The Atlas Mountains. and at 5.30 A.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatiotemporal Patterns of Saharan Dust Outbreaks in the Mediterranean Basin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library 1 Spatiotemporal patterns of Saharan dust outbreaks in the Mediterranean Basin 2 3 György Vargaa*, Gábor Újvárib & János Kovácsc,d 4 5 aGeographical Institute, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Hungarian 6 Academy of Sciences, Budaörsi út 45, H-1112 Budapest, Hungary (E-mail: 7 [email protected]) 8 bGeodetic and Geophysical Institute, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, 9 Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Csatkai E. u. 6-8, H-9400 Sopron, Hungary (E-mail: 10 [email protected]) 11 cDepartment of Geology & Meteorology, University of Pécs, Ifjúság u. 6, H-7624 Pécs, 12 Hungary (E-mail: [email protected]) 13 dEnvironmental Analytical & Geoanalytical Research Group, Szentágothai Research 14 Centre, University of Pécs, Ifjúság u. 20, H-7624 Pécs, , Hungary 15 16 *Corresponding author – E-mail: [email protected] 17 18 Abstract 19 20 Saharan dust outbreaks transport appreciable amounts of mineral particles into the atmosphere 21 of the Mediterranean Basin. Atmospheric particulates have significant impacts on numerous 22 atmospheric, climatic and biogeochemical processes. The recognition of background drivers, 23 spatial and temporal variations of the amount of Saharan dust particles in the Mediterranean 24 can lead to a better understanding of possible past and future environmental effects of 25 atmospheric dust in the region. 26 For this study the daily NASA Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer's and Ozone Monitoring 27 Instrument’s aerosol data (1979– 2012) were employed to estimate atmospheric dust amount. -

FAO-GIAHS: Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems a Legacy for the Future!

FAO-GIAHS: Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems A LEGACY FOR THE FUTURE! Our Efforts on Biodiversity in Our Strategy on Biodiversity Do you believe in the role of Development Cooperation Our Aichi Priorities family farming communities espe- FACT 1 goal cially women in conservation and A sustainable use of biodiversity ? Leverage global and national recognition of Mainstreaming the importance of agricultural heritage systems 2 3 and its biodiversity for their institutional support Integration 1 4 Awareness Place your post-its with and safeguard 5 Jane dela Cruz ©FAO/Mary 0 Incentives 2 Resource Mobilization your answer below: Resources 6 Photo: FACT 2 Sustainable Use Use of Natural goal 1 to 20 The Aichi 9 Supporting active and informed participation of Biodiversity B 1 Loss of Habitats 7 Knowledge E Targets goal The GIAHS Initiative in China have brought significant indigenous and local communities in biodiversity Sustainable Fisheries Enhancing Areas Under Sust. Management 8 Implementation 8 Pollution development in Qingtian, our government and local management and conservation Traditional Knowledge 1 9 Invasive Alien Species community have come to understand the value of our V FACT 3 Short Term ulnerable Ecosystems National Biodiversity 1 7 Strategies traditional rice fish culture and biodiversity. Agriculture is 0 1 Coordination and harmonization of activities to a way of our lives and to live in harmony with nature... Protected Areas Agricultural Biodiversity Preventing Extinctions promote efficient management of resources and 1 Access and 1 6 Benefit Sharing “Traditional rice fish provides us organic food products, which sells higher than 1 encourage multi-stakeholder participation Medium Term non-organic, and making our annual higher than before. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 13 April 2015 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Kaislaniemi, L. and van Hunen, J. (2014) 'Dynamics of lithospheric thinning and mantle melting by edge-driven convection : application to Moroccan Atlas mountains.', Geochemistry, geophysics, geosystems., 15 (8). pp. 3175-3189. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005414 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2014. The Authors. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modications or adaptations are made. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk PUBLICATIONS Geochemistry, -

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

Study of the Interannual Rainfall Variability in Northern Algeria Etude De La Variabilite Inter-Annuelle Des Pluies De L'algerie Septentrionale

