Van Der Steen, Martijn, Van Schelven, Rogier, Van Deventer, Peter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Groningen Frontierstad Bij Het Scheiden Van De Markt

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Frontierstad bij het scheiden van de markt. Deventer Holthuis, Paul IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1993 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Holthuis, P. (1993). Frontierstad bij het scheiden van de markt. Deventer: militair, demografisch, economisch; 1578-1648. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 en, 1602, Samenvatting en besluit Berends, wartier', 85. :keningvan 'D, timmer- ., 8 maart Aan de hand van allerlei, soms beperkte gegevens is aangetoond dat Deventer 16r3. gedurende de gewelddadige periode 1578-Í648 afzakte van een aanzienliik han- mei 16zo. -

Apeldoorn / Deventer / Zutphen Profiel Cultuurregio Stedendriehoek

Apeldoorn / Deventer / Zutphen Profiel Cultuurregio Stedendriehoek 30 oktober 2018 Gezamenlijk cultuurprofiel van Apeldoorn, Deventer en Zutphen Aanleiding voor het opstellen van een Cultuurprofiel Doelstellingen • Het ministerie van OCW heeft regio’s gevraagd een profiel op te stellen • Apeldoorn, Deventer en Zutphen hebben samen de kans gegrepen om waarin steden hun gezamenlijke visie op kunst en cultuur in de regio het veld te verbinden in de ontwikkeling van een regionaal cultuurprofiel beschrijven, de uitdagingen die zij gezamenlijk zien en willen oppakken en daarmee een agenda voor gezamenlijk cultuurbeleid te creëren en de wijze waarop het landelijke en lokale cultuurbeleid en regionale • Gezien de diversiteit in karakter, bereik en samenwerking in de disciplines samenwerking kunnen bijdragen aan oplossingen hiervoor is gekozen voor een gelaagde, gedifferentieerde aanpak. Dit profiel geeft • Met behulp van deze profielen kunnen het rijk en lagere overheden beter dan ook niet een compleet beeld, maar wel kwaliteiten en keuzes rekening houden met de samenstelling en de behoefte van de bevolking, • Dankzij dit profiel en de beleidsmaatregelen van de overheden die volgen met de identiteit en verhalen uit de regio en met het lokale klimaat voor kunnen bestaande samenwerkingsverbanden een impuls krijgen en de makers en kunstenaars in de verschillende disciplines nieuwe initiatieven, ook bovenregionaal, tot bloei worden gebracht Proces Resultaat • Binnen het Landsdeel Oost hebben gemeenten met provincies bepaald Dit Regionaal Cultuurprofiel bestaat uit vijf programmalijnen die samen de hoe de regionale cultuurprofielen in beeld konden worden gebracht agenda vormen voor samenwerking in onze regio en met andere regio’s: • DSP heeft een verkenning verricht voor Apeldoorn, Deventer en Zwolle A. -

Dashboard Statenvoorstel

Dashboard Statenvoorstel Datum GS-kenmerk Inlichtingen bij 21 november 2017 2017/0410970 M ten Heggeler, telefoon 038-499 78 64 e-mail: [email protected] Titel/Onderwerp PS kenmerk Topwerklocaties in West-Overijssel en PS/2017/798 procesfinanciering vervolgaanpak Omschrijving van besluit of onderwerp: GS hebben in opdracht van PS 5 topwerklocaties geselecteerd in West-Overijssel. GS stellen voor aan PS om deze locaties vast te stellen en op te nemen in de Omgevingsvisie bij de eerstvolgende actualisatie. Tevens worden PS gevraagd in te stemmen met de vervolgaanpak topwerklocaties West-Overijssel en de financiering ervan. Participatieladder Vorm van participatie (Rol van participant) Bestuursstijl (Rol van het bestuur) Initiatiefnemer, Beleidseigenaar, Bevoegd gezag Faciliterende stijl Samenwerkingspartner Samenwerkende stijl Medebeslisser Delegerende stijl Adviseur inspraak Participatieve stijl Adviseur eindspraak Consultatieve stijl Toeschouwer, Ontvanger informatie, Informant Open autoritaire stijl Geen rol Gesloten autoritaire stijl Wat wilt u van PS: Fase van het onderwerp/besluit: : Ter kennis geven Informerend Overleg Verkennend Brainstorm Mede-ontwerp/coproductie Samenwerking Besluitvormend Besluitvorming Inspraak Reflectie Uitvoerend Overig, namelijk: Evaluatie Reflectie Overig, namelijk: Toekomstige activiteiten Relevante achtergrondinformatie Als PS instemmen met de financiering van de Advies expertgroep topwerklocaties West-Overijssel, vervolguitvoering kan daarmee worden gestart. Omgevingsvisie paragraaf topwerklocaties -

