Metternich Viennacongress 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, the Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), Ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, E

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, The Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), ix. 2. Michael Broers, Europe under Napoleon, 1799–1815 (London, 1996), 3. 3. An exception to the Franco-centric bibliography in English prior to the last decade is Owen Connelly, Napoleon’s Satellite Kingdoms (New York, 1965). Connelly discusses the developments in five satellite kingdoms: Italy, Naples, Holland, Westphalia, and Spain. Two other important works that appeared before 1990, which explore the internal developments in two countries during the Napoleonic period, are Gabriel Lovett, Napoleon and the Birth of Modern Spain (New York, 1965) and Simon Schama, Patriots and Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands, 1780–1813 (London, 1977). 4. Stuart Woolf, Napoleon’s Integration of Europe (London and New York, 1991), 8–13. 5. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 102–5; Broers, Europe under Napoleon, passim. 1 THE FORMATION OF THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE 1. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 105. 2. Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (New York, 1994), 43. 3. Ellis, “The Nature,” 104–5. 4. On the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and international relations, see Tim Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787–1802 (London, 1996); David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon: the Mind and Method of History’s Greatest Soldier (London, 1966); Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military 212 Notes 213 Campaigns (Wilmington, DE, 1987); J. -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Appanage Russia

0 BACKGROUND GUIDE: APPANAGE RUSSIA 1 BACKGROUND GUIDE: APPANAGE RUSSIA Hello delegates, My name is Paul, and I’ll be your director for this year. Working with me are your moderator, Tristan; your crisis manager, Davis; and your analysts, Lawrence, Lilian, Philip, and Sofia. We’re going to be working together to make this council as entertaining and educational (yeah yeah, I know) as possible. A bit about me? I am a third year student studying archaeology, and this is also my third year doing UTMUN. Now enough about me. Let’s talk about something far more interesting: Russia. Russian history is as brutal as the land itself, especially during our time of study. Geography sets the stage with freezing winters and mud-ridden summers. This has huge effects on how Russia’s economy and society functions. Coupled with that are less-than-neighbourly neighbours: the power- hungry nations of western and central Europe, The Byzantine Empire (a consistent love- hate partner), and (big surprise) various nomadic groups, one of which would eventually pose quite a problem for the idea of Russian independence. Uh oh, it looks like it’s suddenly 1300 and all of you are Russian Princess.You are all under the rule of Toqta Khan of the Golden Horde (Halperin, 2009), one of the successor states to Genghis Khan’s massive empire. Bummer. But, there is hope: through working together and with wise reactions to the crises that will inevitably come your way, you might just be able shake off the Tatar Yoke. Of course, your problems are not so limited. -

Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe European History in Perspective General Editor: Jeremy Black

Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe European History in Perspective General Editor: Jeremy Black Benjamin Arnold Medieval Germany Ronald Asch The Thirty Years’ War Christopher Bartlett Peace, War and the European Powers, 1814–1914 Robert Bireley The Refashioning of Catholicism, 1450–1700 Donna Bohanan Crown and Nobility in Early Modern France Arden Bucholz Moltke and the German Wars, 1864–1871 Patricia Clavin The Great Depression, 1929–1939 Paula Sutter Fichtner The Habsburg Monarchy, 1490–1848 Mark Galeotti Gorbachev and his Revolution David Gates Warfare in the Nineteenth Century Alexander Grab Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe Martin P. Johnson The Dreyfus Affair Peter Musgrave The Early Modern European Economy J. L. Price The Dutch Republic in the Seventeenth Century A. W. Purdue The Second World War Christopher Read The Making and Breaking of the Soviet System Francisco J. Romero-Salvado Twentieth-Century Spain Matthew S. Seligmann and Roderick R. McLean Germany from Reich to Republic, 1871–1918 Brendan Simms The Struggle for Mastery in Germany, 1779–1850 David Sturdy Louis XIV Hunt Tooley The Western Front Peter Waldron The End of Imperial Russia, 1855–1917 Peter G. Wallace The Long European Reformation James D. White Lenin Patrick Williams Philip II European History in Perspective Series Standing Order ISBN 978-0-333-71694-6 hardcover ISBN 978-0-333-69336-0 paperback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in the case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and the ISBN quoted above. -

