Evaluation of Protected Areas – a Case Study of Chitwan National Park of Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne Mclean Charles Sturt University (Australia)

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 19 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin; Special Article 8 Topic: The Tharu 1999 Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation McLean, Joanne (1999) "Conservation and the Impact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal," HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 19 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol19/iss2/8 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conservation and the linpact of Relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal Joanne McLean Charles Sturt University (Australia) Since the establishment of the first national park in the United States in the nineteenth century, indig enous peoples have been forced to move from regions designated as parks. Some of these people have been relocated to other areas by the government, more often they have been told to leave the area and are given no alternatives (Clay, 1985:2). Introduction (Guneratne 1994; Skar 1999). The Thant are often de scribed as one people. However, many subgroups exist: The relocation of indigenous people from national Kochjla Tharu in the eastern Tarai, Chitwaniya and Desauri parks has become standard practice in developing coun in the central Tarai, and Kathariya, Dangaura and Rana tries with little regard for the impacts it imposes on a Tharu in the western Tarai (Meyer & Deuel, 1999). -

2 Chitwan District: Asset Baseline

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 44168-012 Capacity Development Technical Assistance (CDTA) October 2013 Nepal: Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development (Financed by the Strategic Climate Fund) District Baseline Reports: Department of Water Supply and Sewerage (DWSS) – Urban Watsan Chitwan, Dolakha, and Kathmandu Districts Prepared by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. MOSTE | Mainstreaming climate change risk management in development | WATSAN-Urban district baselines TA – 7984 NEP October, 2013 Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development 1 Main Consultancy Package (44768-012) CHITWAN DISTRICT BASELINE: DEPARTMENT OF WATER SUPPLY AND SEWERAGE (DWSS) – URBAN WATSAN Prepared by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management METCON Consultants APTEC Consulting Prepared for Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment, Government of Nepal Environment Natural Resources and Agriculture Department, South Asia Department, Asian Development Bank Version B i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 CHITWAN DISTRICT .......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Chitwan Sector Master Plan ........................................................................................... -

CHITWAN-ANNAPURNA LANDSCAPE: a RAPID ASSESSMENT Published in August 2013 by WWF Nepal

Hariyo Ban Program CHITWAN-ANNAPURNA LANDSCAPE: A RAPID ASSESSMENT Published in August 2013 by WWF Nepal Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. Citation: WWF Nepal 2013. Chitwan Annapurna Landscape (CHAL): A Rapid Assessment, Nepal, August 2013 Cover photo: © Neyret & Benastar / WWF-Canon Gerald S. Cubitt / WWF-Canon Simon de TREY-WHITE / WWF-UK James W. Thorsell / WWF-Canon Michel Gunther / WWF-Canon WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program / Pallavi Dhakal Disclaimer This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Kathmandu Forestry College (KAFCOL) and do not necessarily reflect the views of WWF, USAID or the United States Government. © WWF Nepal. All rights reserved. WWF Nepal, PO Box: 7660 Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal T: +977 1 4434820, F: +977 1 4438458 [email protected] www.wwfnepal.org/hariyobanprogram Hariyo Ban Program CHITWAN-ANNAPURNA LANDSCAPE: A RAPID ASSESSMENT Foreword With its diverse topographical, geographical and climatic variation, Nepal is rich in biodiversity and ecosystem services. It boasts a large diversity of flora and fauna at genetic, species and ecosystem levels. Nepal has several critical sites and wetlands including the fragile Churia ecosystem. These critical sites and biodiversity are subjected to various anthropogenic and climatic threats. Several bilateral partners and donors are working in partnership with the Government of Nepal to conserve Nepal’s rich natural heritage. USAID funded Hariyo Ban Program, implemented by a consortium of four partners with WWF Nepal leading alongside CARE Nepal, FECOFUN and NTNC, is working towards reducing the adverse impacts of climate change, threats to biodiversity and improving livelihoods of the people in Nepal. -

