Behind-The-Screens-Transcript.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

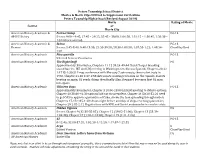

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

AOL & Time Warner: How the “Deal of a Century” Was Over in a Decade

AOL & Time Warner: How the “Deal of a Century” Was Over in a Decade A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Roberta W. Harrington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Television Management May 2013 i © Copyright 2013 Roberta W. Harrington. All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor for the Television Management program, Mr. Al Tedesco for teaching me to literally think outside the “box” when it comes to the television industry. I’d also like to thank my thesis advisor Mr. Phil Salas, as well as my classmates for keeping me on my toes, and for pushing me to do my very best throughout my time at Drexel. And to my Dad, who thought my quitting a triple “A” company like Bloomberg to work in the television industry was a crazy idea, but now admits that that was a good decision for me…I love you and thank you for your support! iii Table of Contents ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………… iv 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………................6 1.1 Statement of the Problem…………………………………………………………7 1.2 Explanation of the Importance of the Problem……………………………………9 1.3 Purpose of the Study………………………………………………………………10 1.4 Research Questions……………………………………………………….............10 1.5 Significance to the Field………………………………………………….............11 1.6 Definitions………………………………………………………………………..11 1.7 Limitations………………………………………………………………………..12 1.8 Ethical Considerations……………………………………………………………12 2. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE………………………………………………..14 2.1 Making Sense of the Information Superhighway…………………………………14 2.2 Case Strikes……………………………………………………………………….18 2.3 The Whirlwind Begins…………………………………………………………....22 2.4 Word on the Street………………………………………………………………..25 2.5 The Announcement…………………………………………………………….....26 2.6 Gaining Regulatory Approval………………………………………………….....28 2.7 Mixing Oil with Water……………………………………………………………29 2.8 The Architects………………………………………………………………….....36 2.9 The Break-up and Aftermath……………………………………………………..46 3. -

Digital Dialectics: the Paradox of Cinema in a Studio Without Walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , Vol

Scott McQuire, ‘Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 19, no. 3 (1999), pp. 379 – 397. This is an electronic, pre-publication version of an article published in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television is available online at http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=g713423963~db=all. Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls Scott McQuire There’s a scene in Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, Paramount Pictures; USA, 1994) which encapsulates the novel potential of the digital threshold. The scene itself is nothing spectacular. It involves neither exploding spaceships, marauding dinosaurs, nor even the apocalyptic destruction of a postmodern cityscape. Rather, it depends entirely on what has been made invisible within the image. The scene, in which actor Gary Sinise is shown in hospital after having his legs blown off in battle, is noteworthy partly because of the way that director Robert Zemeckis handles it. Sinise has been clearly established as a full-bodied character in earlier scenes. When we first see him in hospital, he is seated on a bed with the stumps of his legs resting at its edge. The assumption made by most spectators, whether consciously or unconsciously, is that the shot is tricked up; that Sinise’s legs are hidden beneath the bed, concealed by a hole cut through the mattress. This would follow a long line of film practice in faking amputations, inaugurated by the famous stop-motion beheading in the Edison Company’s Death of Mary Queen of Scots (aka The Execution of Mary Stuart, Thomas A. -

Corgi™ Manual

1 The Phantom Laboratory Corgi™ Manual Copyright © 2020 WARRANTY THE PHANTOM LABORATORY INCORPORATED (“Seller”) warrants that this product shall remain in good working order and free of all material defects for a period of one (1) year following the date of purchase. If, prior to the expiration of the one (1) year warranty period, the product becomes defective, Buyer shall return the product to the Seller at: ByTruck ByMail The Phantom Laboratory,Incorporated The Phantom Laboratory,Incorporated 2727StateRoute29 POBox511 Greenwich,NY12834 Salem,NY12865-0511 Seller shall, at Seller’s sole option, repair or replace the defective product. The Warranty does not cover damage to the product resulting from accident or misuse. IF THE PRODUCT IS NOT IN GOOD WORKING ORDER AS WARRANTED, THE SOLE AND EXCLUSIVE REMEDY SHALL BE REPAIR OR REPLACEMENT, AT SELLER’S OPTION. IN NO EVENT SHALL SELLER BE LIABLE FOR ANY DAMAGES IN EXCESS OF THE PURCHASE PRICE OF THE PRODUCT. THIS LIMITATION APPLIES TO DAMAGES OF ANY KIND, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, DIRECT OR INDIRECT DAMAGES, LOST PROFITS, OR OTHER SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, WHETHER FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, OR WHETHER ARISING OUT OF THE USE OF OR INABILITY TO USE THE PRODUCT. ALL OTHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTY OF MERCHANT ABILITY AND FITNESS FOR PARTICULAR PURPOSE, ARE HEREBY DISCLAIMED. WARNING This product has an FH3-4 mm/min flame rating and is considered to be flammable. It is advised not to expose this product to open flame or high temperature (over 125° Celsius or 250° Fahrenheit) heating elements. -

