An Imaginary Conversation with Clint Eastwood's Dirty Harry—Toward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clint Eastwood Et Les Années 1980 Julien Fonfrède

Document generated on 09/28/2021 9:57 a.m. 24 images Papy fait de la résistance Clint Eastwood et les années 1980 Julien Fonfrède Années 1980 – Laboratoire d’un cinéma populaire Number 183, August–September 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/85996ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Fonfrède, J. (2017). Papy fait de la résistance : Clint Eastwood et les années 1980. 24 images, (183), 31–31. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Années 1980 – Laboratoire d’un cinéma populaire PAPY FAIT DE LA RÉSISTANCE CLINT EASTWOOD ET LES ANNÉES 1980 par Julien Fonfrède es réalisateurs, acteurs et actrices phares D des décennies précédant les années 1980, nombreux sont ceux et celles qui sont tombés dans l’oubli au cours de cette période. Le cinéma rajeunit alors. Une nouvelle génération de réali- sateurs, de spectateurs, de sujets et de visages débarque. Difficile, pour beaucoup, de s’adapter aux changements. Pour Clint Eastwood, ce ne sera en revanche pas le cas. -

Thf SO~Twarf Toolworks®Catalog SOFTWARE for FUN & INFORMATION

THf SO~TWARf TOOlWORKS®CATAlOG SOFTWARE FOR FUN & INFORMATION ORDER TOLL FREE 1•800•234•3088 moni tors each lesson and builds a seri es of personalized exercises just fo r yo u. And by THE MIRACLE PAGE 2 borrowi ng the fun of vid eo ga mes, it Expand yo ur repertoire ! IT'S AMIRAClf ! makes kids (even grown-up kids) want to The JI!/ irac/e So11g PAGE 4 NINT!NDO THE MIRACLE PIANO TEACHING SYSTEM learn . It doesn't matter whether you 're 6 Coflectioll: Vo/11111e I ~ or 96 - The Mirttcle brings th e joy of music adds 40 popular ENT!RTA INMENT PAGE/ to everyo ne. ,.-~.--. titles to your The Miracle PiC1110 PRODUCTI VITY PAGE 10 Tet1dti11gSyste111, in cluding: "La Bamba," by Ri chi e Valens; INFORMATION PAGElJ "Sara," by Stevie Nicks; and "Thi s Masquerade," by Leon Russell. Volume II VA LU EP ACKS PAGE 16 adds 40 MORE titles, including: "Eleanor Rigby," by John Lennon and Paul McCartney; "Faith," by George M ichael; Learn at your own pace, and at "The Girl Is M in e," by Michael Jackson; your own level. THESE SYMBOLS INDICATE and "People Get Ready," by C urtis FORMAT AVAILABILITY: As a stand-alone instrument, The M irt1de Mayfield. Each song includes two levels of play - and learn - at yo ur own rivals the music industry's most sophis playin g difficulty and is full y arra nged pace, at your own level, NIN TEN DO ti cated MIDI consoles, with over 128 with complete accompaniments for a truly ENTERTAINMENT SYST!M whenever yo u want. -

Ant CARTOLINA 12Luglio 150X

Bologna, Sotto dal 4 luglio al 1° settembre le stelle Piazza Maggiore e BarcArena del Cinema ore 21.30 molte coscienze, trasformando il film in terreno di scontro. La stroncatura Domenica 12 luglio 2020 più celebre, dell’influentissima Pauline Kael, bollava senza mezzi termini Dirty Harry come apologia del fascismo. [...] Serata promossa da L’infuocato dibattito ideologico attorno al film si comprende meglio se in- serito nel clima dell’epoca, segnato da rivolte studentesche, cultura hippy sulla cresta dell’onda, guerra in Vietnam vicina allo sfascio: Ispettore Cal- Polizieschi urbani laghan emerge come oggetto scomodo, in cui si afferma il desiderio di un punto fermo virile e forcaiolo in mezzo alle incertezze sociali. Al tempo ISPETTORE CALLAGHAN: stesso, la figura di Callaghan si staglia come angelo della vendetta fuori IL CASO SCORPIO È TUO dalla storia, attraversato da pulsioni di morte eterne e universali. Il detecti- ve di Eastwood, insomma, sembra trarre forza dal convergere di un alone (Dirty Harry, USA/1971) mitizzante e di un tratteggio realistico preciso, in un’oscillazione che con- tribuisce ad arricchire la complessa riflessione sulla violenza che altri film, Regia: Don Siegel. Soggetto: Harry Julian Fink, Rita M. Fink. Sceneggiatura: nello stesso 1971, stanno intraprendendo: Il braccio violento della legge di Harry Julian Fink, Rita M. Fink, Dean Riesner. Fotografia: Bruce Surtees. William Friedkin, Cane di paglia e Arancia meccanica. Ispettore Callaghan, Montaggio: Carl Pingitore. Scenografia: Dale Hennesy. Musica: Lalo in particolare, insiste sulla dimensione urbana del fenomeno. Schifrin. Interpreti: Clint Eastwood (Harry Callahan), Harry Guardino Ferme restando le posizioni etiche dei vari commentatori, quasi tutti si (Bressler), Andy Robinson (Scorpio), Reni Santoni (Chico Sanchez), John sono trovati d’accordo sulla potenza visiva e narrativa del film, tra gli esiti Vernon (il sindaco), John Larch (il capo della polizia), John Mitchum più alti di un regista che ha sempre fatto dell’efficacia una virtù stilistica. -