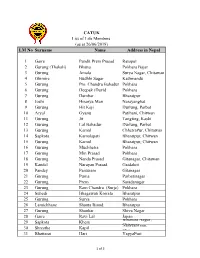

LATEST and FINAL 26-06-19.Xlsx

CATUK List of Life Members (as at 26/06/2019) LM No Surname Name Address in Nepal 1 Gaire Pandit Prem Prasad Ratopul 2 Gurung (Thakali) Bhanu Pokhara Bajar 3 Gurung Amala Surya Nagar, Chitawan 4 Ghimire Budhhi Sagar Kathmandu 5 Gurung Pro. Chandra Bahadur Pokhara 6 Gurung Deepak (David Pokhara 7 Gurung Dambar Bharatpur 8 Joshi Hiranya Man Narayanghat 9 Gurung Hit Kaji Durlung, Parbat 10 Aryal Gyanu Patihani, Chitwan 11 Gurung Jit Tangting, Kaski 12 Gurung Lal Bahadur Durlung, Parbat 13 Gurung Kamal ChhetraPur, Chitawan 14 Sapkota Kamalapati Bharatpur, Chitwan 15 Gurung Kamal Bharatpur, Chitwan 16 Gurung Muchhetra Pokhara 17 Gurung Min Prasad Pokhara 18 Gurung Nanda Prasad Gitanagar, Chitawan 19 Kandel Narayan Prasad Gaidakot 20 Pandey Parsuram Gitanagar 21 Gurung Purna Parbatinagar 22 Gurung Prem Saradanagar 23 Gurung Ram Chandra (Surje) Pokhara 24 Subedi Bhagawati Koirala Bharatpur 25 Gurung Surya Pokhara 26 Lamichhane Shanta Binod Bharatpur 27 Gurung Shankar Shiva Nagar 28 Gaire Ravi Lal Japan Birendra Nagar , 29 Sapkota Khem NarayanGhat,Chitawan 30 Shrestha Kapil Chitawan 31 Bhattarai Hari YagyaPuri 1 of 5 32 Poudel Kamal Bharatpur 33 Gurung Lok Gunja Nagar 34 Ghale Shiva Kumar Surya Nagar 35 Gurung Himal Bharatpur 36 Sharma Subas Subas Sharma 37 Gurung Hima Rampur 38 Shreshtha Basanta Rampur 39 Subedi Tank Kawasati 40 Adhikari Prakash Bharatpur 41 Dhakal Shankar Bharatpur 42 Shreshtha Devendra Gita Nagar 43 Gurung Krishna Bharatpur 44 Gurung Abhisek Rampur 45 Sapkota Bhim Rampur 46 Shreshtha Madan Kumar Gita Nagar 47 Gurung Krishna -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

Chitwan National Park Laid the Foundation Stone

Rural Landscape Change: Landscape Practices, Values and Meanings The Case of Jagatpur VDC, Chitwan Nepal By By Dal Prasad Pun Master of Philosophy in Social Change Department of Geography Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Trondheim, Norway May, 2004 Rural Landscape Change: Landscape Practices, Values and Meanings The Case of Jagatpur VDC, Chitwan Nepal By Dal Prasad Pun Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Master of Philosophy in Social Change Department of Geography Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Trondheim, Norway May, 2004 Abstract In Nepal the nature conservation practices started during 1970s and the establishment of the Royal Chitwan National Park laid the foundation stone. Though the nature conservation practices in Nepal have undergone changes to date, from purely protective to participatory conservation at the landscape level, the rural people around the conservation areas in general have faced complicated problems due to the restriction on the use of natural resources and the encroachment and threat of wild animals on their agricultural fields, human lives and domestic animals. In this context the present study explores rural landscape change in Jagatpur VDC after the implementation of the Royal Chitwan National Park. The main focus of this study was to look at how the rural landscape practices and the landscape values and meanings have changed over time and space, changing the rural landscape. The subjects were the traditional people and the migrants who were purposively selected using snowball sampling. Data triangulation i.e. structured open ended interviews, informal conversational interviews, observation and photography, were applied to collect the qualitative information. -

