Common and Noteworthy Instruments from 1750S-1800S' Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte's Invasion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London imesT Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia Julia Dittrich East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dittrich, Julia, "“We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1457. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia _______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Julia Dittrich August 2012 _______________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Napoleon Bonaparte, The London Times, English Identity ABSTRACT “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia by Julia Dittrich “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia aims to illustrate how The London Times interpreted and reported on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Chapter 13: North and South, 1820-1860

North and South 1820–1860 Why It Matters At the same time that national spirit and pride were growing throughout the country, a strong sectional rivalry was also developing. Both North and South wanted to further their own economic and political interests. The Impact Today Differences still exist between the regions of the nation but are no longer as sharp. Mass communication and the migration of people from one region to another have lessened the differences. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 13 video, “Young People of the South,” describes what life was like for children in the South. 1826 1834 1837 1820 • The Last of • McCormick • Steel-tipped • U.S. population the Mohicans reaper patented plow invented reaches 10 million published Monroe J.Q. Adams Jackson Van Buren W.H. Harrison 1817–1825 1825–1829 1829–1837 1837–1841 1841 1820 1830 1840 1820 1825 • Antarctica • World’s first public discovered railroad opens in England 384 CHAPTER 13 North and South Compare-and-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you analyze the similarities and differences between the development of the North and the South. Step 1 Mark the midpoint of the side edge of a sheet of paper. Draw a mark at the midpoint. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold the outside edges in to touch at the midpoint. Step 3 Turn and label your foldable as shown. Northern Economy & People Economy & People Southern The Oliver Plantation by unknown artist During the mid-1800s, Reading and Writing As you read the chapter, collect and write information under the plantations in southern Louisiana were entire communities in themselves. -

Sala Margolín, El Cierre De Un Espacio Emblemático

Revista de la Academia de Música del Palacio de Minería • Otoño de 2012 Número 6 Sala Margolín, el cierre de un espacio emblemático Fotos de la Testimonios, recuerdos, evocaciones Temporada La Cuarta Sinfonía 2012 de Sibelius El arte musical de Arturo Márquez Una semblanza de Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau Entrevista con cuatro músicos de la Orquesta Sinfónica de Minería 1 pág. El cierre de la emblemática Sala Margolín, por Arturo Soní Cassani. Imágenes proporcionadas por Luis Pérez Santoja. Testimonios de Lucrecia Arcos. El arte musical de Arturo Márquez, por Theo Hernández. Entrevista con cuatro músicos de la OSM: Janet Paulus, arpista (principal); Pastor Solís, Segundo Violín (principal), Francisca Ettlin, corno inglés (principal) y Manuel Hernández, contrafagot (principal),por Fernando Fernández. Imágenes de los conciertos de la Temporada 2012 de la Orquesta Sinfónica de Minería, por Lorena Alcaraz. Una semblanza de Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, por Mario Saavedra. Un soneto de Leopoldo Lugones sobre Juventino Rosas, por Fernando Fernández. Entrevista con François Weigel, piano, y Thomas Bloch, Ondas Martenot, sobre Olivier Messiaen, por Sergio Vela. La Cuarta Sinfonía de Sibelius, por Juan Arturo Brennan. El instrumento invitado, El violonchelo, por Miguel Zenker. De Kurt Weill al narcocorrido, por Jacobo Dayán. Entrevista con Sarita Hernández, bibliotecaria de la OSM. Recomendaciones discográficas por Jorge Terrazas y de Allende. Una estrella en ascenso, por Gilberto Suárez. Calendario del programa La ópera en el tiempo de Sergio Vela en Opus 94.5 de FM. Humor. Violas. Cartón de Ros. Noticias, por Gilberto Suárez Baz. 1 Hace unos cuantos meses se corrió por última vez la reja que daba acceso a Sala Margolín, un oasis cultural en Córdoba 100 (casi esquina con Álvaro Obregón) en la colonia Roma de la Ciudad de México. -

