Lenin-S-Jewish-Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Annual Report

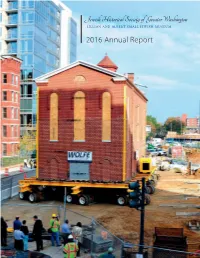

2016 Annual Report 209455_Annual Report.indd 1 8/4/17 9:56 AM Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington LILLIAN AND ALBERT SMALL JEWISH MUSEUM 2016 Major Achievements The Society . • Held our last program in the Lillian & Albert Small Jewish Museum on the 140th anniversary of the historic 1876 synagogue. • Moved the synagogue 50 feet into the intersection of Third & G – the first step on its journey to a new home and the Society’s new Museum. • Received national coverage of the historic synagogue move from The Washington Post, The New York Times, Associated Press, and other news outlets. By the Numbers . • 17 youth programs served 451 students. • 3,275 adults participated in 81 programs at 30 venues. • 19 donors contributed more than 100 photographs, 30 boxes of archival documents, and 14 objects to the archives. • 70 historians, students, media outlets, organizations, and genealogists around the globe received answers to their research requests. • 34,094 website visits from 148 countries, 3,263 YouTube video views, and 1,281 Facebook fans. • 31 volunteers contributed more than 350 hours. The publication of this Annual Report was made possible, in part, with support from the Rosalie Fonoroff Endowment Fund. 209455_Annual Report.indd 2 8/4/17 9:56 AM 1 Leadership Message THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT OF OUR WORK IN 2016! hakespeare wrote that “What’s past is prologue,” describing Finally, we bid farewell to longtime Executive Director, Laura elegantly how history sets the context for the present. Apelbaum, who resigned after 22 years of committed service. SThe same maxim describes the point at which the Jewish During her tenure, the Society expanded its activities on every Historical Society of Greater Washington finds itself in 2017: level, gained a reputation for excellent programming and sound moving forward to design, finance and ultimately build a administration, and laid the groundwork for the successful wonderful new museum, archive, and venue for education, completion of the new museum. -

'Socialism in One Country': Komsomol'tsy

Youthful Internationalism in the Age of ‘Socialism in One Country’: Komsomol’tsy, Pioneers and ‘World Revolution’ in the Interwar Period Matthias Neumann On the 1st of March 1927, two Komsomol members from the Chuvash Republic, located in the centre of European Russia, wrote an emotional letter to Comrade Stalin. Reflecting on the revolutionary upheavals in China, they attacked the inaction of the Komsomol and the party and expressed their sincere determination to self-mobilise and join the proletarian forces in China. ‘We do not need empty slogans such as “The Komsomol is prepared”’, ‘We must not live like this’ they wrote and boasted ‘we guarantee that we are able to mobilise thousands of Komsomol members who have the desire to go to China and fight in the army of the Guomindang.’ This was after all, they forcefully stressed, the purpose for which ‘our party and our Komsomol exist.’1 These youngsters were not alone in their views. As the coverage on the situation in China intensified in the Komsomol press in March, numerous similar individual and collective letters were received by party and Komsomol leaders.2 The young authors, all male as far as they were named, expressed their genuine enthusiasm for the revolution in China. The letters revealed not only a youthful romanticism for the revolutionary fight abroad and the idea of spreading the revolution, but often an underlying sense of disillusionment with the inertia of the revolutionary project at home. A few months earlier, in 1926 during the campaign against the so-called eseninshchina3, a fellow Komsomol member took a quite different view on the prospect of spreading the revolution around the world. -

Body Found Andrei Yustschinsky on 20 March (!) 1911 the Body of a Boy

Body found Andrei Yustschinsky On 20 March 096/04/Friday 10h32 Body found Andrei Yustschinsky On 20 March (!) 1911 the body of a boy was found on the border of the urban area of Kiev in a clay pit. It was found in a half-sitting position, the hands were tied together upon the back with a cord. The body was dressed merely with a shirt, underpants, and a single stocking. Behind the head, in a depression in the earthen wall, which according to the record of the then Kiev attorney and high school teacher Gregor Schwartz-Bostunitsch was inscribed with mystical signs, were found five rolled-together school exercise books which bore the name "property of the student of the fore-class, Andrei Yustschinsky, Sophia School"; because of this, the identification was made very shortly. It turned out to be the thirteen-year-old son of the middle-class woman Alexandra Prichodko of Kiev. The Kievskaya Mysl (Kiev Thought) gave the following report at the time about the discovery of the body: "When the body of the unfortunate boy was carried out of the pit, the crowd shuddered, and sobbing could be heard. The aspect of the slain victim was terrible. His face was dark blue and covered with blood, and a several windings of a strong cord, which cut into the skin, were wrapped around the arms. There were three wounds on the head, which all came from some kind of piercing tool. The same wounds were also on the face and on both sides of the neck. -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

