The Events in Qalansawe and Umm Al Hiran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Existence to Shared Society: a Paradigm Shift in Intercommunity Peacebuilding Among Jews and Arabs in Israel Ran Kuttner 1,2

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research From Co-existence to Shared Society: A Paradigm Shift in Intercommunity Peacebuilding Among Jews and Arabs in Israel Ran Kuttner 1,2 1 Peace and Conflict Management Studies, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel 2 Academic Advisor, Givat Haviva, Menashe, Israel Keywords Abstract shared society, dialogue, relational peacebuilding. The discourse regarding Jewish–Arab intercommunity peacebuilding pro- cesses is undergoing major changes in recent years, gradually shifting Correspondence from “coexistence” as the desired outcome to “shared society.” This arti- Ran Kuttner, Peace and Conflict cle suggests that this transition portrays a paradigm shift that should be Management Studies, University acknowledged and taken into account by peacebuilding activists and con- of Haifa, Haifa, Israel; e-mail: flict specialists. The first section describes various common understand- [email protected]. ings of this shift in the context of Jewish-Arab relations in Israel. [Correction added on 4 August Section two will describe the underpinnings of the paradigm shift from 2017, after first online publica- individualistic to relational understanding of the self and argue that this tion: Other author affiliation has shift is consistent with the wish for transition to “shared society” and to been added.] develop more dialogic frameworks of groups’ shared living. Section three will present a case study, the work of Givat Haviva, emphasizing the rela- tional premises that can be found in its methodology to cultivate a shared society among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Transitions: From Coexistence to Shared Society in Israeli Peacebuilding Efforts The discourse regarding Jewish–Arab intercommunity peacebuilding processes is undergoing major changes in recent years, gradually shifting from “coexistence” as the desired outcome to “shared society.” This shift derives from a disappointment in the vision of coexistence, realizing that this is a thin, unsatis- factory vision of a cohesive society (Salomon & Issawi, 2009). -

A Long School Day and Mothers' Labor Supply

Research Department Bank of Israel A Long School Day and Mothers' Labor Supply Gal Yeshurun* Discussion Paper No. 2012.08 June 2012 _____________________________________ Bank of Israel, http://www.boi.gov.il * Gal Yeshurun' Research Department – E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Phone: 972-2-6552621 The study was undertaken under the close supervision of Noam Zussman. I would like to thank Haggay Etkes for his considerable assistance, and Ella Shachar, Nahum Blass, and the participants in the Bank of Israel's Research Department Seminar. Thanks also to Yigal Duchan and Hagit Meir for their help in placing the Ministry of Education files at my disposal and for information on the implementation of the long school day, and to Mark Feldman for his assistance in obtaining the Labor Force Survey (MUC) files. Any views expressed in the Discussion Paper Series are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Israel 91007 —– 780 "“ –— ,– º “ Research Department, Bank of Israel, POB 780, 91007 Jerusalem, Israel “º — º º – –— – “ ! º “ º “ º —º – º º “ º—º – … “ “–… ,–…º “ º “–º “ º “ – º “ º , . –º º — º º º— ,“ “–ºº ººº “ —º “ – º .–— ! “ , … … “ ! º # … ººº # –— … –… “ – — , —“º “ — “– “…º º “–º º –— ! !º .“º — º º .“ “º — “ —º º º “ — $ º ,“ … “ , º º “ º — “““—ºº A long school day and mothers' labor supply Gal Yeshurun Abstract The availability and low cost of childcare arrangements for young children generally have a significant positive effect on the labor supply of parents. However, empirical evidence related to lengthening the school day, within an obligatory and fully subsidized framework, is sparse, and not found in Israel. -

Imagining the Border

A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: President Barack Obama watches as Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in New York, September 2009. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) Map CREDITS Israeli settlements in the Triangle Area and the West Bank: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, 2008, and 2009 data Palestinian communities in the West Bank: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 data Jerusalem neighborhoods: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2008 data Various map elements (Green Line, No Man’s Land, Old City, Jerusalem municipal bounds, fences, roads): Dan Rothem, S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace Cartography: International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City, MD Contents About the Authors / v Acknowledgments / vii Settlements and Swaps: Envisioning an Israeli-Palestinian Border / 1 Three Land Swap Scenarios / 7 Maps 1. -

Back to Basics: Israel's Arab Minority and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

