Policy Stalemate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

1999/1 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #1 1 1999 Virginia Open THE 1999 VIRGINIA OPEN played Jan 22-24 in Fredricksburg, saw a 3-way tie for 1st in the Open section between Adrian Negulescu, Emory Tate & Leonid Filatov. Each scored 4-1. Lance Rackham tal- 1 1 lied 5 ⁄2- ⁄2 to claim clear 1st in the Amateur section. The Open winners rose to the top by different meth- ‹óóóóóóóó‹ ods. Negulescu, a visiting IM from Rumania, took õÏ›‹Ò‹ÌÙ›ú the “professional” route, jumping out 3-0 and then taking it easy on the last day, drawing fellow IMs õ›‡›‹›‹·‹ú Larry Kaufman and Richard Delaune in fairly bloodless fashion. Tate, a co-winner last year as well, õ‹›‹·‹›‡›ú had to fight back from behind this time after losing to Negulescu in round 3. He accomplished the task õ›‹Â‹·‹„‹ú in fine style, jumping all over Kaufman right out of õ‡›fi›fi›‹Ôú the opening in the final round. Filatov executed the semi Swiss Gambit, conceding a draw in the very õfl‹›‰›‹›‹ú first round and piling up points thereafter against mostly lower-rated opposition. õ‹fl‹›‹Áfiflú õ›‹›‹›ÍÛ‹ú Larry Kaufman - Emory Tate Sicilian ‹ìììììììì‹ Notes by Macon Shibut 25...Qxg5! (When the smoke clears Black gets more 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 f3 e5 6 Nb3 than enough for his queen in view of the possible Be7 7 c4 a5 8 Be3 a4 9 N3d2 0-0 10 Bd3 Nc6 11 a3 fork on e4) 26 Qxg5 Rxf2 27 Rxf2 Nxf2 28 Qxg6 (evidently an error) 11...Nd7! 12 0-0 Bg5 13 Bf2 Nfxe4 (Now Black will regroup his pieces for a com- Nc5 14 Bc2 Nd4! (White is already remarkably tied bined attack on White’s king, while White can only up, with hardly any moves.) 15 f4!? (Under the cir- hope for perpetual check.) 29 g4 Rf8 30 g5 Nd2! 31 cumstances you can’t fault White for trying this. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 16/11/2020 17:49 Page 3

01-01 Cover - December 2020_Layout 1 16/11/2020 18:39 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 16/11/2020 17:49 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Bruce Pandolfini ............................................................7 We discover all about the famous coach and Queen’s Gambit adviser Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein A Krushing Success .............................................................................................8 Website: www.chess.co.uk Irina Krush and Wesley So were victorious in the U.S. Championships Subscription Rates: Escapism!..............................................................................................................14 United Kingdom Matthew Lunn headed for the Dolomites along with some friends 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Magnusficent......................................................................................................18 3 year (36 issues) £125 Magnus Carlsen has produced the odd instructive effort of late Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................22 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 -

Playing the Petroff Swapnil Dhopade

Playing the Petroff By Swapnil Dhopade Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Contents Key to Symbols used & Bibliography 4 Preface 5 Third Move Alternatives 1 3.¥c4?! & 3.¤c3 7 2 3.d4 21 3 6.¤xd7 55 3.¤xe5 d6 4 4th Move Alternatives 75 4.¤f3 ¤xe4 5 5.¥d3 & 5.c4 102 6 5.d3 123 7 5.£e2 139 Old Main Line 8 5.d4 154 9 9.£c2 169 10 9.¤c3 186 Modern Main Line 11 5.¤c3 200 12 11.¢b1 & 11.¦he1 221 Avoiding the Petroff 13 Centre Game 240 14 King’s Gambit 264 15 Vienna Game 287 16 Bishop’s Opening 301 Appendix: Konguvel Ponnuswamy – Swapnil Dhopade 317 Variation Index 320 Preface Welcome, dear readers, to my first opening book – on the Petroff Defence. The idea for this book first occurred during the 2018 Olympiad in Batumi, Georgia, an event which marked a turning point in my career. Having become a grandmaster in 2016, I had been coaching talented youngsters (including GM Raunak Sadhwani, who became a GM at just 13 years of age!) for quite a while and preparing opening files for them. In 2018, I was given the opportunity to work as part of a team of seconds, headed by GM Jacob Aagaard, helping the Indian Women’s team at the Olympiad. Performing this work at a world-class competition required me not only to prepare opening ideas at a more intricate level, but also to supplement my ChessBase analysis with brief but lucid comments at critical moments, to help the players retain the most important information. -

