properties are the Forms? That question is best answered as follows. Much of • Counterexample the most important research that philosophers and other scholars do • Reductio ad absurdum argument involves an attempt to answer questions of the form ‘what is x?’ • Sound argument Physicists, for instance, ask ‘what is a black hole?’; biologists ask • Valid argument ‘what is an organism?’; mathematicians ask ‘what is a right triangle?’ • The correspondence theory of truth Let us call the correct answer to a what-is-x question the Socratic • Fact definition of x. We can say, then, that physicists are seeking the Socratic definition of a black hole, biologists investigate the Socratic definition of an organism, and mathematicians look to determine the Socratic definition of a right triangle. -

Leading Ontologists of 19Th and 20Th Centuries

Leading Ontologists of 19th and 20th centuries https://www.ontology.co/idx05.htm Theory and History of Ontology by Raul Corazzon | e-mail: [email protected] INDEX OF THE SECTION: ONTOLOGISTS OF THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES ONTOLOGISTS IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER Bernard Bolzano (1781-1848) Contributions to Logic and Ontology Critical judgments, excerpts from his works, bibliography of critical studies English Translations and Selected Bibliography on the Philosophical Work of Bernard Bolzano: Studies in English (First Part: A - C) Studies in English (Second Part: D - L) Studies in English (Third Part: M - Z) Selected Texts Ausgewählte Werke und Studien in Deutsch Traductions et Essais en Français Traduzioni e Studi in Italiano Franz Brentano (1838-1917) Ontology and His Immanent Realism Excerpts and bibliography of his works, of the English translations and of the most relevant critical studies Franz Brentano: Editions, Translations, Bibliographical Resources and Selected Texts Selected Bibliography on the Philosophical Work of Franz Brentano: Brentano: A - K Brentano: L - Z 1 di 5 09/02/2019, 13:04 Leading Ontologists of 19th and 20th centuries https://www.ontology.co/idx05.htm Charles S. Peirce (1839-1914) Ontology and Semiotics. The Theory of Categories Bibliography of his writings and about his conception of semiotics and the theory of categories Gottlob Frege (1848-1925) Ontology: Being, Existence, and Truth Excerpts from texts, studies and bibliography on his conceptions of being, existence and truth Selected Bibliography on Frege's Ontology -

CHAPTER 1 and Unexemplified Properties, Kinds, and Relations

UNIVERSALS I: METAPHYSICAL REALISM existing objects; whereas other realists believe that there are both exemplified CHAPTER 1 and unexemplified properties, kinds, and relations. The problem of universals I Realism and nominalism The objects we talk and think about can be classified in all kinds of Metaphysical realism ways. We sort things by color, and we have red things, yellow things, and blue things. We sort them by shape, and we have triangular things, circular things, and square things. We sort them by kind, and 0 Realism and nominalism we have elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. The kind of classification The ontology of metaphysical realism at work in these cases is an essential component in our experience of the Realism and predication world. There is little, if anything, that we can think or say, little, if anything, that counts as experience, that does not involve groupings of Realism and abstract reference these kinds. Although almost everyone will concede that some of our 0 Restrictions on realism - exemplification ways of classifying objects reflect our interests, goals, and values, few 0 Further restrictions - defined and undefined predicates will deny that many of our ways of sorting things are fixed by the 0 Are there any unexemplified attributes? objects themselves.' It is not as if we just arbitrarily choose to call some things triangular, others circular, and still others square; they are tri- angular, circular, and square. Likewise, it is not a mere consequence of Overview human thought or language that there are elephants, oak trees, and paramecia. They come that way, and our language and thought reflect The phenomenon of similarity or attribute agreement gives rise to the debate these antecedently given facts about them. -

