Film Essay for "Dirty Harry"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noviembre 2010

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 913691125 (taquilla) Fax: 91 4672611 913692118 [email protected] (gerencia) http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html Fax: 91 3691250 NIPO (publicación electrónica) :554-10-002-X MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala noviembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2010 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 16.15 - 00.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.00 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico NOVIEMBRE 2010 Don Siegel (y II) III Muestra de cine coreano (y II) VIII Mostra portuguesa Cine y deporte (III) I Ciclo de cine y archivos Muestra de cine palestino de Madrid Premios Goya (II) Buzón de sugerencias: Hayao Miyazaki Cine para todos Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. -

Cultural Commentary: Affectional Preference on Film: Giggle and Lib Joseph J

Bridgewater Review Volume 1 | Issue 2 Article 9 Dec-1982 Cultural Commentary: Affectional Preference on Film: Giggle and Lib Joseph J. Liggera Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation Liggera, Joseph J. (1982). Cultural Commentary: Affectional Preference on Film: Giggle and Lib. Bridgewater Review, 1(2), 21-22. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol1/iss2/9 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. CULTURAL COMMENTARY Affectional Preference on Film: Giggle and Lib omantic attachments on screen the romantic man whose passionate desire With the great artist abandoning R these days require at least a hint of is for a person unquestionably of the romantic love--Bergman has lately something kinky to draw the pop audience opposite sex. So straight are his lusts that announced that his next two films will be his which in the days of yesteryear thrilled to no one seemed to notice the dilemma posed last--leaving the field to an oddity like Allen Bogart and Bacall, but which now winks in Manhattan of a man in his mid-forties or television's "Love Boat", the pop knowingly at Julie Andrews in drag. having physical congress with a fifteen year audience, which never warmed to Bergman Something equally aberrant, in fact moreso, old. This year, A -Midsummer Night's Sex or his like anyway, might find solace in Blake more blatant and proselytizing, quickens Comedy renders two points of sexual Edwards, an intriguing director whose last the mental loins of the liberal film-going metaphysics for those still lost in memories three films and his wife's, Julie Andrews, mind; anything less denies the backbone of a gender-differentiated past, the first changing image in them illustrate a syn upon which liberal sentiments are oddly enough insisted upon by the women: if thesis of audience demands with a structured. -

Stirling Silliphant Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2f59n87r No online items Finding Aid for the Stirling Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Finding aid prepared by Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 14 August 2017 Finding Aid for the Stirling PASC.0134 1 Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Title: Stirling Silliphant papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0134 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 27.0 linear feet65 boxes. Date (inclusive): ca. 1950-ca. 1985 Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Stirling Silliphant Papers (Collection Number PASC 134). -

Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm

JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 3 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm Edited by Cristina M. Giannantonio Amy E. Hurley-Hanson Associate Professors of Management, George L. Argyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, USA NEW HORIZONS IN LEADERSHIP STUDIES Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 4 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 © Cristina M. Giannantonio andAmy E. Hurley-Hanson 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946802 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Business Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78100 212 4 ISBN 978 1 78100 211 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:57:46 2013 14. Extreme leadership as creative leadership: reflections on Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Charalampos Mainemelis and Olga Epitropaki INTRODUCTION How do extreme leadership situations arise? According to one view, they are triggered by environmental factors that have nothing or little to do with the leader. -

Die Invasion Der Barbaren Gedanken Zur Re-Mythisierung Hollywoods in Den 1980Er-Jahren

