Showgirls Comes of Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

Winter 2020-21 Edition Contents

Artwork By: Stefanii Adler Winter 2020-21 Edition www.fcaq.k12.ec Contents + Academics / Académico + Health & Entertainment / Salud & Entretenimiento 6 Students Motivation 36 Feel Good List of Season Movies (New Year's, Christmas) 2019 10 Online Classes 38 Blue Light Impact on Eye Sight 12 Quarantine Effect on Grades 40 The Impact Of The Pandemic On Teenagers' Mental Health 42 You Are What You Pollute + Arts & Culture / Arte & Cultura + Special Features / Extras 24 New Clubs!! 46 The Meaning of Christmas 26 Trends you didn't know were Black Born 3 48 Sign Language 28 Why Studying Art is Beneficial 50 The Origin of Christmas Traditions 31 Ballroom Culture 52 Distorting "The Beautiful Game" 31 CAMINU Why Winter Is A Season To Look Forward To 54 and the Upcoming Year 56 How Christmas Is Celebrated Around The World Mauris ligula sollicitudin. Maecenas netus, vivamus mollis dui. vivamus Mauris ligula sollicitudin. Maecenas netus, Winter 2020 | School Views fcaq.k12.ec 3 2018 Academics 2019 Académico 4 Students Motivation Victoria G. 5 Isabella A. Online Classes BÁrbara B. Luciana S. Quarantine Picture by: Veronica Missura Effect On Grades Emilia S. www.alexkoin.com mollis dui. vivamus Mauris ligula sollicitudin. Maecenas netus, Winter 2020-21 | School Views fcaq.k12.ec 5 There are several ways to do this: Victoria Gangotena and Isabella Aliyev Just take a moment for yourself and get the chance to truly feel grateful for everything that surrounds you. Motivational Letter to Students and Teachers Take risks and change your daily routine by doing things that you’ve never done before; for ex- ample, yoga, meditation, drawing, playing an instrument, etc. -

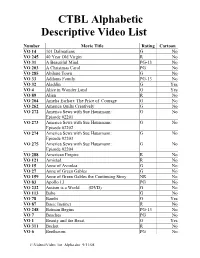

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

![1 [27] Ficvaldivia 2 [27] Ficvaldivia 3 [27] Ficvaldivia 4 [27] Ficvaldivia 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7781/1-27-ficvaldivia-2-27-ficvaldivia-3-27-ficvaldivia-4-27-ficvaldivia-5-317781.webp)

1 [27] Ficvaldivia 2 [27] Ficvaldivia 3 [27] Ficvaldivia 4 [27] Ficvaldivia 5

[27] FICVALDIVIA 1 [27] FICVALDIVIA 2 [27] FICVALDIVIA 3 [27] FICVALDIVIA 4 [27] FICVALDIVIA 5 [27] FICVALDIVIA Palabras6 9 Words FILMES DE INAUGURACIÓN Filmes de inauguración 26 Opening films Y CLAUSURA OPENING AND CLOSING Filmes de clausura 28 FEATURES P. 25 Closing films Cortometraje de Ceremonia de Premiación 30 Awards Ceremony Short Film JURADO Y ASESORES 33 JURY AND ADVISORS P.33 EN COMPETENCIA Selección Oficial Largometraje Internacional 45 IN COMPETITION Official International Feature Selection P. 44 Selección Oficial Largometraje Chileno 59 Official Chilean Feature Selection Selección Oficial Largometraje Juvenil 67 Internacional Official International Youth Feature Selection Selección Oficial Cortometraje 75 Latinoamericano Official Latin-American Short Film Selection Selección Oficial Cortometraje Infantil 89 Latinoamericano Official Latin-American Children’s Short Film Selection Selección Oficial Cine Chileno del Futuro 96 Future Chilean Cinema Official Selection [27] FICVALDIVIA 7 MUESTRA PARALELA CINEASTAS EN FOCO 105 Video y Estallido Social 178 PARALLEL PROGRAM FILMMAKERS IN THE Video and Social Uprising P. 105 SPOTLIGHT MUESTRA CINE 185 Ana Poliak 106 RETROSPECTIVA RETROSPECTIVE PROGRAM Colectivo Los Hijos 112 Clásicos 186 Latinas a la vanguardia 122 Classics Guillaume Brac 131 VHS Erótico 190 Erotic VHS MUESTRA CINE 139 CONTEMPORÁNEO Vazofi: Bazofi en Valdivia 193 CONTEMPORARY CINEMA Vazofi: Bazofi in Valdivia PROGRAM Gala 140 PÁSATE UNA PELÍCULA 201 Gala WHAT’S YOUR STORY! HOMENAJES 146 Largometrajes familiares 202 TRIBUTES -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Presto in January