1-Abdul Haseeb Ansari

Journal of Criminal Justice and Law Review : Vol. 1 • No. 1 • June 2009 IDENTIFYING LARGE REPLICABLE FILM POPULATIONS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE FILM RESEARCH: A UNIFIED FILM POPULATION IDENTIFICATION METHODOLOGY FRANKLIN T. WILSON Indiana State University ABSTRACT: Historically, a dominant proportion of academic studies of social science issues in theatrically released films have focused on issues surrounding crime and the criminal justice system. Additionally, a dominant proportion has utilized non-probability sampling methods in identifying the films to be analyzed. Arguably one of the primary reasons film studies of social science issues have used non-probability samples may be that no one has established definitive operational definitions of populations of films, let alone develop datasets from which researchers can draw. In this article a new methodology for establishing film populations for both qualitative and quantitative research–the Unified Film Population Identification Methodology–is both described and demonstrated. This methodology was created and is presented here in hopes of expand the types of film studies utilized in the examination of social science issues to those communication theories that require the examination of large blocks of media. Further, it is anticipated that this methodology will help unify film studies of social science issues in the future and, as a result, increase the reliability, validity, and replicability of the said studies. Keywords: UFPIM, Film, Core Cop, Methodology, probability. Mass media research conducted in the academic realm has generally been theoretical in nature, utilizing public data, with research agendas emanating from the academic researchers themselves. Academic studies cover a gambit of areas including, but not limited to, antisocial and prosocial effects of specific media content, uses and gratifications, agenda setting by the media, and the cultivation of perceptions of social reality (Wimmer & Dominick, 2003). -

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This List Was Created to Make It Easier for Customers to Figure out What Type of NVRAM They Need for Each Machine

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This list was created to make it easier for customers to figure out what type of NVRAM they need for each machine. Please consult the product pages at www.pinitech.com for each type of NVRAM for further information on difficulty of installation, any jumper changes necessary on your board(s), a diagram showing location of the RAM being replaced & more. *NOTE: This list is meant as quick reference only. On Williams WPC and Sega/Stern Whitestar games you should check the RAM currently in your machine since either a 6264 or 62256 may have been used from the factory. On Williams System 11 games you should check that the chip at U25 is 24-pin (6116). See additional diagrams & notes at http://www.pinitech.com/products/cat_memory.php for assistance in locating the RAM on your board(s). PLUG-AND-PLAY (NO SOLDERING) Games below already have an IC socket installed on the boards from the factory and are as easy as removing the old RAM and installing the NVRAM (then resetting scores/settings per the manual). • BALLY 6803 → 6116 NVRAM • SEGA/STERN WHITESTAR → 6264 OR 62256 NVRAM (check IC at U212, see website) • DATA EAST → 6264 NVRAM (except Laser War) • CLASSIC BALLY → 5101 NVRAM • CLASSIC STERN → 5101 NVRAM (later Stern MPU-200 games use MPU-200 NVRAM) • ZACCARIA GENERATION 1 → 5101 NVRAM **NOT** PLUG-AND-PLAY (SOLDERING REQUIRED) The games below did not have an IC socket installed on the boards. This means the existing RAM needs to be removed from the board & an IC socket installed. -

