CHAPTER 1 and Unexemplified Properties, Kinds, and Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Be Realist About in Linguistic Science

What to be realist about in linguistic science Geoffrey K. Pullum School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh This paper was presented at a workshop entitled ‘Foundation of Linguistics: Languages as Abstract Objects’ at the Technische Universitat¨ Carolo-Wilhelmina in Braunschweig, Germany, June 25–28. At the end of his viva, Hilary Putnam asked him, “And tell us, Mr. Boolos, what does the analytical hierarchy have to do with the real world?” Without hesitating Boolos replied, “It’s part of it.” [From the Wikipedia article on the MIT logician George Boolos] Prefatory remarks on realism I need to begin by clarifying what is meant (or at least, what I and others have meant) by ‘realism’. That such clarification is necessary is indicated by the fact that the subtitle of this workshop (‘Lan- guages as Abstract Objects’) clearly pays homage to Katz (1981) (Language and Other Abstract Objects). What the late Jerrold J. Katz meant by the word ‘realism’ does not comport with the usage of most philosophers. Katz shows little interest in defining his terms. He barely even waves a hand in that direc- tion. The third page of Language and Other Abstract Objects book announces that he has had an epiphany: there is “an alternative to both the American structuralists’ and the Chomskian concep- tion of what grammars are theories of, namely, the Platonic realist view that grammars are theories of abstract objects (sentences)” (Katz 1981, 3). Neither ‘Platonic’ nor ‘realist’ are analysed, expli- cated, or even glossed at this point. ‘Platonic realism’ is thereafter abbreviated to ‘Platonism’ and simply assumed to be understood. -

On Moral Understanding

COMMENTTHE COLLEGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE NO 147 | MAY 2003 TOM WHIPPS On Moral Understanding DNA pioneers: The surviving members of the King’s team, who worked on the discovery of the structure of DNA 50 years ago, withDavid James Watson, K Levytheir Cambridge ‘rival’ at the time. From left Ray Gosling, Herbert Wilson, DNA at King’s: DepartmentJames Watson and of Maurice Philosophy Wilkins King’s College the continuing story University of London Prize for his contribution – and A day of celebrations their teams, but also to subse- quent generations of scientists at ver 600 guests attended a cant scientific discovery of the King’s. unique day of events celeb- 20th century,’ in the words of Four Nobel Laureates – Mau- Orating King’s role in the 50th Principal Professor Arthur Lucas, rice Wilkins, James Watson, Sid- anniversary of the discovery of the ‘and their research changed ney Altman and Tim Hunt – double helix structure of DNA on the world’. attended the event which was so 22 April. The day paid tribute not only to oversubscribed that the proceed- Scientists at King’s played a King’s DNA pioneers Rosalind ings were relayed by video link to fundamental role in this momen- Franklin and Maurice Wilkins – tous discovery – ‘the most signifi- who went onto win the Nobel continued on page 2 2 Funding news | 3 Peace Operations Review | 5 Widening participation | 8 25 years of Anglo-French law | 11 Margaret Atwood at King’s | 12 Susan Gibson wins Rosalind Franklin Award | 15 Focus: School of Law | 16 Research news | 18 Books | 19 KCLSU election results | 20 Arts abcdef U N I V E R S I T Y O F L O N D O N A C C O M M O D A T I O N O F F I C E ACCOMMODATION INFORMATION - FINDING SOMEWHERE TO LIVE IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy WARNING: Under no circumstances inshould the this University document be of taken London as providing legal advice. -

Participation and Predication in Plato's Middle Dialogues Author(S): R

Participation and Predication in Plato's Middle Dialogues Author(s): R. E. Allen Source: The Philosophical Review, Vol. 69, No. 2, (Apr., 1960), pp. 147-164 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of Philosophical Review Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2183501 Accessed: 10/08/2008 14:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=duke. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org PARTICIPATION AND PREDICATION IN PLATO'S MIDDLE DIALOGUES* I PROPOSE in this paper to examine three closely related issues in the interpretation of Plato's middle dialogues: the nature of Forms, of participation, and of predication. -