BACK TO BASICS: ISRAEL’S ARAB MINORITY AND THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT Middle East Report N°119 – 14 March 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. PALESTINIAN CITIZENS SINCE THE SECOND INTIFADA: GROWING ALIENATION ................................................................................................................... 1 A. OCTOBER 2000: THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL ................................................................................... 1 B. SEEKING REGIONAL AND GLOBAL SUPPORT ................................................................................ 5 C. POLITICAL BACKLASH ................................................................................................................. 8 II. POLITICAL TRENDS AMONG PALESTINIANS IN ISRAEL ............................... 10 A. BOYCOTTING THE POLITICAL SYSTEM ....................................................................................... 10 B. THE ISLAMIC MOVEMENT .......................................................................................................... 12 C. THE SECULAR PARTIES .............................................................................................................. 15 D. FILLING THE VACUUM: EXTRA-PARLIAMENTARY ORGANISATIONS ........................................... 19 E. CONFRONTATION LINES ............................................................................................................. 22 III. PALESTINIANS IN ISRAEL AND THE PEACE PROCESS -

West Bank Area Is 6,195 Km2 (Includes Shomron Northwest Portion of Dead Sea, One-Half of No Man's Land, and All of 3 East Jerusalem Except Mount Scopus)

Israeli to Palestinian See “Map 5a: Afula Area* Km2 % of Baseline† Triangle Detail” A North 18.7 .30% B Northwest 2.2 .04% C Southwest 25.1 .40% Umm Mt. Gilboa D South 13.3 .21% Al-Fahm E Gaza 87.6 1.41% Kafr Qara H Beit Shean F Chalutzah not included not included G Southwest 2 not included not included Umm Jenin H Triangle 146.2 2.36% Al-Qutuf TOTAL‡ 293.1 4.73 % A Palestinian to Israeli H % of Settler % of Total Bloc Km2 Baseline† Population** Settlers 1 North of Ariel 31.0 .50% 11,621 3.89% 2 Ariel 29.6 .48% 19,737 6.60% 3 Western Edge/ 105.3 1.70% 79,687 26.65% B Modiin Illit†† 4 Expanded Ofra/Bet El 26.1 .42% 20,023 6.70% Tulkarem 5 North of Jerusalem 10.9 .18% 15,866 5.31% Qalansawe 6 East Jerusalem 29.1 .47% not included not included Jewish neighborhoods Tayibe 7 Maale Adumim 10.8 .17% 34,600 11.57% H Kfar Adumim 5.8 .09% 2,800 .94% 8 Betar Illit/Gush Etzion 42.8 .69% 54,012 18.06% Tire Kedumim Nablus 9 Southern Edge 1.7 .03% 900 .30% TOTAL‡ 293.1 4.73% 239,246‡‡ 80.01%*** Qalqiliya 1 * Areas considered unpopulated. Alfe Karne Menashe Immanuel † Baseline figure for total Gaza/West Bank area is 6,195 km2 (includes Shomron northwest portion of Dead Sea, one-half of No Man's Land, and all of 3 east Jerusalem except Mount Scopus). ‡ Totals derived from rounding decimal numbers. -