Annual-Report Final

NEPAL PUBLIC HEALTH FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT 2015 – 16 ADVISORS Mr. Kul Chandra Gautam Dr. Rita Thapa Prof. Dr. Mathura P.Shrestha Dr. Suniti Acharya Kenneth J. Rothman (Boston) NPHF EXECUTIVE BOARD PRESIDENT Dr. Mahesh Kumar Maskey VICE PRESIDENT Dr. Badri Raj Pande GENERAL SECRETARY Prof. Dr. Sharad Onta TREASURER Dr. Tirtha Rana MEMBERS Dr. Bharat Pradhan, Dr. Binjwala Shrestha, Dr. Chhatra Amatya, Ms. Daya Laxmi Joshi, Dr. Kedar P Baral, Mr. Shant lal Mulmi, Prof. Dr. Shiba K. Rai, Dr. Shrikrishna Giri FOUNDING MEMBERS Dr. Aarati Shah, Dr. Achala Baidhya , Ms. Alina Maharjan, Dr. Arjun Karki, Dr. Aruna Upreti, Mr. Ashok Bhurtyal, Dr. Bhagwan Koirala, Dr. B D Chataut, Dr. Buddha Basnyat, Prof. D. S Manandhar, Dr. Gajananda P. Bhandari, Mr. I. M. Shrestha, Dr. Karuna Onta, Dr. Lonim Prasai Dixit, Dr. Nabin Shrestha , Dr. Narendra Shrestha, Dr. Nilambar Jha, Dr. Rajani Shah, Dr. Rajendra BC, Dr. Ramesh Kant Adhikari, Dr. Renu Rajbhandari, Dr. Sameer Mani Dixit, Dr. Shyam Thapa, Dr. Suresh Mehata LIFE MEMBERS Dr. Abhinav Vaidya, Dr. Archana Amatya, Mr. Bishnu Choulagai, Dr. Lochana Shrestha, Mr. Narayan Subedi LEGAL ADVISOR Mr. Badri Pathak (Listed alphabetically by first name) MESSAGE FROM EXECUTIVE CHAIR It is my great privilege to pen the foreword of the Annual Report 2015/16 of Nepal Public Health Foundation after resumption of my of responsibility as the executive chair. I would like to take this opportunity to thank the executive board, office bearers especially acting chair and vice-president Dr. Badri Raj Pande, and the dedicated staffs for their untiring efforts in sustaining and helping NPHF to gain new heights. -

Database of Members Till 202

M No Business Name Address Proprietor Name mobile 6566 Chitwan Beauty Parlour Unity Bharatpur M.C., 3, Belchowk Mina Upreti 9855050970 6565 New Saraswoti Sun Chadi Pasal Bharatpur M.C., 1, Putalibazr Chhabilal B.K. 9845110575 6564 Galaxy Empire Lounge and Bar Pvt. Ltd. Bharatpur M.C., 1, Bhrikuti Path Vishal Shrestha 9841587514 6563 Life Care Sanitary & Napkin Udhyog & Suppliers Pvt. Ltd. Bharatpur M.C., 7, Bishal Chock Lok Nath Lamichhane 9855063439 6562 Earning Export Import Pvt. Ltd. Bharatpur M.C., 7, Bishal Chock Hemanta Bajgain 9841737903 6561 Sankalpa International Surjicare Bharatpur M.C., 3, Bishal Marga Chandra Shingh Bhandari 9845023698 6560 Aanya Traders Bharatpur M.C., 1, Main Road Shashi Droliya 9801073251 6559 Nihon Education Centre pvt. Ltd. Bharatpur M.C., 3, Lions Chock Shambhu Panta 9845790162 6558 Jems Medicine Distributors Bharatpur M.C., 6, cancer get Dil Kumari Tiwari 9845026336 6557 Kamal Medical Hall Bharatpur M.C., 1, shahidchowk Bikram Basnet 9863377142 6556 Big Food Industry Bharatpur M.C., 11, Nayakiran Chitra Kumari Gurung 9845248557 6555 Ojasjkara Builders Pvt. Ltd. Bharatpur M.C., 12, Malpot Chowk Suraj Sedhai 9855065373 6554 Intelligent Job Link & Training Center Pvt. Ltd Bharatpur M.C., 10, chitwan Dinesh Bahadur Darji 056523768 6553 Chitwan Poly Pipe Industries Bharatpur M.C., 4, Ramghat Ram Prasad Gajurel 9855057150 6552 Riman & Aayan Traders Bharatpur M.C., 1, Chitwan Rajesh Shrestha 9840073151 6551 Jay maa Laxmi Stores Bharatpur M.C., 1, Milan Road Akhilesh Kumar 9809259337 6550 New Mani Enterprises Bharatpur M.C., 1, Junhalroad Pankaj Kumar Gupta 9845882773 6549 Kasturi Trade House Bharatpur M.C., 1, Pragatipath Nischal Ghimire 9811215607 6548 A. -

Sujan Pandit TOURISM DEVELOPMENT and ITS IMPACT on the LIVELIHOOD of the THARUS a Case Study of Chitwan National Park, Nepal

