Urban Planning in Israel's Arab Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

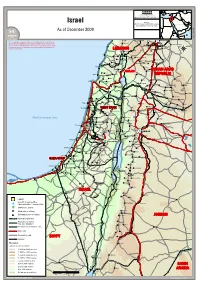

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Focuspoint International 866-340-8569 861 SW 78Th Avenue, Suite B200 [email protected] Plantation, FL 33324 SUMMARY NN02

INFOCUS QUARTERLY SUMMARY TERRORISM & CONFLICT, NATURAL DISASTERS AND CIVIL UNREST Q2 2021 FocusPoint International 866-340-8569 861 SW 78th Avenue, Suite B200 [email protected] Plantation, FL 33324 www.focuspointintl.com SUMMARY NN02 NATURAL DISASTERS Any event or force of nature that has cyclone, hurricane, tornado, tsunami, volcanic catastrophic consequences and causes eruption, or other similar natural events that give damage or the potential to cause a crisis to a rise to a crisis if noted and agreed by CAP customer. This includes an avalanche, FocusPoint. landslide, earth quake, flood, forest or bush fire, NUMBER OF INCIDENTS 32 3 3 118 20 9 Asia Pacific 118 Sub-Saharan Africa 20 Middle East and North Africa 3 Europe 32 Domestic United States and Canada 3 Latin America 9 MOST "SIGNIFICANT" EVENTS • Indonesia: Tropical Cyclone Seroja • Canada: Deaths in connection with • DRC: Mt. Nyiragongo eruption an ongoing heatwave • Algeria: Flash Floods • Panama: Floods/Landslides • Russia: Crimea and Krasnodar Krai flooding 03 TERRORISM / CONFLICT Terrorism means an act, including but not government(s), committed for political, limited to the use of force or violence and/or the religious, ideological or similar purposes threat thereof, of any person or group(s) of including the intention to influence any persons, whether acting alone or on behalf of or government and/or to put the public, or any in connection with any organization(s) or section of the public, in fear. NUMBER OF INCIDENTS 20 1 270 209 144 15 Asia Pacific 209 Sub-Saharan Africa 144 Middle East and North Africa 270 Europe 20 Domestic United States and Canada 1 Latin America 15 MOST "SIGNIFICANT" EVENTS • Taliban Attack on Ghazni • Tigray Market Airstrike • Solhan Massacre • Landmine Explosion 04 POLITICAL THREAT / CIVIL UNREST The threat of action designed to influence the purposes of this travel assistance plan, a government or an international governmental political threat is extended to mean civil threats organization or to intimidate the public, or a caused by riots, strikes, or civil commotion. -

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Schechter@35: Living Judaism 4

“The critical approach, the honest and straightforward study, the intimate atmosphere... that is Schechter.” Itzik Biton “The defining experience is that of being in a place where pluralism “What did Schechter isn't talked about: it's lived.” give me? The ability Liti Golan to read the most beautiful book in the world... in a different way.” Yosef Peleg “The exposure to all kinds of people and a variety of Jewish sources allowed for personal growth and the desire to engage with ideas and people “As a daughter of immigrants different than me.” from Libya, earning this degree is Sigal Aloni a way to connect to the Jewish values that guided my parents, which I am obliged to pass on to my children and grandchildren.” Schechter@35: Tikva Guetta Living Judaism “I acquired Annual Report 2018-2019 a significant and deep foundation in Halakhah and Midrash thanks to the best teachers in the field.” Raanan Malek “When it came to Jewish subjects, I felt like an alien, lost in a foreign city. At Schechter, I fell into a nurturing hothouse, leaving the barren behind, blossoming anew.” Dana Stavi The Schechter Institutes, Inc. • The Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, the largest M.A. program in is a not for profit 501(c)(3) Jewish Studies in Israel with 400 students and 1756 graduates. organization dedicated to the • The Schechter Rabbinical Seminary is the international rabbinical school advancement of pluralistic of Masorti Judaism, serving Israel, Europe and the Americas. Jewish education. The Schechter Institutes, Inc. provides support • The TALI Education Fund offers a pluralistic Jewish studies program to to four non-profit organizations 65,000 children in over 300 Israeli secular public schools and kindergartens. -