Revue scientifique et technique. LJEE N°23. Décembre 2013 STUDY OF THE INTERANNUAL RAINFALL VARIABILITY IN NORTHERN ALGERIA ETUDE DE LA VARIABILITE INTER-ANNUELLE DES PLUIES DE L'ALGERIE SEPTENTRIONALE Mohamed MEDDI. École Nationale Supérieure d’Hydraulique, Blida, LGEE. [email protected] Samir TOUMI . École Nationale Supérieure d’Hydraulique, Blida, LGEE. ABSTRACT : The work presented here focuses on the inter-annual variability of annual rainfall in Northern Algeria. This work is carried out by using the coefficient of variation (the ratio between the standard deviation and the average). We will try to show areas of low, medium and high variations in Northern Algeria. In order to do this, we use 333 rainfall stations spread over the entire study area, with a measurement period of 37 years (1968/2004). The contrast of rainfall spatial and temporal distribution has been demonstrated by studying the sixteen basins, as adopted by the National Agency of Water Resources. The high spatial variability characterizes the basins of the High Plateaus of Constantine and Chot El Hodna. Keywords: Northern Algeria - annual Rainfall - inter-annual variability - coefficient of variation RESUME : Nous présentons dans cet article une étude de la variabilité interannuelle des pluies annuelles en Algérie septentrionale. Ce travail a été réalisé en utilisant le coefficient de variation (le rapport entre l'écart-type et la moyenne). Nous essayerons de montrer les zones à faible, moyenne et forte variations dans le Nord de l'Algérie. Pour se faire, nous avons utilisé 333 postes pluviométriques réparties sur l'ensemble de la zone d'étude avec une période de mesure de 37 ans (1968/2004). -

Rowan C. Martindale Curriculum Vitae Associate Professor (Invertebrate Paleontology) at the University of Texas at Austin

ROWAN C. MARTINDALE CURRICULUM VITAE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR (INVERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY) AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Department of Geological Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Jackson School of Geosciences Website: www.jsg.utexas.edu/martindale/ 2275 Speedway Stop C9000 Orchid ID: 0000-0003-2681-083X Austin, TX 78712-1722 Phone: 512-475-6439 Office: JSG 3.216A RESEARCH INTERESTS The overarching theme of my work is the connection between Earth and life through time, more precisely, understanding ancient (Mesozoic and Cenozoic) ocean ecosystems and the evolutionary and environmental events that shaped them. My research is interdisciplinary, (paleontology, sedimentology, biology, geochemistry, and oceanography) and focuses on: extinctions and carbon cycle perturbation events (e.g., Oceanic Anoxic Events, acidification events); marine (paleo)ecology and reef systems; the evolution of reef builders (e.g., coral photosymbiosis); and exceptionally preserved fossil deposits (Lagerstätten). ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin September 2020 to Present Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Austin August 2014 to August 2020 Postdoctoral Researcher, Harvard University August 2012 to July 2014 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology; Mentor: Dr. Andrew H. Knoll. EDUCATION Doctorate, University of Southern California 2007 to 2012 Dissertation: “Paleoecology of Upper Triassic reef ecosystems and their demise at the Triassic-Jurassic extinction, a potential ocean acidification event”. Advisor: Dr. David J. Bottjer, degree conferred August 7th, 2012. Bachelor of Science Honors Degree, Queen’s University 2003 to 2007 Geology major with a general concentration in Biology (Geological Sciences Medal Winner). AWARDS AND RECOGNITION Awards During Tenure at UT Austin • 2019 National Science Foundation CAREER Award: Awarded to candidates who are judged to have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education. -

And Others a Geographical Biblio

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 108 SO 001 480 AUTHOR Lewtbwaite, Gordon R.; And Others TITLE A Geographical Bibliography for hmerican College Libraries. A Revision of a Basic Geographical Library: A Selected and Annotated Book List for American Colleges. INSTITUTION Association of American Geographers, Washington, D.C. Commission on College Geography. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Commission on College Geography, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85281 (Paperback, $1.00) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 BC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, Booklists, College Libraries, *Geography, Hi7her Education, Instructional Materials, *Library Collections, Resource Materials ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography, revised from "A Basic Geographical Library", presents a list of books selected as a core for the geography collection of an American undergraduate college library. Entries numbering 1,760 are limited to published books and serials; individual articles, maps, and pamphlets have been omii_ted. Books of recent date in English are favored, although older books and books in foreign languages have been included where their subject or quality seemed needed. Contents of the bibliography are arranged into four principal parts: 1) General Aids and Sources; 2)History, Philosophy, and Methods; 3)Works Grouped by Topic; and, 4)Works Grouped by Region. Each part is subdivided into sections in this general order: Bibliographies, Serials, Atlases, General, Special Subjects, and Regions. Books are arranged alphabetically by author with some cross-listings given; items for the introductory level are designated. In the introduction, information on entry format and abbreviations is given; an index is appended. -