Sujan Pandit TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND ITS IMPACT ON THE LIVELIHOOD OF THE THARUS A Case Study of Chitwan National Park, Nepal Thesis CENTRAL OSTROBOTHNIA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Degree Programme in Tourism January 2012 ABSTRACT CENTRAL OSTROBOTHNIA Date Author UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED January 2012 Sujan Pandit SCIENCE Degree programme Degree programme in tourism Name of thesis TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND ITS IMPACT ON THE LIVELIHOOD OF THE THARUS A Case Study of Chitwan National Park, Nepal Instructor Pages Keshar Bahadur Pandit 53 Supervisor Katarina Broman The Nepal government has used a bio-diversity conservation strategy and tourism development in an around the conservation area of the Chitwan National Park. This study was conducted in Sauraha, buffer zone area of Chitwan National Park where the Tharus, an indigenous and ethnic people of Terai, has been living for a long time as original dwellers and a malaria resistant people. The objective of the study was to explore social and economic impacts of tourism on the Tharus livelihood and situation of tourism in the Chitwan National Park (Sauraha). This study is based on both qualitative and quantitative secondary data and the analysis of secondary data taken from different kinds of sources. In addition, observation method was applied in the field work in Sauraha. The study revealed that the establishments of the national park and the tourism development have transformed the area into a touristic place. Further, the livelihood of the Tharus has been affected by the establishment of the national park since their livelihood traditionally depended on the resources of the park. The tourism development and establishment of the park forced them to diversify the Tharus livelihood in order to cope with the situation. -

Name Account Number Address NETRA PRASAD NEPAL

Name Account Number Address NETRA PRASAD NEPAL 0010000411012 DHUWAKOT-03, DHADING RADHIKA ADHIKARI 0010000412012 NILKANTHA-02, DHADING KRISHNA SHARAN RIMAL 0010000414812 KALYANPUR-1,NUWAKOT SABITRI DABADI 0010000420612 JAUBARI-7, GORKHA DEEPAK POUDEL 0010000428212 TERATHUM PRAMOD SAPKOTA 0010000429012 KHUDUNABARI-2, JHAPA GHANSHYAM MANANDHAR 0010000438512 KHNIYA PANI-5, RAMECHHAP, RAJESH SHAHI 0010000081612 KATHMANDU-13 PRAKASH SHARMA GYAWALI 0010000084512 BAGAHA-8,RUPENDEHI BODH RAJ POUDEL 0010000089012 DHAKURPOKHARI,KASKI PRIYANKA PARAJULI 0010000106812 MORANG-1 RAM CHANDRA PANDEY 0010000112112 PALUMTAR-8 ARJUN MAHARJAN 0010000121612 TUTEPANI-14 MANOHAR MAN SHRESTHA 0010000122012 H.N 827, DEVKOTA SADAK R. RAMAN/SAMIR/DHIRAJ 0010000125212 NAMJUNG-6 DEVKI KUMARI THAPA 0010000129112 CHAINPUR VDC TEK BDR. KHATRI 0010000138512 PATALEY RATNA BDR. POUDEL 0010000141512 MADHUMALLA VDC-3 SUMAN POKHAREL 0010000141812 KUPANDOLE, LALITPUR SHOVA PANT TRIPATHI 0010000144112 MALIGAUN-4 DHRUBA SHARMA ACHARYA 0010000148312 SAUDIYAR-6 ARJUN PANDEY 0010000149612 ASHRANG-9 SANGEET SHRESTHA 0010000153012 HETAUDA-4, MAKWANPUR PURNA/PRADEEP/PRATIVA 0010000157812 MASEL-2 SATYENDRA RAJ SUBEDI 0010000318312 BHIMASTHAN 2 AKANSHYA SHAH 0010000319412 THAPATHALI KUSHUM RAI 0010000321308 MAHARAJGUNJ,TUSHAL-4 RAM LACHHI 0010000352312 THE CHANDBAGH SCHOOL BHARAT ARYAL / ARJUN B. K 0010000356712 KHAHARE-07, KAVRE BISHNU LAMSAL 0010000367412 WALLING-7, SYANGJA MANITA ADHIKARI 0010000371612 BHARTE-1, DEURALI, LAMJUNG RAM CHANDRA RIMAL 0010000374912 KHADGABHANJANG-5, NUWAKOT TRAVELS DE' KATHMANDU 0010000382801 NAGPOKHARI-01, KATHMANDU MANISHA LAXMI SHRESTHA 0010000383012 RAVIBHAWAN-13, KATHMANDU RANGA NATH POUDEL 0010000383612 KULESHOWER, KATHMANDU DAMBAR BAHADUR KARKI 0010000389812 SUKEDHARA-4,KTM GOPI LAMA 0010000397612 XAVIER COLLEGE UDDHAV THAPA 0010000006212 CHAPALI-8, KATHMANDU BIMARSHA KHANAL 0010000026112 KHASYAULI-4,PALPA LAXMI PRASAD PATHAK 0010000031212 MORANG-1 RAM PRASAD LAMSAL 0010000033612 GULERIYA-8,BARDIYA BENI BAHADUR DANGI 0010000034412 RAMPUR,KANCHANPUR,BILASIPUR-3 TULSHI BDR. -