List of Cities of Israel

Population Area SNo Common name District Mayor (2009) (km2) 1 Acre North 46,300 13.533 Shimon Lancry 2 Afula North 40,500 26.909 Avi Elkabetz 3 Arad South 23,400 93.140 Tali Ploskov Judea & Samaria 4 Ariel 17,600 14.677 Eliyahu Shaviro (West Bank) 5 Ashdod South 206,400 47.242 Yehiel Lasri 6 Ashkelon South 111,900 47.788 Benny Vaknin 7 Baqa-Jatt Haifa 34,300 16.392 Yitzhak Veled 8 Bat Yam Tel Aviv 130,000 8.167 Shlomo Lahiani 9 Beersheba South 197,300 52.903 Rubik Danilovich 10 Beit She'an North 16,900 7.330 Jacky Levi 11 Beit Shemesh Jerusalem 77,100 34.259 Moshe Abutbul Judea & Samaria 12 Beitar Illit 35,000 6.801 Meir Rubenstein (West Bank) 13 Bnei Brak Tel Aviv 154,400 7.088 Ya'akov Asher 14 Dimona South 32,400 29.877 Meir Cohen 15 Eilat South 47,400 84.789 Meir Yitzhak Halevi 16 El'ad Center 36,300 2.756 Yitzhak Idan 17 Giv'atayim Tel Aviv 53,000 3.246 Ran Kunik 18 Giv'at Shmuel Center 21,800 2.579 Yossi Brodny 19 Hadera Haifa 80,200 49.359 Haim Avitan 20 Haifa Haifa 265,600 63.666 Yona Yahav 21 Herzliya Tel Aviv 87,000 21.585 Yehonatan Yassur 22 Hod HaSharon Center 47,200 21.585 Hai Adiv 23 Holon Tel Aviv 184,700 18.927 Moti Sasson 24 Jerusalem Jerusalem 815,600 125.156 Nir Barkat 25 Karmiel North 44,100 19.188 Adi Eldar 26 Kafr Qasim Center 18,800 8.745 Sami Issa 27 Kfar Saba Center 83,600 14.169 Yehuda Ben-Hemo 28 Kiryat Ata Haifa 50,700 16.706 Ya'akov Peretz 29 Kiryat Bialik Haifa 37,300 8.178 Eli Dokursky 30 Kiryat Gat South 47,400 16.302 Aviram Dahari 31 Kiryat Malakhi South 20,600 4.632 Motti Malka 32 Kiryat Motzkin Haifa -

The Palestinian Minority in Israel

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT POLICY BRIEFING Shackled at home: The Palestinian minority in Israel Abstract More than one in five Israeli citizens is Palestinian — 'Arab' according to Israeli administrative terminology. A minority in their homeland, these Palestinians face ever- widening forms of discrimination. Many Israeli Jews and their politicians advocate revoking the Palestinian minority's basic civil and political rights. Those who perceive Palestinians as a threat to the Jewish nature of the Israeli state increasingly support the idea of transferring Palestinians out of the country. More than 30 Israeli laws effectively penalise the minority, and new ones are currently being introduced. For Israeli Palestinians, the implications are severe and unremitting. Not only does the minority suffer from higher unemployment and poverty rates than their Jewish counterparts, but Palestinian towns are poor and lack adequate infrastructure. Whilst the international community and the EU have expressed concern about specific discriminatory legal acts in Israel, actions are now needed. The EU should establish a policy-oriented approach consistent with its values of democracy and respect for human rights — fundamental elements of the Association Agreement between the EU and Israel. DG EXPO/B/PolDep/Note/2012_ 210 September 2012 PE 491.440 EN Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This Policy Briefing is an initiative of the Policy Department, DG EXPO. AUTHORS: Dua' NAKHALA (under the supervision of Pekka HAKALA) Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union Policy Department WIB 06 M 71 rue Wiertz 60 B-1047 Brussels Feedback to [email protected] is welcome. -

Dictionary of Palestinian Political Terms

Dictionary of Palestinian Political Terms PASSIA Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, Jerusalem PASSIA, the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, is an Arab, non-profit Palestinian institution with a financially and legally indepen- dent status. It is not affiliated with any government, political party or organization. PASSIA seeks to present the Question of Palestine in its national, Arab and interna- tional contexts through academic research, dialogue and publication. PASSIA endeavors that research undertaken under its auspices be specialized, scientific and objective and that its symposia and workshops, whether interna- tional or intra-Palestinian, be open, self-critical and conducted in a spirit of har- mony and cooperation. Copyright PASSIA 3rd updated and revised edition, December 2019 ISBN: 978-9950-305-52-6 PASSIA Publication 2019 Tel.: 02-6264426 | Fax: 02-6282819 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.passia.org PO Box 19545, Jerusalem Contents Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………………………. i Foreword …………………………………………………………………….….…………..……………. iii Dictionary A-Z ………………………………………………………………………….………………. 1 Main References Cited…………………………………………..……………………………… 199 Abbreviations ACRI Association for Civil Rights in PCBS Palestinian Central Bureau of Israel Statistics AD Anno Domini PFLP Popular Front for the Liberation AIPAC American Israel Public Affairs of Palestine Committee PFLP-GC Popular Front for the Liberation ALF Arab Liberation Front of Palestine – General ANM -