Overturning the Paradigm of Identity with Gilles Deleuze's Differential

A Thesis entitled Difference Over Identity: Overturning the Paradigm of Identity With Gilles Deleuze’s Differential Ontology by Matthew G. Eckel Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy Dr. Ammon Allred, Committee Chair Dr. Benjamin Grazzini, Committee Member Dr. Benjamin Pryor, Committee Member Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2014 An Abstract of Difference Over Identity: Overturning the Paradigm of Identity With Gilles Deleuze’s Differential Ontology by Matthew G. Eckel Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy The University of Toledo May 2014 Taking Gilles Deleuze to be a philosopher who is most concerned with articulating a ‘philosophy of difference’, Deleuze’s thought represents a fundamental shift in the history of philosophy, a shift which asserts ontological difference as independent of any prior ontological identity, even going as far as suggesting that identity is only possible when grounded by difference. Deleuze reconstructs a ‘minor’ history of philosophy, mobilizing thinkers from Spinoza and Nietzsche to Duns Scotus and Bergson, in his attempt to assert that philosophy has always been, underneath its canonical manifestations, a project concerned with ontology, and that ontological difference deserves the kind of philosophical attention, and privilege, which ontological identity has been given since Aristotle. -

Socrates, Phil Inquiry & the Elenctic Method (F11new)

PLATO, PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY & THE ELENCTIC METHOD All human beings, by their nature, desire understanding. — Aristotle, Metaphysics (Book 1) The safest general characterisation of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. — Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality The elenctic method (part 1): on Meno’s enumerative THE BIG IDEAS TO MASTER definition of (human) virtue • Theory • Socratic humility On Platonic realism & Socratic definitions. According to Plato, a • The elenctic method central part of philosophical inquiry involves an attempt to • Platonic realism understand the Forms. This implies that he is committed the view • Platonic Forms we will call Platonic realism, namely, the view that • Socratic definitions • Essences Platonic realism. The Forms exist. • Natural kinds vs. artefacts • Abstract vs. concrete entities So, according to this theory, Reality contains the Forms. But what • Essential vs. accidental properties are the Forms? That question is best answered as follows. Much of • Counterexample the most important research that philosophers and other scholars do • Reductio ad absurdum argument involves an attempt to answer questions of the form ‘what is x?’ • Sound argument Physicists, for instance, ask ‘what is a black hole?’; biologists ask • Valid argument ‘what is an organism?’; mathematicians ask ‘what is a right triangle?’ • The correspondence theory of truth Let us call the correct answer to a what-is-x question the Socratic • Fact definition of x. We can say, then, that physicists are seeking the Socratic definition of a black hole, biologists investigate the Socratic definition of an organism, and mathematicians look to determine the Socratic definition of a right triangle. -

Aristotle on Predication

DOI: 10.1111/ejop.12054 Aristotle on Predication Phil Corkum Abstract: A predicate logic typically has a heterogeneous semantic theory. Sub- jects and predicates have distinct semantic roles: subjects refer; predicates char- acterize. A sentence expresses a truth if the object to which the subject refers is correctly characterized by the predicate. Traditional term logic, by contrast, has a homogeneous theory: both subjects and predicates refer; and a sentence is true if the subject and predicate name one and the same thing. In this paper, I will examine evidence for ascribing to Aristotle the view that subjects and predicates refer. If this is correct, then it seems that Aristotle, like the traditional term logician, problematically conflates predication and identity claims. I will argue that we can ascribe to Aristotle the view that both subjects and predicates refer, while holding that he would deny that a sentence is true just in case the subject and predicate name one and the same thing. In particular, I will argue that Aristotle’s core semantic notion is not identity but the weaker relation of consti- tution. For example, the predication ‘All men are mortal’ expresses a true thought, in Aristotle’s view, just in case the mereological sum of humans is a part of the mereological sum of mortals. A predicate logic typically has a heterogeneous semantic theory. Subjects and predicates have distinct semantic roles: subjects refer; predicates characterize. A sentence expresses a truth if the object to which the subject refers is correctly characterized by the predicate. Traditional term logic, by contrast, has a homo- geneous theory: both subjects and predicates refer; and a sentence is true if the subject and predicate name one and the same thing. -

Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato Philosophical Papers Vol. 30, No. 2 (July 2001): 117-143 Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg Abstract: This paper contrasts the scholastic realists of David Armstrong and Charles Peirce. It is argued that the so-called 'problem of universals' is not a problem in pure ontology (concerning whether universals exist) as Armstrong construes it to be. Rather, it extends to issues concerning which predicates should be applied where, issues which Armstrong sets aside under the label of 'semantics', and which from a Peircean perspective encompass even the fundamentals of scientific methodology. It is argued that Peir ce's scholastic realism not only presents a more nuanced ontology (distinguishing the existent front the real) but also provides more of a sense of why realism should be a position worth fighting for. ... a realist is simply one who knows no more recondite reality than that which is represented in a true representation. C.S. Peirce Like many other philosophical problems, the grandly-named 'Problem of Universals' is difficult to define without begging the question that it raises. Laurence Goldstein, however, provides a helpful hands-off denotation of the problem by noting that it proceeds from what he calls The Trivial Obseruation:2 The observation is the seemingly incontrovertible claim that, 'sometimes some things have something in common'. The 1 Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. Justus Buehler (New York: Dover Publications, 1955), 248. 2 Laurence Goldstein, 'Scientific Scotism – The Emperor's New Trousers or Has Armstrong Made Some Real Strides?', Australasian Journal of Philosophy, vol 61, No. -

The Problem: the Theory of Ideas in Ancient Atomism and Gilles Deleuze

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013 The rP oblem: The Theory of Ideas in Ancient Atomism and Gilles Deleuze Ryan J. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Johnson, R. (2013). The rP oblem: The Theory of Ideas in Ancient Atomism and Gilles Deleuze (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/706 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROBLEM: THE THEORY OF IDEAS IN ANCIENT ATOMISM AND GILLES DELEUZE A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ryan J. Johnson May 2014 Copyright by Ryan J. Johnson 2014 ii THE PROBLEM: THE THEORY OF IDEAS IN ANCIENT ATOMISM AND GILLES DELEUZE By Ryan J. Johnson Approved December 6, 2013 _______________________________ ______________________________ Daniel Selcer, Ph.D Kelly Arenson, Ph.D Associate Professor of Philosophy Assistant Professor of Philosophy (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ______________________________ John Protevi, Ph.D Professor of Philosophy (Committee Member) ______________________________ ______________________________ James Swindal, Ph.D. Ronald Polansky, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College & Graduate Chair, Department of Philosophy School of Liberal Arts Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT THE PROBLEM: THE THEORY OF IDEAS IN ANCIENT ATOMISM AND GILLES DELEUZE By Ryan J. Johnson May 2014 Dissertation supervised by Dr. -

2.2 Glock Et Al

Journal for the History of Book Symposium: Analytical Philosophy Hans-Johann Glock, What is Analytic Philosophy? Volume 2, Number 2 Introduction Hans-Johann Glock..................... 1 Editor in Chief Mark Textor, King’s College London Commentaries Guest Editor Leila Haaparanta......................... 2 Mirja Hartimo, University of Helsinki Christopher Pincock....................6 Editorial Board Panu Raatikainen........................11 Juliet Floyd, Boston University Graham Stevens.......................... 28 Greg Frost-Arnold, Hobart and William Smith Colleges Ryan Hickerson, University of Western Oregon Replies Henry Jackman, York University Hans-Johann Glock..................... 36 Sandra Lapointe, McMaster University Chris Pincock, Ohio State University Richard Zach, University of Calgary Production Editor Ryan Hickerson Editorial Assistant Daniel Harris, CUNY Graduate Center Design Douglas Patterson and Daniel Harris ©2013 The Authors What is Analytic Philosophy? shall not be able to respond to all of the noteworthy criticisms and questions of my commentators. I have divided my responses ac- Hans-Johann Glock cording to commentator rather than topic, while also indicating some connections between their ideas where appropriate. Let me start by thanking the Journal for the History of Analytical Phi- losophy for offering me this opportunity to discuss my book What is Analytical Philosophy? (Cambridge, 2008). I am also very grateful Hans-Johann Glock for the valuable feedback from the contributors. And I thank both University of Zurich the journal and the contributors for their patience in waiting for [email protected] my replies. I was pleased to discover that all of my commentators express a certain sympathy with the central contention of my book, namely that analytic philosophy is an intellectual movement of the twentieth-century (with roots in the nineteenth and offshoots in the twenty-first), held together by family-resemblances on the one hand, ties of historical influence on the other. -

