Converts of Conviction Studies and Texts in Scepticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012 Initial terms: 24 or 72 kinds Torah/Talmud (oral/written law).Halacha orthopraxy/orthodoxy, haskalah Babylonian Talmud kabbalah, Sephardic, Ashkenazi (with material gleaned from Wikipedia articles- no access to my books yet) Modern Judaism is loosely broken into three main branches: Orthodox Judaism is the approach to Judaism which adheres to the traditional interpretation and application of the laws and ethics of the Torah as legislated in the Talmudic texts by the Sanhedrin ("Oral Torah") and subsequently developed and applied by the later authorities known as the Gaonim, Rishonim, and Acharonim. Orthodox Jews are also called "observant Jews"; Orthodoxy is known also as "Torah Judaism" or "traditional Judaism". Orthodox Judaism generally refers to Modern Orthodox Judaism and Haredi Judaism (Chasidic Chabad) but can actually include a wide range of beliefs. Orthodoxy collectively considers itself the only true heir to the Jewish tradition. The Orthodox Jewish movements generally consider all non-Orthodox Jewish movements to be unacceptable deviations from authentic Judaism; both because of other denominations' doubt concerning the verbal revelation of Written and Oral Torah, and because of their rejection of Halakhic precedent as binding. As such, Orthodox groups characterize non-Orthodox forms of Judaism as heretical Reform Judaism is a phrase that refers to various beliefs, practices and organizations associated with the Reform Jewish movement in North America, the United Kingdom and elsewhere.[1] In general, Reform Judaism maintains that Judaism and Jewish traditions should be modernized and compatible with participation in the surrounding culture. Many branches of Reform Judaism hold that Jewish law should be interpreted as a set of general guidelines rather than as a list of restrictions whose literal observance is required of all Jews.[2][3] Similar movements that are also occasionally called "Reform" include the Israeli Progressive Movement and its worldwide counterpart. -

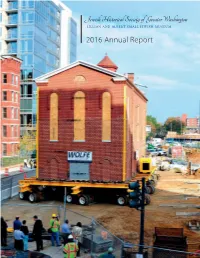

2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report 209455_Annual Report.indd 1 8/4/17 9:56 AM Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington LILLIAN AND ALBERT SMALL JEWISH MUSEUM 2016 Major Achievements The Society . • Held our last program in the Lillian & Albert Small Jewish Museum on the 140th anniversary of the historic 1876 synagogue. • Moved the synagogue 50 feet into the intersection of Third & G – the first step on its journey to a new home and the Society’s new Museum. • Received national coverage of the historic synagogue move from The Washington Post, The New York Times, Associated Press, and other news outlets. By the Numbers . • 17 youth programs served 451 students. • 3,275 adults participated in 81 programs at 30 venues. • 19 donors contributed more than 100 photographs, 30 boxes of archival documents, and 14 objects to the archives. • 70 historians, students, media outlets, organizations, and genealogists around the globe received answers to their research requests. • 34,094 website visits from 148 countries, 3,263 YouTube video views, and 1,281 Facebook fans. • 31 volunteers contributed more than 350 hours. The publication of this Annual Report was made possible, in part, with support from the Rosalie Fonoroff Endowment Fund. 209455_Annual Report.indd 2 8/4/17 9:56 AM 1 Leadership Message THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT OF OUR WORK IN 2016! hakespeare wrote that “What’s past is prologue,” describing Finally, we bid farewell to longtime Executive Director, Laura elegantly how history sets the context for the present. Apelbaum, who resigned after 22 years of committed service. SThe same maxim describes the point at which the Jewish During her tenure, the Society expanded its activities on every Historical Society of Greater Washington finds itself in 2017: level, gained a reputation for excellent programming and sound moving forward to design, finance and ultimately build a administration, and laid the groundwork for the successful wonderful new museum, archive, and venue for education, completion of the new museum. -