The Anti-Imperial Choice This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Anti-Imperial Choice the Making of the Ukrainian Jew

the anti-imperial choice This page intentionally left blank The Anti-Imperial Choice The Making of the Ukrainian Jew Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern Yale University Press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Ehrhardt type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petrovskii-Shtern, Iokhanan. The anti-imperial choice : the making of the Ukrainian Jew / Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-13731-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Jewish literature—Ukraine— History and criticism. 2. Jews in literature. 3. Ukraine—In literature. 4. Jewish authors—Ukraine. 5. Jews— Ukraine—History— 19th century. 6. Ukraine—Ethnic relations. I. Title. PG2988.J4P48 2009 947.7Ј004924—dc22 2008035520 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). It contains 30 percent postconsumer waste (PCW) and is certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). 10987654321 To my wife, Oxana Hanna Petrovsky This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Politics of Names and Places: A Note on Transliteration xiii List of Abbreviations xv Introduction 1 chapter 1. -

Rus Sian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917– 1920

Rus sian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917– 1920 —-1 —0 —+1 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd i 8/19/11 8:37 PM JEWISH CULTURE AND CONTEXTS Published in association with the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies of the University of Pennsylvania David B. Ruderman, Series Editor Advisory Board Richard I. Cohen Moshe Idel Alan Mintz Deborah Dash Moore Ada Rapoport- Albert Michael D. Swartz A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher. -1— 0— +1— 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd ii 8/19/11 8:37 PM Rus sian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917– 1920 Oleg Budnitskii Translated by Timothy J. Portice university of pennsylvania press philadelphia —-1 —0 —+1 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd iii 8/19/11 8:37 PM Originally published as Rossiiskie evrei mezhdu krasnymi i belymi, 1917– 1920 (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2005) Publication of this volume was assisted by a grant from the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation. Copyright © 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104- 4112 www .upenn .edu/ pennpress Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 -1— Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data 0— ISBN 978- 0- 8122- 4364- 2 +1— 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd iv 8/19/11 8:37 PM In memory of my father, Vitaly Danilovich Budnitskii (1930– 1990) —-1 —0 —+1 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd v 8/19/11 8:37 PM -1— 0— +1— 137-48292_ch00_1P.indd vi 8/19/11 8:37 PM contents List of Abbreviations ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1. -

Military Despatches Vol 24, June 2019

Military Despatches Vol 24 June 2019 Operation Deadstick A mission vital to D-Day Remembering D-Day Marking the 75th anniversary of D-Day Forged in Battle The Katyusha MRLS, Stalin’s Organ Isoroku Yamamoto The architect of Pearl Harbour Thank your lucky stars Life in the North Korean military For the military enthusiast CONTENTS June 2019 Page 62 Click on any video below to view Page 14 How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and Thank your lucky stars techno-speak that few Serving in the North Korean Military outside the military could hope to under- 32 stand. Some of the terms Features were humorous, some Rank Structure 6 This month we look at the Ca- were clever, while others nadian Armed Forces. were downright crude. Top Ten Wartime Urban Legends Ten disturbing wartime urban 36 legends that turned out to be A matter of survival Part of Hipe’s “On the fiction. This month we’re looking at couch” series, this is an 10 constructing bird traps. interview with one of Special Forces - Canada 29 author Herman Charles Part Four of a series that takes Jimmy’s get together Quiz Bosman’s most famous a look at Special Forces units We attend the Signal’s Associ- characters, Oom Schalk around the world. ation luncheon and meet a 98 47 year old World War II veteran. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

