Dirty Harry and the Real Constitution Michael Stokes Paulsent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stirling Silliphant Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2f59n87r No online items Finding Aid for the Stirling Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Finding aid prepared by Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 14 August 2017 Finding Aid for the Stirling PASC.0134 1 Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Title: Stirling Silliphant papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0134 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 27.0 linear feet65 boxes. Date (inclusive): ca. 1950-ca. 1985 Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Stirling Silliphant Papers (Collection Number PASC 134). -

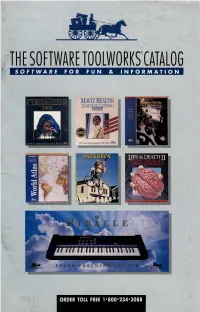

Thf SO~Twarf Toolworks®Catalog SOFTWARE for FUN & INFORMATION

THf SO~TWARf TOOlWORKS®CATAlOG SOFTWARE FOR FUN & INFORMATION ORDER TOLL FREE 1•800•234•3088 moni tors each lesson and builds a seri es of personalized exercises just fo r yo u. And by THE MIRACLE PAGE 2 borrowi ng the fun of vid eo ga mes, it Expand yo ur repertoire ! IT'S AMIRAClf ! makes kids (even grown-up kids) want to The JI!/ irac/e So11g PAGE 4 NINT!NDO THE MIRACLE PIANO TEACHING SYSTEM learn . It doesn't matter whether you 're 6 Coflectioll: Vo/11111e I ~ or 96 - The Mirttcle brings th e joy of music adds 40 popular ENT!RTA INMENT PAGE/ to everyo ne. ,.-~.--. titles to your The Miracle PiC1110 PRODUCTI VITY PAGE 10 Tet1dti11gSyste111, in cluding: "La Bamba," by Ri chi e Valens; INFORMATION PAGElJ "Sara," by Stevie Nicks; and "Thi s Masquerade," by Leon Russell. Volume II VA LU EP ACKS PAGE 16 adds 40 MORE titles, including: "Eleanor Rigby," by John Lennon and Paul McCartney; "Faith," by George M ichael; Learn at your own pace, and at "The Girl Is M in e," by Michael Jackson; your own level. THESE SYMBOLS INDICATE and "People Get Ready," by C urtis FORMAT AVAILABILITY: As a stand-alone instrument, The M irt1de Mayfield. Each song includes two levels of play - and learn - at yo ur own rivals the music industry's most sophis playin g difficulty and is full y arra nged pace, at your own level, NIN TEN DO ti cated MIDI consoles, with over 128 with complete accompaniments for a truly ENTERTAINMENT SYST!M whenever yo u want. -

Dirty Harry Quand L’Inspecteur S’En Mêle Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 Minutes Pascal Grenier

Document generated on 09/25/2021 3:09 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Dirty Harry Quand l’inspecteur s’en mêle Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 minutes Pascal Grenier Animer ailleurs Number 259, March–April 2009 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/44930ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Grenier, P. (2009). Review of [Dirty Harry : quand l’inspecteur s’en mêle / Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 minutes]. Séquences, (259), 32–32. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2009 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 3 ARRÊT SUR IMAGE I FLASH-BACK Dirty Harry I Quand l'inspecteur s'en mêle Un inspecteur aux méthodes expéditives lutte contre un psychopathe dangereux qui menace la population de San Francisco. Sorti en 1971, ce drame policier fort percutant créa toute une controverse à l'époque. Clint Eastwood est propulsé au rang de star et son personnage, plus grand que nature, est encore aujourd'hui une véritable icône cinématographique. PASCAL GRENIER irty Harry marque la quatrième collaboration entre le réalisateur Don Siegel et le comédien Clint Eastwood D après Coogan's Bluff, Two Mules for Sister Sara et The Beguiled. -

