Ramla, the Pool of the Arches: New Evidence for the Water Inlet Into the Pool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

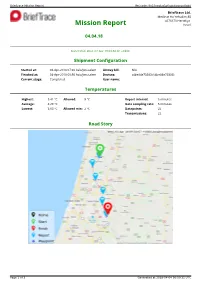

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

Memory Trace Fazal Sheikh

MEMORY TRACE FAZAL SHEIKH 2 3 Front and back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°50 41”N / 35°13 47”E Israeli side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of Neve Yaakov and Beit Ḥanīna. Just beyond the wall lies the neighborhood of al-Ram, now severed from East Jerusalem. Inside front and inside back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°49 10”N / 35°15 59”E Palestinian side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of the Palestinian town of ʿAnata. The Israeli settlement of Pisgat Ze’ev lies beyond in East Jerusalem. This publication takes its point of departure from Fazal Sheikh’s Memory Trace, the first of his three-volume photographic proj- ect on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Published in the spring of 2015, The Erasure Trilogy is divided into three separate vol- umes—Memory Trace, Desert Bloom, and Independence/Nakba. The project seeks to explore the legacies of the Arab–Israeli War of 1948, which resulted in the dispossession and displacement of three quarters of the Palestinian population, in the establishment of the State of Israel, and in the reconfiguration of territorial borders across the region. Elements of these volumes have been exhibited at the Slought Foundation in Philadelphia, Storefront for Art and Architecture, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York, and will now be presented at the Al-Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art in East Jerusalem, and the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah. In addition, historical documents and materials related to the history of Al-’Araqīb, a Bedouin village that has been destroyed and rebuilt more than one hundred times in the ongoing “battle over the Negev,” first presented at the Slought Foundation, will be shown at Al-Ma’mal. -

2009 High School in University! Shachar Jerusalem and Is a Ninth Grader Is Sponsored by at the Menachem the NACOEJ/EDWARD G

Sponsorships Encourage Students to Develop Their Potential Sponsorships give Ethiopian students the chance to gain the most out of school. In some cases, students’ talents become a gift for everyone! The outstanding examples below help us understand how valuable your contributions are. Sara Shachar Zisanu Baruch attends the Dror has a head start on SUMMER 2009 High School in university! Shachar Jerusalem and is a ninth grader is sponsored by at the Menachem THE NACOEJ/EDWARD G. VICTOR HIGH SCHOOL SPONSORSHIP PROGRAM Marsha Croland Begin High School of White Plains, in Ness Ziona. In NY. Sara has just fi fth grade, he took fi nished eleventh a mathematics course by correspondence Sponsors grade and is ac- through the Weizmann Institute for Sci- tive as a counselor in the youth move- ence. Since then, he has been taking ment HaShomer Hatzair, affi liated with special courses in math and science, won Give and the kibbutz movement. Sara has been a fi rst-place in the Municipal Bible contest member of the group since she was nine in sixth grade, and took second-place in years old and was encouraged to become a the Municipal Battlefi eld Heritage Con- Ethiopian counselor by her own counselor last year. test (a quiz on Israeli military history) Sara appreciates the values of teamwork, in seventh grade! Currently, Shachar is in independence, and positive communica- an advanced program for math at Bar Ilan Students tion that she has learned in the move- University and takes math and science ment. As a counselor of fourth graders, courses at Tel Aviv University. -

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 P.M

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. UL 1126 AGENDA 1. Approval of the minutes for November 25, 2003 .................................................... Queener 2. Associate Dean’s Report .......................................................................................... Queener 3. Purdue Dean’s Report ................................................................................................... Story 4. Graduate Office Report ............................................................................................ Queener 5. Committee Business a. Curriculum Subcommittee ........................................................................... O’Palka 6. International Affairs a. IELTS vs. TOEFL ............................................................................................ Allaei 7. Program Approval .................................................................................................... Queener a. M.S. Health Sciences Education – Name Change b. M.A. in Political Science c. M.S. in Music Therapy 8. Discussion ................................................................................................................ Queener a. MSD Thesis Optional b. Joint Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering 9. New Business…………………………………… 10. Next Meeting (February 24) and adjournment Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 Minutes Present: William Bosron, Mark Brenner (co-chair), Ain Haas, Dolores Hoyt, Andrew Hsu, Jane Lambert, Joyce MacKinnon, Jackie O’Palka, Douglas -

Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources

chapter 25 Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources Salim Tamari The Old City of Jerusalem is unique in its predominance of endowed, or waqf, properties (public and family-based). At the end of the twentieth century, waqf properties in all categories totaled 1,781 units, or 54 percent of all proper- ties in the Old City.1 In terms of area, these properties amounted to 348 dunams (1 dunam = 0.247 acres), or about 66 percent of the total area of the Old City. One quarter of those were family endowments (waqf dhirrī), equivalent to 567 units or 84 dunams. The revenue of these endowments was assigned to both private and charitable purposes, which will be explained below. The task of finding accurate sources for interpreting the scope and character of these properties has been a major challenge for the historian. Court records and land registry archives have been plagued with problems of accessibility, shift- ing registration procedures, and proper bureaucratic organization of registered properties. An additional problem was the layers of leasing and subleasing of waqf properties, some of which were never registered. Since 1967, another prob- lem has emerged: the abuse of archaic legal categories of endowments by the State of Israel and its propensity to sequester waqf property on behalf of the state and settler groups. In this chapter I will examine how new archival sources can help to shed light on the extent and nature of these family and public endowments. These archival sources include municipal tax registries for Old City properties, aerial photography and on-site architectural surveys. -

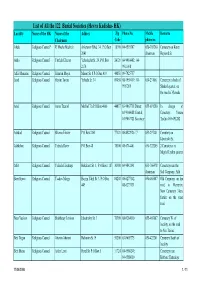

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Israel (Includes West Bank and Gaza) 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

ISRAEL (INCLUDES WEST BANK AND GAZA) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The country’s laws and Supreme Court rulings protect the freedoms of conscience, faith, religion, and worship, regardless of an individual’s religious affiliation. The 1992 Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty describes the country as a “Jewish and democratic state.” The 2018 Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People law determines, according to the government, that “the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people; the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination; and exercising the right to national self- determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish People.” In June, authorities charged Zion Cohen for carrying out attacks on May 17 on religious institutions in Petah Tikva, Ashdod, Tel Aviv, and Kfar Saba. According to his indictment, Cohen sought to stop religious institutions from providing services to secular individuals, thereby furthering his goal of separating religion and the state. He was awaiting trial at year’s end. In July, the Haifa District Court upheld the 2019 conviction and sentencing for incitement of Raed Salah, head of the prohibited Islamic Movement, for speaking publicly in favor an attack by the group in 2017 that killed two police officers at the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount. In his defense, Salah stated that his views were religious opinions rooted in the Quran and that they did not include a direct call to violence. -

Gaza Strip West Bank

Afula MAP 3: Land Swap Option 3 Zububa Umm Rummana Al-Fahm Mt. Gilboa Land Swap: Israeli to Palestinian At-Tayba Silat Al-Harithiya Al Jalama Anin Arrana Beit Shean Land Swap: Palestinian to Israeli Faqqu’a Al-Yamun Umm Hinanit Kafr Dan Israeli settlements Shaked Al-Qutuf Barta’a Rechan Al-Araqa Ash-Sharqiya Jenin Jalbun Deir Abu Da’if Palestinian communities Birqin 6 Ya’bad Kufeirit East Jerusalem Qaffin Al-Mughayyir A Chermesh Mevo No Man’s Land Nazlat Isa Dotan Qabatiya Baqa Arraba Ash-Sharqiya 1967 Green Line Raba Misiliya Az-Zababida Zeita Seida Fahma Kafr Ra’i Illar Mechola Barrier completed Attil Ajja Sanur Aqqaba Shadmot Barrier under construction B Deir Meithalun Mechola Al-Ghusun Tayasir Al-Judeida Bal’a Siris Israeli tunnel/Palestinian Jaba Tubas Nur Shams Silat overland route Camp Adh-Dhahr Al-Fandaqumiya Dhinnaba Anabta Bizzariya Tulkarem Burqa El-Far’a Kafr Yasid Camp Highway al-Labad Beit Imrin Far’un Avne Enav Ramin Wadi Al-Far’a Tammun Chefetz Primary road Sabastiya Talluza Beit Lid Shavei Shomron Al-Badhan Tayibe Asira Chemdat Deir Sharaf Roi Sources: See copyright page. Ash-Shamaliya Bekaot Salit Beit Iba Elon Moreh Tire Ein Beit El-Ma Azmut Kafr Camp Kafr Qaddum Deir Al-Hatab Jammal Kedumim Nablus Jit Sarra Askar Salim Camp Chamra Hajja Tell Balata Tzufim Jayyus Bracha Camp Beit Dajan Immatin Kafr Qallil Rujeib 2 Burin Qalqiliya Jinsafut Asira Al Qibliya Beit Furik Argaman Alfe Azzun Karne Shomron Yitzhar Itamar Mechora Menashe Awarta Habla Maale Shomron Immanuel Urif Al-Jiftlik Nofim Kafr Thulth Huwwara 3 Yakir Einabus -