Bach & Baroque Virtuosity

Byron Schenkman Friends dec Bach & 27 Baroque Virtuosity Rachell Ellen Wong u violin Andrew Gonzalez u violoncello da spalla Byron Schenkman u harpsichord Antonio Vivaldi u 1678 - 1741 Sonata in B-flat Major, RV 47 Largo Allegro Largo Allegro Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre u 1665 - 1729 Suite no. 2 in G Minor Prélude Allemande Courante Courante Sarabande Gigue Gigue Menuet Jean Marie Leclair u 1697 - 1764 Ciaccona from the Sonata in G, op. 5, no. 12 Johann Sebastian Bach u 1685 - 1750 Partita in D Minor, BWV 1004 Allemanda Corrente Sarabanda Giga Ciaccona Thomas Balzar u 1630 – 1663 & Davis Mell u 1604 – 1662 Divisions on “John Come Kiss Me Now” Byron Schenkman Friends 8th Season u 3rd Concert u Bach & Baroque Virtuosity www.byronandfriends.org notes on the program By Byron Schenkman Johann Sebastian Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for As the violin became increasingly fashionable in early unaccompanied violin are large scale works which 18th-century France, French virtuosi such as Jean- transcend the possibilities one would expect from a Marie Leclair brought a distinctly French flavor to the small instrument with just four strings and a bow. In Italian sonata form. Like many of the great French writing these masterworks Bach drew on diverse styles violinists, Leclair was also a dance master and the for inspiration, including music by contemporary ciaccona which concludes his Sonata in G Major, op. Italian violinists and French harpsichordists. 5, no. 12, is a joyful tribute to the dance. While the violin and the harpsichord are well known J. S. Bach’s Partita in D Minor begins with the four instruments of the Baroque era, the violoncello da standard movements of a French suite and concludes spalla (cello of the shoulder) is an unusual Baroque with a ciaccona of monumental proportions. -

Medicine in 18Th and 19Th Century Britain, 1700-1900

Medicine in 18th and 19th century Britain, 1700‐1900 The breakthroughs th 1798: Edward Jenner – The development of How had society changed to make medical What was behind the 19 C breakthroughs? Changing ideas of causes breakthroughs possible? vaccinations Jenner trained by leading surgeon who taught The first major breakthrough came with Louis Pasteur’s germ theory which he published in 1861. His later students to observe carefully and carry out own Proved vaccination prevented people catching smallpox, experiments proved that bacteria (also known as microbes or germs) cause diseases. However, this did not put an end The changes described in the Renaissance were experiments instead of relying on knowledge in one of the great killer diseases. Based on observation and to all earlier ideas. Belief that bad air was to blame continued, which is not surprising given the conditions in many the result of rapid changes in society, but they did books – Jenner followed these methods. scientific experiment. However, did not understand what industrial towns. In addition, Pasteur’s theory was a very general one until scientists begun to identify the individual also build on changes and ideas from earlier caused smallpox all how vaccination worked. At first dad bacteria which cause particular diseases. So, while this was one of the two most important breakthroughs in ideas centuries. The flushing toilet important late 19th C invention wants opposition to making vaccination compulsory by law about what causes disease and illness it did not revolutionise medicine immediately. Scientists and doctors where the 1500s Renaissance – flushing system sent waste instantly down into – overtime saved many people’s lives and wiped‐out first to be convinced of this theory, but it took time for most people to understand it. -

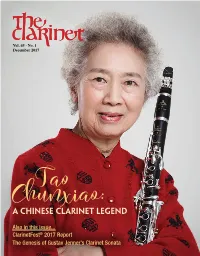

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

New France (Ca

New France (ca. 1600-1770) Trade silver, beaver, eighteenth century Manufactured in Europe and North America for trade with the Native peoples, trade silver came in many forms, including ear bobs, rings, brooches, gorgets, pendants, and animal shapes. According to Adam Shortt,5 the great France, double tournois, 1610 Canadian economic historian, the first regular Originally valued at 2 deniers, the system of exchange in Canada involving Europeans copper “double tournois” was shipped to New France in large quantities during occurred in Tadoussac in the early seventeenth the early 1600s to meet the colony’s century. Here, French traders bartered each year need for low-denomination coins. with the Montagnais people (also known as the Innu), trading weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco for animal pelts, especially those of the beaver. Because of the risks associated with In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded transporting gold and silver (specie) across the the first colonial settlement at Quebec on the Atlantic, and to attract and retain fresh supplies of St. Lawrence River. The one universally accepted coin, coins were given a higher value in the French medium of exchange in the infant colony naturally colonies in Canada than in France. In 1664, became the beaver pelt, although wheat and moose this premium was set at one-eighth but was skins were also employed as legal tender. As the subsequently increased. In 1680, monnoye du pays colony expanded, and its economic and financial was given a value one-third higher than monnoye needs became more complex, coins from France de France, a valuation that held until 1717 when the came to be widely used. -

