Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe European History in Perspective General Editor: Jeremy Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, the Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), Ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, E

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, The Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), ix. 2. Michael Broers, Europe under Napoleon, 1799–1815 (London, 1996), 3. 3. An exception to the Franco-centric bibliography in English prior to the last decade is Owen Connelly, Napoleon’s Satellite Kingdoms (New York, 1965). Connelly discusses the developments in five satellite kingdoms: Italy, Naples, Holland, Westphalia, and Spain. Two other important works that appeared before 1990, which explore the internal developments in two countries during the Napoleonic period, are Gabriel Lovett, Napoleon and the Birth of Modern Spain (New York, 1965) and Simon Schama, Patriots and Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands, 1780–1813 (London, 1977). 4. Stuart Woolf, Napoleon’s Integration of Europe (London and New York, 1991), 8–13. 5. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 102–5; Broers, Europe under Napoleon, passim. 1 THE FORMATION OF THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE 1. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 105. 2. Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (New York, 1994), 43. 3. Ellis, “The Nature,” 104–5. 4. On the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and international relations, see Tim Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787–1802 (London, 1996); David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon: the Mind and Method of History’s Greatest Soldier (London, 1966); Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military 212 Notes 213 Campaigns (Wilmington, DE, 1987); J. -

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic, Industrial And

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic and Military Mobilization in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) By Ioannis-Dionysios Salavrakos The Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era lasted from 1792 to 1815. During this period, seven Anti-French Coalitions were formed ; France managed to get the better of the first five of them. The First Coalition was formed between Austria and Prussia (26 June 1792) and was reinforced by the entry of Britain (January 1793) and Spain (March 1793). Minor participants were Tuscany, Naples, Holland and Russia. In February 1795, Tuscany left and was followed by Prussia (April); Holland (May), Spain (August). In 1796, two other Italian States (Piedmont and Sardinia) bowed out. In October 1797, Austria was forced to abandon the alliance : the First Coalition collapsed. The Second Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Naples and the Ottoman Empire (22 June 1799), was terminated on March 25, 1802. A Third Coalition, which comprised Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Sweden, and some small German principalities (April 1805), collapsed by December the same year. The Fourth Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria and Russia, came in October 1806 but was soon aborted (February 1807). The Fifth Coalition, established between Britain, Austria, Spain and Portugal (April 9th, 1809) suffered the same fate when, on October 14, 1809, Vienna surrendered to the French – although the Iberian Peninsula front remained active. Thus until 1810 France had faced five coalitions with immense success. The tide began to turn with the French campaign against Russia (June 1812), which precipitated the Sixth Coalition, formed by Russia and Britain, and soon joined by Spain, Portugal, Austria, Prussia, Sweden and other small German States. -

The Great European Treaties of the Nineteenth Century

JBRART Of 9AN DIEGO OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY EDITED BY SIR AUGUSTUS OAKES, CB. LATELY OF THE FOREIGN OFFICE AND R. B. MOWAT, M.A. FELLOW AND ASSISTANT TUTOR OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, OXFORD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY SIR H. ERLE RICHARDS K. C.S.I., K.C., B.C.L., M.A. FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE AWD CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND DIPLOMACY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASSOCIATE OF THE INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW LEIPZIG NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY Impression of 1930 First edition, 1918 Printed in Great Britain INTRODUCTION IT is now generally accepted that the substantial basis on which International Law rests is the usage and practice of nations. And this makes it of the first importance that the facts from which that usage and practice are to be deduced should be correctly appre- ciated, and in particular that the great treaties which have regulated the status and territorial rights of nations should be studied from the point of view of history and international law. It is the object of this book to present materials for that study in an accessible form. The scope of the book is limited, and wisely limited, to treaties between the nations of Europe, and to treaties between those nations from 1815 onwards. To include all treaties affecting all nations would require volumes nor is it for the many ; necessary, purpose of obtaining a sufficient insight into the history and usage of European States on such matters as those to which these treaties relate, to go further back than the settlement which resulted from the Napoleonic wars. -