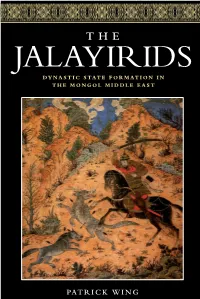

The Jalayirids Dynastic State Formation in the Mongol Middle East

THE JALAYIRIDS DYNASTIC STATE FORMATION IN THE MONGOL MIDDLE EAST 1 PATRICK WING THE JALAYIRIDS The Royal Asiatic Society was founded in 1823 ‘for the investigation of subjects connected with, and for the encouragement of science, literature and the arts in relation to Asia’. Informed by these goals, the policy of the Society’s Editorial Board is to make available in appropriate formats the results of original research in the humanities and social sciences having to do with Asia, defined in the broadest geographical and cultural sense and up to the present day. The Monograph Board Professor Francis Robinson CBE, Royal Holloway, University of London (Chair) Professor Tim Barrett, SOAS, University of London Dr Evrim Binbas¸, Royal Holloway, University of London Dr Barbara M. C. Brend Professor Anna Contadini, SOAS, University of London Professor Michael Feener, National University of Singapore Dr Gordon Johnson, University of Cambridge Dr Rosie Llewellyn Jones MBE Professor David Morgan, University of Wisconsin- Madison Professor Rosalind O’Hanlon, University of Oxford Dr Alison Ohta, Director, Royal Asiatic Society For a full list of publications by the Royal Asiatic Society see www.royalasiaticsociety.org THE JALAYIRIDS DYNASTIC STATE FORMATION IN THE MONGOL MIDDLE EAST 2 Patrick Wing For E. L., E. L. and E. G. © Patrick Wing, 2016 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11 /13 JaghbUni Regular by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 0225 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0226 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 1093 9 (epub) The right of Patrick Wing to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. -

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic, Industrial And

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic and Military Mobilization in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) By Ioannis-Dionysios Salavrakos The Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era lasted from 1792 to 1815. During this period, seven Anti-French Coalitions were formed ; France managed to get the better of the first five of them. The First Coalition was formed between Austria and Prussia (26 June 1792) and was reinforced by the entry of Britain (January 1793) and Spain (March 1793). Minor participants were Tuscany, Naples, Holland and Russia. In February 1795, Tuscany left and was followed by Prussia (April); Holland (May), Spain (August). In 1796, two other Italian States (Piedmont and Sardinia) bowed out. In October 1797, Austria was forced to abandon the alliance : the First Coalition collapsed. The Second Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Naples and the Ottoman Empire (22 June 1799), was terminated on March 25, 1802. A Third Coalition, which comprised Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Sweden, and some small German principalities (April 1805), collapsed by December the same year. The Fourth Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria and Russia, came in October 1806 but was soon aborted (February 1807). The Fifth Coalition, established between Britain, Austria, Spain and Portugal (April 9th, 1809) suffered the same fate when, on October 14, 1809, Vienna surrendered to the French – although the Iberian Peninsula front remained active. Thus until 1810 France had faced five coalitions with immense success. The tide began to turn with the French campaign against Russia (June 1812), which precipitated the Sixth Coalition, formed by Russia and Britain, and soon joined by Spain, Portugal, Austria, Prussia, Sweden and other small German States. -

The Great European Treaties of the Nineteenth Century

JBRART Of 9AN DIEGO OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY EDITED BY SIR AUGUSTUS OAKES, CB. LATELY OF THE FOREIGN OFFICE AND R. B. MOWAT, M.A. FELLOW AND ASSISTANT TUTOR OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, OXFORD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR H. ERLE RICHARDS K. C.S.I., K.C., B.C.L., M.A. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE AWD CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND DIPLOMACY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASSOCIATE OF THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW LEIPZIG NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY Impression of 1930 First edition, 1918 Printed in Great Britain INTRODUCTION IT is now generally accepted that the substantial basis on which International Law rests is the usage and practice of nations. And this makes it of the first importance that the facts from which that usage and practice are to be deduced should be correctly appre- ciated, and in particular that the great treaties which have regulated the status and territorial rights of nations should be studied from the point of view of history and international law. It is the object of this book to present materials for that study in an accessible form. The scope of the book is limited, and wisely limited, to treaties between the nations of Europe, and to treaties between those nations from 1815 onwards. To include all treaties affecting all nations would require volumes nor is it for the many ; necessary, purpose of obtaining a sufficient insight into the history and usage of European States on such matters as those to which these treaties relate, to go further back than the settlement which resulted from the Napoleonic wars. -

Alexander Grab: Conscription and Desertion in France and Italy Under

Alexander Grab: Conscription and Desertion in France and Italy under Napoleon Schriftenreihe Bibliothek des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom Band 127 (2013) Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Rom Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat der Creative- Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) unterliegt. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Den Text der Lizenz erreichen Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode ALEX A NDER GR A B Conscription and Desertion in France and Italy under Napoleon It is by now a commonplace that Napoleon depended on the human and fiscal resources of Europe in his drive for imperial expansion and domination. The French emperor would have been unable to expand and maintain his empire without the money and troops that occupied Europe supplied him. A key to his ability to tap into the human resources of his European satellites was an annual and effective conscription system. In September 1798 the French gov- ernment introduced a yearly conscription program and quickly extended it to the Belgian départements and the Cisalpine Republic.1 Prior to the Revolution, armies largely consisted of volunteers and mercenaries. While some form of draft had existed in parts of pre-Revolutionary Europe – France had an ob- ligatory militia system to supplement the regular army – Napoleon increased it to unprecedented levels and extended it to states that previously had not experienced it. -

