Sam Peckinpah Killed Randolph Scott (But Somehow the Duke Survived)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noviembre 2010

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 913691125 (taquilla) Fax: 91 4672611 913692118 [email protected] (gerencia) http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html Fax: 91 3691250 NIPO (publicación electrónica) :554-10-002-X MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala noviembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2010 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 16.15 - 00.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.00 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico NOVIEMBRE 2010 Don Siegel (y II) III Muestra de cine coreano (y II) VIII Mostra portuguesa Cine y deporte (III) I Ciclo de cine y archivos Muestra de cine palestino de Madrid Premios Goya (II) Buzón de sugerencias: Hayao Miyazaki Cine para todos Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. -

Stirling Silliphant Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2f59n87r No online items Finding Aid for the Stirling Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Finding aid prepared by Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 14 August 2017 Finding Aid for the Stirling PASC.0134 1 Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Title: Stirling Silliphant papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0134 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 27.0 linear feet65 boxes. Date (inclusive): ca. 1950-ca. 1985 Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Stirling Silliphant Papers (Collection Number PASC 134). -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Filabres-Alhamilla

Guide Tourist-Cinematographic Route Filabres-Alhamilla SCENE TAKE Una Comarca de cine... Guide Tourist-Cinematographic Route Filabres-Alhamilla In memory of the movie world in Almeria as a prime cultural legacy and a present and future tourist asset. To all the tourists and visitors who want to enjoy a region full of light, colours and originality. Promoted and edited by Commonwealth of Municipalities for the Development of Interior Towns Idea and general coordination José Castaño Aliaga, manager of the Tourist Plan of Filabres-Alhamilla Malcamino’s Route design, texts, documentation, tourist information, stills selection, locations, docu- mentary consultancy, Road Book creation, maps and GPS coordinates. Malcamino’s Creative direction www.oncepto.com Design and layout Sonja Gutiérrez Front-page picture Sonja Gutiérrez Printing Artes Gráficas M·3 Legal deposit XXXXXXX Translation Itraductores Acknowledgement To all the municipalities integrated in the Commonwealth of Municipalities for the De- velopment of Interior Towns: Alcudia de Monteagud, Benitagla, Benizalón, Castro de Fi- labres, Lucainena de las Torres, Senés, Tabernas, Tahal, Uleila del Campo and Velefique Documentation and publications for support and/or interest Almería, Plató de Cine – Rodajes Cinematográficos (1951-2008) – José Márquez Ubeda (Diputación Provincial de Almería) Almería, Un Mundo de Película – José Enrique Martínez Moya (Diputación Provincial de Almería) Il Vicino West – Carlo Gaberscek (Ribis) Western a la Europea, un plato que se sirve frio – Anselmo Nuñez Marqués (Entrelíneas Editores) La Enciclopedia de La Voz de Almería Fuentes propias de Malcamino’s Reference and/or interest Webs www.mancomunidadpueblosdelinterior.es www.juntadeandalucia.es/turismocomercioydeporte www.almeriaencorto.es www.dipalme.org www.paisajesdecine.com www.almeriaclips.com www.tabernasdecine.es www.almeriacine.es Photo: Sonja Gutiérrez index 9 Prologue “Land of movies for ever and ever.. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Sydney Program Guide

Firefox http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repor... SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 10th January 2021 06:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 06:30 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:30 am Key Of David PG The Key of David, a religious program, covers important issues of today with a unique perspective. 08:00 am Bondi Rescue Kathmandu Coast To CC PG Bondi Rescue Kathmandu Coast To Coast Coast (Rpt) Coarse Language The team from Bondi Rescue head to New Zealand to take on the legendary Kathmandu Coast to Coast Race - an epic 3 day adventure race from one side of the country to the other. 09:00 am Rocky Mountain Railroad (Rpt) PG Tunnel To Hell Mild Coarse Two elite crews battle brutal weather and deadly terrain in order keep Language two critical railroads rolling to deliver crucial freight and passengers through the Rocky Mountains and to the remote Arctic. 10:00 am Rocky Mountain Railroad (Rpt) PG Deadly Washout Mild Coarse Two elite crews battle brutal weather and deadly terrain in order keep Language two critical railroads rolling to deliver crucial freight and passengers through the Rocky Mountains and to the remote Arctic. 11:00 am Mega Mechanics (Rpt) G What happens when mega-machines go down? It's up to the mega- mechanics to fix them! With huge structures, extreme locations & millions of dollars on the line if they don't repair the machines on time. 12:00 pm One Strange Rock (Rpt) CC PG Storm Mature Themes Ever wonder how our planet got here? Earth is a very lucky planet. -

