The Arab Palestinians in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

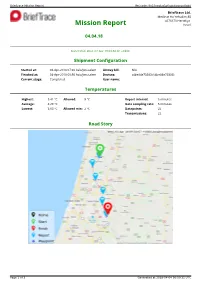

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Staring Back at the Sun: Video Art from Israel, 1970-2012 an Exhibition and Public Program Touring Internationally, 2016-2017

Staring Back at the Sun: Video Art from Israel, 1970-2012 An Exhibition and Public Program Touring Internationally, 2016-2017 Roee Rosen, still from Confessions Coming Soon, 2007, video. 8:40 minutes. Video, possibly more than any other form of communication, has shaped the world in radical ways over the past half century. It has also changed contemporary art on a global scale. Its dual “life” as an agent of mass communication and an artistic medium is especially intertwined in Israel, where artists have been using video artistically in response to its use in mass media and to the harsh reality video mediates on a daily basis. The country’s relatively sudden exposure to commercial television in the 1990s coincided with the Palestinian uprising, or Intifada, and major shifts in internal politics. Artists responded to this in what can now be considered a “renaissance” of video art, with roots traced back to the ’70s. An examination of these pieces, many that have rarely been presented outside Israel, as well as recent, iconic works from the past two decades offers valuable lessons on how art and culture are shaped by larger forces. Staring Back at the Sun: Video Art from Israel, 1970-2012 traces the development of contemporary video practice in Israel and highlights work by artists who take an incisive, critical perspective towards the cultural and political landscape in Israel and beyond. Showcasing 35 works, this program includes documentation of early performances, films and videos, many of which have never been presented outside of Israel until now. Informed by the international 1 history of video art, the program surveys the development of the medium in Israel and explores how artists have employed technology and material to examine the unavoidable and messy overlap of art and politics. -

2009 High School in University! Shachar Jerusalem and Is a Ninth Grader Is Sponsored by at the Menachem the NACOEJ/EDWARD G

Sponsorships Encourage Students to Develop Their Potential Sponsorships give Ethiopian students the chance to gain the most out of school. In some cases, students’ talents become a gift for everyone! The outstanding examples below help us understand how valuable your contributions are. Sara Shachar Zisanu Baruch attends the Dror has a head start on SUMMER 2009 High School in university! Shachar Jerusalem and is a ninth grader is sponsored by at the Menachem THE NACOEJ/EDWARD G. VICTOR HIGH SCHOOL SPONSORSHIP PROGRAM Marsha Croland Begin High School of White Plains, in Ness Ziona. In NY. Sara has just fi fth grade, he took fi nished eleventh a mathematics course by correspondence Sponsors grade and is ac- through the Weizmann Institute for Sci- tive as a counselor in the youth move- ence. Since then, he has been taking ment HaShomer Hatzair, affi liated with special courses in math and science, won Give and the kibbutz movement. Sara has been a fi rst-place in the Municipal Bible contest member of the group since she was nine in sixth grade, and took second-place in years old and was encouraged to become a the Municipal Battlefi eld Heritage Con- Ethiopian counselor by her own counselor last year. test (a quiz on Israeli military history) Sara appreciates the values of teamwork, in seventh grade! Currently, Shachar is in independence, and positive communica- an advanced program for math at Bar Ilan Students tion that she has learned in the move- University and takes math and science ment. As a counselor of fourth graders, courses at Tel Aviv University. -

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 P.M

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. UL 1126 AGENDA 1. Approval of the minutes for November 25, 2003 .................................................... Queener 2. Associate Dean’s Report .......................................................................................... Queener 3. Purdue Dean’s Report ................................................................................................... Story 4. Graduate Office Report ............................................................................................ Queener 5. Committee Business a. Curriculum Subcommittee ........................................................................... O’Palka 6. International Affairs a. IELTS vs. TOEFL ............................................................................................ Allaei 7. Program Approval .................................................................................................... Queener a. M.S. Health Sciences Education – Name Change b. M.A. in Political Science c. M.S. in Music Therapy 8. Discussion ................................................................................................................ Queener a. MSD Thesis Optional b. Joint Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering 9. New Business…………………………………… 10. Next Meeting (February 24) and adjournment Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 Minutes Present: William Bosron, Mark Brenner (co-chair), Ain Haas, Dolores Hoyt, Andrew Hsu, Jane Lambert, Joyce MacKinnon, Jackie O’Palka, Douglas -

Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources

chapter 25 Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources Salim Tamari The Old City of Jerusalem is unique in its predominance of endowed, or waqf, properties (public and family-based). At the end of the twentieth century, waqf properties in all categories totaled 1,781 units, or 54 percent of all proper- ties in the Old City.1 In terms of area, these properties amounted to 348 dunams (1 dunam = 0.247 acres), or about 66 percent of the total area of the Old City. One quarter of those were family endowments (waqf dhirrī), equivalent to 567 units or 84 dunams. The revenue of these endowments was assigned to both private and charitable purposes, which will be explained below. The task of finding accurate sources for interpreting the scope and character of these properties has been a major challenge for the historian. Court records and land registry archives have been plagued with problems of accessibility, shift- ing registration procedures, and proper bureaucratic organization of registered properties. An additional problem was the layers of leasing and subleasing of waqf properties, some of which were never registered. Since 1967, another prob- lem has emerged: the abuse of archaic legal categories of endowments by the State of Israel and its propensity to sequester waqf property on behalf of the state and settler groups. In this chapter I will examine how new archival sources can help to shed light on the extent and nature of these family and public endowments. These archival sources include municipal tax registries for Old City properties, aerial photography and on-site architectural surveys. -

