The Khasi States and Shillong Municipality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Scott in North-East India 1802-1831

'Its interesting situation between Hindoostan and China, two names with which the civilized world has been long familiar, whilst itself remains nearly unknown, is a striking fact and leaves nothing to be wished, but the means and opportunity for exploring it.' Surveyor-General Blacker to Lord Amherst about Assam, 22 April, 1824. DAVID SCOTT IN NORTH-EAST INDIA 1802-1831 A STUDY IN BRITISH PATERNALISM br NIRODE K. BAROOAH MUNSHIRAM MANOHARLAL, NEW DELHI TO THE MEMORY OF DR. LALIT KUMAR BAROOAH PREFACE IN THE long roll of the East India Company's Bengal civil servants, placed in the North-East Frontier region. the name of David Scott stands out, undoubtably,. - as one of the most fasci- nating. He served the Company in the various capacities on the northern and eastern frontiers of the Bengal Presidency from 1804 to 1831. First coming into prominrnce by his handling of relations with Bhutan, Sikkim, and Tibet during the Nepal war of 1814, Scott was successively concerned with the Garo hills, the Khasi and Jaintia hills and the Brahma- putra valley (along with its eastern frontier) as gent to the Governor-General on the North-East Frontier of Bengal and as Commissioner of Assam. His career in India, where he also died in harness in 1831, at the early age of forty-five, is the subject of this study. The dominant feature in his ideas of administration was Paternalism and hence the sub-title-the justification of which is fully given in the first chapter of the book (along with the importance and need of such a study). -

Meghalaya Receives Agriculture Award Meghalaya Receives

March, 2018 MEGNEWS MEGNEWSMONTHTLY NEWS BULLETIN A PUBLICATION OF THE DIRECTORATE OF INFORMATION & PUBLIC RELATIONS, MEGHALAYA TOLL - FREE DATE: March 29, 2018 FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION ISSUE NO. 104 NO. - 1800-345-3644 CM attends Natural CM attends International CM urges Youth to Workshop on Continuing Two-Day Mega Health Swearing - in Ceremony On the Lighter Side Resource Management Inter-Disciplinary Seminar look for opportunities Professional Development Mela Concludes of New CM and Cabinet and Climate Change Meet beyond State at Regional of Counsellors Ministers at Tura 2 3 Colloquium 4 5 6 7 8 Meghalaya Receives Agriculture award Prime Minister, Shri. Narendra Modi on 17th March 2018 awarded Meghalaya an award, which was possible because of the hard work of the farmers and the for its growth in the agriculture sector. Chief Minister of Meghalaya, Shri. officials of the Department of Agriculture and other stakeholders. Shri. Modi Conrad K. Sangma received the award on behalf of the people of the State in handed over the award to the Chief Minister during the Krishi Unnati Mela presence of Agriculture Minister, Shri. Banteidor Lyngdoh. held at India Agriculture Research Institute Mela Groud at Pusa in New Delhi. Addressing the gathering, the Prime Minister said that such Unnati Melas The Chief Minister has dedicated the award to the people of the State especially play a key role in paving the way for New India. He said that today, he has farmers. “It gives an immense pleasure that I have received the award on behalf the opportunity to simultaneously speak to two sentinels of New India – of the farmers of the State, who have scripted a success story. -

Polities and Ethnicities in North-East India Philippe Ramirez

Margins and borders: polities and ethnicities in North-East India Philippe Ramirez To cite this version: Philippe Ramirez. Margins and borders: polities and ethnicities in North-East India. Joëlle Smadja. Territorial Changes and Territorial Restructurings in the Himalayas, Adroit, 2013, 978-8187393016. hal-01382599 HAL Id: hal-01382599 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01382599 Submitted on 17 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Margins and borders: polities and ethnicities in North-East India1 Philippe RAMIREZ in Joëlle Smadja (ed.) Territorial Changes and Territorial Restructurings in the Himalayas. Delhi, 2013 under press. FINAL DRAFT, not to be quoted. Both the affirmative action policies of the Indian State and the demands of ethno- nationalist movements contribute to the ethnicization of territories, a process which began in colonial times. The division on an ethnic basis of the former province of Assam into States and Autonomous Districts2 has multiplied the internal borders and radically redefined the political balance between local communities. Indeed, cultural norms have been and are being imposed on these new territories for the sake of the inseparability of identity, culture and ancestral realms. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

Critically Assessing Traditions: the Case of Meghalaya

Working Paper no.52 CRITICALLY ASSESSING TRADITIONS: THE CASE OF MEGHALAYA Manorama Sharma NEIDS (Shillong, India) November 2004 Copyright © Manorama Sharma, 2004 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Development Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. 1 Crisis States Programme Critically Assessing Traditions: The Case of Meghalaya1 Manorama Sharma NEIDS (Shillong, India) It could be cogently argued ...that in Meghalaya, there are not two but three competing systems of authority – each of which is seeking to ‘serve’ or represent the same constituency. The result has been confusion and confrontation especially at the local level on a number of issues.2 This observation by the experts of the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution reflects the present crisis of governance in the North East Indian state of Meghalaya. In fact, the main tussle for power and control over resources seems to be between the tribal organisations that have been designated by the Constitution of India as ‘traditional institutions’, and the constitutionally elected bodies. -