Ant CARTOLINA 12Luglio 150X

Bologna, Sotto dal 4 luglio al 1° settembre le stelle Piazza Maggiore e BarcArena del Cinema ore 21.30 molte coscienze, trasformando il film in terreno di scontro. La stroncatura Domenica 12 luglio 2020 più celebre, dell’influentissima Pauline Kael, bollava senza mezzi termini Dirty Harry come apologia del fascismo. [...] Serata promossa da L’infuocato dibattito ideologico attorno al film si comprende meglio se in- serito nel clima dell’epoca, segnato da rivolte studentesche, cultura hippy sulla cresta dell’onda, guerra in Vietnam vicina allo sfascio: Ispettore Cal- Polizieschi urbani laghan emerge come oggetto scomodo, in cui si afferma il desiderio di un punto fermo virile e forcaiolo in mezzo alle incertezze sociali. Al tempo ISPETTORE CALLAGHAN: stesso, la figura di Callaghan si staglia come angelo della vendetta fuori IL CASO SCORPIO È TUO dalla storia, attraversato da pulsioni di morte eterne e universali. Il detecti- ve di Eastwood, insomma, sembra trarre forza dal convergere di un alone (Dirty Harry, USA/1971) mitizzante e di un tratteggio realistico preciso, in un’oscillazione che con- tribuisce ad arricchire la complessa riflessione sulla violenza che altri film, Regia: Don Siegel. Soggetto: Harry Julian Fink, Rita M. Fink. Sceneggiatura: nello stesso 1971, stanno intraprendendo: Il braccio violento della legge di Harry Julian Fink, Rita M. Fink, Dean Riesner. Fotografia: Bruce Surtees. William Friedkin, Cane di paglia e Arancia meccanica. Ispettore Callaghan, Montaggio: Carl Pingitore. Scenografia: Dale Hennesy. Musica: Lalo in particolare, insiste sulla dimensione urbana del fenomeno. Schifrin. Interpreti: Clint Eastwood (Harry Callahan), Harry Guardino Ferme restando le posizioni etiche dei vari commentatori, quasi tutti si (Bressler), Andy Robinson (Scorpio), Reni Santoni (Chico Sanchez), John sono trovati d’accordo sulla potenza visiva e narrativa del film, tra gli esiti Vernon (il sindaco), John Larch (il capo della polizia), John Mitchum più alti di un regista che ha sempre fatto dell’efficacia una virtù stilistica. -

Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20Th Century

1632 MARKET STREET SAN FRANCISCO 94102 415 347 8366 TEL For immediate release Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century Curated by Ralph DeLuca July 21 – September 24, 2016 FraenkelLAB 1632 Market Street FraenkelLAB is pleased to present Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters of the 20th Century, curated by Ralph DeLuca, from July 21 through September 24, 2016. Beginning with the earliest public screenings of films in the 1890s and throughout the 20th century, the design of eye-grabbing posters played a key role in attracting moviegoers. Bullitt, Blow-Up, & Other Dynamite Movie Posters at FraenkelLAB focuses on seldom-exhibited posters that incorporate photography to dramatize a variety of film genres, from Hollywood thrillers and musicals to influential and experimental films of the 1960s-1990s. Among the highlights of the exhibition are striking and inventive posters from the mid-20th century, including the classic films Gilda, Niagara, The Searchers, and All About Eve; Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho; and B movies Cover Girl Killer, Captive Wild Woman, and Girl with an Itch. On view will be many significant posters from the 1960s, such as Russ Meyer’s cult exploitation film Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!; Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up; a 1968 poster for the first theatrical release of Un Chien Andalou (Dir. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, 1928); and a vintage Japanese poster for Buñuel’s Belle de Jour. The exhibition also features sensational posters for popular movies set in San Francisco: the 1947 film noir Dark Passage (starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall); Steve McQueen as Bullitt (1968); and Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry (1971). -

Allen Rostron, the Law and Order Theme in Political and Popular Culture

OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 FALL 2012 NUMBER 3 ARTICLES THE LAW AND ORDER THEME IN POLITICAL AND POPULAR CULTURE Allen Rostron I. INTRODUCTION “Law and order” became a potent theme in American politics in the 1960s. With that simple phrase, politicians evoked a litany of troubles plaguing the country, from street crime to racial unrest, urban riots, and unruly student protests. Calling for law and order became a shorthand way of expressing contempt for everything that was wrong with the modern permissive society and calling for a return to the discipline and values of the past. The law and order rallying cry also signified intense opposition to the Supreme Court’s expansion of the constitutional rights of accused criminals. In the eyes of law and order conservatives, judges needed to stop coddling criminals and letting them go free on legal technicalities. In 1968, Richard Nixon made himself the law and order candidate and won the White House, and his administration continued to trumpet the law and order theme and blame weak-kneed liberals, The William R. Jacques Constitutional Law Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. B.A. 1991, University of Virginia; J.D. 1994, Yale Law School. The UMKC Law Foundation generously supported the research and writing of this Article. 323 OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM 324 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. 37 particularly judges, for society’s ills. -