Die Invasion der Barbaren Gedanken zur Re-Mythisierung Hollywoods in den 1980er-Jahren Marcus Stiglegger, Berlin 1. Wenn ich zurückdenke an das Jahr 1982 – ich war gerade 11 Jahre alt –, muss ich sagen, dass Conan für kurze Zeit zu meinem Mentor wurde. Ich durfte den Film mit Arnold Schwar- zenegger damals noch nicht sehen und sammelte daher verzweifelt alle Artikel über John Milius’ CONAN THE BARBARIAN (1982), die ich finden konnte. So kaufte ich mein erstes Cinema-Heft und meine erste Bravo-Ausgabe, denn beide berichteten ausführlich über den archaischen Barbaren. Und welche Freude war es, als der Heyne Verlag mit seiner Veröf- fentlichung der Conan-Stories und -Romane begann, die jeweils mit einem Filmfoto auf dem Cover erschienen. Diese blassgelben Buchrücken schmücken noch heute mein Lesezimmer. Conan kam damals zur richtigen Zeit: mit der wachsenden Popularität von J. R. R. Tolkiens Herr der Ringe-Romantrilogie und dem gleichnamigen Animationsfilm von Ralph Bakshi aus dem Jahr 1979, mit John Boormans 1981 gestarteter Neuinterpretation des Arthus-Mythos’ in EXCALIBUR und Terry Gilliams TIME BANDITS (1981). Es folgten THE DRAGON SLAYER (1982) von Matthew Robbins, FIRE AND ICE (1983) von Ralph Bakshi, THE DARK CRYSTAL (1982) von Jim Hanson und Frank Oz, LEGEND (1983) von Ridley Scott und aus Deutsch- land DIE UNENDLICHE GESCHICHTE (1984) von Wolfgang Petersen. Und nicht nur das Kino feierte die Phantasie, auch das Table-Top-Rollenspiel Dungeons & Dragons hatte damals eine Hochphase. Tolkiens Mittelerde hatte sich bereits in der Hippie-Ära der frühen 1970er-Jahre großer Beliebtheit erfreut, Studierendenkreise ebenso inspiriert wie esoterische Beschäfti- gung angestoßen. Pen-and-Paper-Rollenspiele etablierten sich als Gruppenerlebnis, und schon in den 1970er-Jahren musste man von einem Revival jener Fantasy-Literatur sprechen, die eigentlich einer anderen Ära entstammte: den krisengeplagten 1930er-Jahren mit ihren ‚Weird Tales‘ und weiteren frühen Fantasy-Magazinen. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 Entertainment for the Whole Family! You have to wonder if Michael McCambridge ever got to watch a hockey game before he ended up with somebody’s, well, you know. His mother, Charlestown Chiefs owner Anita McCambridge, wasn’t above violence in hockey as long as she could make a profi t from it, but she’d be damned if she would ever allow her children to watch the sport. Kids are impressionable, you see. They might stick up a bank. Heroin. You name it. ImagineCOPYRIGHTED Anita’s horror at learning MATERIALthat the members of her former hockey team, the scourge of the Federal League, over time had evolved but not necessarily changed; they’re still the face of goon hockey at its peak. But, strangely, they’ve also become the epitome of family-friendly entertainment. The Hanson Brothers were initially shunned and mocked by their disapproving teammates. Their intellect, or lack - 1 - EE1C01.indd1C01.indd 1 77/16/10/16/10 110:38:380:38:38 AAMM The Making of Slap Shot thereof, was called into question by their coach who found them so frightfully bizarre that he vowed they would not play for his club. Today, however, they are idolized by millions of fans around the world, from 82-year-old legend Gordie Howe to children whose parents weren’t even born when the Hansons stepped onto the War Memorial ice to com- mence what fans have dubbed “the greatest shift in hockey history.” Go ahead, Google it. You’ll see. It’s diffi cult to explain the transformation of the Hansons from “retards” and “criminals” to icons who still tour North American arenas every year, dispensing their special brand of tough, in-your-face hockey, without having changed a whole lot about their style. -

Isaac Asimov's Super Quiz

PAGE 6A WEDNESDAY, JULY 7, 2021 TIMES WEST VIRGINIAN ADVICE Dear Mayo Clinic Q and A: Simplify health Annie Annie Lane goals for success Syndicated Columnist that includes things such as: every other day with a meal. This can be By Cynthia Weiss – Ridding homes of any desserts, candy, something you can easily manage and Mayo Clinic News Network soda and processed food. feel successful with. Just remember not Dear Mayo Clinic: I am a mom of three – Promising to buy and eat only whole to overload it with dressing. Or instead of kids under 10, and I have struggled with foods made from scratch. grabbing a handful of chips for a snack, Twin brothers weight loss for years. I am challenged – Going to the gym five or more days a grab an apple or a cheese stick. Consider the between family and work obligations to week and working out for an hour each time. same substitutions for your children so you maintain a healthy lifestyle. I always start – Hiring a life coach to help get their life won’t be tempted. can’t get along off strong, but then I get overwhelmed and together. Over time, one change will lead to stop. Last month, despite trying to eat right – Reducing work stress. another. As you implement healthy things Dear Annie: I come from a big family. I and working out daily, I gained weight after Does this sound familiar? into your routine, you will build more have seven brothers and two sisters, and I’m two weeks instead of losing it. -

Clint Eastwood Et Les Années 1980 Julien Fonfrède

Document generated on 09/28/2021 9:57 a.m. 24 images Papy fait de la résistance Clint Eastwood et les années 1980 Julien Fonfrède Années 1980 – Laboratoire d’un cinéma populaire Number 183, August–September 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/85996ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Fonfrède, J. (2017). Papy fait de la résistance : Clint Eastwood et les années 1980. 24 images, (183), 31–31. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Années 1980 – Laboratoire d’un cinéma populaire PAPY FAIT DE LA RÉSISTANCE CLINT EASTWOOD ET LES ANNÉES 1980 par Julien Fonfrède es réalisateurs, acteurs et actrices phares D des décennies précédant les années 1980, nombreux sont ceux et celles qui sont tombés dans l’oubli au cours de cette période. Le cinéma rajeunit alors. Une nouvelle génération de réali- sateurs, de spectateurs, de sujets et de visages débarque. Difficile, pour beaucoup, de s’adapter aux changements. Pour Clint Eastwood, ce ne sera en revanche pas le cas. -