Lenin a Revolutionary Life

lenin ‘An excellent biography, which captures the real Lenin – part intel- lectual professor, part ruthless and dogmatic politician.’ Geoffrey Swain, University of the West of England ‘A fascinating book about a gigantic historical figure. Christopher Read is an accomplished scholar and superb writer who has pro- duced a first-rate study that is courageous, original in its insights, and deeply humane.’ Daniel Orlovsky, Southern Methodist University Vladimir Il’ich Ulyanov, known as Lenin was an enigmatic leader, a resolute and audacious politician who had an immense impact on twentieth-century world history. Lenin’s life and career have been at the centre of much ideological debate for many decades. The post-Soviet era has seen a revived interest and re-evaluation of the Russian Revolution and Lenin’s legacy. This new biography gives a fresh and original account of Lenin’s personal life and political career. Christopher Read draws on a broad range of primary and secondary sources, including material made available in the glasnost and post-Soviet eras. Focal points of this study are Lenin’s revolutionary ascetic personality; how he exploited culture, education and propaganda; his relationship to Marxism; his changing class analysis of Russia; and his ‘populist’ instincts. This biography is an excellent and reliable introduction to one of the key figures of the Russian Revolution and post-Tsarist Russia. Christopher Read is Professor of Modern European History at the University of Warwick. He is author of From Tsar to Soviets: The Russian People and Their Revolution, 1917–21 (1996), Culture and Power in Revolutionary Russia (1990) and The Making and Breaking of the Soviet System (2001). -

Russian Novels in Marathi Polysystem 87

RUSSIAN NOVELS IN MARATHI POLYSYSTEM 87 Chapter IV: RUSSIAN NOVELS IN MARATHI POLYSYSTEM The Marathi polysystem created a subsystem of translated literature in the historical colonial context. It also created a space for Russian literature within the subsystem of translated literature as a result of the factors mentioned in the last chapter. This chapter attempts to analyse the trends of translation of some representative Russian texts in Marathi polysystem. We conduct this study with concrete literary works translated into Marathi and try to find out exactly which literary works have been entered into Marathi polysystem since 1932. We need to analyse the factors, which played a decisive role in the selection of these works by Marathi polysystem. It is important to determine the function of Russian literature (Novels, Short Stories and Dramas) in Marathi polysystem. This is what we attempt to touch in our next three chapters. II Russian Literature: A Brief Historical Sketch Before we analyse the translations of Russian literary works in the Marathi polysystem, it becomes essential for us to have a brief historical view of the Russian literature. An account of the development of Russian literary polysystem acquaints us with the process of its formation as well as the major events and literary creations in Russia. This shows us how vast the Russian polysystem is and what part of it has entered into Marathi polysystem through translations. Secondly, this also helps us to define the status of the literary texts (chosen for translation into Marathi) in Russian polysystem. Then eventually we can compare it with the status/role/function of the translated text in the Marathi polysystem. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2019

INSIDE: UWC leadership meets with Zelenskyy – page 3 Lomachenko adds WBC title to his collection – page 15 Ukrainian Independence Day celebrations – pages 16-17 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association, Inc., celebrating W its 125th anniversaryEEKLY Vol. LXXXVII No. 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2019 $2.00 Trump considers suspension of military aid Zelenskyy team takes charge to Ukraine, angering U.S. lawmakers as new Rada begins its work RFE/RL delay. Unless, of course, he’s yet again act- ing at the behest of his favorite Russian dic- U.S. President Donald Trump is consid- tator & good friend, Putin,” the Illinois sena- ering blocking $250 million in military aid tor tweeted. to Ukraine, Western media reported, rais- Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.), a member of ing objections from lawmakers of both U.S. the House Foreign Affairs Committee, tweet- political parties. ed that “This is unacceptable. It was wrong Citing senior administration officials, when [President Barack] Obama failed to Politico and Reuters reported that Mr. stand up to [Russian President Vladimir] Trump had ordered a reassessment of the Putin in Ukraine, and it’s wrong now.” aid program that Kyiv uses to battle Russia- The administration officials said chances backed separatists in eastern Ukraine. are that the money will be allocated as The review is to “ensure the money is usual but that the determination will not be being used in the best interest of the United made until the review is completed and Mr. States,” Politico said on August 28, and Trump makes a final decision.