2. Express Yourself 1. Assess Your Thoughts

WHAT’S THE BIG IDEA? Live better every day 6 WAYS TO TURN YOUR FUZZY THOUGHTS INTO A CRYSTAL-CLEAR CONCEPT 1. ASSESS YOUR THOUGHTS If the right words escape you, you’re acting like a Stifled Forecaster. Look at your idea from three different angles. 1. Zoom out by filling in the blanks. This idea will help/improve/fix . This idea will help these people: . The best part of this idea is . 2. Create a mash-up with Hollywood shorthand. RoboCop has been described as Terminator meets Dirty Harry. Flashdance was Rocky for women. West Side Story is Romeo and Juliet with singing and dancing (and no tights). Got the gist? Try this with your idea (pop culture references not required). 3. Bust your assumptions. We all assume things that subconsciously shape our thoughts — truths that may or may not be true. Write down the assumptions around your idea. Ponder them. Keep, adjust, or throw them away. OR If your idea is too big for words, you’re acting like an Expansive Forecaster. Here’s how to surface your core concept. Come up with a list of must-haves for your idea. For instance: • Needs to achieve X. • Costs no more than X. • Focuses on the topic of X. • Must happen by X. 2. E XPRESS YOURSELF Next, look at all your brainstorms (it helps to write them down) to see if they meet your must-have requirements. If they’re nice-to-haves, put them aside for later. Briefly and clearly write or record your Then, organize your must-have thoughts to see if you recognize your original idea. -

1-Abdul Haseeb Ansari

Journal of Criminal Justice and Law Review : Vol. 1 • No. 1 • June 2009 IDENTIFYING LARGE REPLICABLE FILM POPULATIONS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE FILM RESEARCH: A UNIFIED FILM POPULATION IDENTIFICATION METHODOLOGY FRANKLIN T. WILSON Indiana State University ABSTRACT: Historically, a dominant proportion of academic studies of social science issues in theatrically released films have focused on issues surrounding crime and the criminal justice system. Additionally, a dominant proportion has utilized non-probability sampling methods in identifying the films to be analyzed. Arguably one of the primary reasons film studies of social science issues have used non-probability samples may be that no one has established definitive operational definitions of populations of films, let alone develop datasets from which researchers can draw. In this article a new methodology for establishing film populations for both qualitative and quantitative research–the Unified Film Population Identification Methodology–is both described and demonstrated. This methodology was created and is presented here in hopes of expand the types of film studies utilized in the examination of social science issues to those communication theories that require the examination of large blocks of media. Further, it is anticipated that this methodology will help unify film studies of social science issues in the future and, as a result, increase the reliability, validity, and replicability of the said studies. Keywords: UFPIM, Film, Core Cop, Methodology, probability. Mass media research conducted in the academic realm has generally been theoretical in nature, utilizing public data, with research agendas emanating from the academic researchers themselves. Academic studies cover a gambit of areas including, but not limited to, antisocial and prosocial effects of specific media content, uses and gratifications, agenda setting by the media, and the cultivation of perceptions of social reality (Wimmer & Dominick, 2003). -

Don Siegel Rétrospective 3 Septembre - 12 Octobre

DON SIEGEL RÉTROSPECTIVE 3 SEPTEMBRE - 12 OCTOBRE AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE WARNER BROS. L’Inspecteur Harry LE ROUGE EST LA COULEUR DE LA PITIÉ JEAN-FRANÇOIS RAUGER Né à Chicago en 1912, Don Siegel débute dans le cinéma en occupant plusieurs postes à la Warner Bros. avant de se spécialiser dans le montage. Il signe sa première réalisation en 1946 et, passant d’un studio à l’autre, alterne les genres (films noirs, westerns, science-fiction). Il se distingue par son traitement de la violence, la sécheresse de ses scènes d’action et le refus d’une psychologie conventionnelle. À partir de 1968, il réa- lise cinq films avec Clint Eastwood en vedette, contribuant à la fabrication de son personnage et s’inscrivant dans une certaine modernité du cinéma hollywoodien. S’il fallait associer Don Siegel à une génération particu- tout) dans le cinéma de Don Siegel ramène en effet à lière de cinéastes américains, il faudrait le rapprocher ce onzième long métrage. de ces réalisateurs qui, à partir de l’immédiat après- Les habitants d’une petite ville de Californie sont trans- guerre, ont été tout à la fois la cause et le produit d’une formés, après une invasion extraterrestre, en créatures crise ainsi que d’une remise en question du système sans affects, qui conservent l’apparence extérieure de hollywoodien et de son idéologie. C’est l’heure des ceux dont elles ont volé l’enveloppe corporelle. Dès auteurs affirmés, de ceux qui menacent l’équilibre clas- lors, les caractéristiques même de ce qui constitue sique par une manière de romantisme (Nicholas Ray), l’humanité se décollent de ce qui reste lorsqu’elle ne une énergie brutale et paradoxale (Samuel Fuller), la se réduit plus qu’à une silhouette. -

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This List Was Created to Make It Easier for Customers to Figure out What Type of NVRAM They Need for Each Machine

