'Lenin's Jewish Question'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Annual Report

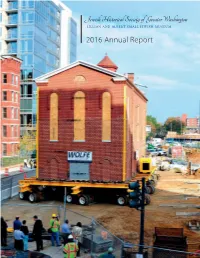

2016 Annual Report 209455_Annual Report.indd 1 8/4/17 9:56 AM Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington LILLIAN AND ALBERT SMALL JEWISH MUSEUM 2016 Major Achievements The Society . • Held our last program in the Lillian & Albert Small Jewish Museum on the 140th anniversary of the historic 1876 synagogue. • Moved the synagogue 50 feet into the intersection of Third & G – the first step on its journey to a new home and the Society’s new Museum. • Received national coverage of the historic synagogue move from The Washington Post, The New York Times, Associated Press, and other news outlets. By the Numbers . • 17 youth programs served 451 students. • 3,275 adults participated in 81 programs at 30 venues. • 19 donors contributed more than 100 photographs, 30 boxes of archival documents, and 14 objects to the archives. • 70 historians, students, media outlets, organizations, and genealogists around the globe received answers to their research requests. • 34,094 website visits from 148 countries, 3,263 YouTube video views, and 1,281 Facebook fans. • 31 volunteers contributed more than 350 hours. The publication of this Annual Report was made possible, in part, with support from the Rosalie Fonoroff Endowment Fund. 209455_Annual Report.indd 2 8/4/17 9:56 AM 1 Leadership Message THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT OF OUR WORK IN 2016! hakespeare wrote that “What’s past is prologue,” describing Finally, we bid farewell to longtime Executive Director, Laura elegantly how history sets the context for the present. Apelbaum, who resigned after 22 years of committed service. SThe same maxim describes the point at which the Jewish During her tenure, the Society expanded its activities on every Historical Society of Greater Washington finds itself in 2017: level, gained a reputation for excellent programming and sound moving forward to design, finance and ultimately build a administration, and laid the groundwork for the successful wonderful new museum, archive, and venue for education, completion of the new museum. -

Lenin-S-Jewish-Question

Lenin’s Jewish Question Lenin’s Jewish Question YOHANAN PETROVSKY-SHTERN New Haven and London Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College. Copyright © 2010 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Set in Minion type by Integrated Publishing Solutions. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petrovskii-Shtern, Iokhanan. Lenin’s Jewish question / Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-15210-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Relations with Jews. 2. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Family. 3. Ul’ianov family. 4. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Public opinion. 5. Jews— Identity—Case studies. 6. Jewish question. 7.Jews—Soviet Union—Social conditions. 8. Jewish communists—Soviet Union—History. 9. Soviet Union—Politics and government. I. Title. DK254.L46P44 2010 947.084'1092—dc22 2010003985 This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Lenin a Revolutionary Life

lenin ‘An excellent biography, which captures the real Lenin – part intel- lectual professor, part ruthless and dogmatic politician.’ Geoffrey Swain, University of the West of England ‘A fascinating book about a gigantic historical figure. Christopher Read is an accomplished scholar and superb writer who has pro- duced a first-rate study that is courageous, original in its insights, and deeply humane.’ Daniel Orlovsky, Southern Methodist University Vladimir Il’ich Ulyanov, known as Lenin was an enigmatic leader, a resolute and audacious politician who had an immense impact on twentieth-century world history. Lenin’s life and career have been at the centre of much ideological debate for many decades. The post-Soviet era has seen a revived interest and re-evaluation of the Russian Revolution and Lenin’s legacy. This new biography gives a fresh and original account of Lenin’s personal life and political career. Christopher Read draws on a broad range of primary and secondary sources, including material made available in the glasnost and post-Soviet eras. Focal points of this study are Lenin’s revolutionary ascetic personality; how he exploited culture, education and propaganda; his relationship to Marxism; his changing class analysis of Russia; and his ‘populist’ instincts. This biography is an excellent and reliable introduction to one of the key figures of the Russian Revolution and post-Tsarist Russia. Christopher Read is Professor of Modern European History at the University of Warwick. He is author of From Tsar to Soviets: The Russian People and Their Revolution, 1917–21 (1996), Culture and Power in Revolutionary Russia (1990) and The Making and Breaking of the Soviet System (2001). -