The Arab Palestinians in Israel

Housing Transformation within Urbanized Communities: The Arab Palestinians in Israel Rassem Khamaisi* University of Haifa This paper discusses the residential transformation process within the Arab Pales- tinian community in Israel as a result of urbanization. It highlights the variety of housing models applicable to sub-groups of the Arab population according to geographical distribution, ethno-religious affiliation, and type of locality where different urbanization trends and social and physical rural environments are key characteristics. The most common residential model for this population group is the self-built house. The self-built house is common for upper-middle class Israeli Jews, while it remains the model of choice of lower-middle class Arab Israelis. This paper also considers the critical changes and processes of housing supply and demand as a result of the urbanization process, examining the planning, social and political factors, as well as the obstacles that have a direct impact on the Arab housing market. Keywords: Urbanization, Arabs, Israel, urban village, latent urbanization, self- built housing. Arab Palestinian (henceforth Arab) localities and communities in Israel have changed dramatically in recent decades. They have shifted from the small traditional-village type communities to a more modern hybrid rural-urban type, that is, an “urbanized village,” through a process that is both general and unique to their environmental circumstances (Khamaisi, 2012). This urbanization process has led to incremental changes in physical, socio-economic, and socio-cultural environments within Arab communities and in turn has affected the behavioral patterns of Arab residents. The physical and environmental characteristics of the Arab housing market con- stitute a major factor in differentiating rural and urban localities. -

Urban Planning in Israel's Arab Communities

Inter-Agency Task Force on Israeli Arab Issues Urban Planning in Israel’s Arab Communities Essential and Complex Challenge for Economic and Residential Development February 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 1 AN ECOMOMIC DEVELOPMENT PRIORITY ........................................................................................ 2 PLANNING BARRIERS FOR ARAB MUNICIPALITIES ............................................................................ 3 Israel’s Planning Processes ......................................................................................................... 3 Unique Characteristics and Challenges in Arab Localities .......................................................... 4 GROWING GOVERNMENT FOCUS ..................................................................................................... 7 Development Approach: 120 Days Committee to GR-922 ......................................................... 7 Rule of Law and Enforcement Focus......................................................................................... 10 SECTION II: IMPLEMENTATION STATUS AND BARRIERS ........................................................... 12 CURRENT STATUS ........................................................................................................................... -

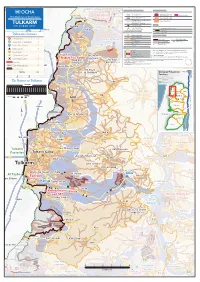

Tulkarm TULKARM

¹º» !P !P At Tarem ?B65 P!!P Khirbet al Muntar Tura !P !P !P Khirbet al MuntarClosed and Restricted Areas Arab alIsraeli Settlements al Gharbiya !P ash Sharqiya Nazlat ash !P Israeli military base Hamdun Settlement built-up , outer Access is prohibited Settlement Outpost B?6 Reikhan Umm Dar !P limit andSheikh municipal area Zeid West Bank Access Restrictions IsraeliAl closed Khuljan military area Land cultivated by settlers Dhaher al 'Abed Access is prohibited Barta'a Existing and projected 'closed areas' % GF Israeli Nature Reserve !P !P Zabda behind the Barrier Adebal GF %¹º» !P !P !P Qeiqis Access is limited to permit holders Ya'bad TULKARMSha'ar Menashe Tunnel/Underpass* Roads Kufeirit OCTOBER 2017 Akkaba !T # P! Observation Tower* !P Al Manshiya !P Prohibited Palestinian vehicle use !P ") * Not counted in the total closure figures. Meiser Khirbet Mas'ud Main road % Palestinian Communities Ya'bad # Other road Tulkarem Closures Governorate Capital Mevo Dotan % ## # West Bank Barrier ImreihaGovernorate Boundry Checkpoints 5 Qaffin !P % ¹º» !P Khirbet Fraseen Built-up %Constructed Planned Re-routing !P Green Line Checkpoints 2 < 1000 Residents Under Construction Barrier Gate GF Khirbet1000 al - 10,000 Mkahhal EG % !P Planned Route Partial Checkpoints 2 Fraseen % > 10,000 Jabal al Aqra'a !P Occupied Palestinian!P Oslo Interim Agreements (1995-1999)Maoz Zvi Earthmounds 9 585 B? 1 Area ATerritory 1. Extensive delegation of powers to the PalestinianL E AuthorityB A N O N Roadblocks - !P Area B2 2. Partial delegation of powers to the Palestinian Authority; joint Khirbet al-Hamaam Israeli-Palestinian security coordination GF Special Case (H2)3 Nazlat 'Isa 3.