Sir Robert Price Lecture, 1992 the Trouble with Synthesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Historical Group

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 64 Summer 2013 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Prof A T Dronsfield | Prof J Betteridge (Twickenham, 4, Harpole Close, Swanwick, Derbyshire, | Middlesex) DE55 1EW | Dr N G Coley (Open University) [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr C J Cooksey (Watford, Secretary: Prof. J. W. Nicholson | Hertfordshire) School of Sport, Health and Applied Science, | Prof E Homburg (University of St Mary's University College, Waldegrave | Maastricht) Road, Twickenham, Middlesex, TW1 4SX | Prof F James (Royal Institution) [e-mail: [email protected]] | Dr D Leaback (Biolink Technology) Membership Prof W P Griffith | Dr P J T Morris (Science Museum) Secretary: Department of Chemistry, Imperial College, | Mr P N Reed (Steensbridge, South Kensington, London, SW7 2AZ | Herefordshire) [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr V Quirke (Oxford Brookes Treasurer: Dr J A Hudson | University) Graythwaite, Loweswater, Cockermouth, | Prof. H. Rzepa (Imperial College) Cumbria, CA13 0SU | Dr. A Sella (University College) [e-mail [email protected]] Newsletter Dr A Simmons Editor Epsom Lodge, La Grande Route de St Jean, St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL [e-mail [email protected]] Newsletter Dr G P Moss Production: School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail [email protected]] http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/membership/networking/interestgroups/historical/index.asp 1 RSC Historical Group Newsletter No. 64 Summer 2013 Contents From the Editor 2 Obituaries 3 Professor Colin Russell (1928-2013) Peter J.T. -

View Responses of Scouts, Scout Leaders, and Scientists Who Were Scouts

ABSTRACT This study of science education in the Boy Scouts of America focused on males with Boy Scout experience. The mixed-methods study topics included: merit badge standards compared with National Science Education Standards, Scout responses to open-ended survey questions, the learning styles of Scouts, a quantitative assessment of science content knowledge acquisition using the Geology merit badge, and a qualitative analysis of interview responses of Scouts, Scout leaders, and scientists who were Scouts. The merit badge requirements of the 121 current merit badges were mapped onto the National Science Education Standards: 103 badges (85.12%) had at least one requirement meeting the National Science Education Standards. In 2007, Scouts earned 1,628,500 merit badges with at least one science requirement, including 72,279 Environmental Science merit badges. ―Camping‖ was the ―favorite thing about Scouts‖ for 54.4% of the boys who completed the survey. When combined with other outdoor activities, what 72.5% of the boys liked best about Boy Scouts involved outdoor activity. The learning styles of Scouts tend to include tactile and/or visual elements. Scouts were more global and integrated than analytical in their thinking patterns; they also had a significant intake element in their learning style. ii Earning a Geology merit badge at any location resulted in a significant gain of content knowledge; the combined treatment groups for all location types had a 9.13% gain in content knowledge. The amount of content knowledge acquired through the merit badge program varied with location; boys earning the Geology merit badge at summer camp or working as a troop with a merit badge counselor tended to acquire more geology content knowledge than boys earning the merit badge at a one-day event. -

Robert Burns Woodward

The Life and Achievements of Robert Burns Woodward Long Literature Seminar July 13, 2009 Erika A. Crane “The structure known, but not yet accessible by synthesis, is to the chemist what the unclimbed mountain, the uncharted sea, the untilled field, the unreached planet, are to other men. The achievement of the objective in itself cannot but thrill all chemists, who even before they know the details of the journey can apprehend from their own experience the joys and elations, the disappointments and false hopes, the obstacles overcome, the frustrations subdued, which they experienced who traversed a road to the goal. The unique challenge which chemical synthesis provides for the creative imagination and the skilled hand ensures that it will endure as long as men write books, paint pictures, and fashion things which are beautiful, or practical, or both.” “Art and Science in the Synthesis of Organic Compounds: Retrospect and Prospect,” in Pointers and Pathways in Research (Bombay:CIBA of India, 1963). Robert Burns Woodward • Graduated from MIT with his Ph.D. in chemistry at the age of 20 Woodward taught by example and captivated • A tenured professor at Harvard by the age of 29 the young... “Woodward largely taught principles and values. He showed us by • Published 196 papers before his death at age example and precept that if anything is worth 62 doing, it should be done intelligently, intensely • Received 24 honorary degrees and passionately.” • Received 26 medals & awards including the -Daniel Kemp National Medal of Science in 1964, the Nobel Prize in 1965, and he was one of the first recipients of the Arthur C. -