Institute for the Study of Modern Israel ~ISMI~

Institute for the Study of Modern Israel ~ISMI~ November 10 – 11, 2018 Atlanta, Georgia ISMI.EMORY.EDU 1 2 Welcome to the 20th Anniversary Celebration of the Emory Institute for the Study of Modern Israel (ISMI). SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2018 1:30pm-1:45pm Opening Remarks (Ken Stein) 1:45pm-2:45pm Israel: 1948-2018 A Look Back to the Future (Asher Susser, Yitzhak Reiter, Yaron Ayalon, Rachel Fish, Ken Stein-moderator) 2:45pm-3:00pm Break 3:00pm-4:15pm Israel and its Neighborhood (Alan Makovsky, Jonathan Schanzer, Joel Singer, Asher Susser-moderator) 4:15pm-5:30pm US Foreign Policy toward Israel (Todd Stein, Alan Makovsky, Jonathan Schanzer, Ken Stein-moderator) 5:30pm-6:00pm Break 6:00pm-6:45pm Wine Reception 6:45pm-7:45pm ISMI at Emory: Impact on Emory College, Atlanta and Beyond (Introductory Remarks by Ambassador Judith Varnai Shorer, Consul General of Israel to the Southeastern United States, Michael Elliott, Dov Wilker, Lois Frank, Joshua Newton, Jay Schaefer, Ken Stein-moderator) 7:45pm-8:45pm Dinner 9:00pm-10:00pm Musical Performance by Aveva Dese with Introduction by Eli Sperling 10:30pm-midnight AFTER HOURS Reading Sources and Shaping Narratives: 1978 Camp David Accords (Ken Stein) SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2018 7:00am-8:30am Breakfast 8:30am-9:30am Israel and the American Jewish Community (Allison Goodman, Jonathan Schanzer, Alan Makovsky, Ken Stein-moderator) 9:30am-10:30am Reflections of Israel Learning at Emory (Dana Pearl, Jay Schaefer, Mitchell Tanzman, Yaron Ayalon, Yitzhak Reiter, Ken Stein-moderator) 10:30am-10:45am Break 10:45am-11:30am Foundations, Donors, and Israel Studies (Stacey Popovsky, Rachel Fish, Dan Gordon, Ken Stein-moderator) 11:30am-12:30pm One-state, two states, something else? (Rachel Fish, Yitzhak Reiter, Joel Singer, Jonathan Schanzer, Ken Stein-moderator) 12:30pm-12:45pm Closing Remarks - ISMI’s Future and What’s Next 12:45pm Box Lunch 3 Full Agenda - Saturday November 10, Saturday – 1:30pm-1:45pm Opening Remarks Welcoming thoughts about our two days of learning. -

A GENEALOGICAL MIRACLE - Thanks to the Jewish Agency Arlene Blank Rich

cnrechw YCO" " g g-2 "& rgmmE CO +'ID pbP g " 6 p.ch 0"Y 3YW GS € cno I cl+. P. 3 k. $=& L-CDP 90a3-a Y3rbsP gE$$ (o OSN eo- ZQ 3 (Dm rp,7r:J+. 001 PPP wr.r~Rw eY o . 0"CD Co r+ " ,R Co CD w4a nC 1 -4 Q r up, COZ - YWP I ax Z Q- p, P. 3 3 CD m~ COFO 603" 2 %u"d~. CD 5 mcl3Q r. I= E-35 3s-r.~E Y e7ch g$g", eEGgCD CD rSr(o Coo CO CO3m-i-I V"YUN$ '=z CD Eureka was finding that her maiden name was MARK- at the age of 27 to GROSZ JULISKA, age 18. TOLEVOT: THE JOURNAL Of JEWISH GENEALOGY TOLEPOT is the Hebrew word for "genealogyw OVICS MARI. The last column of the register It is difficult to understand why two bro- or llgenerations. " showed that my great-uncle had petitioned to have thers should change their names and why one should 155 East 93 Street, Suite 3C TOLEDOT disclaims responsibility for errors his name changed to VAJDA SAMUEL, which my father choose VAJDA and the other SALGO. My cousin wrote New York, NY 10028 of fact or opinion made by contributors told me about in 1946 when I first became inter- that all she knew about our great-grandparents is but does strive for maximum accuracy. ested in my genealogy. that they were murdered in the town of Beretty6Gj- Arthur Kurzweil Steven W. Siege1 Interested persons are invited to submit arti- In the birth register for the year 1889, I falu. -

The Early Female Jewish Members of the Maryland Bar: 1920–1929

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ UM Law Maryland Law Review Volume 74 | Issue 3 Article 4 The aE rly Female Jewish Members of the Maryland Bar: 1920–1929 Deborah Sweet Eyler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Society Commons, Legal History, Theory and Process Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Women Commons Recommended Citation 74 Md. L. Rev. 545 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EARLY FEMALE JEWISH MEMBERS OF THE MARYLAND BAR: 1920–1929 ∗ THE HONORABLE DEBORAH SWEET EYLER Etta Haynie Maddox, the first female member of the Maryland Bar, was born into a family rooted for generations in Maryland.1 In the sixteen years following her 1902 bar admission, she was joined by six more wom- en, three of whom also came from long-established American families.2 The other three were daughters of at least one immigrant, but those parents had come to this country long before their daughters were born.3 All seven women admitted to the Maryland Bar from 1902 to 1918 were Gentiles.4 © 2015 Deborah Sweet Eyler. ∗ Hon. Deborah Sweet Eyler, Associate Judge, Maryland Court of Special Appeals. I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. -