DAVID MALET ARMSTRONG Ao 1926–2014

26 THE AUSTRALIAN ACADEMY OF THE HUMANITIES ANNUAL REPORT 2013–14 OBITUARIES DAVID MALET ARMSTRONG ao 1926–2014 After a school career that included periods at the Dragon School in Oxford, and at Geelong Grammar, and after a short stint in the navy in the post-war occupation of Japan, he distinguished himself as a student of philosophy in John Anderson’s Department at the University of Sydney. In 1950 he married Madeleine Annette Haydon, a fellow student who was to become a librarian and theatrical critic. Soon after the marriage David was diagnosed with tuberculosis picked up in Japan, so he spent most of that year recuperating in the Concord Repatriation Hospital Having recovered, David went with Madeleine to Oxford, where he undertook the newly established and prestigious BPhil postgraduate degree. On account of his Exeter connection, that became his College, a matter perhaps a little tardily acknowledged by an Honorary Fellowship in 2006. On graduating, David held a temporary post at Birkbeck College in the University of London, and then in 1956 settled in Melbourne, where with great photo: jens maus (damato) [cc by-sa 3.0] via wikimedia commons energy he set about building a reputation and a career at the University of Melbourne, in what was at that avid Armstrong, the doyen of Australian time the premier philosophy department in Australia. Dphilosophers, and the most influential to date His first book,Berkeley’s Theory of Vision, appeared in on the international stage, has died in Sydney at the 1960. The following year he picked up a PhD, almost age of 87. -

Universals.Pdf

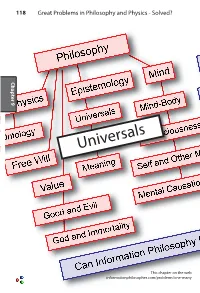

118 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 9 Chapter Universals This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/one-many Universals 119 Universals A “universal” in metaphysics is a property or attribute that is shared by many particular objects (or concepts). It has a subtle relationship to the problem of the one and the many. It is also the question of ontology.1 What exists in the world? Ontology is intimately connected with epistemology - how can we know what exists in the world? Knowledge about objects consists in describing the objects with properties and attributes, including their relations to other objects. Rarely are individual properties unique to an individual object. Although a “bundle of properties” may uniquely charac- 9 Chapter terize a particular individual, most properties are shared with many individuals. The “problem of universals” is the existential status of a given shared property. Does the one universal property exist apart from the many instances in particular objects? Plato thought it does. Aristotle thought it does not. Consider the property having the color red. Is there an abstract concept of redness or “being red?” Granted the idea of a concept of redness, in what way and where in particular does it exist? Nomi- nalists (sometimes called anti-realists) say that it exists only in the particular instances, and that redness is the name of this property. Conceptualists say that the concept of redness exists only in the minds of those persons who have grasped the concept of redness. They might exclude color-blind persons who cannot perceive red. -

A Critical Evaluation of the Epistemology of William Pepperell Montague

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1957 A Critical Evaluation of the Epistemology of William Pepperell Montague John Joseph Monahan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Monahan, John Joseph, "A Critical Evaluation of the Epistemology of William Pepperell Montague " (1957). Master's Theses. 1426. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1957 John Joseph Monahan I"'" A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE EFISTEiv:OLO<1Y OF WILLIAr·~ FEPfF.RELL tJ!ONTAGUE by John Joseph Monahan A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of tre Graduate School , • of Loyola University in Partial Fulfillment of· • the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Janu&.I'1 1957 , , LIFE The Reverend Jol"n J oae ,h r':!)Mran, C. f!. V. was born in Oh .:teago, 1111 [.'018 f r,~arch 2. 1926. He attended Qulgley .Preparatory Se:n.1nary, Oh,1cago t Illino1s, a.nd was gradua.ted from St. Ambrose College, Daven. port, Iowa, August, 1948, with th~ degree of Bacbelor ot Art a • In 1952 he was ordained til prl•• t from St. Thoma. Seminary, Denver, Oolo%'ado tv1 tt; the degree of Haste%' ot Art •• from. -

From Russell to Rawls

A Brief History of Analytic Philosophy A Brief History of Analytic Philosophy From Russell to Rawls By Stephen P. Schwartz A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition first published 2012 © 2012 John Wiley & Sons Inc. Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Stephen P. Schwartz to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.