The Atlas End to End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initiation Au Maroc

INITIATION AU MAROC INSTITUT DES HAUTES ÉTUDES MAROCAINES INITIATION AU MAROC Nouvelle édition mise à jour VANOEST LES EDITIONS D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE I)i\ R 1 S MCMXLV OAT COLLABORÉ A CET OUVRAGE : 1 MM. É. LÉVI-PROVENÇAL, directeur honoraire de l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines, professeur à la Faculté des Lettres d'Alger. J. CÉLÉRIER, directeur d'études de géographie à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. G. S. COLIN, directeur d'études de linguistique nord-afri- caine à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines, pro- fesseur à l'École des Langues orientales. L EMBERGER, ancien chef du service botanique à l'Institut Scientifique Chérifien, professeur à la Faculté des Sciences de Montpellier. E. LAOUST, directeur d'études honoraire de dialectes berbè- res à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. Le docteur H.-P.-J. RENAUD, directeur d'études d'histoire des sciences à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. HENRI TERRASSE, directeur de l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines, correspondant de l'Institut. II MM. RENÉ HOFFHERR, maître des requêtes au Conseil d'État, an- cien directeur des Centres d'études juridiques et admi- nistratives \à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. PAUL MAUCHAUSSÉ, MARCEL BOUSSER et JACQUES MTLLERON, maîtres de conférences aux Centres d'études juridi- ques et administratives. HENRI MAZOYER, contrôleur civil, CLAUDE ECORCHEVILLE, J. PLASSE et JEAN FINES, contrôleurs civils adjoints. J. VALLET, Chef du Bureau de documentation économique au Service du Commerce. AVANT-PROPOS DE LA PREMIÈRE ÉDITION (1932) Jusqu'à une date récente, le Français qui arrivait au Ma- roc recevait un choc : du premier coup, une impression puissante d'étrangeté, de dépaysement le saisissait. -

Moroccan Climbing: Rock, Sun and Snow

PAUL KNOTT Moroccan Climbing: Rock, Sun and Snow OroCCO fascinates me. It has a rich complexity, retaining an alluring M mystique despite being well travelled and documented. During 1998 and 1999 I was lucky enough to get a real insight into the country and its climbing through a post at the delightful Al Akhawayn University in the Middle Atlas Mountains. Here I give a flavour of the rock climbing, skiing and mountain walking, all of them spiced with the cultural interest inherent in Morocco's mountain country. After three days' driving from the UK, I sped through dry limestone plateaux to Ifrane with its promise of sunshine and snow. I found myself sharing an office with Michael Peyron - Alpine Club member, Atlas guidebook author and Berber expert. Along with other companions, we escaped at weekends to explore the wealth of lesser-known mountains a short drive from the fairy-tale campus. We sought and found crags and mountains with European-style ease of access. For big, unexplored rock climbs one of my favourite places was the Dades Gorge. This was visited by Trevor Jones and Les Brown in 1990, but otherwise seems to have seen little or no climbing. Above Boumalne-de Dades the valley becomes strikingly beautiful, with its kasbahs and its unusual rock features (doigts de singes or monkey fingers) set amongst emerald green jardins. On my first visit we got no further than this; the downpour sent raging torrents across the road and stranded us at Ait-Arbi. We found the doigts disappointing for climbing. I returned some weeks later, to the gorge itself. -