Alexander Grab: Conscription and Desertion in France and Italy Under

Alexander Grab: Conscription and Desertion in France and Italy under Napoleon Schriftenreihe Bibliothek des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom Band 127 (2013) Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Rom Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat der Creative- Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) unterliegt. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Den Text der Lizenz erreichen Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode ALEX A NDER GR A B Conscription and Desertion in France and Italy under Napoleon It is by now a commonplace that Napoleon depended on the human and fiscal resources of Europe in his drive for imperial expansion and domination. The French emperor would have been unable to expand and maintain his empire without the money and troops that occupied Europe supplied him. A key to his ability to tap into the human resources of his European satellites was an annual and effective conscription system. In September 1798 the French gov- ernment introduced a yearly conscription program and quickly extended it to the Belgian départements and the Cisalpine Republic.1 Prior to the Revolution, armies largely consisted of volunteers and mercenaries. While some form of draft had existed in parts of pre-Revolutionary Europe – France had an ob- ligatory militia system to supplement the regular army – Napoleon increased it to unprecedented levels and extended it to states that previously had not experienced it. -

Main Features

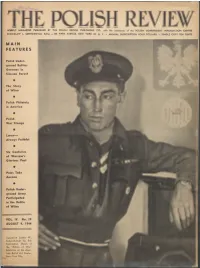

WEEKLY MAGAZINE PUBUSHED BY THE POLISH REVIEW PUBLISHING CO., with the assistance of the POLISH GOVERNMENT INFORMATION CENTER STANISLAW L CENTKIEWICZ, Editor —745 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK 22, N. Y. • ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION FOUR DOLLARS • SINGLE COPY TEN CENTS MAIN FEATURES Polish Under ground Battles Germans in Silesian Forest The Story of Wilno Polish Philately in America Polish War Stamps Lwow— Always Faithful Six Centuries of Warsaw's Glorious Past Poles Take Ancona Polish Under ground Army Participated in the Battle of Wilno VOL IV. No. 29 AUGUST 9. 1944 Squadron Leader W. Kołaczkowski by Eric Kennington. Shown at the "Britain at War" Exhibition at the Amer ican British Art Center, New York City. "Grant us a sense of power, Lord Grant us a living Poland, pray. Polish Minister of Interior Broadcasts to Poland Make manifest the promised Word In our unhappy land today.” —Stanislaw Wyspiański (1869-1907) Minister Wladyslaw Banaczyk broadcasting to Poland on July 27 said in part: "In the present situation the Polish Government is forced to disclose, despite the danger of betrayal and of German Polish Underground Battles Germans InSilesianForest reprisals, that in the Polish Underground there are functioning the Guerrilla warfare in Poland has never for a moment ceased trained for man-hunting come to wipe out our formidable Deputy-Premier of the Polish Government and three Ministers: throughout the five years of German oppression. Partisan detachment. They set up machine-gun nests at every cross Wlakowicz, Traugutt and Polski. groups dot the countryside, and are particularly numerous in ing of forest paths. So tight is their net that no one could the wilder, wooded regions of Poland. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

In Time, Napoleon's Battlefield Successes Forced the Rulers Of

In time, Napoleon’s battlefield successes forced the rulers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia to sign peace treaties. These successes also enabled him to build the largest European empire since that of the Romans. France’s only major enemy left unde- feated was the great naval power, Britain. The Battle of Trafalgar In his drive for a European empire, Napoleon lost only one major battle, the Battle of Trafalgar (truh•FAL•guhr). This naval defeat, how- ever, was more important than all of his victories on land. The battle took place in 1805 off the southwest coast of Spain. The British commander, Horatio Nelson, was as brilliant in warfare at sea as Napoleon was in warfare on land. In a bold maneuver, he split the larger French fleet, capturing many ships. (See the map inset on the opposite page.) The destruction of the French fleet had two major results. First, it ensured the supremacy of the British navy for the next 100 years. Second, it forced Napoleon to give up his plans of invading Britain. He had to look for another way to control his powerful enemy across the English Channel. Eventually, Napoleon’s extrava- gant efforts to crush Britain would lead to his own undoing. The French Empire During the first decade of the 1800s, Napoleon’s victories had given him mastery over most of Europe. By 1812, the only areas of Europe free from Napoleon’s control were Britain, Portugal, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the lands of the French Empire, Napoleon also controlled numerous supposedly independent countries. -