De NS Wandeling Ijsselvallei

Wandelnet IJsselvallei dag 1 & 2 Startpunt voor wandelend Nederland NS-wandeling Zutphen – Deventer Inleiding Markering van de route Wandelnet heeft in samenwerking met NS een serie U volgt de geel-rode markering van het Hanzestedenpad. De wandelingen van station naar station samengesteld. Deze markering vindt u op een hek, lantaarnpaal of op paaltjes NS-wandelingen volgen een gedeelte van een Lange-Afstand- van wandelnetwerk Salland. Er is vooral daar gemarkeerd Wandelpad (LAW). De tweedaagse route IJsselvallei volgt waar twijfel over de juiste route zou kunnen ontstaan. een deel van het Hanzestedenpad (Streekpad 11, Doesburg– Waar routebeschrijving en markering verschillen, blijft u de Kampen 122 km). De eerste dag loopt u in 18 km van station markering volgen. Tussentijdse veranderingen in het terrein Zutphen naar Deventer. De tweede dag, van Deventer naar worden zo ondervangen. De markering van het pad wordt station Olst, is 14 km. Uiteraard is het ook mogelijk om alleen onderhouden door vrijwilligers van Wandelnet. dag 1 of alleen dag 2 te lopen. Bij (extreem) hoogwater in de IJssel zijn enkele delen van Wandelnet de route niet begaanbaar; alternatieven zijn op de kaart In ons land zijn circa 40 Lange-Afstand-Wandelpaden® weergegeven (met onderbroken lijn). (LAW's), in lengte variërend van 80 tot 725 km, beschreven Veel wandelplezier! en gemarkeerd. Alle activiteiten op het gebied van LAW's in Nederland worden gecoördineerd door Wandelnet. Naast het Heen- en terugreis ontwikkelen en beheren van LAW's behartigt Wandelnet de Station Zutphen (begin route dag 1) is per trein bereikbaar belangen van alle recreatieve wandelaars op lokaal, regionaal vanaf Deventer/Zwolle, Arnhem/Nijmegen/Roosendaal, en en landelijk niveau. -

Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland

Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland Woonakkoord Oost Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland Met trots bieden we u het Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland aan en nodigen het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties uit samen hieraan verder te bouwen. Een akkoord dat de steden Arnhem en Nijmegen, de regio’s Zwolle-Deventer- Enschede en Arnhem-Nijmegen-FoodValley/Ede en de provincies Overijssel en Gelderland met het Rijk willen sluiten. We zijn blij dat het Rijk de grote urgentie van de woningbouwopgave in Oost-Nederland ziet en daar met ons op verder wil bouwen. We willen in genoemde steden en regio’s in de komende 5 jaar 75.000 woningen bijbouwen voor starters, doorstromers en alleenstaanden. We zijn bereid om naar innovatieve en flexibele bouwwijzen en verstedelijking te kijken om snel en slim mensen van een huis te voorzien. De Randstad verschuift naar het Oosten Alleen al vanuit de Randstad verwachten we de komende 5 jaar zo’n 60.000 nieuwe huishoudens in het oosten. De verhuisstroom uit de Randstad zorgt voor een snelle verstedelijking in onze steden. Er is nog steeds een grote verhuisstroom naar de Randstad, maar dat zijn vooral jonge mensen die geen huis achter laten. De nieuwkomers vanuit de Randstad zijn vooral gezinnen en ouderen die een nieuwe woning zoeken. We delen de grote woonopgave op in een woondeal voor de steden Arnhem en Nijmegen waar de woningnood het meest urgent is en een verstedelijkingsstrategie voor de regio’s Zwolle-Deventer- Enschede en Arnhem-Nijmegen-FoodValley/Ede. Met aandacht voor de bereikbaarheid van de steden en binnen de steden. Het gaat daarbij niet alleen om weg-, spoor- en fietsverbindingen, maar ook om nieuwe vormen van mobiliteit. -