24-35 Top 50 0705

MAY contents volume 56/number 9 COVERSTORY With digital technologies occupying increasing space in our minds and lives, it’s no surprise that many of this year’s award winners took honors for innovations in the areas of marketing and merchandising, or that a number aligned themselves with another big trend that is making waves as technology makes more things possible: mass one-to-one customization. We say kudos to all of Apparel’s innovators, who continue to move the industry forward in interesting and unexpected ways. BY JORDAN K. SPEER, JESSICA BINNS AND DEENA M. AMATO-MCCOY Cover photography courtesy of Kokatat, Photo credit Jordy Searle INNOVATOR . .PAGE INNOVATOR . .PAGE Acustom Apparel . .17 Kokatat . .42 Aerosoles . .10 Koos Manufacturing . .21 Ascena Retail Group . .38 L. L. Bean . .22 Betabrand . .18 Lands' End Business Outfitters . .12 Brooks Brothers . .24 Macy's . .26 Buffalo Exchange . .34 Mitchells . .33 bumbrella . .37 Mizuno Running . .19 Canada Goose . .36 Mountain Equipment Co-op . .29 Chico's . .13 Performance Scrubs . .32 Dragon Crowd . .9 Rebecca Minkoff . .9 Everything But Water . .26 RG Barry . .41 Francesca's . .41 Stantt . .36 Garmatex . .17 SustainU . .33 Harry Rosen . .23 Timberland . .14 Hatley . .43 Topson Downs . .44 in the pink . .11 Twice as Nice Uniforms . .28 JustFab . .30 Under Armour . .21 Kathmandu . .20 Vestagen Technical Textiles . .15 TOP INNOVATOR SPONSORS BY JORDAN K. SPEER, JESSICA BINNS AND DEENA M. AMATO-MCCOY With digital technologies occupying increasing space in our minds and lives, it’s no surprise that many of this year’s award winners took honors for innovations in the areas of marketing and merchandising, or that a number aligned themselves with another big trend that is making waves as technology makes more things possible: mass one-to-one customization. -

The Peer Review Process-The Good Bad and Ugly

The Hospital Medical Staff Peer Review Process: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly Presented by: www.TheHealthLawFirm.com © Copyright 2017. George F. Indest III. All rights reserved. SUBTITLE: “Practical Matters the Physician Must Know When Confronted by a Medical Staff Peer Review/ Clinical Privileges/Fair Hearing Proceeding” Originally presented by George F. Indest III at an annual meeting of the American College of Surgeons Presented by: www.TheHealthLawFirm.com © Copyright 2017. George F. Indest III. All rights reserved. George F. Indest III, J.D., M.P.A., LL.M. Board Certified by the Florida Bar in the Legal Specialty of Health Law Website: www.TheHealthLawFirm.com Main Office: 1101 Douglas Avenue Altamonte Springs, Florida 32714 Phone: (407) 331-6620 Fax: (407) 331-3030 Website: www.TheHealthLawFirm.com “In the next fifteen minutes we have to create enough confusion to get out of here alive.” -Smith [Clint Eastwood] in “Where Eagles Dare” “If you want to play the game, you’d better know the rules….” -Inspector Harry Callahan [Clint Eastwood] in “The Dead Pool” TERMINOLOGY “Peer Review Hearing” a/k/a – Privileges Hearing – Fair Hearing – Medical Review Hearing – Credentials Hearing – Medical Staff Hearing – Disciplinary Hearing – Credentials Committee Hearing – Ad Hoc Committee Hearing The “Private Practice Physician” We are Discussing 1. Not a Hospital employee. 2. Does not have a direct contract with the Hospital. 3. Not a member of a group with an exclusive contract. 4. Does have clinical privileges at the Hospital. Two components of a physician’s medical staff relationship in a Hospital (often used interchangeably & incorrectly): 1. -