Sample Ballot and Voter Information Pamphlet Format

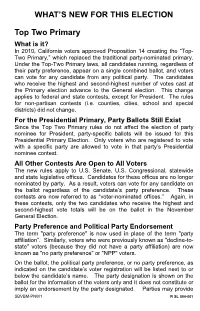

WHAT’S NEW FOR THIS ELECTION Top Two Primary What is it? In 2010, California voters approved Proposition 14 creating the “Top- Two Primary,” which replaced the traditional party-nominated primary. Under the Top-Two Primary laws, all candidates running, regardless of their party preference, appear on a single combined ballot, and voters can vote for any candidate from any political party. The candidates who receive the highest and second-highest number of votes cast at the Primary election advance to the General election. This change applies to federal and state contests, except for President. The rules for non-partisan contests (i.e. counties, cities, school and special districts) did not change. For the Presidential Primary, Party Ballots Still Exist Since the Top Two Primary rules do not affect the election of party nominee for President, party-specific ballots will be issued for this Presidential Primary Election. Only voters who are registered to vote with a specific party are allowed to vote in that party’s Presidential nominee contest. All Other Contests Are Open to All Voters The new rules apply to U.S. Senate, U.S. Congressional, statewide and state legislative offices. Candidates for these offices are no longer nominated by party. As a result, voters can vote for any candidate on the ballot regardless of the candidate’s party preference. These contests are now referred to as “voter-nominated offices.” Again, in these contests, only the two candidates who receive the highest and second-highest vote totals will be on the ballot in the November General Election. Party Preference and Political Party Endorsement The term "party preference" is now used in place of the term "party affiliation”. -

Dirty Harry Quand L’Inspecteur S’En Mêle Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 Minutes Pascal Grenier

Document generated on 09/25/2021 3:09 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Dirty Harry Quand l’inspecteur s’en mêle Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 minutes Pascal Grenier Animer ailleurs Number 259, March–April 2009 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/44930ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Grenier, P. (2009). Review of [Dirty Harry : quand l’inspecteur s’en mêle / Dirty Harry, États-Unis 1971, 102 minutes]. Séquences, (259), 32–32. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2009 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 3 ARRÊT SUR IMAGE I FLASH-BACK Dirty Harry I Quand l'inspecteur s'en mêle Un inspecteur aux méthodes expéditives lutte contre un psychopathe dangereux qui menace la population de San Francisco. Sorti en 1971, ce drame policier fort percutant créa toute une controverse à l'époque. Clint Eastwood est propulsé au rang de star et son personnage, plus grand que nature, est encore aujourd'hui une véritable icône cinématographique. PASCAL GRENIER irty Harry marque la quatrième collaboration entre le réalisateur Don Siegel et le comédien Clint Eastwood D après Coogan's Bluff, Two Mules for Sister Sara et The Beguiled. -

Five Online Sources Reviewed

OLAC CAPC Moving Image Work-Level Records Task Force Final Report and Recommendations August 21, 2009 Amended August, 28, 2009 to change Scarlet to Scarlett Part IV: Extracting Work-Level Information from Existing MARC Manifestation Records Appendix: Comparison of Selected Extracted MARC Data with External Sources Task Force Members: Kelley McGrath (chair; subgroup 1 and 4 leader) Susannah Benedetti (subgroup 2) Lynne Bisko (subgroup 4) Greta de Groat (subgroup 1) Ngoc-My Guidarelli (subgroup 2) Jeannette Ho (subgroup 2 leader) Nancy Lorimer (subgroup 1) Scott Piepenburg (subgroup 3) Thelma Ross (subgroup 3 leader) Walt Walker (subgroup 3) Karen Gorss Benko (subgroup 3, 2008) Scott M. Dutkiewicz (subgroup 4, 2008) Advisors to the Task Force: David Miller Jay Weitz Martha Yee Titles Reviewed We reviewed ten titles. These ten works were found in eighty-three records in our sample dataset. These represent primarily major feature films as those are the materials for which there are most likely to be reliable, independent secondary sources of information. The titles include several English language American film releases, one non-English Roman alphabet title, three non-English, non-Roman alphabet titles, and one English language television documentary. The dates of the works range from 1931 to 2001. Five Online Sources Reviewed We selected five reliable, comprehensive online sources to review. We did not use a print source as a sufficiently comprehensive one was not conveniently available to us at the time of the review. 1 of 13 1. allmovie (AMG) http://allmovie.com/ Contains over 220,000 titles. Includes information from a variety of sources, including video packaging, promotional materials, press releases, watching the movies, etc. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Rio Bravo (1959) More Secure Surroundings, and Then the Hired Guns Come In, Waiting Around for Their Chance to Break Him out of Jail

already have working for him. Burdette's men cut the town off to prevent Chance from getting Joe into Rio Bravo (1959) more secure surroundings, and then the hired guns come in, waiting around for their chance to break him out of jail. Chance has to wait for the United States marshal to show up, in six days, his only help from Stumpy (Walter Brennan), a toothless, cantankerous old deputy with a bad leg who guards the jail, and Dude (Dean Martin), his former deputy, who's spent the last two years stumbling around in a drunken stupor over a woman that left him. Chance's friend, trail boss Pat Wheeler (Ward Bond), arrives at the outset of the siege and tries to help, offering the services of himself and his drovers as deputies, which Chance turns down, saying they're not professionals and would be too worried about their families to be good at anything except being targets for Burdette's men; but Chance does try to enlist the services of Wheeler's newest employee, a callow- looking young gunman named Colorado Ryan (Ricky Nelson), who politely turns him down, saying he prefers to mind his own business. In the midst of all of this tension, Feathers (Angie Dickinson), a dance hall entertainer, arrives in town and nearly gets locked up by Chance for cheating at cards, until he finds out that he was wrong and that she's not guilty - - this starts a verbal duel between the two of them Theatrical release poster (Wikipedia) that grows more sexually intense as the movie progresses and she finds herself in the middle of Chance's fight.