A Case Study of the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library Rare Books Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Trails--Book Collecting for Fun, Not Profit Thomas W

Against the Grain Volume 28 | Issue 5 Article 27 2016 Oregon Trails--Book Collecting for Fun, Not Profit Thomas W. Leonhardt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Leonhardt, Thomas W. (2016) "Oregon Trails--Book Collecting for Fun, Not Profit," Against the Grain: Vol. 28: Iss. 5, Article 27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7524 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. ginning with modern cataloging standards (e.g., AACR, MARC format, Book Reviews FRBR, and RDA), the authors go on to focus on underlying principles, from page 50 which are rooted in the need to achieve maximum efficiencies. The limitations of these standards and of others developed specifically to describe digital information objects, such as Encoded Archival Descrip- Alemu, Getaneh and Brett Stevens. An Emergent Theory of tion (EAD), Dublin Core, and Metadata Object Description Schema Digital Library Metadata: Enrich then Filter. Chandos Informa- (MODS) are discussed in detail, and while acknowledging the benefits tion Professional Series. Kidlington, UK: Chandos Publishing, of standards-based, expert-created metadata, the authors contend that it 2015. 9780081003855. 122 pages. $78.95. fails to adequately represent the diversity of views and perspectives of potential users. Additionally, the imperative to “enrich” expert-created Reviewed by Mary Jo Zeter (Latin American and Caribbean metadata with metadata created by users is not only a practical response Studies Bibliographer, Michigan State University Libraries) to the rapidly increasing amount of digital information, argue the au- thors, it is necessary in order to fully optimize the potential of Linked <[email protected]> Data. -

The Index to the Library Chronicle: Subject Index

10/21/2020 The Index to the Library Chronicle: Subject Index Libraries Home | Mobile | My Account | Renew Items | Sitemap | Help The Index to the Library Chronicle: Subject Index A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Introduction Author Index Italicized page numbers refer to photographs and illustrations. A ^-top-^ "A" (Zukofsky), N.S. nos.38/39 (1987):77-105 A.D. Peters Agency. See Peters (A.D.) Agency A Tutti I Fedeli D'Amore (Alighieri), v.23, nos.2/3 (1993):132 Abbeychurch (Yonge), v.23, no.1 (1993):17-19 Abbott, Claude Colleer, Further Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins, N.S. nos.46/47 (1989):69 ABC of Reading (Pound), v.20, nos.1/2 (1990):14-16, 17 Abernethy, Milton A. Contempo editorship, N.S. no.27 (1984):20-44; v.25, no.3 (1995):111-31, 119-20 photograph of, v.20, no.4 (1991):83 Pound's Draft of XXX Cantos and, v.25, no.3 (1995):126, 127-31 Abril, Manuel, line-drawing, N.S. no.13 (1980):23 Across the River and Into the Trees (Hemingway), N.S. no.30 (1985):16-28 Act Without Words (Beckett), N.S. no.28 (1984):97-104, 103, 115 Acton, Harold, N.S. no.1 (1970):25 Actors. See individual actors Actresses. See individual actresses L'Adamo, sacra rapresentazione (Andreini), v.23, nos.2/3 (1993):126 Adams, Ansel, N.S. no.19 (1982):118, N.S. no.19 (1982):121 Adams, Maude, N.S. -

Bismya; Or the Lost City of Adab : a Story of Adventure, of Exploration

The Lost City of Adab 1 ' i %|,| / ";'M^"|('1j*)'| | Edgar James Banks l (Stanttll Wttfrmttg |fitag BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcm-ij W. Sage 1891 fjjRmf... Lifoi/jL 3777 Cornell University Library DS 70.S.B5B21 Bismya: or The lost city of Adab 3 1924 028 551 913 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028551913 The Author as an Arab. Bismya or The Lost City of Adab A Story of Adventure, of Exploration, and of Excavation among the Ruins of the Oldest of the Buried Cities of Babylonia By Edgar James Banks, Ph.D. Field Director of the Expedition of the Oriental Exploration Fund of the University of Chicago to Babylonia With 174 Illustrations G. P. Putnam's Sons New York and London Gbe IRnfcfeerbocfter press 1912 t.v. Copyright, 1912 BY EDGAR JAMES BANKS Ube TKniefeerbocftei: ipresg, mew ffiorft The University of Chicago office of the president Chicago, June 12, 1912. On the recommendation of the Director of the Baby- lonian Section of the Oriental Exploration Fund of the University of Chicago, permission has been granted to Dr. Edgar J. Banks, Field Director of the Fund at Bismya, to publish this account of his work in Mesopotamia. Dr. Banks was granted full authority in the field. He is entitled therefore to the credit for successes therein, as of course he will receive whatever criticism scholars may see fit to make. -