Stirling Silliphant Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2f59n87r No online items Finding Aid for the Stirling Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Finding aid prepared by Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 14 August 2017 Finding Aid for the Stirling PASC.0134 1 Silliphant Papers, ca. 1950-ca. 1985 PASC.0134 Title: Stirling Silliphant papers Identifier/Call Number: PASC.0134 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 27.0 linear feet65 boxes. Date (inclusive): ca. 1950-ca. 1985 Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Stirling Silliphant Papers (Collection Number PASC 134). -

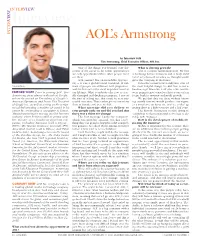

To Download a PDF of an Interview with Tim Armstrong, Chief Executive

INTERVIEW VIEW Interview INTER AOL’s Armstrong An Interview with Tim Armstrong, Chief Executive Offi cer, AOL Inc. One of the things I’ve learned over the What is driving growth? course of my career so far is that opportunities AOL is a classic turnaround story. We had are only opportunities when other people don’t a declining historic business and a fairly short see them. list of very focused activities we thought would AOL seemed like an incredible opportu- grow the company in the future. nity – it was a global brand, hundreds of mil- From the turnaround standpoint, one of Tim Armstrong lions of people use different AOL properties, the most helpful things we did was to set a and the Internet is the most important trend in timeline right when we took over – we said we EDITORS’ NOTE Prior to joining AOL, Tim our lifetime. What everybody else saw as a re- were going to give ourselves three years or less Armstrong spent almost a decade at Google, ally damaged and declining company, I saw as to get back to revenue and profi t growth. where he served as President of Google’s the start of a long race that could be very suc- We put that date out there without know- Americas Operations and Senior Vice President cessful over time. That is what got me out of my ing exactly how we would get there but it gave of Google Inc., as well as serving on the compa- chair at Google and over to AOL. us a timeframe to focus on, and we ended up ny’s global operating committee. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

Close Encounters with Creative Chemical Thinking: an Outreach Presentation Using Movie Clips About the Elemental Composition of Aliens and Extraterrestrial Minerals

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications -- Chemistry Department Published Research - Department of Chemistry 2016 Close encounters with creative chemical thinking: An outreach presentation using movie clips about the elemental composition of aliens and extraterrestrial minerals Mark A. Griep University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Marjorie L. Mikasen University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chemfacpub Part of the Analytical Chemistry Commons, Medicinal-Pharmaceutical Chemistry Commons, and the Other Chemistry Commons Griep, Mark A. and Mikasen, Marjorie L., "Close encounters with creative chemical thinking: An outreach presentation using movie clips about the elemental composition of aliens and extraterrestrial minerals" (2016). Faculty Publications -- Chemistry Department. 128. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chemfacpub/128 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Published Research - Department of Chemistry at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications -- Chemistry Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Educación Química (2016) 27, 154---162 educación Química www.educacionquimica.info CHEMISTRY DIDACTICS Close encounters with creative chemical thinking: An outreach presentation using movie clips about the elemental composition of aliens and extraterrestrial minerals ∗ Mark A. Griep , Marjorie L. Mikasen Department of Chemistry, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588-0304, USA Received 6 March 2015; accepted 17 November 2015 Available online 24 December 2015 KEYWORDS Abstract To introduce more chemistry into a middle and high school bioengineering camp experience, we developed an educational and entertaining presentation that examines the Middle school; chemistry in movies about aliens and minerals from outer space. -