Changes in Print Paper During the 19Th Century

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Charleston Library Conference Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century AJ Valente Paper Antiquities, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/charleston An indexed, print copy of the Proceedings is also available for purchase at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston. You may also be interested in the new series, Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences. Find out more at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston-insights-library-archival- and-information-sciences. AJ Valente, "Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century" (2010). Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284314836 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. CHANGES IN PRINT PAPER DURING THE 19TH CENTURY AJ Valente, ([email protected]), President, Paper Antiquities When the first paper mill in America, the Rittenhouse Mill, was built, Western European nations and city-states had been making paper from linen rags for nearly five hundred years. In a poem written about the Rittenhouse Mill in 1696 by John Holme it is said, “Kind friend, when they old shift is rent, Let it to the paper mill be sent.” Today we look back and can’t remember a time when paper wasn’t made from wood-pulp. Seems that somewhere along the way everything changed, and in that respect the 19th Century holds a unique place in history. The basic kinds of paper made during the 1800s were rag, straw, manila, and wood pulp. -

A History of Mandolin Construction

1 - Mandolin History Chapter 1 - A History of Mandolin Construction here is a considerable amount written about the history of the mandolin, but littleT that looks at the way the instrument e marvellous has been built, rather than how it has been 16 string ullinger played, across the 300 years or so of its mandolin from 1925 existence. photo courtesy of ose interested in the classical mandolin ony ingham, ondon have tended to concentrate on the European bowlback mandolin with scant regard to the past century of American carved instruments. Similarly many American writers don’t pay great attention to anything that happened before Orville Gibson, so this introductory chapter is an attempt to give equal weight to developments on both sides of the Atlantic and to see the story of the mandolin as one of continuing evolution with the odd revolutionary change along the way. e history of the mandolin is not of a straightforward, lineal development, but one which intertwines with the stories of guitars, lutes and other stringed instruments over the past 1000 years. e formal, musicological definition of a (usually called the Neapolitan mandolin); mandolin is that of a chordophone of the instruments with a flat soundboard and short-necked lute family with four double back (sometimes known as a Portuguese courses of metal strings tuned g’-d’-a”-e”. style); and those with a carved soundboard ese are fixed to the end of the body using and back as developed by the Gibson a floating bridge and with a string length of company a century ago. -

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY German Immigration to Mainland

The Flow and the Composition of German Immigration to Philadelphia, 1727-177 5 IGHTEENTH-CENTURY German immigration to mainland British America was the only large influx of free white political E aliens unfamiliar with the English language.1 The German settlers arrived relatively late in the colonial period, long after the diversity of seventeenth-century mainland settlements had coalesced into British dominance. Despite its singularity, German migration has remained a relatively unexplored topic, and the sources for such inquiry have not been adequately surveyed and analyzed. Like other pre-Revolutionary migrations, German immigration af- fected some colonies more than others. Settlement projects in New England and Nova Scotia created clusters of Germans in these places, as did the residue of early though unfortunate German settlement in New York. Many Germans went directly or indirectly to the Carolinas. While backcountry counties of Maryland and Virginia acquired sub- stantial German populations in the colonial era, most of these people had entered through Pennsylvania and then moved south.2 Clearly 1 'German' is used here synonymously with German-speaking and 'Germany' refers primar- ily to that part of southwestern Germany from which most pre-Revolutionary German-speaking immigrants came—Cologne to the Swiss Cantons south of Basel 2 The literature on German immigration to the American colonies is neither well defined nor easily accessible, rather, pertinent materials have to be culled from a large number of often obscure publications -

The Renaissance Cittern

The Renaissance Cittern Lord Aaron Drummond, OW [email protected] 1. HISTORY,DEVELOPMENT, CONSTRUC- while chromatic citterns are more associated with Italian TION and English music. [3] As far as the body of the instrument goes, citoles and ear- The Renaissance cittern most likely developed from the lier citterns had the back, ribs and neck carved from a single medieval citole. The citole was a small, flat-backed instru- block of wood with the soundboard and fingerboard being ment with four strings. It was usually depicted as having added. Later citterns were constructed from a flat back, frets and being plucked with a quill or plectrum. The citole bent ribs and separately carved neck, which cut down on in turn may have developed from a kind of ancient lyre called the materials cost. [10] Constructed citterns differ in con- a kithara by adding a fingerboard and then gradually remov- struction from lutes in that in citterns the back is made ing the (now redundant) arms. [1] The cittern may have been from a single flat piece of wood, whereas the lute has a large viewed as a revival of the ancient Greek instrument despite number (typically ten or more) of ribs which must be sep- being quite different in form. The word kithara also evolved arately bent and joined to the achieve the \bowl" shape. into the modern word guitar. This made lutes substantially more difficult to build as well Some modern instruments such as the German waldzither as more delicate than the cittern. Internally there are braces (literally `forest-cittern') and various Iberian instruments to strengthen the back and the soundboard, but like the lute, (Portuguese guitar, bandurria, etc) claim some descent from guitar, viol, etc there is no soundpost or bass bar.