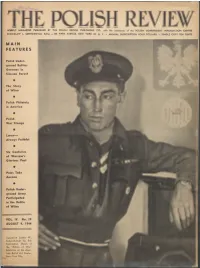

Main Features

WEEKLY MAGAZINE PUBUSHED BY THE POLISH REVIEW PUBLISHING CO., with the assistance of the POLISH GOVERNMENT INFORMATION CENTER STANISLAW L CENTKIEWICZ, Editor —745 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK 22, N. Y. • ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION FOUR DOLLARS • SINGLE COPY TEN CENTS MAIN FEATURES Polish Under ground Battles Germans in Silesian Forest The Story of Wilno Polish Philately in America Polish War Stamps Lwow— Always Faithful Six Centuries of Warsaw's Glorious Past Poles Take Ancona Polish Under ground Army Participated in the Battle of Wilno VOL IV. No. 29 AUGUST 9. 1944 Squadron Leader W. Kołaczkowski by Eric Kennington. Shown at the "Britain at War" Exhibition at the Amer ican British Art Center, New York City. "Grant us a sense of power, Lord Grant us a living Poland, pray. Polish Minister of Interior Broadcasts to Poland Make manifest the promised Word In our unhappy land today.” —Stanislaw Wyspiański (1869-1907) Minister Wladyslaw Banaczyk broadcasting to Poland on July 27 said in part: "In the present situation the Polish Government is forced to disclose, despite the danger of betrayal and of German Polish Underground Battles Germans InSilesianForest reprisals, that in the Polish Underground there are functioning the Guerrilla warfare in Poland has never for a moment ceased trained for man-hunting come to wipe out our formidable Deputy-Premier of the Polish Government and three Ministers: throughout the five years of German oppression. Partisan detachment. They set up machine-gun nests at every cross Wlakowicz, Traugutt and Polski. groups dot the countryside, and are particularly numerous in ing of forest paths. So tight is their net that no one could the wilder, wooded regions of Poland. -

Amphora Graffiti from the Byzantine Shipwreck at Novy Svet, Crimea

AMPHORA GRAFFITI FROM THE BYZANTINE SHIPWRECK AT NOVY SVET, CRIMEA A Thesis by CLAIRE ALIKI COLLINS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Deborah Carlson Committee Members, Filipe Vieira de Castro Nancy Klein Head of Department, Cynthia Werner December 2012 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2012 Claire Aliki Collins ABSTRACT The thesis presents the results of a study of 1005 graffiti on 13th century Byzantine amphorae from a shipwreck in the Bay of Sudak near Novy Svet, Crimea, Ukraine. The primary goals of this thesis are 1) to provide an overview of the excavation and shipwreck, 2) to examine the importance of the Novy Svet wreck in terms of Black Sea maritime trade in the Late Byzantine period, 3) to present the data collected at the Center for Underwater Archaeology at the Taras Shevchenko National University in Kiev, Ukraine (CUA) about the graffiti inscribed on the Günsenin IV amphorae raised from the Novy Svet wreck and 4) to discuss the meaning and importance of the graffiti, both aboard the ship itself and in a more general context. The thesis introduces the results of the 2002-2008 underwater excavation seasons at Novy Svet. Excavators have identified a 13th century shipwreck filled with glazed ceramics and amphorae as a Pisan vessel sunk on August 14, 1277. The majority of the amphorae are Günsenin IV jars and have graffiti inscribed on them. Analysis of the graffiti focuses on the division of the marks into morphological categories, and identifying parallels for the specific forms at other archaeological sites. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

League of the Public Weal, 1465

League of the Public Weal, 1465 It is not necessary to hope in order to undertake, nor to succeed in order to persevere. —Charles the Bold Dear Delegates, Welcome to WUMUNS 2018! My name is Josh Zucker, and I am excited to be your director for the League of the Public Weal. I am currently a junior studying Systems Engineering and Economics. I have always been interested in history (specifically ancient and medieval history) and politics, so Model UN has been a perfect fit for me. Throughout high school and college, I’ve developed a passion for exciting Model UN weekends, and I can’t wait to share one with you! Louis XI, known as the Universal Spider for his vast reach and ability to weave himself into all affairs, is one of my favorite historical figures. His continual conflicts with Charles the Bold of Burgundy and the rest of France’s nobles are some of the most interesting political struggles of the medieval world. Louis XI, through his tireless work, not only greatly transformed the monarchy but also greatly strengthened France as a kingdom and set it on its way to becoming the united nation we know today. This committee will transport you to France as it reinvents itself after the Hundred Years War. Louis XI, the current king of France, is doing everything in his power to reform and reinvigorate the French monarchy. Many view his reign as tyranny. You, the nobles of France, strive to keep the monarchy weak. For that purpose, you have formed the League of the Public Weal.