THE NINETY-THIRD PRESENTATION of the WILLARD GIBBS MEDAL (Founded by William A

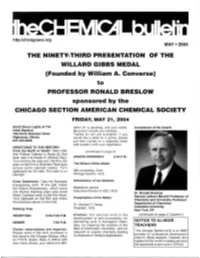

http:/chicagoacs.org MAY• 2004 THE NINETY-THIRD PRESENTATION OF THE WILLARD GIBBS MEDAL (Founded by William A. Converse) to PROFESSOR RONALD BRESLOW sponsored by the CHICAGO SECTION AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY FRIDAY, MAY 21, 2004 North Shore Lights at The iation for a nametag , and your check. Acceptance of the Award Hotel Moraine Be sure to include your address. 700 North Sheridan Road Tables fo r ten are availab le. If you Highwood, Illinois would like a table for a group, please 847-433-6366 put the ir names on a separate sheet and include it with your registration. DIRECTIONS TO THE MEETING From the North or South: Take 1-294 (continued on page 2) (the TriState Tollway) to Route 22. Exit east, take it to Route 41 (Skokie Hwy). AWARD CEREMONY 8:30 P.M. Turn north to the next exit, Old Elm. Go east on Old Elm to Sheridan Road Oust The Willard Gibbs Medal across some railroad tracks) . Turn right/south for 3/4 mile. The hotel is on Milt Levenberg, Chair the right. Chicago Section, ACS From Downtown: Take the Kennedy Introduction of the Medalist Expressway north. At the split , follow the Edens Expressway , which turns Madeleine Jacobs Executive Director & CEO, ACS into Skokie Highway past Lake Cook Dr. Ronald Breslow Road. Continue north to Old Elm Road. Presentation of the Medal Samuel Latham Mitchill Professor of Turn right/east on Old Elm and follow Chemistry and University Professor the directions above to the hotel. Dr. Charles P. Casey Department of Chemistry President, ACS Columbia University Parking: Free New York, NY RECEPTION 6:00-7:00 P.M. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Robert Michael Williams, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Robert Michael Williams, Ph.D. University Distinguished Professor of Chemistry Department of Chemistry, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Phone (970) 491-6747; FAX (970)-491-3944 e-mail: [email protected] Webpage: http://rwindigo1.chm.colostate.edu/ Personal Information: Date of birth: February 8, 1953 Married: Jill Janssen Williams Children: Ridge Janssen Williams (born February 23, 2001) Rainier Valentine Williams (born August 20, 2005) Education: B.A., Chemistry (with highest distinction), May, 1975. Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY. Thesis under Professor Ei-ichi Negishi on "A Stereoselective Synthesis of Partially Substituted 1,2,3-Butatriene Derivatives via Hydroboration". Ph.D., Organic Chemistry, June, 1979. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. Thesis advisor, Dr. W. H. Rastetter. Thesis title: "Epidithiapiperazinedione Syntheses". Postdoctoral Fellow, September 1979-September 1980, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. The late Professor R. B. Woodward group (Y. Kishi, principal investigator). Total synthesis of erythromycin A. Honors and Awards: Organic Synthesis Award, Local Rocky Mountain ACS Section, Reaching New Heights (2012) JSPS Invitation Fellowship Program for Research in Japan (Long-Term) 2012-2013 Ernest Guenther Award in the Chemistry of Natural Products, American Chemical Society (2011) Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation Senior Award (2009-2011) University Distinguished Professor, Colorado State University (2002) Arthur C. Cope Scholar Award, American -