Crustal Versus Asthenospheric Origin of the Relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco

Crustal versus asthenospheric origin of the relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Y. Missenard, H. Zeyen, D. Frizon de Lamotte, P. Leturmy, C. Petit, M. Sebrier To cite this version: Y. Missenard, H. Zeyen, D. Frizon de Lamotte, P. Leturmy, C. Petit, et al.. Crustal versus astheno- spheric origin of the relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.. Journal of Geophysical Research, American Geophysical Union, 2006, 111, pp.B03401. 10.1029/2005JB003708. hal-00092374 HAL Id: hal-00092374 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00092374 Submitted on 1 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 111, B03401, doi:10.1029/2005JB003708, 2006 Crustal versus asthenospheric origin of relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco Yves Missenard,1 Hermann Zeyen,2 Dominique Frizon de Lamotte,1 Pascale Leturmy,1 Carole Petit,3 Michel Se´brier,3 and Omar Saddiqi4 Received 2 March 2005; revised 18 October 2005; accepted 9 November 2005; published 1 March 2006. [1] We investigate the respective roles of crustal tectonic shortening and asthenospheric processes on the topography of the High Atlas and surrounding areas (Morocco). -

C:\GQ 48 (1)\Internet\GQ48(1).Vp

Geological Quarterly, 2004, 48 (1): 89–96 Reptile tracks (Rotodactylus) from the Middle Triassic of the Djurdjura Mountains in Algeria Zbigniew KOTAÑSKI, Gerard GIERLIÑSKI and Tadeusz PTASZYÑSKI Kotañski Z., Gierliñski G. and Ptaszyñski T. (2004) — Reptile tracks (Rotodactylus) from the Middle Triassic of Djurdjura Mountains in Algeria. Geol. Quart., 48 (1): 89–96. Warszawa. In 1983, during stratigraphic investigations in the Djurdjura Mountains, vertebrate tracks were discovered in the Middle Triassic Haizer–Akouker Unit at the Belvédère (Bkherdous) locality in Algeria. The footprints are about 2 cm long and consist of impressions of four clawed digits (I–IV), plus a reverted digit V. Manus imprints were overstepped by those of the pes. Originally interpreted as lizard footprints, they have been recently diagnosed as Rotodactylus cf. bessieri Demathieu 1984. In the current literature, Rotodactylus trackmakers are regarded as a group closest to dinosaurs among stem archosaurs. The footprints demonstrate a terrestrial sedimentary re- gime in the Maghrebids area during the ?late Anisian. Zbigniew Kotañski, Gerard Gierliñski, Polish Geological Institute, Rakowiecka 4, PL-00-975 Warszawa, Poland; Tadeusz Ptaszyñski, ul. Stroñska 1 m 12, PL-01-461 Warszawa, Poland; e-mail: [email protected]. (received: August 15, 2003; accepted: January 12, 2004). Key words: Palaeoichnology, stratigraphy, Djurdjura Mountains, Middle Triassic, Rotodactylus, footprints. INTRODUCTION ral cast of a left pes imprint of the ichnogenus Rotodactylus Peabody, 1948, cf. Rotodactylus matthesi Haubold, 1967, at- tributable to ornithosuchian archosaurs. The presence of Rotodactylus tracks was noted in the geological section from In spring of 1983, one of us (Z. K.) was looking for Middle the Djurdjura Mountains in a symposium presentation on Triassic diplopores near a road along the main ridge of the diplopores from the same sequence (Kotañski, 1995). -