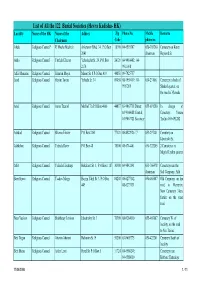

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israel (Includes West Bank and Gaza) 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

ISRAEL (INCLUDES WEST BANK AND GAZA) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The country’s laws and Supreme Court rulings protect the freedoms of conscience, faith, religion, and worship, regardless of an individual’s religious affiliation. The 1992 Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty describes the country as a “Jewish and democratic state.” The 2018 Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People law determines, according to the government, that “the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people; the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination; and exercising the right to national self- determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish People.” In June, authorities charged Zion Cohen for carrying out attacks on May 17 on religious institutions in Petah Tikva, Ashdod, Tel Aviv, and Kfar Saba. According to his indictment, Cohen sought to stop religious institutions from providing services to secular individuals, thereby furthering his goal of separating religion and the state. He was awaiting trial at year’s end. In July, the Haifa District Court upheld the 2019 conviction and sentencing for incitement of Raed Salah, head of the prohibited Islamic Movement, for speaking publicly in favor an attack by the group in 2017 that killed two police officers at the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount. In his defense, Salah stated that his views were religious opinions rooted in the Quran and that they did not include a direct call to violence. -

Existence to Shared Society: a Paradigm Shift in Intercommunity Peacebuilding Among Jews and Arabs in Israel Ran Kuttner 1,2

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research From Co-existence to Shared Society: A Paradigm Shift in Intercommunity Peacebuilding Among Jews and Arabs in Israel Ran Kuttner 1,2 1 Peace and Conflict Management Studies, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel 2 Academic Advisor, Givat Haviva, Menashe, Israel Keywords Abstract shared society, dialogue, relational peacebuilding. The discourse regarding Jewish–Arab intercommunity peacebuilding pro- cesses is undergoing major changes in recent years, gradually shifting Correspondence from “coexistence” as the desired outcome to “shared society.” This arti- Ran Kuttner, Peace and Conflict cle suggests that this transition portrays a paradigm shift that should be Management Studies, University acknowledged and taken into account by peacebuilding activists and con- of Haifa, Haifa, Israel; e-mail: flict specialists. The first section describes various common understand- [email protected]. ings of this shift in the context of Jewish-Arab relations in Israel. [Correction added on 4 August Section two will describe the underpinnings of the paradigm shift from 2017, after first online publica- individualistic to relational understanding of the self and argue that this tion: Other author affiliation has shift is consistent with the wish for transition to “shared society” and to been added.] develop more dialogic frameworks of groups’ shared living. Section three will present a case study, the work of Givat Haviva, emphasizing the rela- tional premises that can be found in its methodology to cultivate a shared society among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Transitions: From Coexistence to Shared Society in Israeli Peacebuilding Efforts The discourse regarding Jewish–Arab intercommunity peacebuilding processes is undergoing major changes in recent years, gradually shifting from “coexistence” as the desired outcome to “shared society.” This shift derives from a disappointment in the vision of coexistence, realizing that this is a thin, unsatis- factory vision of a cohesive society (Salomon & Issawi, 2009). -

The Events in Qalansawe and Umm Al Hiran

Inter-Agency Task Force on Israeli Arab Issues Home Demolitions and State-Minority Relations: The Events in Qalansawe and Umm Al Hiran January 2017 In mid-January, two highly publicized demolitions of homes took place in the Arab localities of Qalansawe and Umm Al Hiran in Israel, resulting in the tragic deaths of one Israeli police officer and one Arab Bedouin teacher. The confrontations ignited Arab protests and two general strikes and have brought tensions around land and housing, some of the most sensitive issues between the state and its Arab minority, to a head. The following update briefly summarizes the sequence of events, the questions they have raised related to the government frameworks for resolving land and planning issues, and the broader context contributing to heightened tensions. Qalansawe On January 10th, 11 homes were demolished in Qalansawe, (a Muslim city of 22,000 inhabitants, located 20 minutes east of Netanya), marking the largest such demolition outside of the Negev in many years. The event drew widespread indignation from Israel’s Arab society and led the mayor of Qalansawe, Abed El Bassat Salameh, to resign in protest. The Higher Follow Up Committee (a non-governmental body representing Arab society in Israel) called a one-day general strike and a 10,000-strong protest was held in Qalansawe on Friday, January 13th. The Qalansawe homes, built on private land, were designated as illegal because they were built without permits and on land zoned for agricultural use. This is a common issue in Arab localities because most do not have detailed urban development plans approved by State authorities, nor land reserves on which to construct new homes and neighborhoods.