LENIN the DICTATOR an Intimate Portrait

LENIN THE DICTATOR An Intimate Portrait VICTOR SEBESTYEN LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd v 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 © Victor Sebestyen 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher. The right of Victor Sebestyen to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. HB ISBN 978 1 47460044 6 TPB 978 1 47460045 3 Typeset by Input Data Services Ltd, Bridgwater, Somerset Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Weidenfeld & Nicolson The Orion Publishing Group Ltd Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ An Hachette UK Company www.orionbooks.co.uk LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd vvii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 In Memory of C. H. LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd vviiii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 MAPS LLeninenin TThehe DDictatorictator - PP4.indd4.indd xxii 117/01/20177/01/2017 112:372:37 NORTH NORWAY London SEA (independent 1905) F SWEDEN O Y H C D U N D A D L Stockholm AN IN GR F Tammerfors FRANCE GERMANGERMAN EMPIRE Helsingfors EMPIRE BALTIC Berlin SEA Potsdam Riga -

THE ANNALS of IOWA 73 (Spring 2014)

The Annals of Volume 73 Number 2 Iowa Spring 2014 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue SHARI RABIN, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at Yale University, uses correspondence from Jews in early Iowa to show how Iowa Jews used the Jewish press to create and disseminate authority, information, and community, in the process shaping local Jewish life and creating a national American Jewry. PATRICIA N. DAWSON, librarian/curator at the Hubbell Museum and Library in Des Moines, provides biographical information on three generations of the Cowles family, one of the most influential families in Iowa history, and describes the collection of materials about the family held by Cowles Library at Drake University. Front Cover John Cowles (center) enjoys the moment as Wendell Willkie greets an unidentified man, ca. 1940. For more on the Cowles family and the collection of materials on them held by the Cowles Library at Drake University, see Patricia N. Dawson’s article in this issue. Photo from the Archives at Cowles Library, Drake University. Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. David Edmunds, University of Texas University at Dallas Kathleen Neils Conzen, University of H. Roger Grant, Clemson University Chicago William C. Pratt, University of Nebraska William Cronon, University of Wisconsin– at Omaha Madison Glenda Riley, Ball State University Robert R. Dykstra, State University of Malcolm J. Rohrbough, University of Iowa New York at Albany Dorothy Schwieder, Iowa State University The Annals of Third Series, Vol. 73, No. 2 Spring 2014 Iowa Marvin Bergman, editor Contents 101 “A Nest to the Wandering Bird”: Iowa and the Creation of American Judaism, 1855–1877 Shari Rabin 128 Manuscript Collections: The Cowles Family Publishing Legacy in the Drake Heritage Collections Patricia N. -

Zlotnik Family – Berdichev (Also Boryslav and Lvov)

1 Summary of Information on Zlotnik and Waldman Families Also: Linhard-Blum- Silber-Rock-Nadler Families Notes: 1. This information is only on life in Poland-Ukraine-Lithuania in 19th and 20th Centuries, mainly up to 1930 – maybe 1945. 2.Rabbinical marriages were called “Ritual Marriages” by the Austrian/Polish/Russian authorities and were not legally recognized. Hence in many cases the children are registered under their mother’s maiden name and not their fathers. For that reason both family names have to be considered. This seems to have changed to fathers name only after approx. ………………….(1920?) 3. Berdichev-Boryslav at different times under Austrian/Polish/Russian control. Hence archives may be in Lvov, Warsaw, Kiev etc… Archives in Riga Lithuania are relevant for Lurie family. 4. See attached family tree. 5. Compiled and updated, 15th April 2014 by Phil Bloom. Still incomplete. Zlotnik family – Berdichev (also Boryslav and Lvov) 1. Judah (Yehuda, Yankelevich?) and Basche, parents of Jacob Ber Zlotnik, their surname might have been Zlotnik or other or no surname) Address: Berdichev, Rosja) (Judah ’s “register of death: sygnatura 1753”)1 perhaps born 1790 if they were 40 when Jacob born – and perhaps born 1810 if they were aged 20 when Jacob was born. 1 (possible – but needs to be checked further) * Juda Zlotnik died 1897 Boryslav (could Yitzhak have brought his parents Judah and Basche to Boryslav where they then lived and died?) * Juda leib Zlotnik born 1842 in Przasnysz, father Abram Feiwlowicz, mother Ruchla Feiwlowicz, *Bashe Zlotnik (Bashia? Batya?), died 1897 Boryslav – could be mother of Jacob Ber Zlotnik ? *Aron-Leizer Zlotnik - patronym Kalmanovich – age at least 25 in 1906 (could be a cousin- sibling?) same generation as Yitzhak Waldman.Kiev,region? Berdichev, record of trade tax and being on voters list for Duma. -