Urban Development

MMEGHALAYAEGHALAYA SSTATETATE DEVELOPMENTDEVELOPMENT RREPORTEPORT CHAPTER VIII URBAN DEVELOPMENT 8.1. Introducti on Urbanizati on in Meghalaya has maintained a steady growth. As per 2001 Census, the state has only 19.58% urban populati on, which is much lower than the nati onal average of 28%. Majority of people of the State conti nue to live in the rural areas and the same has also been highlighted in the previous chapter. As the urban scenario is a refl ecti on of the level of industrializati on, commercializati on, increase in producti vity, employment generati on, other infrastructure development of any state, this clearly refl ects that the economic development in the state as a whole has been rather poor. Though urbanizati on poses many challenges to the city dwellers and administrators, there is no denying the fact that the process of urbanizati on not only brings economic prosperity but also sets the way for a bett er quality of life. Urban areas are the nerve centres of growth and development and are important to their regions in more than one way. The current secti on presents an overview of the urban scenario of the state. 88.2..2. UUrbanrban sseett llementement andand iitsts ggrowthrowth iinn tthehe sstatetate Presently the State has 16 (sixteen) urban centres, predominant being the Shillong Urban Agglomerati on (UA). The Shillong Urban Agglomerati on comprises of 7(seven) towns viz. Shillong Municipality, Shillong Cantonment and fi ve census towns of Mawlai, Nongthymmai, Pynthorumkhrah, Madanrti ng and Nongmynsong with the administrati on vested in a Municipal Board and a Cantonment Board in case of Shillong municipal and Shillong cantonment areas and Town Dorbars or local traditi onal Dorbars in case of the other towns of the agglomerati on. -

Working Through Partition: Making a Living in the Bengal Borderlandsã

IRSH 46 (2001), pp. 393±421 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859001000256 # 2001 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Working Through Partition: Making a Living in the Bengal Borderlandsà Willem van Schendel Summary: Partition, the break-up of colonial India in 1947, has been the subject of considerable serious historical research, but almost exclusively from two distinctive perspectives: as a macropolitical event; or as a cultural and personal disaster. Remarkably, very little is known about the socioeconomic impact of Partition on different localities and individuals. This exploratory essay considers how Partition affected working people's livelihood and labour relations. The essay focuses on the northeastern part of the subcontinent, where Partition created an international border separating East Bengal ± which became East Pakistan, then Bangladesh ± from West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, and other regions which joined the new state of India. Based largely on evidence contained in ``low-level'' state records, the author explores how labour relations for several categories of workers in the new borderland changed during the period of the late 1940s and 1950s. In the Indian subcontinent, the word ``Partition'' conjures up a particular landscape of knowledge and emotion. The break-up of colonial India has been presented from vantage points which privilege certain vistas of the postcolonial landscape. The high politics of the break-up itself, the violence and major population movements, and the long shadows which Partition cast over the relationship between India and Pakistan (and, from 1971, Bangladesh) have been topics of much myth-making, intense polemics, and considerable serious historical research. As three rival nationalisms were being built on con¯icting interpretations of Partition, most analysts and historians have been drawn towards the study of Partition as a macropolitical event. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

Language Recognition and Identity Formation in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Special Conference Issue (Vol. 12, No. 5, 2020. 1-6) from 1st Rupkatha International Open Conference on Recent Advances in Interdisciplinary Humanities (rioc.rupkatha.com) Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n5/rioc1s17n2.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s17n2 Language Recognition and Identity Formation in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills Mereleen Lily Lyngdoh Y. Blah Assistant Professor, Dyal Singh College, University of Delhi, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The official use of any language by the administration and employment of the said language by the state whether through educational institutions and administrators as a standard literary dialect, gives it recognition. The Education policy adopted by the British and the choice of English being made the language of instruction throughout the country is made evident in Macaulay’s Minute of 1835 and is reiterated again more than a decade later in the Minute of 1847. From the very beginning English was associated with the administration and the benefits that it would bring but they failed to take into account the people who were unfamiliar with it. The categorization and later association of languages with religion, caste, community, tribe and class is evident in the various census undertakings as the official recognition became a determination of its status. In the Census of 1891, the Khasis and Jaintias are relegated as “two groups statistically insignificant”, considering the population and the number of people who spoke the languages associated with the communities. -