Boualem N. & Benhamou M

REVUE DE VOLUME 36 (2 ) – 2017 PALÉOBIOLOGIE Une institution Ville de Genève www.museum-geneve.ch Revue de Paléobiologie, Genève (décembre 2017) 36 (2) : 433-445 ISSN 0253-6730 Mise en évidence d’un Albien marin à céphalopodes dans la région de Tiaret (Algérie nord-occidentale) : nouvelles données paléontologiques, implications biostratigraphiques et paléogéographiques Noureddine BOUALEM & Miloud BENHAMOU Université d’Oran 2, Mohamed Ben Ahmed, Faculté des Sciences de la Terre et de l’Univers, Département des Sciences de la Terre, Laboratoire de Géodynamique des Bassins et Bilan Sédimentaire (GéoBaBiSé), BP. 1015, El Mnaouer 31000, Oran, Algérie. E-mail : [email protected] Résumé Dans la localité de Mcharref (Tiaret, Algérie nord-occidentale) un nouveau gisement fossilifère à céphalopodes d’âge albien supérieur (Crétacé inférieur) est mis en évidence dans la « Formation de Mcharref ». Il s’agit de marno-calcaires contenant une riche faune de bivalves/huîtres, échinides, gastéropodes, ostracodes, foraminifères benthiques et planctoniques. Les céphalopodes se trouvent dans le membre inférieur (niveau à ammonites, n° 6). L’étude des ammonites a permis d’établir une attribution biostratigraphique précise. La zone à Mortoniceras pricei est mise en évidence grâce à la détermination d’un Elobiceras (Craginites) sp. aff. newtoni Spath, 1925. Une interprétation paléoenvironnementale et paléogéographique est proposée grâce à l’étude des différents faciès présents dans cette formation. Mots-clés Algérie, Tiaret, Formation de Mcharref, Albien supérieur, ammonites. Abstract Evidence of a marine Albian in Tiaret region (north-western Algeria) : new paleontological data, biostratigraphic and paleogeo- graphic implications.- In the locality of Mcharref (Tiaret, Algeria northwest), an Upper Albian (Lower Cretaceous) new fossiliferous deposit with cephalopods is reported in the “Mcharref Formation”. -

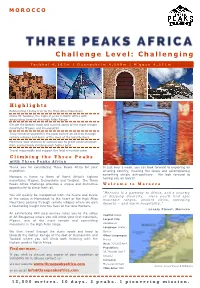

Challenge Level: Challenging

MOROCCO Challenge Level: Challenging Toubkal 4,167m | O u a n o u k r i m 4 , 0 8 9 m | M ’ g o u n 4 , 0 7 1 m H i g h l i g h t s Exhilarating 10 day trek to the High Atlas Mountains Climb Mt Toubkal, the highest peak in North Africa with astounding views of the High Atlas Range Get off the beaten track and summit some of the most remote mountains M’goun and Ouanoukrim Truly immerse yourself in the local culture as we trek through remote villages and learn of the lives of the local Berbers Maximise your chances of success due to great acclimatisation from successively climbing each higher peak Travel responsibly and support the local mountain crew Climbing the Three Peaks with Three Peaks Africa Thank you for considering Three Peaks Africa for your In just over a week, you can look forward to exploring an expedition. amazing country, meeting the locals and accomplishing something simply extraordinary. We look forward to Morocco is home to three of North Africa’s highest having you on board! mountains; M’goun, Ouanoukrim and Toubkal. The Three Peaks Africa Challenge provides a unique and distinctive Welcome to Morocco opportunity to climb them all. “Morocco is a gateway to Afr ica, and a country You will quickly be transported from the hustle and bustle of d iz zy ing d ivers ity . Here you’ ll f ind ep ic of the souks in Marrakech to the heart of the High Atlas mountain ranges, anc ie nt c ities, sweeping Mountains passing through remote villages where we gain deserts – and warm hospitality .” a fascinating insight into the lives of the local Berbers. -

Discover Ltd / Education for All Morocco Y6 – Y7 Geography Transition Unit

Discover Ltd / Education for All Morocco Y6 – Y7 Geography Transition Unit For Primary School Leaders and Teachers June 2020 Dear Colleague I am delighted to attach a copy of the Y6-7 Geography Transition Unit. This unit of work has been designed to address the needs of Year 6 pupils in primary schools as they prepare for their transition into Year 7 at their secondary school. It has been prepared now (May 2020) in an attempt to address any uncertainty around school openings and traditional transition arrangements. We at Discover Ltd and Education for All Morocco decided to use the wealth of resources we have collected over many years for a variety of audiences to prepare a unit of home or school-based study around the ‘geography’ of Morocco. Our intention is that this supports: a) primary school colleagues planning home learning units; b) provides Year 6 pupils with a high quality study pack which aims to develop and enhance their knowledge, skills and understanding across the 3 key aims of the NC for Geography (skills; places / context; and physical / human geography); and c) supports secondary school colleagues as you revise and modify your traditional transition arrangements this term, should you not be able to hold face-to-face sessions with your new Year 7 intake of students. The aim is then that the pupils in Year 6 would bring their ‘completed’ study pack with them at the start of Year 7 to share with their geography teacher. We fully recognise that this is but a tiny part of the primary-secondary transition process but we hope that it makes that step from Y6-Y7 that little bit easier and slightly less stressful for Y6 pupils’.