1-Abdul Haseeb Ansari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and Country Reports

Flash Report 01/2017 Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and country reports EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Unit B.2 – Working Conditions Flash Report 01/2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 ISBN ABC 12345678 DOI 987654321 © European Union, 2017 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Flash Report 01/2017 Country Labour Law Experts Austria Martin Risak Daniela Kroemer Belgium Wilfried Rauws Bulgaria Krassimira Sredkova Croatia Ivana Grgurev Cyprus Nicos Trimikliniotis Czech Republic Nataša Randlová Denmark Natalie Videbaek Munkholm Estonia Gaabriel Tavits Finland Matleena Engblom France Francis Kessler Germany Bernd Waas Greece Costas Papadimitriou Hungary Gyorgy Kiss Ireland Anthony Kerr Italy Edoardo Ales Latvia Kristine Dupate Lithuania Tomas Davulis Luxemburg Jean-Luc Putz Malta Lorna Mifsud Cachia Netherlands Barend Barentsen Poland Leszek Mitrus Portugal José João Abrantes Rita Canas da Silva Romania Raluca Dimitriu Slovakia Robert Schronk Slovenia Polonca Končar Spain Joaquín García-Murcia Iván Antonio Rodríguez Cardo Sweden Andreas Inghammar United Kingdom Catherine Barnard Iceland Inga Björg Hjaltadóttir Liechtenstein Wolfgang Portmann Norway Helga Aune Lill Egeland Flash Report 01/2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................. -

Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense

63 Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense Article 15: Criminal Offense A criminal offense is an unlawful act: (a) that is prescribed as a criminal offense by law; (b) whose characteristics are specified by law; and (c) for which a penalty is prescribed by law. Commentary This provision reiterates some of the aspects of the principle of legality and others relating to the purposes and limits of criminal legislation. Reference should be made to Article 2 (“Purpose and Limits of Criminal Legislation”) and Article 3 (“Principle of Legality”) and their accompanying commentaries. Article 16: Criminal Responsibility A person who commits a criminal offense is criminally responsible if: (a) he or she commits a criminal offense, as defined under Article 15, with intention, recklessness, or negligence as defined in Article 18; IOP573A_ModelCodes_Part1.indd 63 6/25/07 10:13:18 AM 64 • General Part, Section (b) no lawful justification exists under Articles 20–22 of the MCC for the commission of the criminal offense; (c) there are no grounds excluding criminal responsibility for the commission of the criminal offense under Articles 2–26 of the MCC; and (d) there are no other statutorily defined grounds excluding criminal responsibility. Commentary When a person is found criminally responsible for the commission of a criminal offense, he or she can be convicted of this offense, and a penalty or penalties may be imposed upon him or her as provided for in the MCC. Article 16 lays down the elements required for a finding of criminal responsibility against a person. -

Stirling Silliphant Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2f59n87r No online items Finding Aid for the Stirling Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Finding aid prepared by Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 14 August 2017 Finding Aid for the Stirling PASC.0134 1 Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Title: Stirling Silliphant papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0134 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 27.0 linear feet65 boxes. Date (inclusive): ca. 1950-ca. 1985 Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Stirling Silliphant Papers (Collection Number PASC 134). -

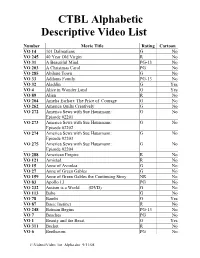

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

'Jaws'. In: Hunter, IQ and Melia, Matthew, (Eds.) the 'Jaws' Book : New Perspectives on the Classic Summer Blockbuster

This is the accepted manuscript version of Melia, Matthew [Author] (2020) Relocating the western in 'Jaws'. In: Hunter, IQ and Melia, Matthew, (eds.) The 'Jaws' book : new perspectives on the classic summer blockbuster. London, U.K. For more details see: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/the-jaws-book-9781501347528/ 12 Relocating the Western in Jaws Matthew Melia Introduction During the Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium1 Carl Gottlieb, the film’s screenwriter, refuted the suggestion that Jaws was a ‘Revisionist’ or ‘Post’ Western, and claimed that the influence of the Western genre had not entered the screenwriting or production processes. Yet the Western is such a ubiquitous presence in American visual culture that its narratives, tropes, style and forms can be broadly transposed across a variety of non-Western genre films, including Jaws. Star Wars (1977), for instance, a film with which Jaws shares a similar intermedial cultural position between the Hollywood Renaissance and the New Blockbuster, was a ‘Western movie set in Outer Space’.2 Matthew Carter has noted the ubiquitous presence of the frontier mythos in US popular culture and how contemporary ‘film scholars have recently taken account of the “migration” of the themes of frontier mythology from the Western into numerous other Hollywood genres’.3 This chapter will not claim that Jaws is a Western, but that the Western is a distinct yet largely unrecognised part of its extensive cross-generic hybridity. Gottlieb has admitted the influence of the ‘Sensorama’ pictures of proto-exploitation auteur William Castle (the shocking appearance of Ben Gardner’s head is testament to this) as well as The Thing from Another World (1951),4 while Spielberg suggested that they were simply trying to make a Roger Corman picture.5 Critical writing on Jaws has tended to exclude the Western from the film’s generic DNA. -

