Commuting Patterns in Israel 1991-2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTICLES Israel's Migration Balance

ARTICLES Israel’s Migration Balance Demography, Politics, and Ideology Ian S. Lustick Abstract: As a state founded on Jewish immigration and the absorp- tion of immigration, what are the ideological and political implications for Israel of a zero or negative migration balance? By closely examining data on immigration and emigration, trends with regard to the migration balance are established. This article pays particular attention to the ways in which Israelis from different political perspectives have portrayed the question of the migration balance and to the relationship between a declining migration balance and the re-emergence of the “demographic problem” as a political, cultural, and psychological reality of enormous resonance for Jewish Israelis. Conclusions are drawn about the relation- ship between Israel’s anxious re-engagement with the demographic problem and its responses to Iran’s nuclear program, the unintended con- sequences of encouraging programs of “flexible aliyah,” and the intense debate over the conversion of non-Jewish non-Arab Israelis. KEYWORDS: aliyah, demographic problem, emigration, immigration, Israel, migration balance, yeridah, Zionism Changing Approaches to Aliyah and Yeridah Aliyah, the migration of Jews to Israel from their previous homes in the diaspora, was the central plank and raison d’être of classical Zionism. Every stream of Zionist ideology has emphasized the return of Jews to what is declared as their once and future homeland. Every Zionist political party; every institution of the Zionist movement; every Israeli government; and most Israeli political parties, from 1948 to the present, have given pride of place to their commitments to aliyah and immigrant absorption. For example, the official list of ten “policy guidelines” of Israel’s 32nd Israel Studies Review, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 2011: 33–65 © Association for Israel Studies doi: 10.3167/isr.2011.260108 34 | Ian S. -

Reducing Revisions in Israel's House Price Index with Nowcasting Models

Ottawa Group, Rio de Janeiro, 2019 16th Meeting of the Ottawa Group International Working Group on Price Indices Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8-10 May 2019 Reducing Revisions in Israel’s House Price Index with Nowcasting Models1 Doron Sayaga,b, Dano Ben-hura and Danny Pfeffermanna,c,d a b Central Bureau of Statistics, Israel Bar-Ilan University, Israel c d Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel University of Southampton, UK Abstract National Statistical Offices must balance between the timeliness and the accuracy of the indicators they publish. Due to late-reported transactions of sold houses, many countries, including Israel, publish a provisional House Price Index (HPI), which is subject to revisions as further transactions are recorded. Until 2018, the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS) published provisional HPIs based solely on the known reported transactions, which suffered from large revisions. In this paper we propose a novel method for minimizing the size of the revisions. Noting that the late-reported transactions behave differently from the on-time reported transactions, three types of variables are predicted monthly at the sub-district level as input data for a nowcasting model: (1) the average characteristics of the late-reported transactions; (2) the average price of the late-reported transactions; and (3) the number of late-reported transactions. These three types of variables are predicted separately, based on models fitted to data from previous months. Evaluation of our model shows a reduction in the magnitude of the revisions by more than 50%. The model is now used by the ICBS for the official publication of the provisional HPIs at both the national and district levels. -

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

Map of Amazya (109) Volume 1, the Northern Sector

MAP OF AMAZYA (109) VOLUME 1, THE NORTHERN SECTOR 1* 2* ISRAEL ANTIQUITIES AUTHORITY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ISRAEL MAP OF AMAZYA (109) VOLUME 1, THE NORTHERN SECTOR YEHUDA DAGAN 3* Archaeological Survey of Israel Publications of the Israel Antiquities Authority Editor-in-Chief: Zvi Gal Series editor: Lori Lender Volume editor: DaphnaTuval-Marx English editor: Lori Lender English translation: Don Glick Cover: ‘Baqa‘ esh Shamaliya’, where the Judean Shephelah meets the hillcountry (photograph: Yehuda Dagan) Typesetting, layout and production: Margalit Hayosh Preparation of illustrations: Natalia Zak, Elizabeth Belashov Printing: Keterpress Enterprises, Jerusalem Copyright © The Israel Antiquities Authority The Archaeological Survey of Israel Jerusalem, 2006 ISBN 965–406–195–3 www.antiquities.org.il 4* Contents Editors’ Foreword 7* Preface 8* Introduction 9* Index of Site Names 51* Index of Sites Listed by Period 59* List of Illustrations 65* The Sites—the Northern Sector 71* References 265* Maps of Periods and Installations 285* Hebrew Text 1–288 5* 6* Editors’ Foreword The Map of Amazya (Sheet 10–14, Old Israel Grid; sheet 20–19, New Israel Grid), scale 1:20,000, is recorded as Paragraph 109 in Reshumot—Yalqut Ha-Pirsumim No. 1091 (1964). In 1972–1973 a systematic archaeological survey of the map area was conducted by a team headed by Yehuda Dagan, on behalf of the Archaeological Survey of Israel and the Israel Antiquities Authority (formerly the Department of Antiquities and Museums). Compilation of Material A file for each site in the Survey archives includes a detailed report by the survey team members, plans, photographs and a register of the finds kept in the Authority’s stores. -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