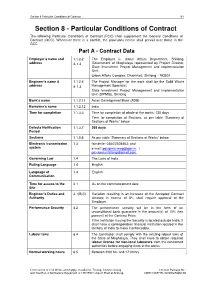

Nerccdiptr- 02Shgswm-08-Section-8

Section 8 Particular Conditions of Contract 8-1 Section 8 - Particular Conditions of Contract The following Particular Conditions of Contract (PCC) shall supplement the General Conditions of Contract (GCC). Whenever there is a conflict, the provisions herein shall prevail over those in the GCC. Part A - Contract Data Employer’s name and 1.1.2.2 The Employer is: Urban Affairs Department, Shillong, address & 1.3 Government of Meghalaya represented by Project Director, State Investment Project Management and Implementation Unit, Urban Affairs Complex, Dhankheti, Shillong - 793001 Engineer’s name & 1.1.2.4 The Project Manager for the work shall be the Solid Waste address & 1.3 Management Specialist State Investment Project Management and Implementation Unit (SIPMIU), Shillong Bank’s name 1.1.2.11 Asian Development Bank (ADB) Borrower’s name 1.1.2.12 India Time for completion 1.1.3.3 Time for completion of whole of the works: 730 days Time for completion of Sections: as per table “Summary of Sections of Works” below Defects Notification 1.1.3.7 365 days Period Sections 1.1.5.6 As per table “Summary of Sections of Works” below Electronic transmission 1.3 facsimile: 0364/2505463; and system e-mail: [email protected]. / [email protected]. Governing Law 1.4 The Laws of India Ruling Language 1.4 English Language of 1.4 English Communication Time for access to the 2.1 As on the commencement date. Site Engineer’s Duties and 3.1(B)(ii) Variation resulting in an increase of the Accepted Contract Authority Amount in excess of 5% shall require approval of the Employer. -

Study on Areas Affected by Mining in Meghalaya by NEHU-MBMA

Technical Report of Project entitled Study on Mining Affected Areas and its Impact on Livelihood Meghalaya- Community Led Landscape Management Project Meghalaya Basin Management Agency Shillong 2019 Prof. O. P. Singh Principal Investigator/Consultant Department of Environmental Studies North-Eastern Hill University Shillong- 793022 Meghalaya Project Number: P 157836 Contract Number: MBMA/CLLMP/PP/Mining/46/2017 Preface The indiscriminate and unscientific mining and absence of post mining treatment and management of mined areas have made the fragile ecosystems of Meghalaya more vulnerable to environmental degradation and depletion of natural resources. As a consequence, the natural resources such as soil, water, forest and forest products, biodiversity etc. have been severely affected both in terms of their quality and quantity in the mining areas of the state. The traditional livelihood options linked to these resources have also been found affected. The information on effects of coal, limestone, sand mining etc. on land, water, forest resources and the community are fragmentary and thus needed consolidation with recent data. The meagre information available on the effect of mining on human health, natural resources with special emphasis on soil, water and biodiversity, livelihood of the people with particular reference to agriculture including horticulture, livestock, aquaculture and fishery are scattered, hence needed compilation. Such information is essential to strengthen the community led natural resource management practices in order to facilitate community led planning coupled with technical inputs and funding broadly in the areas of forest, water and soil in Meghalaya. Hence, the need was felt to compile available information in order to identify the drivers of degradation and also for promoting activities towards conservation of forest, soil and water resources with reference to sustainable livelihood. -

ORDER 1. Entry of Tourists from Outside the State Shall Not Be

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA HOME (POLITICAL) DEPARTMENT No. POL.75/2020/Pti/100 Dated, Shillong the 28" May, 2021 ORDER Whereas, it is observed that the number of COVID-19 cases in the State continues to rise sharply and hospital bed occupancy is nearing saturation; Therefore, in supersession to all orders issued in respect of Containment Measures in the State, the following shall be enforced in the State w.e.f. 318t May, 2021 until further orders. Entire State: 1. Political, public, social and religious gatherings are not permitted including conferences, meetings and trainings Entry of tourists from outside the State shall not be permitted and all tourist spots shall remain closed. Sports activities are not permitted. Inter-State movement of persons shall be restricted. This shall not apply for transit vehicles of Assam / Tripura / Manipur / Mizoram. 5. International Border Trade shall be regulated by the Deputy Commissioners. East Khasi Hills District: 6. Lockdown shall be extended in East Khasi Hills District till 5:00 AM of 7'" June, 2021. 7. The Deputy Commissioner, East Khasi Hills District shall make suitable arrangements for availability of essential commodities in the localities on need basis. 8. Home Delivery Services are permitted subject to prior permission and regulation by the Deputy Commissioner, East Khasi Hills District. 9. Inter-district movement of persons from and to East Khasi Hills District shall be restricted. 10. All Central Government offices other than those notified by Home (Political) Department vide Notification No. POL.117/2020/Pt.1I/136, dated 28-05-2021 shall remain closed. 11. All State Government offices other than those notified by Personnel & A.R (A) Department vide Notification No.