System Safety Engineering: Back to the Future

System Safety Engineering: Back To The Future Nancy G. Leveson Aeronautics and Astronautics Massachusetts Institute of Technology c Copyright by the author June 2002. All rights reserved. Copying without fee is permitted provided that the copies are not made or distributed for direct commercial advantage and provided that credit to the source is given. Abstracting with credit is permitted. i We pretend that technology, our technology, is something of a life force, a will, and a thrust of its own, on which we can blame all, with which we can explain all, and in the end by means of which we can excuse ourselves. — T. Cuyler Young ManinNature DEDICATION: To all the great engineers who taught me system safety engineering, particularly Grady Lee who believed in me, and to C.O. Miller who started us all down this path. Also to Jens Rasmussen, whose pioneering work in Europe on applying systems thinking to engineering for safety, in parallel with the system safety movement in the United States, started a revolution. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: The research that resulted in this book was partially supported by research grants from the NSF ITR program, the NASA Ames Design For Safety (Engineering for Complex Systems) program, the NASA Human-Centered Computing, and the NASA Langley System Archi- tecture Program (Dave Eckhart). program. Preface I began my adventure in system safety after completing graduate studies in computer science and joining the faculty of a computer science department. In the first week at my new job, I received a call from Marion Moon, a system safety engineer at what was then Ground Systems Division of Hughes Aircraft Company. -

Café Society

Presents CAFÉ SOCIETY A film by Woody Allen (96 min., USA, 2016) Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia CAFÉ SOCIETY Starring (in alphabetical order) Rose JEANNIE BERLIN Phil STEVE CARELL Bobby JESSE EISENBERG Veronica BLAKE LIVELY Rad PARKER POSEY Vonnie KRISTEN STEWART Ben COREY STOLL Marty KEN STOTT Co-starring (in alphabetical order) Candy ANNA CAMP Leonard STEPHEN KUNKEN Evelyn SARI LENNICK Steve PAUL SCHNEIDER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON, p.g.a. STEPHEN TENENBAUM, p.g.a. EDWARD WALSON, p.g.a. Co-Producer HELEN ROBIN Executive Producers ADAM B. STERN MARC I. STERN Executive Producer RONALD L. CHEZ Cinematographer VITTORIO STORARO AIC, ASC Production Designer SANTO LOQUASTO Editor ALISA LEPSELTER ACE Costume Design SUZY BENZINGER Casting JULIET TAYLOR PATRICIA DiCERTO 2 CAFÉ SOCIETY Synopsis Set in the 1930s, Woody Allen’s bittersweet romance CAFÉ SOCIETY follows Bronx-born Bobby Dorfman (Jesse Eisenberg) to Hollywood, where he falls in love, and back to New York, where he is swept up in the vibrant world of high society nightclub life. Centering on events in the lives of Bobby’s colorful Bronx family, the film is a glittering valentine to the movie stars, socialites, playboys, debutantes, politicians, and gangsters who epitomized the excitement and glamour of the age. Bobby’s family features his relentlessly bickering parents Rose (Jeannie Berlin) and Marty (Ken Stott), his casually amoral gangster brother Ben (Corey Stoll); his good-hearted teacher sister Evelyn (Sari Lennick), and her egghead husband Leonard (Stephen Kunken). -

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies Movies Appropriate for Children: Movies Appropriate for Adults: Angels in the Outfield Admission Rear Window Anne of Green Gables Antwone Fisher Second Best Annie (both versions) Babbette’s Feast Secrets and Lies Cinderella w/Brandy & Whitney Houston Blossoms in the Dust Singing In The Rain Despicable Me Catfish & Black Bean Soldiers Sauce Despicable Me 2 Children of Paradise St. Vincent Free Willy Cider House Rules Star Wars Trilogy Harry Potter series Cinema Paradiso The 10 Commandments Kung Fu Panda (1 and 2) Citizen Kane/Zelig The Big Wedding Like Mike CoCo—The Story of CoCo The Deep End of the Lilo and Stitch Chanell Ocean Little Secrets Come Back Little Sheba The Joy Luck Club Martian Child Coming Home The Key of the Kingdom Meet the Robinsons First Person Plural The King of Masks Prince of Egypt Flirting with Disaster The Miracle Stuart Little Greystroke The Official Story Stuart Little 2 High Tide The Searchers Superman & Superman (2013) I Am Sam The Spit Fire Grill Tarzan Into the Arms of The Truman Show The Country Bears Strangers The Kid Juno Thief of Bagdad The Lost Medallion King of Hearts To Each His Own The Odd Life of Timothy Green Les Miserables White Oleander The Rescuers Down Under Lovely and Amazing Loggerheads The Jungle Book Miss Saigon Then She Found Me Orphans Immediate Family Philomena www.adoptionsupport.org .