The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Vol. III

The Life Of Napoleon Bonaparte. Vol. III. By William Milligan Sloane LIFE OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE CHAPTER I. WAR WITH RUSSIA: PULTUSK. Poland and the Poles — The Seat of War — Change in the Character of Napoleon's Army — The Battle of Pultusk — Discontent in the Grand Army — Homesickness of the French — Napoleon's Generals — His Measures of Reorganization — Weakness of the Russians — The Ability of Bennigsen — Failure of the Russian Manœuvers — Napoleon in Warsaw. 1806-07. The key to Napoleon's dealings with Poland is to be found in his strategy; his political policy never passed beyond the first tentative stages, for he never conquered either Russia or Poland. The struggle upon which he was next to enter was a contest, not for Russian abasement but for Russian friendship in the interest of his far-reaching continental system. Poland was simply one of his weapons against the Czar. Austria was steadily arming; Francis received the quieting assurance that his share in the partition was to be undisturbed. In the general and proper sorrow which has been felt for the extinction of Polish nationality by three vulture neighbors, the terrible indictment of general worthlessness which was justly brought against her organization and administration is at most times and by most people utterly forgotten. A people has exactly the nationality, government, and administration which expresses its quality and secures its deserts. The Poles were either dull and sluggish boors or haughty and elegant, pleasure- loving nobles. Napoleon and his officers delighted in the life of Warsaw, but he never appears to have respected the Poles either as a whole or in their wrangling cliques; no doubt he occasionally faced the possibility of a redeemed Poland, but in general the suggestion of such a consummation served his purpose and he went no further. -

Metternich Viennacongress 18

Habsburg H-Net Discussion Network Prince Metternich, On the Vienna Congress, 1815 Source: http://www.h-net.org/~habsweb/sourcetexts/vienna.htm Prince Richard Metternich, ed. MEMOIRS OF PRINCE METTERNICH, 1773-1815. Volume II. Translated by Mrs. Alexander Napier. Classified and arranged by M.A. de Klinkowstrom. New York: Howard Fertig, 1970. [p. 553] AT THE TIME OF THE BEGINNING OF THE PEACE ERA. 1815 THE VIENNA CONGRESS (Note 80, Vol. I.) 192. Memoir by Frederick von Gentz, February 12, 1815. 193. Metternich to Hardenberg, Vienna, December 10, 1814. 194. Talleyrand to Metternich, Vienna, December 12, 1814. 192. Those who at the time of the assembling of the Congress at Vienna had thoroughly understood the nature and objects of this Congress, could hardly have been mistaken about its course, whatever their opinion about its results might be. The grand phrases of "reconstruction of social order," "regeneration of the political system of Europe," "a lasting peace founded on a just division of strength," &c., &c., were uttered to tran- quillise the people, and to give an air of dignity and grandeur to this solemn assembly; but the real purpose of the congress was to divide amongst the conquerors the spoils taken from the vanquished. The comprehension of this truth enables us to foresee that the discussions of this Congress would be difficult, painful, and often stormy. But to understand how far they have been so, and why the hopes of so many enlightened men, but more or less ignorant of cabinet secrets, have been so cruelly disappointed, one must know the designs which the principal Powers had in presenting [p. -