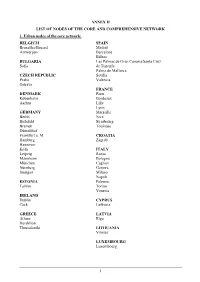

Annex Ii List of Nodes of the Core and Comprehensive Network 1

ANNEX II LIST OF NODES OF THE CORE AND COMPREHENSIVE NETWORK 1. Urban nodes of the core network: BELGIUM SPAIN Bruxelles/Brussel Madrid Antwerpen Barcelona Bilbao BULGARIA Las Palmas de Gran Canaria/Santa Cruz Sofia de Tenerife Palma de Mallorca CZECH REPUBLIC Sevilla Praha Valencia Ostrava FRANCE DENMARK Paris København Bordeaux Aarhus Lille Lyon GERMANY Marseille Berlin Nice Bielefeld Strasbourg Bremen Toulouse Düsseldorf Frankfurt a. M. CROATIA Hamburg Zagreb Hannover Köln ITALY Leipzig Roma Mannheim Bologna München Cagliari Nürnberg Genova Stuttgart Milano Napoli ESTONIA Palermo Tallinn Torino Venezia IRELAND Dublin CYPRUS Cork Lefkosia GREECE LATVIA Athina Rīga Heraklion Thessaloniki LITHUANIA Vilnius LUXEMBOURG Luxembourg 1 HUNGARY SLOVENIA Budapest Ljubljana MALTA SLOVAKIA Valletta Bratislava THE NETHERLANDS FINLAND Amsterdam Helsinki Rotterdam Turku AUSTRIA SWEDEN Wien Stockholm Göteborg POLAND Malmö Warszawa Gdańsk UNITED KINGDOM Katowice London Kraków Birmingham Łódź Bristol Poznań Edinburgh Szczecin Glasgow Wrocław Leeds Manchester PORTUGAL Portsmouth Lisboa Sheffield Porto ROMANIA București Timişoara 2 2. Airports, seaports, inland ports and rail-road terminals of the core and comprehensive network Airports marked with * are the main airports falling under the obligation of Article 47(3) MS NODE NAME AIRPORT SEAPORT INLAND PORT RRT BE Aalst Compr. Albertkanaal Core Antwerpen Core Core Core Athus Compr. Avelgem Compr. Bruxelles/Brussel Core Core (National/Nationaal)* Charleroi Compr. (Can.Charl.- Compr. Brx.), Compr. (Sambre) Clabecq Compr. Gent Core Core Grimbergen Compr. Kortrijk Core (Bossuit) Liège Core Core (Can.Albert) Core (Meuse) Mons Compr. (Centre/Borinage) Namur Core (Meuse), Compr. (Sambre) Oostende, Zeebrugge Compr. (Oostende) Core (Oostende) Core (Zeebrugge) Roeselare Compr. Tournai Compr. (Escaut) Willebroek Compr. BG Burgas Compr. -

Viral and Bacterial Infection Elicit Distinct Changes in Plasma Lipids in Febrile Children

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/655704; this version posted May 31, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Viral and bacterial infection elicit distinct changes in plasma lipids in febrile children 2 Xinzhu Wang1, Ruud Nijman2, Stephane Camuzeaux3, Caroline Sands3, Heather 3 Jackson2, Myrsini Kaforou2, Marieke Emonts4,5,6, Jethro Herberg2, Ian Maconochie7, 4 Enitan D Carrol8,9,10, Stephane C Paulus 9,10, Werner Zenz11, Michiel Van der Flier12,13, 5 Ronald de Groot13, Federico Martinon-Torres14, Luregn J Schlapbach15, Andrew J 6 Pollard16, Colin Fink17, Taco T Kuijpers18, Suzanne Anderson19, Matthew Lewis3, Michael 7 Levin2, Myra McClure1 on behalf of EUCLIDS consortium* 8 1. Jefferiss Research Trust Laboratories, Department of Medicine, Imperial College 9 London 10 2. Section of Paediatrics, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London 11 3. National Phenome Centre and Imperial Clinical Phenotyping Centre, Department of 12 Surgery and Cancer, IRDB Building, Du Cane Road, Imperial College London, 13 London, W12 0NN, United Kingdom 14 4. Great North Children’s Hospital, Paediatric Immunology, Infectious Diseases & 15 Allergy, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon 16 Tyne, United Kingdom. 17 5. Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United 18 Kingdom 19 6. NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre based at Newcastle upon Tyne 20 Hospitals NHS Trust and Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United 21 Kingdom 22 7. Department of Paediatric Emergency Medicine, St Mary’s Hospital, Imperial College 23 NHS Healthcare Trust, London, United Kingdom 24 8. -