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

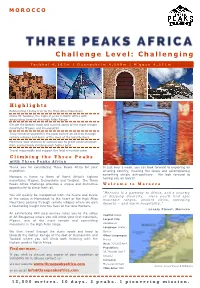

Challenge Level: Challenging

MOROCCO Challenge Level: Challenging Toubkal 4,167m | O u a n o u k r i m 4 , 0 8 9 m | M ’ g o u n 4 , 0 7 1 m H i g h l i g h t s Exhilarating 10 day trek to the High Atlas Mountains Climb Mt Toubkal, the highest peak in North Africa with astounding views of the High Atlas Range Get off the beaten track and summit some of the most remote mountains M’goun and Ouanoukrim Truly immerse yourself in the local culture as we trek through remote villages and learn of the lives of the local Berbers Maximise your chances of success due to great acclimatisation from successively climbing each higher peak Travel responsibly and support the local mountain crew Climbing the Three Peaks with Three Peaks Africa Thank you for considering Three Peaks Africa for your In just over a week, you can look forward to exploring an expedition. amazing country, meeting the locals and accomplishing something simply extraordinary. We look forward to Morocco is home to three of North Africa’s highest having you on board! mountains; M’goun, Ouanoukrim and Toubkal. The Three Peaks Africa Challenge provides a unique and distinctive Welcome to Morocco opportunity to climb them all. “Morocco is a gateway to Afr ica, and a country You will quickly be transported from the hustle and bustle of d iz zy ing d ivers ity . Here you’ ll f ind ep ic of the souks in Marrakech to the heart of the High Atlas mountain ranges, anc ie nt c ities, sweeping Mountains passing through remote villages where we gain deserts – and warm hospitality .” a fascinating insight into the lives of the local Berbers. -

Quaternary Glaciations of the Atlas Mountains, North Africa

The University of Manchester Research Quaternary Glaciations of the Atlas Mountains, North Africa DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00076-3 Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Hughes, P. D., Fenton, C. R., & Gibbard, P. L. (2011). Quaternary Glaciations of the Atlas Mountains, North Africa. In Developments in Quaternary Science|Dev. Quat. Sci. (Vol. 15, pp. 1065-1074). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00076-3 Published in: Developments in Quaternary Science|Dev. Quat. Sci. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:03. Oct. 2021 Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This chapter was originally published in the book Developments in Quaternary Science, Vol.15, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non- commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who know you, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. -

Reasonable Plans. the Story of the Kasbah Du Toubkal

The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal MARRAKECH • MOROCCO DEREK WORKMAN The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal Marrakech • Morocco Derek WorkMan Second edition (2014) The information in this booklet can be used copyright free (without editorial changes) with a credit given to the Kasbah du Toubkal and/or Discover Ltd. For permission to make editorial changes please contact the Kasbah du Toubkal at [email protected], or tel. +44 (0)1883 744 392. Discover Ltd, Timbers, Oxted Road, Godstone, Surrey, RH9 8AD Photography: Alan Keohane, Derek Workman, Bonnie Riehl and others Book design/layout: Alison Rayner We are pleased to be a founding member of the prestigious National Geographic network Dedication Dreams are only the plans of the reasonable – dreamt by Discover realised by Omar and the Worker of Imlil (Inscription on a brass plaque at the entrance to the Kasbah du Toubkal) his booklet is dedicated to the people of Imlil, and to all those who Thelped bring the ‘reasonable plans’ to reality, whether through direct involvement with Discover Ltd. and the Kasbah du Toubkal, or by simply offering what they could along the way. Long may they continue to do so. And of course to all our guests who contribute through the five percent levy that makes our work in the community possible. CONTENTS IntroDuctIon .........................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1 • The House on the Hill .......................................13 CHAPTER 2 • Taking Care of Business .................................29 CHAPTER 3 • one hand clapping .............................................47 CHAPTER 4 • An Association of Ideas ...................................57 CHAPTER 5 • The Work of Education For All ....................77 CHAPTER 6 • By Bike Through the High Atlas Mountains .......................................99 CHAPTER 7 • So Where Do We Go From Here? .......... -

Climbing in the Atlas Mountains a Survey

HAMISH BROWN Climbing in the Atlas Mountains A Survey (Plates 24-27) magine a country with eighty per cent sunshine throughout the year, I grand mountain scenery, its rock climbing potential barely touched, all within easy reach, with no political hassles orcostly fees, and a lovely people. It may sound too good to be true but it all exists in Europe's nearest truly exotic foreign country: Morocco. The Atlas Mountains, which sweep across from north-east to south-west, separating 'the desert and the sown', offer a climber's paradise. Quite why the Atlas has suffered neglect by climbers from Britain is hard to understand. Perhaps the names are too difficult - there's no kudos in reporting unpronounceable climbs - or the information is hidden away in French publications. 1 Time the cat escaped from out of the bag. I spent a winter in the Atlas in 1965 and repeated this delight in 1966. Having gone there specifically to climb (Notes in AJ 1966) I ended simply hooked on the whole Atlas ambience and began to wander rather than be restricted to one area. The natural outcome of this was an end-to-end trek 2 in 1995 : 96 days, 900 miles and about 30 peaks bagged. Farfrom rounding off my knowledge, the trip introduced me to a score of new worthy areas to visit and I've had five Atlas months every year since. 3 The scope for climbing is vast. The country must have 50 limestone gorges, miles long and up to 2000 feet deep, each ofwhich would fill volumes ofclimbs if located in Europe, while on the mountains there are crests to be traversed and notable granite faces still virgin. -