PDF of the Résumé Below

SCOTT TRIMBLE Extremophiles Inc., 22287 Mulholland Highway #231, Calabasas, CA 91302, USA cell 310‐528‐1241, email [email protected], website www.ststlocations.com Hollywood Teamsters Local 399 ||| Location Managers Guild International (Board of Directors) California On Location Awards: 5 Wins and 14 Nominations ||| LMGI Awards: 1 Nomination ||| COVID‐19 Fully Vaccinated Comic‐Con Panel Moderator ||| Past travel includes all fifty U.S. States ||| Eagle Scout ||| U.C. Berkeley Grad in Archæology PRODUCER / PRODUCTION MANAGER Ghostbusters: Afterlife (Dan Aykroyd) feature / Sony Pictures Entertainment • PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR (L.A. UNIT) — Southern California Star Wars: The Book of Boba Fett (Tem Morrison) season 1 / Disney / Lucasfilm Ltd. • PROD. SUPERVISOR (VFX Units) / KEY LOC. MGR. — ##### / ##### / SoCal Star Wars: The Mandalorian (Pedro Pascal) episode 2.08 / Disney / Lucasfilm Ltd. • PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR (VFX Unit) — Death Valley (Post-Credits Epilogue) She’s in Portland (Tommy Dewey & François Arnaud) feature / Son of the Knife Films • CO-PRODUCER / SUPERVISING LOC. MANAGER — Oregon / NorCal / SoCal Fast & Furious: Supercharged (Orlando Ride) theme park / Universal / Extremophiles • CO-PRODUCER / UNIT PROD. MGR. (VFX Unit) — Northern California Jurassic World (Chris Pratt) feature / 32Ten Studios / Universal • PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR (VFX Unit) — Northern California Star Trek: Prelude to Axanar (Kate Vernon) short film / Axanar Productions • UNIT PRODUCTION MANAGER — Southern California Fast & Furious: Supercharged (Universal -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat. -

Research and Analysis Essay

Research and Analysis Essay OBJECTIVES The purpose of this essay is for you to: a) broaden your knowledge of 1970s American cinema and society and b) hone skills of writing and critical analysis. GUIDELINES You will choose one of the general topics provided below and carve out of it your own specific analysis. Try to be specific and focused. Construct a thesis in your introduction that outlines what you will argue and focus on; then, continually reinforce, point back to, and illustrate this thesis in the body; and wrap up your paper and thesis in the conclusion. Regardless of which topic you choose, this essay requires you to combine the following: A) research, whereby you will locate and cite scholarly writings that strengthen your study; and B) analysis, in which you will make sense of and think critically about the subject matter. Be sure, as well – again, regardless of topic – to examine in some way the relationship between American cinema and society in the 1970s. TOPICS Choose one of these below. Be careful not to tackle the entire topic, which would not be advisable in such a short paper. Instead find a topic below that interests you and go about finding a particular area within it that will permit you to accomplish the objectives and follow the guidelines. 1. New genres — Pick one of the new genres that came out of the 1970s. Consider why this genre and movie (could be as many as two movies) emerge during the 1970s. How does it generically address issues particularly relevant to 1970s America? And, in turn, how does the film generically determine its aesthetics, themes, and/or ideology? How is the film representative of that genre and of the decade? The films below are mere suggestions; you may find others. -

The Interaction Between Politics and Popular Culture at the End of Wars

Conflict, Culture, Closure: The interaction between politics and popular culture at the end of wars Cahir O’Doherty A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University August 2019 ii Abstract In this thesis I engage with the topic of how popular culture and politics interact at the end of conflict. Using contemporary Hollywood action cinema from 2000 to 2014 and political speeches from the Bush and Obama administrations, I pose the question of how do these seemingly disparate fields forge intense connections between and through each other in order to create conditions of success in the War on Terror. I utilise the end of wars assemblage to argue that through intense and affective encounters between cinema screen and audiences, certain conditions of success emerge from the assemblage. These conditions include American exceptionalism and the values it exemplifies; the use of technology in warfare as co-productive of moral subjectivities; the necessity of sacrifice; and the centrality of the urban landscape and built environment. I then proceed to assess the resilience of the end of wars assemblage and its conditions of success by engaging with cinematic and political artefacts that have the potential to destabilise the assemblage through genre inversion and alternative temporalities. Ultimately, I argue that the assemblage and its conditions of success are strongly resilient to change and critique. The conditions of success that emerge from the assemblage through intense affective encounters can then be politically deployed make a claim that a war has ended or will end. Because audiences have been pre-primed to connect these conditions to victory, such a claim has greater persuasive power.