Robert Burns Woodward 1917–1979

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ROBERT BURNS WOODWARD 1917–1979 A Biographical Memoir by ELKAN BLOUT Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs, VOLUME 80 PUBLISHED 2001 BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. ROBERT BURNS WOODWARD April 10, 1917–July 8, 1979 BY ELKAN BLOUT OBERT BURNS WOODWARD was the preeminent organic chemist Rof the twentieth century. This opinion is shared by his colleagues, students, and by other distinguished chemists. Bob Woodward was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and was an only child. His father died when Bob was less than two years old, and his mother had to work hard to support her son. His early education was in the Quincy, Massachusetts, public schools. During this period he was allowed to skip three years, thus enabling him to finish grammar and high schools in nine years. In 1933 at the age of 16, Bob Woodward enrolled in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to study chemistry, although he also had interests at that time in mathematics, literature, and architecture. His unusual talents were soon apparent to the MIT faculty, and his needs for individual study and intensive effort were met and encouraged. Bob did not disappoint his MIT teachers. He received his B.S. degree in 1936 and completed his doctorate in the spring of 1937, at which time he was only 20 years of age. Immediately following his graduation Bob taught summer school at the University of Illinois, but then returned to Harvard’s Department of Chemistry to start a productive period with an assistantship under Professor E. -

THE 101ST PRESENTATION of the WILLARD GIBBS MEDAL (Founded by William A

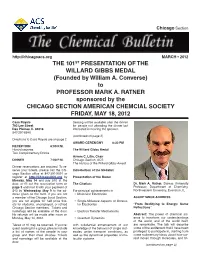

Chicago Section http://chicagoacs.org MARCH • 2012 THE 101ST PRESENTATION OF THE WILLARD GIBBS MEDAL (Founded by William A. Converse) to PROFESSOR MARK A. RATNER sponsored by the CHICAGO SECTION AMERICAN CHEMCIAL SOCIETY FRIDAY, MAY 18, 2012 Casa Royale Seating will be available after the dinner 783 Lee Street for people not attending the dinner but Des Plaines, IL 60016 interested in hearing the speaker. 847-297-6640 (continued on page 2) Directions to Casa Royale are on page 2. AWARD CEREMONY 8:30 PM RECEPTION 6:00 P.M. Hors-d’oeuvres The Willard Gibbs Medal Two Complimentary Drinks Avrom C. Litin, Chair DINNER 7:00 P.M. Chicago Section, ACS The History of the Willard Gibbs Award Dinner reservations are required. To re- serve your tickets, please call the Chi- Introduction of the Medalist cago Section office at 847-391-9091 or register at http://ChicagoACS.org by Presentation of the Medal Monday, May 14 and pay $40 at the door, or fill out the reservation form on The Citation: Dr. Mark A. Ratner, Dumas University page 5 and mail it with your payment of Professor, Department of Chemistry, $40 by Wednesday, May 9 to the ad- For principal achievements in Northwestern University, Evanston, IL dress given on the form. If you are not • Molecular Electronics a member of the Chicago Local Section, ACCEPTANCE ADDRESS you are not eligible for half price tick- • Single-Molecule Aspects of Molecu- ets for students, unemployed, or retired lar Electronics “From Rectifying to Energy: Some Chicago Section members. Tickets and Reflections” nametags will be available at the door. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Howard Schachman UC Berkeley Professor of Molecular Biology: On the Loyalty Oath Controversy, the Free Speech Movement, and Freedom in Scientific Research Interviews conducted by Ann Lage in 2000-2001 Copyright © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Howard Schachman, dated April 26, 2007. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Biographical Memoirs