Appendix 1: Dynasty, Nobility and Notables of the Napoleonic Empire

Appendix 1: Dynasty, Nobility and Notables of the Napoleonic Empire A Napoleon Emperor of the French, Jg o~taly, Mediator of the Swiss Confederation, Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine, etc. Princes of the first order: memtrs of or\ose related by marriage to the Imperial family who became satellite kings: Joseph, king of Naples (March 1806) and then of Spain (June 1808); Louis, king of Holland (June 1806-July 1810); Ur6me, king of Westphalia (July 1807); Joachim Murat (m. Caroline Bonaparte), grand duke of Berg (March 1806) and king of Naples (July 1808) Princes(ses) of the selnd order: Elisa Bo~e (m. F6lix Bacciochi), princess of Piombino (1805) and of Lucca (1806), grand duchess of Tuscany (1809); Eug~ne de Beauharnais, viceroy ofltaly (June 1805); Berthier, prince ofNeuchitel (March 1806) and of Wagram (December 1809) Princes of the J order: Talleyrand, prince of Bene\ento (June 1806); Bernadotte, prince of Ponte Corvo (June 1806) [crown prince of Sweden, October 1810] The 22 recipien! of the 'ducal grand-fiefs of the Empire'\.eated in March 1806 from conquered lands around Venice, in the kingdom of Naples, in Massa-Carrara, Parma and Piacenza. Similar endowments were later made from the conquered lands which formed the duchy of Warsaw (July 1807) These weret.anted to Napoleon's top military commanders, in\uding most of the marshals, or to members of his family, and were convertible into hereditary estates (majorats) The duk!s, counts, barons and chevaliers of the Empire created after le March decrees of 1808, and who together -

Napoleon Forges an Empire

3 Napoleon Forges an Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES POWER AND AUTHORITY In times of political turmoil, • Napoleon • concordat Napoleon Bonaparte, a military military dictators often seize Bonaparte •Napoleonic genius, seized power in France control of nations. •coup d’état Code and made himself emperor. • plebiscite • Battle of •lycée Trafalgar SETTING THE STAGE Napoleon Bonaparte was quite a short man—just five feet three inches tall. However, he cast a long shadow over the history of mod- ern times. He would come to be recognized as one of the world’s greatest mil- itary geniuses, along with Alexander the Great of Macedonia, Hannibal of Carthage, and Julius Caesar of Rome. In only four years, from 1795 to 1799, Napoleon rose from a relatively obscure position as an officer in the French army to become master of France. Napoleon Seizes Power TAKING NOTES Following Chronological Napoleon Bonaparte was born in 1769 on the Mediterranean island of Corsica. Order On a time line, note When he was nine years old, his parents sent him to a military school. In 1785, the events that led to at the age of 16, he finished school and became a lieutenant in the artillery. When Napoleon’s crowning as the Revolution broke out, Napoleon joined the army of the new government. emperor of France. Hero of the Hour In October 1795, fate handed the young officer a chance for glory. When royalist rebels marched on the National Convention, a government 1789 1804 official told Napoleon to defend the delegates. Napoleon and his gunners greeted French Napoleon the thousands of royalists with a cannonade. -

The Constitution of the Duchy of Warsaw 1807. Some Remarks on Occasion of 200 Years' Anniversary of Its Adoption

ANDRZEJ DZIADZIO The Constitution of the Duchy of Warsaw 1807. Some remarks on occasion of 200 years’ anniversary of its adoption The great political vivacity accompaning the Four Years Seym (1788–1792), The Kościuszko’s Insurrection (1794) as well as the shock experienced by the nation with the loss of their statehood (1795) doubtless laid foundations for the moral rebirth of the Poles. In their consciousness there grew a belief in their inalienable right to have their own independent state. This feeling was deepened by the Partitioners’, and particularly Prussia’s, policy. In view of the fact that, following the partitions, the population of Poles living in the Prussian state was but slightly smaller than the population of Ger- mans, the Prussian government took the decision on the liquidation of the Polish sepa- ratedness in legal and national sense. As a result, Polish law was replaced by Landrecht of 1794. The language of local people was ignored, German being introduced in its place in civil service, judiciary and schools. The new administrative system struck a blow at the traditional forms of nobiliary self-government. In addition, the rigid fiscal policy of the Prussian government, while pursued with a disregard for Polish element, generated among the Poles unfriendly attitudes toward what was alien. Polish society, to a large extent permeated with a nobiliary ethos, understood that the restoring of their own statehood was necessary not only in order to maintain their cultural and linguistic identity, but also to guarantee their status of citizens having a share in the government of the country.