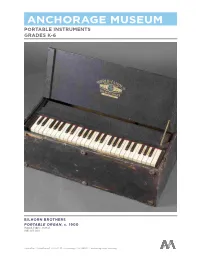

Anchorage Museum Portable Instruments Grades K-6

ANCHORAGE MUSEUM PORTABLE INSTRUMENTS GRADES K-6 BILHORN BROTHERS PORTABLE ORGAN, c. 1900 Wood, fabric, metal 1981.012.001 Education Department • 625 C St. Anchorage, AK 99501 • anchoragemuseum.org ACTIVITY AT A GLANCE Learn about portable instruments. Look closely at a portable reed organ from the late 1800s/early 1900s. Learn more about the organ and its owner. Listen to a video of a similar organ being played and learn more about how the instrument works. Brainstorm and sketch a portable instrument. Investigate other portable instruments in the Anchorage Museum collection. Create an instrument from recycled materials. PORTABLE ORGAN Begin by looking closely at the portable organ made by the Bilhorn Brothers company. If investigating the portable organ with another person, use the questions below to guide your discussions. If working alone, consider recording thoughts on paper: CLOSE-LOOKING Look closely, quietly at the organ for a few minutes. OBSERVE Share your observations about the organ or record your initial thoughts ASK • What do I notice about the organ? • What colors and materials does the artist use? • What sounds might the organ create? • What does it remind you of? • What more do you see? • What more can you find? DISCUSS USE 20 Questions Deck for more group discussion questions about the organ. LEARN MORE ABOUT THE MANUFACTURER Peter Philip Bilhorn was a well-known evangelist singer and composer who invented a portable reed organ to support his musical endeavors. With the support of his brother, George Bilhorn, he founded Bilhorn Brothers Organ Company of Chicago in 1885. Bilhorn Brothers manufactured portable reed organs, including the World-Famous Folding Organ in the Anchorage Museum collection. -

July / August 2015

saith: I will bring the blind by a way that they knew not; I will lead a St. Gregory’s Journal them in paths that they have not known; I will make darkness light before them, and crooked things straight; these things will I do a July/August, 2015 - Volume XX, Issue 7 unto them and not forsake them.[Is. 42:16] rom the Apostle John we learn how this was fulfilled: We know St. Gregory the Great Orthodox Church that the Son of God is come, and hath given us an 1443 Euclid Street, NW, Washington, DC - stgregoryoc.org F understanding, that we may know him that is true, and we are in A Western Rite Congregation of the Antiochian Archdiocese him that is true, even in his Son. [1 John 5:20] We love him, because he first loved us. God, by loving us, reneweth his image in us. And that he may find in us the likeness of his goodness, he giveth us grace to do his works. To this end he lighteth the soul as From a Homily of early beloved, if we study diligently the though it were a candle. And so it is that he doth enkindle in our Saint Leo the Great Dhistory of the hearts the fire of his holy charity, in order that we may love both died AD 461 creation of our race, we him and whatsoever he loveth. Feast Day ~ April 11 shall find that man was made in the image of God, to the end that he might St. -

Resource Utilization in Unalaska, Aleutian Islands, Alaska

RESOURCE UTILIZATION IN UNALASKA, ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, ALASKA Douglas W. Veltre, Ph. D. Mary J. Veltre, B.A. Technical Paper Number 58 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence October 23, 1982 Contract 824790 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report would not have been possible to produce without the generous support the authors received from many residents of Unalaska. Numerous individuals graciously shared their time and knowledge, and the Ounalashka Corporation,. in particular, deserves special thanks for assistance with housing and transportation. Thanks go too to Linda Ellanna, Deputy Director of the Division of Subsistence, who provided continuing support throughout this project, and to those individuals who offered valuable comments on an earlier draft of this report. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. ii Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Purpose ..................... 1 Research objectives ............... 4 Research methods 6 Discussion of rese~r~h'm~tho~oio~y' ........ ...... 8 Organization of the report ........... 10 2 BACKGROUNDON ALEUT RESOURCE UTILIZATION . 11 Introduction ............... 11 Aleut distribuiiin' ............... 11 Precontact resource is: ba;tgr;ls' . 12 The early postcontact period .......... 19 Conclusions ................... 19 3 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND. 23 Introduction ........................... 23 The precontact'plrioi . 23 The Russian period ............... 25 The American period ............... 30 Unalaska community profile. ........... 37 Conclusions ................... 38 4 THE NATURAL SETTING ............... -

Russian–American Telegraph from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from Western Union Telegraph Expedition)