Final Voter's List.Xlsx

CHITWAN AID TRUST UK VOTER LIST 2021-2023 S.N. NAME ADDRESS REMARKS 1 Gaire Pandit Prem Prasad Ratopul 2 Gurung (Thakali) Bhanu Pokhara Bajar 3 Gurung Amala Surya Nagar, Chitawan 4 Ghimire Budhhi Sagar Kathmandu 5 Gurung Pro. Chandra Bahadur Pokhara 6 Gurung Deepak (David ) Pokhara 7 Gurung Dambar Bharatpur 8 Joshi Hiranya Man Narayanghat 9 Gurung Hit Kaji Durlung, Parbat 10 Aryal Gyanu Patihani, Chitwan 11 Gurung Jit Tangting, Kaski 12 Gurung Lal Bahadur Durlung, Parbat 13 Kamal ChhetraPur ChhetraPur, Chitawan 14 Sapkota Kamalapati Bharatpur, Chitwan 15 Gurung Kamal Bharatpur, Chitwan 16 Gurung Muchhetra Pokhara 17 Gurung Min Prasad Pokhara 18 Gurung Nanda Prasad Gitanagar, Chitawan 19 Kandel Narayan Prasad Gaidakot 20 Pandey Parsuram Gitanagar 21 Gurung Purna Parbatinagar 22 Gurung Prem Saradanagar 23 Gurung Ram Chandra (Surje) Pokhara 24 Subedi Bhagawati Koirala Bharatpur 25 Gurung Surya Pokhara 26 Lamichhane Shanta Binod Bharatpur 27 Gurung Shankar Shiva Nagar 28 Gaire Ravi Lal Japan 29 Sapkota Khem Birendra Nagar , 30 Shrestha Kapil NarayanGhat, 31 Bhattarai Hari YagyaPuri 32 Poudel Kamal Bharatpur 33 Gurung Lok Gunja Nagar 34 Ghale Shiva Kumar Surya Nagar 35 Gurung Himal Bharatpur 36 Sharma Subas Subas Sharma 37 Gurung Hima Rampur 38 Shreshtha Basanta Rampur 39 Subedi Tank Kawasati 40 Adhikari Prakash Bharatpur 41 Dhakal Shankar haratpur 42 Shreshtha Devendra Gita Nagar 43 Gurung Krishna Bharatpur 44 Gurung Abhisek Rampur 45 Sapkota Bhim Rampur 46 Shreshtha Madan Kumar Gita Nagar 47 Gurung Krishna BDR Chhetrapur 48 Gurung Ram Sarada -

Socio-Cultural Impact in Tourism: a Case Study of Sauraha, Nepal

ISSN: 2362-1303 (Paper) | eISSN: 2362-1311(Online) JOURNAL OF ADVANCED ACADEMIC RESEARCH (JAAR) July 2014 Socio-Cultural Impact in Tourism: A Case Study of Sauraha, Nepal Janardan Poudel1 1Ph.D Scholar, Mewar University Gangrar, Chittorgar, Rajasthan, India ABSTRACT Locaton: Sauraha is 166 km. south west from Kathmandu. It is situated at an altitude of 150m (492 feet) form the sea level. Its shape is rectangular and speared with east west direction. It is in close proximity with the Chitwan National Park, Tandi and Chitrasari being at a distance of 6 and 3 km. respectively from it. However, Tandi, the entry point to Sauraha, is situated on the east west highway, 20km. from the main city of Bharatpur. Objective: The objective of the study is to study the socio cultural impact in Tharus’ culture, customs, tradition and lifestyle by tourism. Methodology: Observation and questionnaire method will be used as data collection tools. This research will adopt descriptive research design. Descriptive in a sense: the research will carefully try to record all the observed events from the study area and describes fairly as possible. Result: Local people have changed their life style, their traditional values, cultural aspects and are following the borrowed values and aspects in the name of modernization. Conclusion: Sauraha, is the best location for the tourism industry. It is a part of Bachhauly VDC. It is worldwidely famous for its ethnic and cultural diversity. Numbers of tourists have come to visit the Chitwan National Park and most of the tourists go to Sauraha to stay and to study the cultural and traditional aspects of the Tharus.