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition completion of this landmark project in December 2021. of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah rare or unique books have now been digitized and put photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article online for researchers, teachers, and students around the (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. world to read. The next important step in developing YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East European explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures Jewish Life. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, will launch in March 2020. For the first Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us time, original documents, books, and other artifacts will online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). be translated into English and set in a historical context for general audiences worldwide through this Museum. In 2019 we also initiated work on the 4th Shine Jonathan Brent Online Educational Series class on Jewish food. -

![[Inside] 910 Polk Boulevard U.S](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8776/inside-910-polk-boulevard-u-s-6098776.webp)

[Inside] 910 Polk Boulevard U.S

HESHVAN/KISLEV 5763 OCTOBER 02 THE GREATER DES MOINES Published as a CommunityJewishJewish Service by the Jewish Federation of Greater Des Moines online at Pressdmjfed.orgPress volume 19 number 2 Herb Eckhouse And Marilyn Hurwitz To Co-Chair Campaign The Federation is proud to announce the selection of Herb Eckhouse and Marilyn Hurwitz as Co-Chairs of the 2003 All-in-One Campaign. Marilyn and Herb will lead the drive to gain community support. This support enables the Federation to help the community live, learn and play togeth- er; embrace diversity and promote understanding; to perform acts of tze- dakah to those most needful amongst us, and to extend a welcoming hand. Jewish Press: Herb, some people may not know how important their support for the All-In-One actually is. Please explain the All-in-One Campaign for their benefit. Herb Eckhouse: We have been blessed through the years by the generosity of community members whose support has enabled us to build up a rich offering of A. H. Blank (r.) strikes a pose with Mae West. Photo courtesy of the Iowa Jewish Historical Society. Jewish services. Each year, we return to The IJHS says: the Jewish community and ask for sup- port to maintain and enhance our offer- “Why don’t you come up and see us sometime?” ings. Annual pledges keep the lights on and enable us to retain highly qualified A.H. Blank and Mae West. Just one of the many photographs, Iowa. He served as director of American Broadcasting staff. If you care about the quality of our scrapbooks and articles donated to the Iowa Jewish Historical Corporation – United Paramount Theaters, and president of community, you'll want to help! But it Society and Caspe Heritage Gallery by Myron Blank. -

\J'a~Kj ~~C -Wry in the 21St Century." ;;An Jewish Philanthropy," American ~ \It/V'y"" / F A..U.,; I - Z Ctucj

'1 \O O-r 7) J'?').. T /1')'ll£t '( ~ yv-.. ..- /~ Steven M. Cohen WrftY\ Q.,V\ I ~ ....j U-.Cl t1 ( 5 V\ \J'A~kj ~~C -wry in the 21st Century." ;;an Jewish Philanthropy," American ~ \It/V'Y"" / f a..u.,; I - Z ctUcJ. I,jv" I ew York: 1989). Women's Transformations of Public Judaism: and Other Prescriptions for Jewish r -alism"; Liebman and Cohen, "Jewish , Religiosity, Egalitarianism, and the Symbolic I I ! Jewish Families and Their Jewish Power of Changing Gender Roles -ents of Pre-schoolers: Their Jewish ~ \g~q~ =-- diss., Jewish Theological Seminary, "It - Sylvia Barack Fishman -nary and Mixed Marriages"; Phillips, ~ : 11 (BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY) For more than three decades, activists in the United States and Israel, as well as in some small diaspora Jewish communities, have worked toward making the Jewish re ligion more egalitarian, with the goal of enabling women to play central roles in pub lic Judaism. Although egalitarianism might seem inimical to the fundamental hierar chical nature of halakhic Judaism, the focus of Jewish feminists in the United States I (and, to a much lesser extent, in Israel and elsewhere) has been persistently religious ·1 1 .I since shortly after the beginnings of second wave feminism in the early 1960s. This I essay explores women's transformations of public Judaism, concentrating on com munal rituals and life-cycle ceremonies, synagogue life, and diverse educational set tings, which are arguably the loci most meaningful to westernized, religiously affili ated Jews. This essay begins with a consideration of the peculiarly religious nature of the I American ethos and the impact of that religiosity on American Judaism-especially ! on Jewish feminism in the United States.