A Long School Day and Mothers' Labor Supply

Research Department Bank of Israel A Long School Day and Mothers' Labor Supply Gal Yeshurun* Discussion Paper No. 2012.08 June 2012 _____________________________________ Bank of Israel, http://www.boi.gov.il * Gal Yeshurun' Research Department – E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Phone: 972-2-6552621 The study was undertaken under the close supervision of Noam Zussman. I would like to thank Haggay Etkes for his considerable assistance, and Ella Shachar, Nahum Blass, and the participants in the Bank of Israel's Research Department Seminar. Thanks also to Yigal Duchan and Hagit Meir for their help in placing the Ministry of Education files at my disposal and for information on the implementation of the long school day, and to Mark Feldman for his assistance in obtaining the Labor Force Survey (MUC) files. Any views expressed in the Discussion Paper Series are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Israel 91007 —– 780 "“ –— ,– º “ Research Department, Bank of Israel, POB 780, 91007 Jerusalem, Israel “º — º º – –— – “ ! º “ º “ º —º – º º “ º—º – … “ “–… ,–…º “ º “–º “ º “ – º “ º , . –º º — º º º— ,“ “–ºº ººº “ —º “ – º .–— ! “ , … … “ ! º # … ººº # –— … –… “ – — , —“º “ — “– “…º º “–º º –— ! !º .“º — º º .“ “º — “ —º º º “ — $ º ,“ … “ , º º “ º — “““—ºº A long school day and mothers' labor supply Gal Yeshurun Abstract The availability and low cost of childcare arrangements for young children generally have a significant positive effect on the labor supply of parents. However, empirical evidence related to lengthening the school day, within an obligatory and fully subsidized framework, is sparse, and not found in Israel. -

A Section of the Gezer–Ramla Aqueduct (Qanat Bint Al-Kafir) and a Mamluk-Period Cemetery Near Moshav Yashresh

‘Atiqot 79, 2014 A SECTION OF THE GEZER–RAMLA AQUEDUCT (QANAT BINT AL-KAFIR) AND A MAMLUK-PERIOD CEMETERY NEAR MOSHAV YasHRESH AMIR GORZALCZANY INTRODUCTION Umayyad-period aqueduct between Gezer and Ramla (Fig. 1; Gorzalczany 2011). In For the past sixty years, archaeologists and July and August 2006, a further segment of farmers have been exposing sections of the this aqueduct was uncovered during salvage 186 000 188 000 192 000 194 000 190 000 to Tel Aviv 80 1. Kaplan and Gophna 1950 (see Zelinger and Shmueli 2002:281, Fig. 2) Ramla White 2. Zelinger and Shmueli 2002 Mosque 70 3. Gorzalczany 2011 4. Toueg 2010 648 5. Tsion-Cinamon 2005 648 000 6. Zelinger 2000 000 7. Zelinger and Shmueli 2002 Area A 8. Zelinger and Shmueli 2002 (cemetery) 9. Zelinger 2001 10 11 10. The Excavation Area B 70 11. Tal and Taxel 2008; Gorzalczany 2006; 2008a; 2008d 9 80 Yashresh Mazliah 646 90 646 000 90 000 Road 40 The Aqueduct ovot h to Re 80 8 90 644 100 7 644 000 90 000 6 5 4 3 Na‘an 2 100 110 642 130 642 000 000 Petahya 1 140 to Be’er Sheva‘ Tel Gezer 180 0 2 210 km 192 000 186 000 190 000 188 000 Fig. 1. Location map showing the current excavation areas (10; Areas A, B), the reconstructed course of the aqueduct, the cemetery, and previous excavations and surveys. 214 AMIR GORZALCZANY L105 Area A L110 IV L108 L109 L111 L107 L112 III Area B II m 10.5 I 0 15 m Plan 1.