Tel Aviv-Jaffa

Chapter 7 Tel Aviv-Jaffa 1 Introduction Tel Aviv-Jaffa is the second city of Israel, located on the Mediterranean coast- line. It is the nation’s financial center and technology hub; it is also the third- largest urban economy in the Middle East after Abu Dhabi and Kuwait City (Brookings Institution 2014). The city receives around three million tourists and visitors annually. It has been a long way since Tel Aviv was founded in 1909 by a few dozens of Jewish immigrants on the outskirts of the ancient port city of Jaffa, then mostly populated by Arabs. The first neighborhoods had been established in 1886 (Elkayam 1990) and new quarters made their appearance outside Jaffa in the following years. On 11 April 1909, 66 Jewish families gathered on a sand dune to parcel out the land. This was the official date of the establishment of Tel Aviv. By 1914, Tel Aviv had grown to more than one square kilometer. The town rapidly became an attraction for newcomers. These were the years of the British Mandate and the number of those immigrants – from Poland and Ger- many mainly – increased all along the 1930s, propelled by the world economic crisis of 1929 and the rise to power of Nazism in Germany in 1993. As a conse- quence, frictions intensified between Arabs and Jews in Palestine1 but did little to prevent Tel Aviv from growing (Glass 2002). In 1923, Tel Aviv was the first town to be wired to electricity in the country, and it was granted municipal status in 1934. By 1937 it had grown to 150,000 inhabitants, compared to Jaffa’s 69,000 residents. -

2009 High School in University! Shachar Jerusalem and Is a Ninth Grader Is Sponsored by at the Menachem the NACOEJ/EDWARD G

Sponsorships Encourage Students to Develop Their Potential Sponsorships give Ethiopian students the chance to gain the most out of school. In some cases, students’ talents become a gift for everyone! The outstanding examples below help us understand how valuable your contributions are. Sara Shachar Zisanu Baruch attends the Dror has a head start on SUMMER 2009 High School in university! Shachar Jerusalem and is a ninth grader is sponsored by at the Menachem THE NACOEJ/EDWARD G. VICTOR HIGH SCHOOL SPONSORSHIP PROGRAM Marsha Croland Begin High School of White Plains, in Ness Ziona. In NY. Sara has just fi fth grade, he took fi nished eleventh a mathematics course by correspondence Sponsors grade and is ac- through the Weizmann Institute for Sci- tive as a counselor in the youth move- ence. Since then, he has been taking ment HaShomer Hatzair, affi liated with special courses in math and science, won Give and the kibbutz movement. Sara has been a fi rst-place in the Municipal Bible contest member of the group since she was nine in sixth grade, and took second-place in years old and was encouraged to become a the Municipal Battlefi eld Heritage Con- Ethiopian counselor by her own counselor last year. test (a quiz on Israeli military history) Sara appreciates the values of teamwork, in seventh grade! Currently, Shachar is in independence, and positive communica- an advanced program for math at Bar Ilan Students tion that she has learned in the move- University and takes math and science ment. As a counselor of fourth graders, courses at Tel Aviv University. -

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 P.M

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. UL 1126 AGENDA 1. Approval of the minutes for November 25, 2003 .................................................... Queener 2. Associate Dean’s Report .......................................................................................... Queener 3. Purdue Dean’s Report ................................................................................................... Story 4. Graduate Office Report ............................................................................................ Queener 5. Committee Business a. Curriculum Subcommittee ........................................................................... O’Palka 6. International Affairs a. IELTS vs. TOEFL ............................................................................................ Allaei 7. Program Approval .................................................................................................... Queener a. M.S. Health Sciences Education – Name Change b. M.A. in Political Science c. M.S. in Music Therapy 8. Discussion ................................................................................................................ Queener a. MSD Thesis Optional b. Joint Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering 9. New Business…………………………………… 10. Next Meeting (February 24) and adjournment Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 Minutes Present: William Bosron, Mark Brenner (co-chair), Ain Haas, Dolores Hoyt, Andrew Hsu, Jane Lambert, Joyce MacKinnon, Jackie O’Palka, Douglas -

Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources

chapter 25 Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources Salim Tamari The Old City of Jerusalem is unique in its predominance of endowed, or waqf, properties (public and family-based). At the end of the twentieth century, waqf properties in all categories totaled 1,781 units, or 54 percent of all proper- ties in the Old City.1 In terms of area, these properties amounted to 348 dunams (1 dunam = 0.247 acres), or about 66 percent of the total area of the Old City. One quarter of those were family endowments (waqf dhirrī), equivalent to 567 units or 84 dunams. The revenue of these endowments was assigned to both private and charitable purposes, which will be explained below. The task of finding accurate sources for interpreting the scope and character of these properties has been a major challenge for the historian. Court records and land registry archives have been plagued with problems of accessibility, shift- ing registration procedures, and proper bureaucratic organization of registered properties. An additional problem was the layers of leasing and subleasing of waqf properties, some of which were never registered. Since 1967, another prob- lem has emerged: the abuse of archaic legal categories of endowments by the State of Israel and its propensity to sequester waqf property on behalf of the state and settler groups. In this chapter I will examine how new archival sources can help to shed light on the extent and nature of these family and public endowments. These archival sources include municipal tax registries for Old City properties, aerial photography and on-site architectural surveys. -

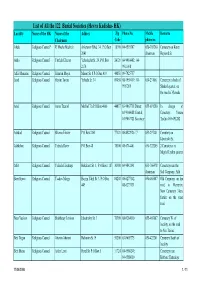

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

ISRAEL Population R-Pihe POPULATION of the State of Israel at the End of June 1954 Was 1,687,886

ISRAEL Population r-piHE POPULATION of the State of Israel at the end of June 1954 was 1,687,886. J. Of these, 188,936 (about 11 per cent) were non-Jews. The table below shows the growth of the population of Israel since May 1948. TABLE 1 JEWISH POPULATION OF ISRAEL, MAY 1948-JULY 1954 Tear Jews Non-Jews Total 1948 758,000 1949 1,013,000 160,000 1,173,000 1950 1,203,000 167,000 1,370,000 1951 1,404,000 173,000 1,577,000 1952 1,450,000 179,000 1,629,000 1953 1,483,505 185,892 1,669,397 1954 (July) 1,498,950 188,936 1,687,886 The total yearly population increase fell from 17 per cent in 1950 to 15 per cent in 1951, 3.3 per cent in 1952, and 2.3 per cent in 1953, due to a decrease in the number of immigrants. Since the first half of 1952 the natural increase had exceeded the net migration. During the first half of 1953 the number of emigrants exceeded the number of immigrants, but during the latter half of the year, immigration was again somewhat greater than emi- gration. During 1953 there were 11,800 immigrants and 8,650 emigrants in all. During the first six months of 1954, 4,128 new immigrants came to Israel. TABLE 2 GROWTH OF JEWISH POPULATION IN ISRAEL (in thousands) 1954 Year 1949 1950 1951 1952 7953 (Jan.-March) Net migration 235 160 167 10 2 4 Natural increase 20 29 35 35 35 9.5 TOTAL INCREASE 255 189 202 45 37 10.5 466 ISRAEL 467 VITAL STATISTICS The net birth rate (the number of live births per 1,000 residents) was 30.8 during the first months of 1954, as compared with 32 in 1953 and 33 in 1952. -

20141116 Herzliya ME WMD Report

Pugwash Workshop on “The Unchangeable Middle East” Herzliya, Israel 14-15 November 2014 MAIN POINTS: • The ISIS/Daesh threat has emerged as the most serious threat to regional stability given its penetration into Iraq and Syria. Although it does not explicitly focus on Israel, as it now stands there is concern as it nears the northern border of Israel. • The extremism of the ISIS/Daesh movement has perversely weakened the perceived extremism of other radical movements in the Middle East such as Hizbollah and Hamas. • Although it appears that a deal on the Iran nuclear issue is close, there is still significant difference over what constitutes a good deal from Israeli perspectives; concern persists over breakout, possible military dimensions to Iran’s past nuclear activities, and verification. However, there is the risk of torpedoing a reasonable deal on these grounds. • The ramifications of a deal on the Iranian nuclear issue include a possible regional problem of technological proliferation in other states, as well as concerns over emboldening Iran to act through proxies vis-à-vis Israel. On the flipside, it was pointed out a deal could help bring Iran on board with action to be taken against Daesh. • Some consider that the major threat to Israel today has become the decline of Israel’s status in international public opinion, particularly in the wake of the most recent Gaza war. • There has been a predominant Israeli narrative that has been sold very well, and it is continued today, that there is no partner for peace on the Palestinian side. • The Israeli-Palestinian peace process does not really exist at this time, and the prospects for it being reinvigorated are slim.