Winter Mountaineering in Morocco

MOROCCO - Winter Mountaineering in Morocco OVERVIEW Mt Toubkal, known locally as Jebel Toubkal stands 4167m above sea level and commands superb views of the High Atlas Mountains. Toubkal sits on the eastern edge of a spectacular cirque ringing the head of the Mizane valley which contains numerous other peaks over 4000m. Nestling at the base of Toubkal are two mountain refuges, providing an excellent base to enjoy the superb range of winter mountaineering and climbing to be found here. Despite its latitude, this region receives good snowfall each year, and some years snow reaches depths of several metres. With ridges, icefalls, gullies, spectacular peaks, easy ascents to summer passes, there is more than enough here to please anyone’s aspirations. Combine this winter wonderland with some time in exotic Marrakech and you get the full hit of everything in Morocco; hustlers, markets, wacky spices, beautiful mountains, great food and really friendly people make it a trip to be remembered for a long time”. MOUNT TOUBKAL FOR WINTER CLIMBING North Africa’s highest mountain offers a unique opportunity to do some fine winter mountaineering and ice climbing at grades I to III. The week will cover: Snow belays, Rock and Ice anchors, multi-pitch climbing, route choice, avalanche avoidance, and movement techniques. Throughout the course we will aim to ascend some classic routes on Morocco’s 4000m peaks. All specialist equipment can be hired. Participation Statement Adventure Peaks recognises that climbing, hill walking and mountaineering are activities with a danger of personal injury or death. Participants in these activities should be aware of and accept these risks and be responsible for their own actions and involvement. -

TOUBKAL 4.167M

Xavi Llongueras i Orriols. Guia d'Alta Muntanya UIAGM. C/ Rodeig, 1. 25727 Prullans. Tel. 34 - 676 510 655 [email protected] www.guiallongueras.com TOUBKAL 4.167m Toubkal 4167m ascent program, the highest point in Atlas by ski mountaineering. The ascent to the highest peak in Morocco 4167m by ski mountaineering. Let yourself be enthralled by this exotic region; let yourself be led up Toubkal by professional guides. Visit the mysterious souk in Marrakesh with its snake-charmers. Enjoy exceptional trekking only 2 hours by plane from Barcelona or Madrid. In addition we have other ascents of Toubkal peaks around this massif, such as Akioud of 3900m, the 4015m of Ras n'Ouanoukrim or Imeghras of 3900m3900m. www.guiallongueras.com Xavi Llongueras i Orriols. Guia d'Alta Muntanya UIAGM. C/ Rodeig, 1. 25727 Prullans. Tel. 34 - 676 510 655 [email protected] www.guiallongueras.com Itinerary Day 1: Flight from your country to Marrakesh. Pick up the group at the airport and transport to Imlil village at 1740m by private transport. At the Atlas range mountains. Hotel (D) Day 2: After breakfast we'll take contact with our men's mules, who will helpus to bring up our bagage till the mountain hut. Depending of thhe snow they will carry the bagage by mulles or by themselves. We'll start up the Assif n'Isougouane valley till Sidi Chamaharouch a 2350m, where we'll make a short stop. From here we'll up following the trail to the Toubkal mountain hut at 3207m. 3-4 hours. 1450m. Refuge (B, L, D) Day 3: Summit acclimatisation in the area. -

Rapport D'activités 2015 (Pdf)