Overzicht Alle Beschreven Panden Deventer

Beschrijving van panden Naam Straat Huisnr Info Burgerweeshuis Tiel Achterweg 11 Het Burgerweeshuis dateert van 1905. Het werd gebouwd ter vervanging van het oude weeshuis aan het Hoogeinde. Het aantal weeskinderen, dat toentertijd in het nieuwe gebouw werd opgenomen, liep door de jaren heen gestaag terug. De eerste jaren waren het er gemiddeld zestig. Later nog maar enkele tientallen. Het gebouw heeft veel luiken, die dicht gingen als de kinderen naar bed gingen. Als instelling bestaat het Burgerweeshuis nog steeds, maar dan alleen nog om een fonds te beheren. Achter het gebouw bevond zich vroeger de stadsmuur. Ambtmanshuis Ambtmanstraat Het Ambtmanshuis is in 1525 oorspronkelijk gebouwd als woonhuis voor de ambtman, dijkgraaf en richter van de Neder-Betuwe, Adriaen van Bueren, getrouwd met Anna van Gelre, een onechte dochter van de militante Karel van Gelre. Een latere richter, Frederik Louis baron van Brakel, werd hier in 1761 vermoord door zijn schoonzoon Isaac Steven, baron van Deelen. Het gebouw kwam later in bezit van rijke families, zoals de Reuchlins, die er een kantoor van de Nederlandse Maatschappij voor Brandverzekering vestigden. In 1939 werd het de zetel van het polderdistrict Tielerwaard. De actrice Mary Dresselhuys verbleef in haar jeugd vaak in het Ambtmanshuis, waar haar moeder is geboren. In de hal hangt een portret van de actrice, geschilderd door Adé Peters. Het gebouw is nu eigendom van de gemeente Tiel en behoort vanaf 1996 tot het stadhuiscomplex. Stadhuis Tiel Ambtmanstraat 13 Kantoorpand, gebouwd in 1901, als onderkomen van de Tiel Brandverzekeringsmaatschappij. In 1937, toen de maatschappij verhuisde, is het pand overgedragen aan de gemeente en is sindsdien in gebruik als stadhuis. -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

Die Vereinsmitglieder Im Jahr 2017 Diverse

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Jahrbuch des Bochumer Botanischen Vereins Jahr/Year: 2018 Band/Volume: 9 Autor(en)/Author(s): diverse Artikel/Article: Die Vereinsmitglieder im Jahr 2017 7-8 © Bochumer Botanischer Verein e.V. Jahrb. Bochumer Bot. Ver. 9 7–8 2018 Die Vereinsmitglieder im Jahr 2017 Personen mit * haben einen Steckbrief auf der Vereinshomepage www.botanik-bochum.de Günter Abels (Geldern) Dr. Hans Jürgen Geyer, Dipl.-Chem. Helge Adamczak, Dipl.-Geogr. (Oberhausen) (Lippstadt) Sabine Adler (Bochum) Roland Gleich (Bochum) Klaus Adolphy, Dipl.-Biol. (Erkrath) Prof. Dr. Henning Haeupler* (Bochum) Helga Albert (Bochum) (Ehrenmitglied) Holger Bäcker, Dipl.-Biol. (Bochum) Martin Hank, B. Sc. Geogr. (Schwerte) Christian Beckmann, Dipl.-Landsch.-Ökol., Erika Heckmann (Dortmund) B. Sc. Geoinf. (Herten) Dr. Stefanie Heinze, M. Sc. Geogr. (Bochum) Stephanie Bednarz, B. Sc. Geogr. (Bochum) Monika Hertel (Straelen) Dr. H. Wilfried Bennert (Ennepetal) Dr. Ingo Hetzel*, Dipl.-Geogr. Dr. Michael Berger (Leverkusen) (Recklinghausen) (Vorstandsmitglied) Carolin Bohn, Dipl.-Biol. (Bochum) Jan Mattis Hetzel (Recklinghausen) Guido Bohn (Hamm) Jasmin Hetzel (Recklinghausen) Dr. F. Wolfgang Bomble*, Dipl.-Math. Mona Hetzel (Recklinghausen) (Aachen) (Mitglied der Schriftleitung) Paul Hitzke (Wamel/Möhnesee) Corinne Buch*, Dipl.-Biol. (Mülheim/Ruhr) Annette Höggemeier (Bochum) (Vorstandsmitglied, 1. Vorsitzende, René Hohmann, B. Sc. Geogr. Mitglied der Schriftleitung) (Fröndenberg) Rüdiger Bunk, Dipl.-Geogr. (Bochum) Caroline Homm, B. Sc. Geogr. (Bochum) Dietrich Büscher* (Dortmund) Wilhelm Itjeshorst, Dipl.-Biol. (Wesel) Benjamin Busse, Dipl.-Biol. (Dortmund) Dr. Katharina Jaedicke (Bochum) Susanne Cremer (Bochum) Dr. Armin Jagel*, Dipl.-Biol. (Bochum) Carola De Marco (Haltern am See) (Vorstandsmitglied, Schriftführer, Mitglied Bernhard Demel, Dipl.-Umweltwiss. -