National Academy of Sciences - Biographical Memoirs http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/online-collection.html By Michael P. Filosa Flack Norris (1871-1940) for the November Nucleus, I came across his biographical memoir on the website of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS). This memoir was written by John D. Roberts and was presented to the Academy in 1974, a scant(!) 34 years after his death. The NAS was founded in 1863 by 50 of the most prominent scientists in the United States, and its initial charter was signed by Abraham Lincoln. It is a tradition that each of its members be memorialized in a memoir to the Academy written by a peer (or two). These memoirs are a treasure trove of the history of science. The sole weakness is that they are posthumous and not necessarily, very timely. However, they are quite thorough and a good overview of the scientists, complete with a detailed listing of their major works. During my school years, I was always intrigued with stories about great scientists. Dan Kemp would talk extensively about his thesis advisor, R. B. Woodward, and his works. Those stories about Woodward (1917-1979) and also Gilbert Stork were very influential in my decision to pursue synthetic organic chemistry as a career. Woodward’s memoir was written by Elkan Blout (with assistance from Frank Westheimer) and was published in 2001, a “scant” 22 years after his death. The memoirs are often glowing: “Robert Burns Woodward was the preeminent organic chemist of the twentieth century. This opinion is shared by his colleagues, students and by other distinguished chemists.” Blout includes lengthy commentaries from Sir Derek Barton, Roald Hoffman and Albert Eschenmoser in the memoir. -

The World Around Is Physics

The world around is physics Life in science is hard What we see is engineering Chemistry is harder There is no money in chemistry Future is uncertain There is no need of chemistry Therefore, it is not my option I don’t have to learn chemistry Chemistry is life Chemistry is chemicals Chemistry is memorizing things Chemistry is smell Chemistry is this and that- not sure Chemistry is fumes Chemistry is boring Chemistry is pollution Chemistry does not excite Chemistry is poison Chemistry is a finished subject Chemistry is dirty Chemistry - stands on the legacy of giants Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794) Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867- 1934) John Dalton (1766- 1844) Sir Humphrey Davy (1778 – 1829) Michael Faraday (1791 – 1867) Chemistry – our legacy Mendeleev's Periodic Table Modern Periodic Table Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (1834-1907) Joseph John Thomson (1856 –1940) Great experimentalists Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858 –1937) Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (1888-1970) Chemistry and chemical bond Gilbert Newton Lewis (1875 –1946) Harold Clayton Urey (1893- 1981) Glenn Theodore Seaborg (1912- 1999) Linus Carl Pauling (1901– 1994) Master craftsmen Robert Burns Woodward (1917 – 1979) Chemistry and the world Fritz Haber (1868 – 1934) Machines in science R. E. Smalley Great teachers Graduate students : Other students : 1. Werner Heisenberg 1. Herbert Kroemer 2. Wolfgang Pauli 2. Linus Pauling 3. Peter Debye 3. Walter Heitler 4. Paul Sophus Epstein 4. Walter Romberg 5. Hans Bethe 6. Ernst Guillemin 7. Karl Bechert 8. Paul Peter Ewald 9. Herbert Fröhlich 10. Erwin Fues 11. Helmut Hönl 12. Ludwig Hopf 13. Walther Kossel 14. -

In Defense of the Use of the French Language in Scientific

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 39, Number 1 (2014) 73 IN DEFENSE OF THE USE OF THE FRENCH LANGUAGE IN SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION, 1965-1985: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL DELIBERATIONS AND AN INGENIOUSLY CLEVER TAKEOFF ON THE THEME BY R. B. WOODWARD Joseph Gal, Departments of Medicine and Pathology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO 80045, [email protected] and Jeffrey I. Seeman, Department of Chemistry, University of Richmond, Richmond, VA 23173, jseeman@ richmond.edu Supplemental Material Abstract Introduction For many decades, French scientists, the French The international nature of chemistry—indeed, of Académie des Sciences, and the government of France science—is a truism. Operationally, however, the practice have been concerned about the declining use of French of doing and communicating chemistry is not equally within the scientific milieu and the trend toward English and symmetrically shared throughout the world. That is as the universally-accepted language to communicate also a truism. The evidence that English has become the science. This trend is discussed with a focus on the issues unofficial language throughout the world in chemistry most vigorously debated in the time period 1965-1985, is multifold. For example, English is the only accepted including the reduced use of French in international sci- language of Pure and Applied Chemistry, the official entific communication resulting from the dominance of journal of the International Union of Pure and Applied English. A summary of the merging of national-chemical- Chemistry (IUPAC). Indeed, there has been a gradual society journals into international journals is also present- disappearance of non-English chemistry journals over ed.