Universals.Pdf

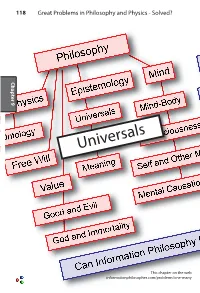

118 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 9 Chapter Universals This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/one-many Universals 119 Universals A “universal” in metaphysics is a property or attribute that is shared by many particular objects (or concepts). It has a subtle relationship to the problem of the one and the many. It is also the question of ontology.1 What exists in the world? Ontology is intimately connected with epistemology - how can we know what exists in the world? Knowledge about objects consists in describing the objects with properties and attributes, including their relations to other objects. Rarely are individual properties unique to an individual object. Although a “bundle of properties” may uniquely charac- 9 Chapter terize a particular individual, most properties are shared with many individuals. The “problem of universals” is the existential status of a given shared property. Does the one universal property exist apart from the many instances in particular objects? Plato thought it does. Aristotle thought it does not. Consider the property having the color red. Is there an abstract concept of redness or “being red?” Granted the idea of a concept of redness, in what way and where in particular does it exist? Nomi- nalists (sometimes called anti-realists) say that it exists only in the particular instances, and that redness is the name of this property. Conceptualists say that the concept of redness exists only in the minds of those persons who have grasped the concept of redness. They might exclude color-blind persons who cannot perceive red. -

How Analytic Philosophy Has Failed Cognitive Science

How Analytic Philosophy Has Failed Cognitive Science Robert Brandom I. Introduction We analytic philosophers have signally failed our colleagues in cognitive science. We have done that by not sharing central lessons about the nature of concepts, concept-use, and conceptual content that have been entrusted to our care and feeding for more than a century. I take it that analytic philosophy began with the birth of the new logic that Gottlob Frege introduced in his seminal 1879 Begriffsschrift. The idea, taken up and championed to begin with by Bertrand Russell, was that the fundamental insights and tools Frege made available there, and developed and deployed through the 1890s, could be applied throughout philosophy to advance our understanding of understanding and of thought in general, by advancing our understanding of concepts—including the particular concepts with which the philosophical tradition had wrestled since its inception. For Frege brought about a revolution not just in logic, but in semantics. He made possible for the first time a mathematical characterization of meaning and conceptual content, and so of the structure of sapience itself. Henceforth it was to be the business of the new movement of analytic philosophy to explore and amplify those ideas, to exploit and apply them wherever they could do the most good. Those ideas are the cultural birthright, heritage, and responsibility of analytic philosophers. But we have not done right by them. For we have failed to communicate some of the most basic of those ideas, failed to explain their significance, failed to make them available in forms usable by those working in allied disciplines who are also professionally concerned to understand the nature of thought, minds, and reason. -

1. Armstrong and Aristotle There Are Two Main Reasons for Not

RECENSIONI&REPORTS report ANNABELLA D’ATRI DAVID MALET ARMSTRONG’S NEO‐ARISTOTELIANISM 1. Armstrong and Aristotle 2. Lowe on Aristotelian substance 3. Armstrong and Lowe on the laws of nature 4. Conclusion ABSTRACT: The aim of this paper is to establish criteria for designating the Systematic Metaphysics of Australian philosopher David Malet Armstrong as neo‐ Aristotelian and to distinguish this form of weak neo‐ Aristotelianism from other forms, specifically from John Lowe’s strong neo‐Aristotelianism. In order to compare the two forms, I will focus on the Aristotelian category of substance, and on the dissimilar attitudes of Armstrong and Lowe with regard to this category. Finally, I will test the impact of the two different metaphysics on the ontological explanation of laws of nature. 1. Armstrong and Aristotle There are two main reasons for not considering Armstrong’s Systematic Metaphysics as Aristotelian: a) the first is a “philological” reason: we don’t have evidence of Armstrong reading and analyzing Aristotle’s main works. On the contrary, we have evidence of Armstrong’s acknowledgments to Peter Anstey1 for drawing his attention to the reference of Aristotle’s theory of truthmaker in Categories and to Jim Franklin2 for a passage in Aristotle’s Metaphysics on the theory of the “one”; b) the second reason is “historiographic”: Armstrong isn’t listed among the authors labeled as contemporary Aristotelian metaphysicians3. Nonetheless, there are also reasons for speaking of Armstrong’s Aristotelianism if, according to 1 D. M. Armstrong, A World of State of Affairs, Cambridge University Press, New York 1978, p. 13. 2 Ibid., p.