A Short History of Austerlitz, Tom Moreland, Town Historian [Excerpted, Without Endnotes, from the Old Houses of Austerlitz (AHS 2018)]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte's Invasion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London imesT Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia Julia Dittrich East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dittrich, Julia, "“We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1457. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia _______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Julia Dittrich August 2012 _______________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Napoleon Bonaparte, The London Times, English Identity ABSTRACT “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia by Julia Dittrich “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia aims to illustrate how The London Times interpreted and reported on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. -

Common and Noteworthy Instruments from 1750S-1800S' Eastern

Common and Noteworthy Instruments from 1750s-1800s’ Eastern USA Emory Jacobs Faculty Sponsor: Dr. Scott Marosek Department of Music During the 1700s and 1800s, residents of the eastern seaboard of North America enjoyed a wide variety of instruments, many of them built for “contrast and variety.”1 Availability, on the other hand, was a different story. While few accounts of the musical scene in that time period exist for more rural settings, records of the area and the events of the period from 1750 through the 1800s paint an interesting picture of how specific social classes and needs determined an instrument’s popularity. At the time, instruments were highly controversial, especially among specific religious groups.2 The religious restrictions on music occurred in relatively isolated sub- cultures in America, whereas notable sources from Germany would spend a novel’s worth of pages praising how perfect the organ was and would carefully list the detail of instruments’ tuning, mechanisms, and origins.3 When comparing these European instrument lists or collections with confirmed colonial instruments, one finds that very few of the elaborate, most prized instruments were exported to North America. Even outside America’s religious institutions, instruments were sometimes considered profane.4 While some instruments and some musical styles escaped such stigma, other instruments and styles had more ominous ties or were considered inelegant; the violin and fiddle offer one illustration.5 The phenomenon suggests that American society’s acceptance of music may have been a sensitive or subtle affair, as the difference between the violin and fiddle is often described as the fiddle being a poorly crafted violin or, in some cases, as a different musical style performed on the violin. -

Chapter 13: North and South, 1820-1860

North and South 1820–1860 Why It Matters At the same time that national spirit and pride were growing throughout the country, a strong sectional rivalry was also developing. Both North and South wanted to further their own economic and political interests. The Impact Today Differences still exist between the regions of the nation but are no longer as sharp. Mass communication and the migration of people from one region to another have lessened the differences. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 13 video, “Young People of the South,” describes what life was like for children in the South. 1826 1834 1837 1820 • The Last of • McCormick • Steel-tipped • U.S. population the Mohicans reaper patented plow invented reaches 10 million published Monroe J.Q. Adams Jackson Van Buren W.H. Harrison 1817–1825 1825–1829 1829–1837 1837–1841 1841 1820 1830 1840 1820 1825 • Antarctica • World’s first public discovered railroad opens in England 384 CHAPTER 13 North and South Compare-and-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you analyze the similarities and differences between the development of the North and the South. Step 1 Mark the midpoint of the side edge of a sheet of paper. Draw a mark at the midpoint. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold the outside edges in to touch at the midpoint. Step 3 Turn and label your foldable as shown. Northern Economy & People Economy & People Southern The Oliver Plantation by unknown artist During the mid-1800s, Reading and Writing As you read the chapter, collect and write information under the plantations in southern Louisiana were entire communities in themselves. -

A Chronology of Edwards' Life and Writings

A CHRONOLOGY OF EDWARDS’ LIFE AND WRITINGS Compiled by Kenneth P. Minkema This chronology of Edwards's life and times is based on the dating of his early writings established by Thomas A. Schafer, Wallace E. Anderson, and Wilson H. Kimnach, supplemented by volume introductions in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, by primary sources dating from Edwards' lifetime, and by secondary materials such as biographies. Attributed dates for literary productions indicate the earliest or approximate points at which Edwards probably started them. "Miscellanies" entries are listed approximately in numerical groupings by year rather than chronologically; for more exact dating and order, readers should consult relevant volumes in the Edwards Works. Entries not preceded by a month indicates that the event in question occurred sometime during the calendar year under which it listed. Lack of a pronoun in a chronology entry indicates that it regards Edwards. 1703 October 5: born at East Windsor, Connecticut 1710 January 9: Sarah Pierpont born at New Haven, Connecticut 1711 August-September: Father Timothy serves as chaplain in Queen Anne's War; returns home early due to illness 1712 March-May: Awakening at East Windsor; builds prayer booth in swamp 1714 August: Queen Anne dies; King George I crowned November 22: Rev. James Pierpont, Sarah Pierpont's father, dies 1716 September: begins undergraduate studies at Connecticut Collegiate School, Wethersfield 2 1718 February 17: travels from East Windsor to Wethersfield following school “vacancy” October: moves to -