Russian–American telegraph From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Western Union Telegraph Expedition) The Russian American telegraph , also known as the Western Union Telegraph Expedition and the Collins Overland telegraph , was a $3,000,000 undertaking by the Western Union Telegraph Company in 1865-1867, to lay an electric telegraph line from San Francisco, California to Moscow, Russia. The route was intended to travel from California via Oregon, Washington Territory, the Colony of British Columbia and Russian Alaska, under the Bering Sea and across Siberia to Moscow, where lines would communicate with the rest of Europe. It was proposed as an alternate to long, deep underwater cables in the Atlantic. Abandoned in 1867, the Russian American Telegraph was considered an economic failure, but history now deems it a "successful failure" because of the many benefits the exploration brought to the regions that were traversed. Contents ■ 1 Perry Collins and Cyrus West Field ■ 2 Preparations ■ 3 Route through Russian Alaska ■ 4 Route through British Columbia ■ 5 Legacy ■ 6 Places named for the expedition members ■ 7 Books and memoirs written about the expedition ■ 8 Further reading ■ 9 External links ■ 10 Notes Perry Collins and Cyrus West Field By 1861 the Western Union Telegraph Company had linked the eastern United States by electric telegraph all the way to San Francisco. The challenge then remained to connect North America with the rest of the world. [1] Working to meet that challenge was Cyrus West Field's Atlantic Telegraph Company, who in 1858 had laid the first undersea cable across the Atlantic Ocean. However, the cable had broken three weeks afterwards and additional attempts had thus far been unsuccessful. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Fairbanks Field Hearing Chairman Lisa Murkowski March 28, 2016

Opening Statement: Fairbanks Field Hearing Chairman Lisa Murkowski March 28, 2016 Good afternoon, everyone, and Happy Seward’s Day. I am delighted to call this Field Hearing to order in our Golden Heart city of Fairbanks. I want to start by thanking the Pipeline Training Center for hosting us. And I want to welcome our witnesses and all who have joined us for this important discussion about resource development in Alaska. As many of you likely know, it was gold mining that ultimately determined the location of Fairbanks. Captain Barnette’s riverboat ran out of draft on the Chena, and fate determined where his mining supply business was to be located. And while Barnette was too late and too far away to profit from the Klondike gold rush, he helped create the Fairbanks gold rush. Today, Fort Knox and Pogo, world-class gold mines north and south of the city, continue the proud tradition that give meaning to Fairbanks’ motto. This region – like so much of our state – is blessed with vast natural resources that we can use to gain prosperity and fulfill the promises of our statehood. Today is Seward’s Day, we can laugh about Seward’s Ice Box or Seward’s Folly, but not even Seward could conceive of the resource wealth the U.S. purchased from Russia. Alaska has what virtually no one else has: tens of billions of barrels of oil, hundreds of trillions of cubic feet of natural gas, a massive supply of coal, and countless deposits of hardrock minerals. Of course renewable resources beyond imagination. -

Iditarod National Historic Trail I Historic Overview — Robert King

Iditarod National Historic Trail i Historic Overview — Robert King Introduction: Today’s Iditarod Trail, a symbol of frontier travel and once an important artery of Alaska’s winter commerce, served a string of mining camps, trading posts, and other settlements founded between 1880 and 1920, during Alaska’s Gold Rush Era. Alaska’s gold rushes were an extension of the American mining frontier that dates from colonial America and moved west to California with the gold discovery there in 1848. In each new territory, gold strikes had caused a surge in population, the establishment of a territorial government, and the development of a transportation system linking the goldfields with the rest of the nation. Alaska, too, followed through these same general stages. With the increase in gold production particularly in the later 1890s and early 1900s, the non-Native population boomed from 430 people in 1880 to some 36,400 in 1910. In 1912, President Taft signed the act creating the Territory of Alaska. At that time, the region’s 1 Iditarod National Historic Trail: Historic Overview transportation systems included a mixture of steamship and steamboat lines, railroads, wagon roads, and various cross-country trail including ones designed principally for winter time dogsled travel. Of the latter, the longest ran from Seward to Nome, and came to be called the Iditarod Trail. The Iditarod Trail today: The Iditarod trail, first commonly referred to as the Seward to Nome trail, was developed starting in 1908 in response to gold rush era needs. While marked off by an official government survey, in many places it followed preexisting Native trails of the Tanaina and Ingalik Indians in the Interior of Alaska. -

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

Refashioning Production in Bristol Bay, Alaska by Karen E. Hébert A

Wild Dreams: Refashioning Production in Bristol Bay, Alaska by Karen E. Hébert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Fernando Coronil, Chair Associate Professor Arun Agrawal Associate Professor Stuart A. Kirsch Associate Professor Barbra A. Meek © Karen E. Hébert 2008 Acknowledgments At a cocktail party after an academic conference not long ago, I found myself in conversation with another anthropologist who had attended my paper presentation earlier that day. He told me that he had been fascinated to learn that something as “mundane” as salmon could be linked to so many important sociocultural processes. Mundane? My head spun with confusion as I tried to reciprocate chatty pleasantries. How could anyone conceive of salmon as “mundane”? I was so confused by the mere suggestion that any chance of probing his comment further passed me by. As I drifted away from the conversation, it occurred to me that a great many people probably deem salmon as mundane as any other food product, even if they may consider Alaskan salmon fishing a bit more exotic. At that moment, I realized that I was the one who carried with me a particularly pronounced sense of salmon’s significance—one that I shared with, and no doubt learned from, the people with whom I conducted research. The cocktail-party exchange made clear to me how much I had thoroughly adopted some of the very assumptions I had set out simply to study. It also made me smile, because it revealed how successful those I got to know during my fieldwork had been in transforming me from an observer into something more of a participant.