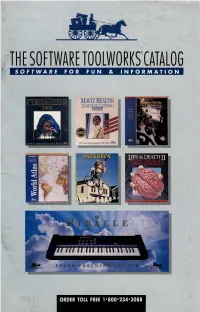

Thf SO~Twarf Toolworks®Catalog SOFTWARE for FUN & INFORMATION

THf SO~TWARf TOOlWORKS®CATAlOG SOFTWARE FOR FUN & INFORMATION ORDER TOLL FREE 1•800•234•3088 moni tors each lesson and builds a seri es of personalized exercises just fo r yo u. And by THE MIRACLE PAGE 2 borrowi ng the fun of vid eo ga mes, it Expand yo ur repertoire ! IT'S AMIRAClf ! makes kids (even grown-up kids) want to The JI!/ irac/e So11g PAGE 4 NINT!NDO THE MIRACLE PIANO TEACHING SYSTEM learn . It doesn't matter whether you 're 6 Coflectioll: Vo/11111e I ~ or 96 - The Mirttcle brings th e joy of music adds 40 popular ENT!RTA INMENT PAGE/ to everyo ne. ,.-~.--. titles to your The Miracle PiC1110 PRODUCTI VITY PAGE 10 Tet1dti11gSyste111, in cluding: "La Bamba," by Ri chi e Valens; INFORMATION PAGElJ "Sara," by Stevie Nicks; and "Thi s Masquerade," by Leon Russell. Volume II VA LU EP ACKS PAGE 16 adds 40 MORE titles, including: "Eleanor Rigby," by John Lennon and Paul McCartney; "Faith," by George M ichael; Learn at your own pace, and at "The Girl Is M in e," by Michael Jackson; your own level. THESE SYMBOLS INDICATE and "People Get Ready," by C urtis FORMAT AVAILABILITY: As a stand-alone instrument, The M irt1de Mayfield. Each song includes two levels of play - and learn - at yo ur own rivals the music industry's most sophis playin g difficulty and is full y arra nged pace, at your own level, NIN TEN DO ti cated MIDI consoles, with over 128 with complete accompaniments for a truly ENTERTAINMENT SYST!M whenever yo u want. -

Dirty Harry Quand L’Inspecteur S’En Mêle Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 Minutes Pascal Grenier

Document generated on 09/25/2021 3:09 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Dirty Harry Quand l’inspecteur s’en mêle Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 minutes Pascal Grenier Animer ailleurs Number 259, March–April 2009 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/44930ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Grenier, P. (2009). Review of [Dirty Harry : quand l’inspecteur s’en mêle / Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 minutes]. Séquences, (259), 32–32. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2009 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 3 ARRÊT SUR IMAGE I FLASH-BACK Dirty Harry I Quand l'inspecteur s'en mêle Un inspecteur aux méthodes expéditives lutte contre un psychopathe dangereux qui menace la population de San Francisco. Sorti en 1971, ce drame policier fort percutant créa toute une controverse à l'époque. Clint Eastwood est propulsé au rang de star et son personnage, plus grand que nature, est encore aujourd'hui une véritable icône cinématographique. PASCAL GRENIER irty Harry marque la quatrième collaboration entre le réalisateur Don Siegel et le comédien Clint Eastwood D après Coogan's Bluff, Two Mules for Sister Sara et The Beguiled. -

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’S Impact on the Western

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’s Impact on the Western Jacob A. Williams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Claudia Gorbman E. Joseph Sharkey Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Section I The Anti-Hero: Newborn or Reborn Hero? 4 Section II A Greek Tradition: Violence as Catharsis 11 Section III The Theseus Theory 21 Section IV A Modern Greek Tale: The Outlaw Josey Wales 31 Section V The Euripides Effect: Bringing the Audience on Stage 40 Section VI The Importance of the Western Myth 47 Section VII Conclusion: The Immortality of the Western 49 Bibliography 53 Sources Cited 62 i Dedication To my wife and children, whom I cherish every day: To Brandy, for always being the one person I can always count on, and for supporting me through this entire process. You are my love and my life. I couldn’t have done any of this without you. To Andrew, for always being so responsible, being an awesome big brother to your siblings, and always helping me whenever I need you. You are a good son, and I am proud of the man you are becoming. To Tristan, for always being my best friend, and my son. You never cease to amaze and inspire me. Your creativity exceeds my own. To Gracie, for being my happy “Pretty Princess.” Thank you for allowing me to see the world through the eyes of a nature-loving little girl.