Media Release: Thursday, December 17, 2015 Presto in January True Detective season 1 starts its investigation on Presto along with new seasons of Ray Donovan, Penny Dreadful and The Americans Presto today announced key programming set to kick off the New Year starting with the critically acclaimed True Detective (season 1). The edge-of-your-seat anthology crime drama is a Presto SVOD exclusive and centres on the lives of Louisiana State Police homicide detectives Rustin "Rust" Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) and Martin "Marty" Hart (Woody Harrelson) and follows a seventeen- year journey of flashbacks where the two detectives recount a murder. With the perpetrator still at large, it’s a race against time for these two men to piece things together and stop the cycle. Also streaming in January, is the third season of tough guy drama, Ray Donovan starring Liev Schreiber, as the title character. Ray is a "fixer" for L.A.’s elite celebrities, athletes and business moguls when they need to make their problems disappear. But no amount of money can mask Ray's past, which continues to haunt him and threatens to destroy everything he has built for himself. Many people are familiar with the classic tales of Dr. Frankenstein and Dorian Gray. Penny Dreadful brings those and other characters into a new light by exploring their origin stories in this psychological thriller that takes place in the dark corners of Victorian London. Presto adds season 2 from January. Finally, The Americans introduces viewers to Philip and Elizabeth Jennings, two KGB spies in an arranged marriage who are posing as Americans during the 1980s. -

Telling Lies in America Joe Eszterhas Is a Big-Bucks Screenwriter Who

Telling Lies in America Joe Eszterhas is a big-bucks screenwriter who earned millions for slick trash (like Flashdance and Basic Instinct) and total trash (Jade, Showgirls) but who now has returned to his roots with his latest script. Very different from his previous efforts is Telling Lies to America , a coming of age story about a Hungarian immigrant kid growing up poor and ambitious in Cleveland (Eszterhas’ hometown), in the early 1960’s era of burgeoning rock n’ roll. The kid is teenager Karchy Jonas (Brad Renfro), an outsider at his high school who still has trouble pronouncing that tough “th” of English and who has to work nights at an egg plant to help support his factory worker father (Maximilian Schell). Karchy has an inchoate desire for a better life and grabs his chance when a local celebrity, slick disc jockey Billy Magic (Kevin Bacon) takes him on as a go-fer. Billy, willing to plug teenybopper tunes for dough, really loves rhythm and blues (what he calls “sweaty collars and dirty fingernails music”), and he humors Karchy because he recognizes his own deceitful youth in the lad. In a new cool jacket, Karchy dreams of being a dj himself, complete with the girls, the hot car, and the flash he sees Billy possesses. His newfound hustle, however, loses him the respect of his old-country father and his co-worker and girlfriend Diney (Calista Flockhart), and, when he gets mired in Billy’s payola schemes as a material witness for government investigators, he learns the price of prevaricating to get ahead. -

Children of Glory

ANDREW G. VAJNA PRESENTS CHILDREN OF GLORY Cast: Iván Feny ı Kata Dobó Sándor Csányi Károly Gesztesi Original Story by: Joe Eszterhas Writing Credits by : Joe Eszterhas Eva Gárdos Géza Bereményi Réka Divinyi Co-Producers : Clive Parsons S. Tamás Zákonyi Cinematography by : Buda Gulyás Production Desing by : János Szabolcs Costume Desing by : Beatrix Aruna Pásztor Original Music by : Nick Glennie-Smith Producer: Andrew G. Vajna Directed by : Krisztina Goda Website: www.szabadsagszerelemafilm.hu SYNOPSIS The year is 1956. While Hungary is only a small slave nation within the massive Soviet Block, it is also a superpower – its national water polo team is invincible. Even locked behind the Iron Curtain, the players feel like kings. Thriving on success and enjoying the attention of every girl in the country, they stand self-assured and unified. The team has lost only once in 1955, when a referee in Moscow simply did not let them win. The team are now bracing themselves for a rematch due to take place at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne. History, however, throws a major obstacle in team’s path, and a revolution breaks out in Budapest and the young star of the team, Karcsi (Iván Feny ı) and his friend, Tibi (Sándor Csányi) get embroiled in the events occurring out on the streets. At first, they are only out for adventure, but a fiery student - Viki Falk (Kata Dobó) - from the Technical University catches Karcsi’s eye and in following her steps he finds himself right at the heart of the uprising - the Kossuth square and the subsequent siege of the National Radio station. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires Cesare Marchetti and Jesse H. Ausubel FOREWORD Humans are territorial animals, and most wars are squabbles over territory. become global. And, incidentally, once a month they have their top managers A basic territorial instinct is imprinted in the limbic brain—or our “snake meet somewhere to refresh the hierarchy, although the formal motives are brain” as it is sometimes dubbed. This basic instinct is central to our daily life. to coordinate business and exchange experiences. The political machinery is Only external constraints can limit the greedy desire to bring more territory more viscous, and we may have to wait a couple more generations to see a under control. With the encouragement of Andrew Marshall, we thought it global empire. might be instructive to dig into the mechanisms of territoriality and their role The fact that the growth of an empire follows a single logistic equation in human history and the future. for hundreds of years suggests that the whole process is under the control In this report, we analyze twenty extreme examples of territoriality, of automatic mechanisms, much more than the whims of Genghis Khan namely empires. The empires grow logistically with time constants of tens to or Napoleon. The intuitions of Menenius Agrippa in ancient Rome and of hundreds of years, following a single equation. We discovered that the size of Thomas Hobbes in his Leviathan may, after all, be scientifically true. empires corresponds to a couple of weeks of travel from the capital to the rim We are grateful to Prof. Brunetto Chiarelli for encouraging publication using the fastest transportation system available.