Film Locations in San Francisco

Film Locations in San Francisco Title Release Year Locations A Jitney Elopement 1915 20th and Folsom Streets A Jitney Elopement 1915 Golden Gate Park Greed 1924 Cliff House (1090 Point Lobos Avenue) Greed 1924 Bush and Sutter Streets Greed 1924 Hayes Street at Laguna The Jazz Singer 1927 Coffee Dan's (O'Farrell Street at Powell) Barbary Coast 1935 After the Thin Man 1936 Coit Tower San Francisco 1936 The Barbary Coast San Francisco 1936 City Hall Page 1 of 588 10/02/2021 Film Locations in San Francisco Fun Facts Production Company The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company During San Francisco's Gold Rush era, the The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company Park was part of an area designated as the "Great Sand Waste". In 1887, the Cliff House was severely Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) damaged when the schooner Parallel, abandoned and loaded with dynamite, ran aground on the rocks below. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Warner Bros. Pictures The Samuel Goldwyn Company The Tower was funded by a gift bequeathed Metro-Goldwyn Mayer by Lillie Hitchcock Coit, a socialite who reportedly liked to chase fires. Though the tower resembles a firehose nozzle, it was not designed this way. The Barbary Coast was a red-light district Metro-Goldwyn Mayer that was largely destroyed in the 1906 earthquake. Though some of the establishments were rebuilt after the earthquake, an anti-vice campaign put the establishments out of business. The dome of SF's City Hall is almost a foot Metro-Goldwyn Mayer Page 2 of 588 10/02/2021 Film Locations in San Francisco Distributor Director Writer General Film Company Charles Chaplin Charles Chaplin General Film Company Charles Chaplin Charles Chaplin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Warner Bros. -

Clint Eastwood

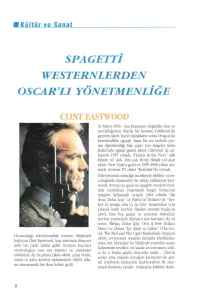

Kültür ue Sanat SPAGETT› WESTERNLERDEN OSCAR'LI YÖNETMENL›–E CLINT EASTWOOD 31 Mayıs 1930 / San Francisco doumlu olan ve çocukluunun büyük bir kısmını California'da geçiren aktör, liseyi bitirdikten sonra Oragon'da kerestecilikle ura˛tı, hatta bir ara orduda yüz- me öretmenlii bile yaptı. Los Angeles fiehir Kolejinde eitim gören aktör, Universal ile an- la˛arak 1955 yılında "Francis in the Navy" adlı filmde rol aldı. Pek çok B-tipi filmde rol alan aktör, New York'a geçti ve 1959-1966 yılları ara- sında western TV dizisi "Rawhide"da oynadı. Televizyonda edindii tecrübeyle birlikte oyun- culuunda minimalist bir üslup yakalayan East- wood, Avrupa'ya geçti ve spagetti western türü- nün unutulmaz yönetmeni Sergio Leone'nin spagetti üçlüsünde oynadı. 1964 yılında "Bir Avuç Dolar ›çin" (A Fistful of Dollars) ile "her- kes ya zengin olur ya da ölür" temasından yola çıkarak kanlı kovboy filmleri serisine ba˛layan aktör, ba˛ı bo˛ gezen ve acımasız Amerikalı kovboy portresiyle dünyaca üne kavu˛tu. ›ki yıl sonra "Birkaç Dolar ›çin" (For A Few Dollars More) ve efsane "›yi, Kötü ve Çirkin" (The Go- od, The Bad and The Ugly) filmlerinde oynayan Oyunculua televizyondaki western filmleriyle aktör, revizyonist western türünün klasiklerine ba˛layan Clint Eastwood, kısa zamanda dünyaca imza attı. Seyirciler bu filmlerde yaratılan sessiz ünlü bir yıldız haline geldi. Kariyeri boyunca kahramanı sevdiler, ne kadar az konu˛ursa etki- oyunculuun yanı sıra yapımcı ve yönetmen si de o kadar güçlü oluyordu sanki... Clint'in yönleriyle de ön plana çıkan aktör, uzun boylu, sessiz ama anlamlı duru˛ları Leone'nin de gör- sessiz ve kaba kovboy tiplemesiyle 1960'lı yılla- sel üslubuyla birle˛erek Eastwood'un ilk sine- rın sinemasında bir ikon haline geldi. -