West Nile Virus (WNV) Activity in Humans and Mosquitos

West Nile virus (WNV) activity in humans and mosquitos Updated for 28/11/2016 In the following report, a human case patient who is defined as "suspected" refers to a patient whose lab test results indicate a possibility of infection with WNV, and a human case patient who is defined as "confirmed" refers to a patient whose lab test results show a definite infection with WNV. The final definition status of a patient who initially was diagnosed as "suspected" may be changed to "confirmed" due to additional lab test results that were obtained over time. Cumulative numbers of human case patients and mosquitos positive for WNV by location: Until the 28/11/2016, human cases with WNF have been identified in 54 localities and WNV infected mosquitos were found in 6 localities. אגף לאפידמיולוגיה Division of Epidemiology משרד הבריאות Ministry of Health ת.ד.1176 ירושלים P.O.B 1176 Jerusalem [email protected] [email protected] טל: 02-5080522 פקס: Tel: 972-2-5080522 Fax: 972-2-5655950 02-5655950 Table showing WNV in human by place of residency: Date sample Diagnostic status Locality No. Locality Health district received in lab according to lab 1 Or Yehuda 31/05/2016 Suspected Tel Aviv Or Yehuda 02/06/2016 Suspected Tel Aviv 2 Or Aqiva 17/07/2016 Suspected Hadera 3 Ashdod 19/09/2016 Suspected Ashqelon Ashdod 27/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon 4 Ashqelon 29/08/2016 Suspected Ashqelon Ashqelon 05/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 08/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 13/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 22/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon -

Hand in Hand Hand in Hand Integrated Education in Israel, Annual Creating a Better Future Re for Both Jews & Arabs Po R T

Annual Report 2018-19 1 يدًا بيد יד ביד Hand in Hand Hand in Hand Integrated Education in Israel, Annual Creating a Better Future Re for Both Jews & Arabs po r t 2 0 1 8 - 1 9 2 Our Children “Deserve to Grow Up Not Being Afraid of Each Other ” Annual Report 2018-19 3 يدًا بيد יד ביד Hand in Hand Hand in Hand Israel’s Only Network of Integrated Schools for Jews & Arabs 1,950 Students 6 Locations Across Israel Pre-K through 12 Thousands of Impacted Families 4 Message from Our CEO Dear Friends, Last winter, we held a retreat that brought teachers, alumni, staff, and active parents together for the first time. It was an exhilarating event encapsulating what Hand in Hand is all about - bringing up the next generation, impacting society, building community, and institutionalizing equality. I was especially touched to hear the following words spoken by Sarah Sheikh, a Hand in Hand graduate, who shared: “The Hand in Hand education wired our brains differently – I am wired to assume that there will always be more than one angle to an issue, and I have the ability, for the rest of my life, to listen – even when it’s something that’s difficult to hear.” More than anything, the past year has been about growing. We operated six Hand in Hand schools with 1,835 students and community work reaching some 10,000 people. We laid the groundwork to build a seventh community and school, this time in Nazareth Illit. Our talented educators have been creating new multicultural syllabi, standardizing curricula teaching Arabic as a second language, and developing platforms to share Hand in Hand principles and learning with schools across the country. -

SMALL TOWNS, BIG Opportunities

feature by RACHMIEL DAYKIN SMALL TOWNS, BIGImpressions oPpORTUNITIES from an out-of-town kehillos tour of IMMANUEL, AFULA, HAR YONA and CARMIEL Photos by Sruli Glausiusz The Immanuel tour was directed by Eliezer Biller, community askan and developer. Har Yona-Belz and Toldos Avraham Yitzchak apartments and mosdos chinuch, including a Litvish cheder. NEWSMAGAZINE November 18, 2020 12 SMALL TOWNS, BIG oPpORTUNITIES Carmiel – Matan Nachliel shul. Givat HaMoreh – Kollel in the Ohel Moshe shul. 2 Kislev 5781 NEWSMAGAZINE 13 hen chareidi Jews from English-speaking countries settle in Eretz Yisrael, they tend to do so in the areas familiar to them, where there are relatively high concentrations of like-minded people speaking their native language. This has given rise to a “pale of settlement,” as it were, where one finds many English-speakers and sometimes even bubble-like American communities. This pale of settlement, for lack of a better name, has Yerushalayim at its center, and stretches out to Ramat Beit Shemesh, Kiryat Ye’arim (Telshe Stone), Modi’in Ilit and Beitar Ilit, each of which Wis within a half-hour drive from Yerushalayim. People who live there may visit Tzfas and Meron, weddings and other events may take them to Bnei Brak, but by and large, the community of English-speaking olim has been keeping to its familiar turf — Yerushalayim and its satellite chareidi towns. However, housing prices went up drastically over the past two decades, and many people can no longer afford to buy a house or apartment within the Yerushalayim orbit. Will this force many English-speaking olim to give up on their dream of settling in Eretz Yisrael? Since the high prices are a challenge to Israeli chareidim as well, a tour was recent- ly conducted by a group of Anglos (as English-speakers living in Eretz Yisrael are sometimes referred to), each serving as representatives for larger groups, to see how Israelis are coping. -

KAFR KANNA (JEBEL KHUWWEIKHA): IRON II, LATE HELLENISTIC and ROMAN REMAINS a Salvage Excavation Was Carried out in November 20