Information Issued by The

Vol. XV No. 10 October, 1960 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE. ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN t FAIRFAX MANSIONS, FINCHLEY ROAD (Comer Fairfax Road), Offict and Consulting Hours : LONDON, N.W.3 Monday to Thursday 10 a.m.—I p.m. 3—6 p.m. Talephona: MAIda Vala 9096'7 (General Officel Friday 10 a.m.—I p.m. MAIda Vale 4449 (Employment Agency and Social Services Dept.} 'Rudolf Hirschfeld (Monlevideo) a few others. Apart from them, a list of the creators of all these important German-Jewish organisations in Latin America would hardly con tain a name of repute outside the continent. It GERMAN JEWS IN SOUTH AMERICA it without any doubt a good sign that post-1933 German Jewry has been able to produce an entirely new generation of vigorous and success I he history of the German-Jewish organisations abroad '"—to assert this would be false—they ful leaders. =8ins in each locality the moment the first ten consider themselves as the sons of the nation In conclusion two further aspects have to be r^Ple from Germany disembark. In the few which has built up the State of Israel, with the mentioned : the relationship with the Jews around thp "if- ^^^^^ Jewish groups were living before consciousness that now at last they are legitimate us, and the future of the community of Jews from ne Hitler period the immigrants were helped by members of the national families of the land they Central Europe. Jewish life in South America ne earlier arrivals. But it is interesting that this inhabit at present. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission the Lambeth-Jewish Forum

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Reuven Silverman, Patrick Morrow and Daniel Langton Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Both Christianity and Judaism have a vocation to mission. In the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, God’s people are spoken of as a light to the nations. Yet mission is one of the most sensitive and divisive areas in Jewish-Christian relations. For Christians, mission lies at the heart of their faith because they understand themselves as participating in the mission of God to the world. As the recent Anglican Communion document, Generous Love, puts it: “The boundless life and perfect love which abide forever in the heart of the Trinity are sent out into the world in a mission of renewal and restoration in which we are called to share. As members of the Church of the Triune God, we are to abide among our neighbours of different faiths as signs of God’s presence with them, and we are sent to engage with our neighbours as agents of God’s mission to them.”1 As part of the lifeblood of Christian discipleship, mission has been understood and worked out in a wide range of ways, including teaching, healing, evangelism, political involvement and social renewal. Within this broad and rich understanding of mission, one key aspect is the relation between mission and evangelism. In particular, given the focus of the Lambeth-Jewish Forum, how does the Christian understanding of mission affects relations between Christianity and Judaism? Christian mission and Judaism has been controversial both between Christians and Jews, and among Christians themselves. -

“As Those Who Are Taught” Symposium Series

“AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Symposium Series Christopher R. Matthews, Editor Number 27 “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL Edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Copyright © 2006 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data “As those who are taught” : the interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL / edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull. p. cm. — (Society of biblical literature symposium series ; no. 27) Includes indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-58983-103-2 (paper binding : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-58983-103-9 (paper binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T. Isaiah—Criticism, interpretation, etc.—History. 2. Bible. O.T. Isaiah— Versions. 3. Bible. N.T.—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. McGinnis, Claire Mathews. II. Tull, Patricia K. III. Series: Symposium series (Society of Biblical Literature) ; no. 27. BS1515.52.A82 2006 224'.10609—dc22 2005037099 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

The Semitic Component in Yiddish and Its Ideological Role in Yiddish Philology

philological encounters � (�0�7) 368-387 brill.com/phen The Semitic Component in Yiddish and its Ideological Role in Yiddish Philology Tal Hever-Chybowski Paris Yiddish Center—Medem Library [email protected] Abstract The article discusses the ideological role played by the Semitic component in Yiddish in four major texts of Yiddish philology from the first half of the 20th century: Ysroel Haim Taviov’s “The Hebrew Elements of the Jargon” (1904); Ber Borochov’s “The Tasks of Yiddish Philology” (1913); Nokhem Shtif’s “The Social Differentiation of Yiddish: Hebrew Elements in the Language” (1929); and Max Weinreich’s “What Would Yiddish Have Been without Hebrew?” (1931). The article explores the ways in which these texts attribute various religious, national, psychological and class values to the Semitic com- ponent in Yiddish, while debating its ontological status and making prescriptive sug- gestions regarding its future. It argues that all four philologists set the Semitic component of Yiddish in service of their own ideological visions of Jewish linguistic, national and ethnic identity (Yiddishism, Hebraism, Soviet Socialism, etc.), thus blur- ring the boundaries between descriptive linguistics and ideologically engaged philology. Keywords Yiddish – loshn-koydesh – semitic philology – Hebraism – Yiddishism – dehebraization Yiddish, although written in the Hebrew alphabet, is predominantly Germanic in its linguistic structure and vocabulary.* It also possesses substantial Slavic * The comments of Yitskhok Niborski, Natalia Krynicka and of the anonymous reviewer have greatly improved this article, and I am deeply indebted to them for their help. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/�45�9�97-��Downloaded34003� from Brill.com09/23/2021 11:50:14AM via free access The Semitic Component In Yiddish 369 and Semitic elements, and shows some traces of the Romance languages. -

Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-13-2017 Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation White, James Jefferson. "Jewish Culture in the Christian World." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/207 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James J White Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Sarah Davis-Secord, Chairperson Timothy Graham Michael Ryan i JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD by JAMES J WHITE PREVIOUS DEGREES BACHELORS THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2017 ii JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD BY James White B.S., History, University of North Texas, 2013 M.A., History, University of New Mexico, 2017 ABSTRACT Christians constantly borrowed the culture of their Jewish neighbors and adapted it to Christianity. This adoption and appropriation of Jewish culture can be fit into three phases. The first phase regarded Jewish religion and philosophy. From the eighth century to the thirteenth century, Christians borrowed Jewish religious exegesis and beliefs in order to expand their own understanding of Christian religious texts. -

Lenin-S-Jewish-Question

Lenin’s Jewish Question Lenin’s Jewish Question YOHANAN PETROVSKY-SHTERN New Haven and London Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College. Copyright © 2010 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Set in Minion type by Integrated Publishing Solutions. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petrovskii-Shtern, Iokhanan. Lenin’s Jewish question / Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-15210-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Relations with Jews. 2. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Family. 3. Ul’ianov family. 4. Lenin, Vladimir Il’ich, 1870–1924—Public opinion. 5. Jews— Identity—Case studies. 6. Jewish question. 7.Jews—Soviet Union—Social conditions. 8. Jewish communists—Soviet Union—History. 9. Soviet Union—Politics and government. I. Title. DK254.L46P44 2010 947.084'1092—dc22 2010003985 This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Estonian Yiddish and Its Contacts with Coterritorial Languages

DISSERT ATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU 2000 DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES Eesti jidiš ja selle kontaktid Eestis kõneldavate keeltega ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU UNIVERSITY PRESS Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University o f Tartu, Tartu, Estonia Dissertation is accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in general linguistics) on December 22, 1999 by the Doctoral Committee of the Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Tartu Supervisor: Prof. Tapani Harviainen (University of Helsinki) Opponents: Professor Neil Jacobs, Ohio State University, USA Dr. Kristiina Ross, assistant director for research, Institute of the Estonian Language, Tallinn Commencement: March 14, 2000 © Anna Verschik, 2000 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tiigi 78, Tartu 50410 Tellimus nr. 53 ...Yes, Ashkenazi Jews can live without Yiddish but I fail to see what the benefits thereof might be. (May God preserve us from having to live without all the things we could live without). J. Fishman (1985a: 216) [In Estland] gibt es heutzutage unter den Germanisten keinen Forscher, der sich ernst für das Jiddische interesiere, so daß die lokale jiddische Mundart vielleicht verschwinden wird, ohne daß man sie für die Wissen schaftfixiert -

Lenin a Revolutionary Life

lenin ‘An excellent biography, which captures the real Lenin – part intel- lectual professor, part ruthless and dogmatic politician.’ Geoffrey Swain, University of the West of England ‘A fascinating book about a gigantic historical figure. Christopher Read is an accomplished scholar and superb writer who has pro- duced a first-rate study that is courageous, original in its insights, and deeply humane.’ Daniel Orlovsky, Southern Methodist University Vladimir Il’ich Ulyanov, known as Lenin was an enigmatic leader, a resolute and audacious politician who had an immense impact on twentieth-century world history. Lenin’s life and career have been at the centre of much ideological debate for many decades. The post-Soviet era has seen a revived interest and re-evaluation of the Russian Revolution and Lenin’s legacy. This new biography gives a fresh and original account of Lenin’s personal life and political career. Christopher Read draws on a broad range of primary and secondary sources, including material made available in the glasnost and post-Soviet eras. Focal points of this study are Lenin’s revolutionary ascetic personality; how he exploited culture, education and propaganda; his relationship to Marxism; his changing class analysis of Russia; and his ‘populist’ instincts. This biography is an excellent and reliable introduction to one of the key figures of the Russian Revolution and post-Tsarist Russia. Christopher Read is Professor of Modern European History at the University of Warwick. He is author of From Tsar to Soviets: The Russian People and Their Revolution, 1917–21 (1996), Culture and Power in Revolutionary Russia (1990) and The Making and Breaking of the Soviet System (2001).