WMS Industries Inc. ”

we LISTEN 2 0 0 9 ANNUAL REPORT W M S I N D U S TR I E S I NC. WMS “SUCCeeDS and continues to achieve profitable GROWTH because we carefully LISTEN to our EMPLOYees & CUSTOmeRS. WMS Industries Inc. ” LIS·TEN (verb) 1. TO PAY ATTENTION 2. TO HEAR WITH THOUGHTFUL CONSIDERATION: TO HEED 3. TO BE ALERT TO CATCH AN EXPECTED SOUND WMS is known worldwide for our groundbreaking gaming experiences and cutting-edge industry technology. Behind our progress and advancement lies a strong Culture of Innovation: an organizational community in which every voice is heard. We have built a formidable talent base and a culture of open minds that remain alert to marketplace changes; and we have the courage to heed what we hear and execute with imagination and insight. 1 WL E ISTEN… a thought, a sound, AN IDEA, an image, a story, an evolution of sustainable long-term growth. STORIE S of a Successful IDEA Mark Foster Damon Gura Human Resources, Director, Advanced R&D, Director, Organizational Development Advanced Applications “ There is a genuine sense of “ Our culture feeds on itself. community, teamwork and Ideas are not only encouraged engagement of our people to and appreciated; they drive accomplish more than we our passion.” can independently.” Colleen Stanton Arturo Hernandez Marketing, Senior Marketing Manager Norm Wurz Manufacturing, Production Supervisor Engineering and Technology, Vice President, Hardware Development “ Great products are no accident—they “ Everyone is valued for their contri- result from a systematic approach and “ We deliver innovative, -

Dirty Harry and the Real Constitution Michael Stokes Paulsent

REVIEW Dirty Harry and the Real Constitution Michael Stokes Paulsent The Constitution and CriminalProcedure: First Principles. Akhil Reed Amar. Yale University Press, 1997. Pp xi, 272. I. PROLOGUE: DIRTY HARRY, 1977 I didn't see Dirty Harry until my freshman year in college, in 1977, at a $1 Midnight Madness showing at the university center. But it was a memorable event: a rowdy, college audience cheering as one for the quintessential 1970s anti-hero hero, hard-bitten Inspector Harry Callaghan of the San Francisco Police Depart- ment, played by the squinting Clint Eastwood, as he did battle with a truly evil serial killer/child-kidnapper-and with the up- side-down, criminal-coddling legal system that freed this monster to kill and terrorize more victims. It would be dramatizing to say that this flick led me to law school (and to my brief stint as a federal prosecutor), but one scene does remain blazed in my memory twenty years later. In- spector Callaghan-"Dirty Harry'--has agreed to carry the ran- t Associate Professor of Law, University of Minnesota Law School. The reader should be aware that Akhil Amar and I were accidental law school roommates at Yale in 1982-83 and argued frequently and vehemently about some of the very same issues discussed here. Our disagreements remained friendly, however, and Professor Amar and I remain friends today (despite our disagreements). Friendship does not keep me from taking potshots at him in print, when he deserves them (as he does, to some extent, here). See, for example, Michael Stokes Paulsen, Double Jeopardy Law After Akhil Amar: Some Civil Procedure Analogies and Inquiries,26 Cumb L Rev 23, 23 n 1 (1995). -

Social Ills and the One-Man Solution: Depictions of Evil in the Vigilante Film

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 301 896 CS 506 482 AUTHOR Novak, Glenn D. TITLE Social Ills and the One-Man Solution: Depictions of Evil in the Vigilante Film. PUB DATE Nov 87 NOTE 20p.; Paper presented at the International Conference on the Expressions of Evil in Literature and the Visual Arts (Atlanta, GA, November 6-8, 1987). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Speeches /Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Citizen Role; Content Analysis; *Film Study; Media Research; Popular Culture; Social Problems; Urban Culture; *Urban Problems; Victims of Crime IDENTIFIERS *Evil; Film Genres; *Vigilante Films ABSTRACT Depictions of evil in the modern American vigilante film of the 1970s and 1980s fall into several categories. Modern vigilante film may be defined as film concerning the efforts of a private citizen in the late twentieth century urban environments of New York City or Los Angeles to operate outside the law in ridding the streets of evil and crime. Examples of such films include the "Death Wish" trilogy, and "Sudden Impact." Categories of depictions of evil include: (1) expressions of evil in society (the breakdown of social order, wicked youth, corrupt justice systems); (2) expressions of evil in the appearance of the criminal and in the behavior of the criminal; and (3) the protagonist as evil (discussing the moral and physical journey from respectable, normal citizen through physical danger and moral ambiguity to excessive, contemptible violence, i.e. the transformation from goodness through amorality to evil). The social implications of evil in the vigilante film include increased fear of victimization as a result of watching violence on television and in films, and the blurring of the distinction between good and evil.