The Age and Origin of the Gelderse Ijssel

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw | 87 – 4 | 323 - 337 | 2008 The age and origin of the Gelderse IJssel B. Makaske1,*, G.J. Maas1 & D.G. van Smeerdijk2 1 Alterra, Wageningen University and Research Centre, P.O. Box 47, 6700 AA Wageningen, the Netherlands. 2 BIAX Consult, Hogendijk 134, 1506 AL Zaandam, the Netherlands. * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: February 2008; accepted: September 2008 Abstract The Gelderse IJssel is the third major distributary of the Rhine in the Netherlands and diverts on average ~15% of the Rhine discharge northward. Historic trading cities are located on the Gelderse IJssel and flourished in the late Middle Ages. Little is known about this river in the early Middle Ages and before, and there is considerable debate on the age and origin of the Gelderse IJssel as a Rhine distributary. A small river draining the surrounding Pleistocene uplands must have been present in the IJssel valley during most of the Holocene, but very diverse opinions exist as to when this local river became connected to the Rhine system (and thereby to a vast hinterland), and whether this was human induced or a natural process. We collected new AMS radiocarbon evidence on the timing of beginning overbank sedimentation along the lower reach of the Gelderse IJssel. Our data indicate onset of overbank sedimentation at about 950 AD in this reach. We attribute this environmental change to the establishment of a connection between the precursor of the IJssel and the Rhine system by avulsion. Analysis of previous conventional radiocarbon dates from the upper IJssel floodplain yields that this avulsion may have started ~600 AD. -

Spoorkaart Van Nederland

Station / kaartvak / tabel Station / kaartvak / tabel Station / kaartvak / tabel A BCD Schiermonnikoog EF Hannover Aalten F4 70 Hardenberg F3 64 Sauwerd E1 84 Hamburg Abcoude C4 20, 31* Harderwijk D4 51 Schagen C2 20 Bremen Ameland Uithuizen UithuizermeedenRoodeschool Aerdenhout (Heemstede-) B4 10 Hardinxveld-Giessendam C5 19 Scheemda F1 85 Spoorkaart van Nederland Oldenburg Akkrum D2 51 Haren E1 51 Schiedam Nieuwland B5 18 83 Leer Usquert est Weener Alkmaar B3 13, 20 Harlingen D1 81 Schiedam Centrum B5 11, 18 Terschelling Alkmaar Noord C3 13, 20 Harlingen Haven D1 81 Schinnen E7 25 Almelo F3 41, 65*, 72 Heemskerk B3 13 Schin op Geul E7 26 Warffum 520 Stedum LoppersumAppingedamDelfzijl W Delfzijl Almelo de Riet F3 65 Heemstede-Aerdenhout B4 10 Schiphol C4 10, 21*, 30*, 40* Hoe gebruikt u de kaart ? 84 Almere Buiten D3 30, 32* Heerenveen D2 51 Seghwaert (Zoetermeer) B4 16 Baflo Bedum d Almere Centrum D3 30, 32* Heerhugowaard C3 13, 20 Sevenum (Horst-) E6 27 Almere Muziekwijk D4 30, 32* Heerlen E7 25, 26 Sint Gerlach (Houthem-) E7 26 Winsum 1 Bepaal langs welke kleur lijn of lijnen u reist. Almere Oostvaarders D3 30, 32* Heeze D6 25 Sittard E7 25 1 Sauwerd 1 Almere Parkwijk D3 30, 32* Buitenpost Heiloo B3 13, 20 Sliedrecht C5 19 Vlieland oningen Noor Alphen aan den Rijn C4 14, 15 Heino E3 65 Sneek D2 82 2 Indien uw reis één lijn betreft: Gr Zwaagwesteinde Nieuweschans Amersfoort D4 40, 41, 42, 51 Helder (Den) B2 20 Sneek Noord D2 82 80 Groningen oek kies een tabelnummer langs deze lijn.