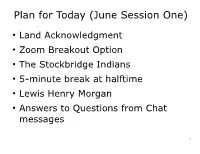

June Session One Presentation

Plan for Today (June Session One) ● Land Acknowledgment ● Zoom Breakout Option ● The Stockbridge Indians ● 5-minute break at halftime ● Lewis Henry Morgan ● Answers to Questions from Chat messages 1 “Part 2” Fridays in June Greater detail on Algonkian culture and values ● Less emphasis on history, more emphasis on values, many of which persist to the present day ● Stories and Myths – Possible Guest Appearance(s) – Joseph Campbell's The Power of Myth ● Current/Recent Fiction 2 “Part 3” Fall OLLI Course Deeper dive into philosophy ● Cross-pollination (Interplay of European values and customs with those of the Native Americans) ● Comparison of the Theories of Balance ● Impact of the Little Ice Age ● Enlightenment Philosophers' misapprehension of prelapsarian “Primitives” ● Lessons learned and Opportunities lost ● Dealing with climate change, income inequality, and intellectual property ● Steady State Economics; Mutual Aid; DIY-bio 3 (biohacking) and much more Sources for Today (in addition to the two books recommended) ● Grace Bidwell Wilcox (1891-1968) ● Richard Bidwell Wilcox “John Trusler's Conversations with the Wappinger Chiefs on Civilization” c. 1810 ● Patrick Frazier The Mohicans of Stockbridge ● Daniel Noah Moses The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan 4 5 Indigenous Cultures Part 2 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus ● People arrived in the Americas earlier than had been thought ● There were many more people in the Americas than in previous estimates ● American cultures were far more sophisticated -

HISTORY of MONTGOMERY COUNTY. Ments Extended From

'20 HISTORY OF MONTGOMERY COUNTY. ments extended from New Amsterdam (New York) on the south, to Albany on the north, mainly along the Hudson river, but there are well defined evidences of their early occupation of what is now western Ver- mont, and also part of Massachusetts; and at the same time they also advanced their outposts along the Mohawk valley toward the region of old Tryon county. CHAPTER III. The Indian Occupation — The Iroquois Confederacy,— The Five and Six Nations of Indians — Location and Names — Character and Power of the League — Social and Domestic Habits—The Mohawks — Treatment of the Jesuit Missionaries — Discourag- ing Efforts at Civilization—Names of Missionaries—Alliance with the English—Down- lall of the Confederacy. Q FTER the establishment of the Dutch in the New Netherlands the / \ region now embraced within the state of New York was held by three powers — one native and two foreign. The main colonies of the French (one of the powers referred to) were in the Canadas, but through the zeal of the Jesuit missionaries their line of possessions had been extended south and west of the St. Lawrence river, and some attempts at colonization had been made, but as yet with only partial success. In the southern and eastern portion of the province granted pom to the Duke of York were the English, who with steady yet sure ad- ual vances were pressing settlement and civilization westward and gradually nearing the French possessions. The French and English were at this time, and also for many years afterwards, conflicting powers, each study- ing for the mastery on both sides of the Atlantic; and with each suc- ceeding outbreak of war in the mother countries, so there were renewed hostilities between their American colonies. -

Medicine in 18Th and 19Th Century Britain, 1700-1900

Medicine in 18th and 19th century Britain, 1700‐1900 The breakthroughs th 1798: Edward Jenner – The development of How had society changed to make medical What was behind the 19 C breakthroughs? Changing ideas of causes breakthroughs possible? vaccinations Jenner trained by leading surgeon who taught The first major breakthrough came with Louis Pasteur’s germ theory which he published in 1861. His later students to observe carefully and carry out own Proved vaccination prevented people catching smallpox, experiments proved that bacteria (also known as microbes or germs) cause diseases. However, this did not put an end The changes described in the Renaissance were experiments instead of relying on knowledge in one of the great killer diseases. Based on observation and to all earlier ideas. Belief that bad air was to blame continued, which is not surprising given the conditions in many the result of rapid changes in society, but they did books – Jenner followed these methods. scientific experiment. However, did not understand what industrial towns. In addition, Pasteur’s theory was a very general one until scientists begun to identify the individual also build on changes and ideas from earlier caused smallpox all how vaccination worked. At first dad bacteria which cause particular diseases. So, while this was one of the two most important breakthroughs in ideas centuries. The flushing toilet important late 19th C invention wants opposition to making vaccination compulsory by law about what causes disease and illness it did not revolutionise medicine immediately. Scientists and doctors where the 1500s Renaissance – flushing system sent waste instantly down into – overtime saved many people’s lives and wiped‐out first to be convinced of this theory, but it took time for most people to understand it. -

Changes in Print Paper During the 19Th Century

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Charleston Library Conference Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century AJ Valente Paper Antiquities, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/charleston An indexed, print copy of the Proceedings is also available for purchase at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston. You may also be interested in the new series, Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences. Find out more at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston-insights-library-archival- and-information-sciences. AJ Valente, "Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century" (2010). Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284314836 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. CHANGES IN PRINT PAPER DURING THE 19TH CENTURY AJ Valente, ([email protected]), President, Paper Antiquities When the first paper mill in America, the Rittenhouse Mill, was built, Western European nations and city-states had been making paper from linen rags for nearly five hundred years. In a poem written about the Rittenhouse Mill in 1696 by John Holme it is said, “Kind friend, when they old shift is rent, Let it to the paper mill be sent.” Today we look back and can’t remember a time when paper wasn’t made from wood-pulp. Seems that somewhere along the way everything changed, and in that respect the 19th Century holds a unique place in history. The basic kinds of paper made during the 1800s were rag, straw, manila, and wood pulp. -