Hadashot Arkeologiyot— Excavations ans Surveys in Israel 125 KAFR KANNA (JEBEL KHUWWEIKHA): IRON II, LATE HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN REMAINS YARDENNA ALEXANDRE INTRODUCTION A salvage excavation was carried out in November 2006 prior to construction on the lower western slope of Jebel Khuwweikha (‘the weak’ or ‘perforated’ hill), a soft, chalky limestone hill rising to the east of the village nucleus of Kafr Kanna in the Lower Galilee (map ref. NIG 232700/739025, OIG 182700/239025; hilltop elevation 350 m asl; Fig. 1:a).1 The site, at an altitude of c. 300 m asl, afforded some protection, although not qualifying as a naturally fortified spot. The moderate slopes were amenable to olive and fruit cultivation, as well as to goat and sheep grazing, whilst fertile agricultural lands were accessible c. 1 km to the north, in the Tur‘an/Bet Rimon Valley. This valley was traversed by the ancient east–west road connecting ‘Akko and Tiberias. The nearest fresh water source, a spring (known as “Kanna spring”), is found south of the village nucleus, about 900 m southeast of, and 80 m lower than, the site (at c. 220 m asl), rendering water carrying a tedious chore. The present-day Jebel Khuwweikha senior inhabitants recall the women’s daily trek to the spring to bring water. The local nari and chalky limestone are well suited for quarrying building stones and cutting out rock-hewn agricultural installations and caves. Several surveys and salvage excavations have been carried out over the past twenty years in the village of Kafr Kanna, which sprawls over several hills (Fig. -

Adalah's 2006 Annual Report of Activities

ADALAH’S 2006 ANNUAL REPORT OF ACTIVITIES Issued May 2007 Introduction This report highlights Adalah’s key activities in 2006, our tenth-year anniversary. As this report reflects, in 2006 Adalah undertook a wide range of legal representations and conducted numerous other advocacy and educational initiatives of crucial importance in promoting and defending the rights of Palestinian citizens of Israel. Adalah (“Justice” in Arabic) is an independent human rights organization, registered in Israel. It is a non-profit, non-governmental, and non-partisan legal center. Established in November 1996, it serves Arab citizens of Israel, numbering over one million people or close to 20% of the population. Adalah works to protect human rights in general and the rights of the Arab minority in particular. Adalah’s main goals are to achieve equal individual and collective rights for the Arab minority in Israel in different fields including land rights; civil and political rights; cultural, social, and economic and rights; religious rights; women’s rights; and prisoners’ rights. Adalah is the leading Arab-run NGO that utilizes “legal measures,” such as litigating cases before the Israeli courts and appealing to governmental authorities based on legal standards and analysis to secure rights for Palestinian citizens of Israel. Adalah intensively addresses issues of discrimination against Palestinian citizens of Israel as a group, as a national minority, and speaks from a minority perspective in its legal interventions. In order to achieve these goals, Adalah: brings cases before Israeli courts and various state authorities; advocates for legislation; provides legal consultation to individuals, non-governmental organizations, and Arab institutions; appeals to international institutions and forums; organizes study days, seminars, and workshops, and publishes reports on legal issues concerning the rights of the Arab minority in particular, and human rights in general; and trains stagaires (legal apprentices), law students, and new lawyers in the field of human rights. -

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories Shadow Report Submitted by Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights Response to the State of Israel’s Report to the United Nations Regarding the Implementation of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights September 2014 Written by Atty. Sharon Karni-Kohn Edited by Elana Silver and Ma'ayan Turner Contributions by Cesar Yeudkin, Nili Baruch, Sari Kronish, Nir Shalev, Alon Cohen Lifshitz Translated from Hebrew by Jessica Bonn 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….…5 Response to Pars. 44-48 in the State Report: Territorial Application of the Covenant………………………………………………………………………………5 Question 6a: Demolition of Illegal Construstions………………………………...5 Response to Pars. 57-59 in the State Report: House Demolition in the Bedouin Population…………………………………………………………………………....5 Response to Pars. 60-62 in the State Report: House Demolition in East Jerusalem…7 Question 6b: Planning in the Arab Localities…………………………………….8 Response to Pars. 64-77 in the State Report: Outline Plans in Arab Localities in Israel, Infrastructure and Industrial Zones…………………………………………………8 Response to Pars. 78-80 in the State Report: The Eastern Neighborhoods of Jerusalem……………………………………………………………………………10 Question 6c: State of the Unrecognized Bedouin Villages, Means for Halting House Demolitions and Proposed Law for Reaching an Arrangement for Bedouin Localities in the Negev, 2012…………………………………………...15 Response to Pars. 81-88 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population……….…15 Response to Pars. 89-93 in the State Report: Goldberg Commission…………….19 Response to Pars. 94-103 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population in the Negev – Government Decisions 3707 and 3708…………………………………………….19 Response to Par.