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This list was created to make it easier for customers to figure out what type of NVRAM they need for each machine. Please consult the product pages at www.pinitech.com for each type of NVRAM for further information on difficulty of installation, any jumper changes necessary on your board(s), a diagram showing location of the RAM being replaced & more. *NOTE: This list is meant as quick reference only. On Williams WPC and Sega/Stern Whitestar games you should check the RAM currently in your machine since either a 6264 or 62256 may have been used from the factory. On Williams System 11 games you should check that the chip at U25 is 24-pin (6116). See additional diagrams & notes at http://www.pinitech.com/products/cat_memory.php for assistance in locating the RAM on your board(s). PLUG-AND-PLAY (NO SOLDERING) Games below already have an IC socket installed on the boards from the factory and are as easy as removing the old RAM and installing the NVRAM (then resetting scores/settings per the manual). • BALLY 6803 → 6116 NVRAM • SEGA/STERN WHITESTAR → 6264 OR 62256 NVRAM (check IC at U212, see website) • DATA EAST → 6264 NVRAM (except Laser War) • CLASSIC BALLY → 5101 NVRAM • CLASSIC STERN → 5101 NVRAM (later Stern MPU-200 games use MPU-200 NVRAM) • ZACCARIA GENERATION 1 → 5101 NVRAM **NOT** PLUG-AND-PLAY (SOLDERING REQUIRED) The games below did not have an IC socket installed on the boards. This means the existing RAM needs to be removed from the board & an IC socket installed. -

Movie Heroes and the Heroic Journey

LESSON PLAN Level: Grades 11-12 About the Author: Adapted from the The AML Anthology. Supplement (1992), produced by the Association for Media Literacy. By Don Walker, Metropolitan Toronto Separate School Board and Leslie Johnstone, York Region Board of Education Movie Heroes and the Heroic Journey Overview The place of the hero in our modern lives is a site of struggle. On the one hand, the hero's quest can have meanings for individuals who seek to understand their own journey through life. On the other hand, the hero can be seen as a repository of those values esteemed by the society. The study of the hero as social icon offers the student an opportunity to reflect on and critique the dominant reading of the hero, as well as to consider oppositional readings. In this lesson, students will be introduced to the work of Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell and will have the opportunity to apply these theories to the examination of heroes. (Note: Teachers should replace any movies and heroic figures who no longer seem relevant with more recent examples.) Objectives To enable students to: differentiate between a classical hero, modern hero and a celebrity. identify the stages of the heroic quest. identify the dominant ideology of the culture as exemplified by a hero, and to negotiate an oppositional reading. see the application of the quest motif to their own lives. understand the role of the villain as the dark side of the hero, and the repository or reflection of the fears and concerns of society. appreciate variations of the heroic journey in different film genres. -

24-35 Top 50 0705

MAY contents volume 56/number 9 COVERSTORY With digital technologies occupying increasing space in our minds and lives, it’s no surprise that many of this year’s award winners took honors for innovations in the areas of marketing and merchandising, or that a number aligned themselves with another big trend that is making waves as technology makes more things possible: mass one-to-one customization. We say kudos to all of Apparel’s innovators, who continue to move the industry forward in interesting and unexpected ways. BY JORDAN K. SPEER, JESSICA BINNS AND DEENA M. AMATO-MCCOY Cover photography courtesy of Kokatat, Photo credit Jordy Searle INNOVATOR . .PAGE INNOVATOR . .PAGE Acustom Apparel . .17 Kokatat . .42 Aerosoles . .10 Koos Manufacturing . .21 Ascena Retail Group . .38 L. L. Bean . .22 Betabrand . .18 Lands' End Business Outfitters . .12 Brooks Brothers . .24 Macy's . .26 Buffalo Exchange . .34 Mitchells . .33 bumbrella . .37 Mizuno Running . .19 Canada Goose . .36 Mountain Equipment Co-op . .29 Chico's . .13 Performance Scrubs . .32 Dragon Crowd . .9 Rebecca Minkoff . .9 Everything But Water . .26 RG Barry . .41 Francesca's . .41 Stantt . .36 Garmatex . .17 SustainU . .33 Harry Rosen . .23 Timberland . .14 Hatley . .43 Topson Downs . .44 in the pink . .11 Twice as Nice Uniforms . .28 JustFab . .30 Under Armour . .21 Kathmandu . .20 Vestagen Technical Textiles . .15 TOP INNOVATOR SPONSORS BY JORDAN K. SPEER, JESSICA BINNS AND DEENA M. AMATO-MCCOY With digital technologies occupying increasing space in our minds and lives, it’s no surprise that many of this year’s award winners took honors for innovations in the areas of marketing and merchandising, or that a number aligned themselves with another big trend that is making waves as technology makes more things possible: mass one-to-one customization.