Daughters of the Nation: Stockbridge Mohican Women, Education

DAUGHTERS OF THE NATION: STOCKBRIDGE MOHICAN WOMEN, EDUCATION, AND CITIZENSHIP IN EARLY AMERICA, 1790-1840 by KALLIE M. KOSC Honors Bachelor of Arts, 2008 The University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, Texas Master of Arts, 2011 The University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, Texas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of AddRan College of Liberal Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 Copyright by Kallie M. Kosc 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to a great number of people, both personal and professional, who supported the completion of this project over the past five years. I would first like to acknowledge the work of Stockbridge-Munsee tribal historians who created and maintained the tribal archives at the Arvid E. Miller Library and Museum. Nathalee Kristiansen and Yvette Malone helped me navigate their database and offered instructive conversation during my visit. Tribal Councilman Jeremy Mohawk graciously instructed me in the basics of the Mohican language and assisted in the translation of some Mohican words and phrases. I have also greatly valued my conversations with Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Bonney Hartley whose tireless work to preserve her nation’s history and sacred sites I greatly admire. Numerous curators, archivists, and librarians have assisted me along the way. Sarah Horowitz and Mary Crauderueff at Haverford College’s Quaker and Special Collections helped me locate many documents central to this dissertation’s analysis. I owe a large debt to the Gest Fellowship program at the Quaker and Special Collections for funding my research trip to Philadelphia. -

Chapter 13: North and South, 1820-1860

North and South 1820–1860 Why It Matters At the same time that national spirit and pride were growing throughout the country, a strong sectional rivalry was also developing. Both North and South wanted to further their own economic and political interests. The Impact Today Differences still exist between the regions of the nation but are no longer as sharp. Mass communication and the migration of people from one region to another have lessened the differences. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 13 video, “Young People of the South,” describes what life was like for children in the South. 1826 1834 1837 1820 • The Last of • McCormick • Steel-tipped • U.S. population the Mohicans reaper patented plow invented reaches 10 million published Monroe J.Q. Adams Jackson Van Buren W.H. Harrison 1817–1825 1825–1829 1829–1837 1837–1841 1841 1820 1830 1840 1820 1825 • Antarctica • World’s first public discovered railroad opens in England 384 CHAPTER 13 North and South Compare-and-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you analyze the similarities and differences between the development of the North and the South. Step 1 Mark the midpoint of the side edge of a sheet of paper. Draw a mark at the midpoint. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold the outside edges in to touch at the midpoint. Step 3 Turn and label your foldable as shown. Northern Economy & People Economy & People Southern The Oliver Plantation by unknown artist During the mid-1800s, Reading and Writing As you read the chapter, collect and write information under the plantations in southern Louisiana were entire communities in themselves. -

Political Developments in Europe During the 19Th Century

Political Developments in Europe During the 19th Century TOPICS COVERED: -The Congress of Vienna -European nationalism -Changes to the Ottoman, Austrian, and Russian empires -The Unification of Italy -The Unification of Germany The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) • After Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, European heads of government were looking to establish long-lasting peace and stability on the continent. • The goal was collective security and stability for all of Europe. • A series of meetings known as the Congress of Vienna were called to set up policies to achieve this goal. This went on for 8 months. The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) • Most of the decisions were made among representatives of the five “great powers”- Russia, Prussia, Austria, Great Britain, and France. • By far the most influential representative was the foreign minister of Austria, Klemens von Metternich. • Metternich distrusted the democratic ideals of the French Revolution and had 3 primary goals: 1. Prevent future French aggression by surrounding France with strong countries. 2. Restore a balance of power so that no country would be a threat to others. 3. Restore Europe’s traditional royal families to the thrones they held before Napoleon’s conquests. The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) Results of the Congress of Vienna: • France’s neighboring countries were strengthened (ex: 39 German states were loosely joined to create the German Confederation; the former Austrian Netherlands and Dutch Netherlands were united to form the Kingdom of the Netherlands) • Ruling families of France, Spain, and several states in Italy and Central Europe regained their thrones (it was believed this would stabilize relations among European nations) The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) Although France had been the aggressor under Napoleon, it was not severely punished at the Congress of Vienna. -

Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE December 2015 Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Judd David Olshan Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Olshan, Judd David, "Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 399. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/399 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract: Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Historians follow those tributaries of early American history and trace their converging currents as best they may in an immeasurable river of human experience. The Butlers were part of those British imperial currents that washed over mid Atlantic America for the better part of the eighteenth century. In particular their experience reinforces those studies that recognize the impact that the Anglo-Irish experience had on the British Imperial ethos in America. Understanding this ethos is as crucial to understanding early America as is the Calvinist ethos of the Massachusetts Puritan or the Republican ethos of English Wiggery. We don't merely suppose the Butlers are part of this tradition because their story begins with Walter Butler, a British soldier of the Imperial Wars in America.