Rapport annuel des activités menées dans le Parc National de Toubkal au titre de l’année 2015 I. PRESENTATION DU PARC NATIONAL DE TOUBKAL Créé par arrêté viziriel le 19 janvier 1942, suite à la tenue du 9ème Congrès de l’Institut des Hautes Etudes Marocaines, portant sur la haute montagne, en 1937, le Parc National de Toubkal (PNTb) est le 1er parc national à avoir vu le jour au Maroc. Il fut établi dans la région du Haut Atlas, une des régions les plus riches en biodiversité. Chevauchant sur trois provinces – Al Haouz, Taroudant et Ouarzazate – cette aire protégée est située à 75km au sud de la ville de Marrakech, entre la vallée de l’oued Ourika à l’Est et la vallée du N’Fis à l’Ouest. Le PNTb, proprement dit, s’étend sur une superficie de 38.000 ha, à laquelle s’ajoutent 62.000 ha de zone périphérique, proposée en 1996 dans le Plan Directeur d’Aménagement et de Gestion du parc. I.1 Données générales Situation administrative : - Provinces : Al Haouz, Taroudant et Ouarzazate. - Communes rurales concernées : Asni, Ouirgane, Imegdal, Ijoukak, Oukaïmeden, Setti Fadma, Toubkal, Ahl Tifnoute et Tidili. Situation forestière : - Direction Régionale des Eaux et Forêts et de la Lutte Contre la Désertification : Haut Atlas (versant nord du PNTb) et Sud-ouest (versant sud du PNTb). - Directions Provinciales des Eaux et Forêts et de la Lutte Contre la Désertification : Marrakech (versant nord du PNTb), Taroudant et Ouarzazate (versant sud du PNTb). - Secteurs forestiers : Ouirgane, Ijoukak, Ifghane, Agaïouar, Asgaour, Idergane et Ighrem n’Ougdal. - Zones du PNTb : Zones d’Ouirgane, d’Imlil et de Setti Fadma au PNTb. -

Nota Lepidopterologica

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nota lepidopterologica Jahr/Year: 2012 Band/Volume: 35 Autor(en)/Author(s): Bartsch Daniel Artikel/Article: Revision of types of several species of Bembecia Hübner, 1819 from northern Africa and southwestern Europe (Sesiidae) 125-133 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Notalepid. 35 (2): 125-133 125 Revision of types of several species of Bembecia Hübner, 1819 from northern Africa and southwestern Europe (Sesiidae) Daniel Bartsch Staatliches Museum fur Naturkunde Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany; [email protected] Received 14 March 2012; reviews returned 18 April 2012; accepted 18 August 2012. Subject Editor: Jadranka Rota. Abstract. The type specimens of Sesia sirphiformis Lucas, 1 849 from Lac Tonga in Algeria and Dipso- sphecia megillaeformis v. tunetana Le Cerf, 1 920 syn. n. from the vicinity of Tunis were examined and found to be conspecific. Bembecia sirphiformis belongs to the B. ichneumoniformis (Denis & Schiffer- müller, 1775) species group and is currently known only from northern Africa. Records from Sicily, Sar- dinia, Corsica, southern Italy, and Morocco (as B. tunetana) are here considered doubtful and may belong to other species. B. astragali (Joannis, 1909) stat. rev., which was described from northern Spain and southern France and was previously considered conspecific with B. sirphiformis, actually appears not to be so closely related to B. sirphiformis and seems to belong to the B. megillaeformis (Hübner, 1813) spe- cies group. B. igueri Bettag & Bläsius, 1998 syn. n. from Morocco is now considered to be a synonym of B. -

Winter Toubkal Trek, Morocco

Winter Toubkal Trek, Morocco This challenge offers a tough but rewarding International Flights trek combining unforgettable winter mountain Flights are not included as part of the challenge scenery with the splendor and colour of costs. You will need to organize your own Morocco. international flights to arrive in Marrakech no later than 1pm on Day 1 (see below). If you plan on coming to Morocco is a country full of mysticism and Marrakech a few days early to help get over the jet lag and explore, you’ll need to meet the group transfer at the mythology, a diverse and spectacular land. In airport no later than 1pm on day 1. Please be sure to the midst of it all lies the High Atlas mountain contact us at [email protected] BEFORE you range, home to Jebel Toubkal, one of the tallest commit and pay for your flights so we can make sure peaks in North Africa. they are in line with the itinerary. We can also help you organize your flights, and put you in touch with our The western High Atlas range known as partners at Flight Centre. Toubkal massif offers a range of peaks over 3900m. This challenge includes two of these highest mountains which are accessible from Day 1: Arrive in Marrakech and climb to Aremd the mountain refuge with great views of the 1950m whole massif. Starting from the Red city of Your connecting flight from Casablanca needs to arrive Marrakech you will journey into the Berber in Marrakech no later than 1pm on this day so you will country to discover the majesty and the beauty be able to meet and take the group transfer.