Saturday Enrichment Fall 2019 Introduction to Chess: Exercising Your Brain

SATURDAY ENRICHMENT FALL 2019 INTRODUCTION TO CHESS: EXERCISING YOUR BRAIN Instructor: Cary R. Easterday Instructor Email: [email protected] Location: Loew Hall 118 Course Description A healthy lifestyle includes physical and mental fitness. Playing chess improves memory, concentration, foresight, math skills, reading skills, creativity, and problem-solving skills. Each week the instructor will provide puzzles, lessons, videos, and one-on-one play, monitor student progress, and help with questions. Lessons include setup, piece movements, strategy, tactics, openings, middlegame, endgame, chess notation, popular variants, and history. No experience is necessary. Learning Outcomes By the end of this course, students should be able to: • Play standard chess, including such moves as castle, en passant, and pawn promotion. • Demonstrate chess tactics such as forks, pins, skewers, batteries, discovered attacks, undermining, overloading, deflection, and sacrifices. • Record games using algebraic and descriptive chess notations. • Play popular chess variants such as Bughouse, Chess960, Transcendental, King of the Hill, Upside-down, Atomic, Pawns Game, Peasants’ Revolt, and four-player Quad Kingdom. • Play in a chess tournament, if they choose (optional participation). Instructional Strategies • The instructor uses inquiry-based instruction to inspire student creativity and problem- solving abilities. • Students play chess games via cooperative learning and differentiation. • Each student receives a gold membership to Chesskid.com and has access to technology (computers, notebooks, phones) to solve chess puzzles, take self-paced chess lessons, and play online chess games with computer bots or other students. Student Assessment There is no formal assessment for this course. The instructor will observe one-on-one play each week and will informally assess a student’s progress as they answer questions, solve puzzles, and progress in lessons/ranking on Chesskid.com. -

The Petroff Defence Cyrus Lakdawala

opening repertoire the Petroff defence Cyrus Lakdawala www.everymanchess.com About the Author is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cyrus Lakdawala Champion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire: ...c6 First Steps: the Modern Caruana: Move by Move Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 6 1 The Cochrane Gambit 14 2 The Scotch Petroff 32 3 The Main Line Petroff 98 4 The Main Line Sidelines 190 5 The New Main Line 251 6 The Three Knights Petroff 303 Introduction W________W [rhb1kgW4] [0p0pDp0p] [WDWDWhWD] [DWDW0WDW] [WDWDPDWD] [DWDWDNDW] [P)P)W)P)] [$NGQIBDR] W--------W What is Your Opening Utopia? In the foolishness of youth I took a vast dislike to the Petroff, a hateful creature with no perceivable reason to exist, other than to annoy 1 e4 players. -

An Analysis of the Ideologies, Strategies and Applications of Chess and Martial Arts with Respect to Transferable Skills Torriente Toliver Langston University

Langston University Digital Commons @ Langston University McCabe Thesis Collection Student Works 5-2008 An Analysis of the Ideologies, Strategies and Applications of Chess and Martial Arts With Respect to Transferable Skills Torriente Toliver Langston University Follow this and additional works at: http://dclu.langston.edu/mccabe_theses Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Sociology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Toliver, Torriente, "An Analysis of the Ideologies, Strategies and Applications of Chess and Martial Arts With Respect to Transferable Skills" (2008). McCabe Thesis Collection. Paper 46. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ Langston University. It has been accepted for inclusion in McCabe Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Langston University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THE IDEOLOGIES, STRATEGIES, AND APPLICATIONS OF CHESS AND MARTIAL ARTS WITH RESPECT TO TRANSFERABLE SKILLS By Torriente Toliver Acknowledgements This work would not be possible without the training in the skills that I learned to transfer. I want to thank Allen Hammond, my high school chess coach and world history teacher, who taught me the value of information, research, and critical thinking. I would also like to thank the staff of Beverly Pagoda Martial Arts Academy who taught me to put my critical thinking skills to use with practical application and not to waste them on pontification. I would like to thank Sensei Kates Jr. specifically because it was he that taught me about transferable skills and inspired me to create an effective way to analyze my skills and teach others to do the same. -

A Beginner's Guide to Coaching Scholastic Chess

A Beginner’s Guide To Coaching Scholastic Chess by Ralph E. Bowman Copyright © 2006 Foreword I started playing tournament Chess in 1962. I became an educator and began coaching Scholastic Chess in 1970. I became a tournament director and organizer in 1982. In 1987 I was appointed to the USCF Scholastic Committee and have served each year since, for seven of those years I served as chairperson or co-chairperson. With that experience I have had many beginning coaches/parents approach me with questions about coaching this wonderful game. What is contained in this book is a compilation of the answers to those questions. This book is designed with three types of persons in mind: 1) a teacher who has been asked to sponsor a Chess team, 2) parents who want to start a team at the school for their child and his/her friends, and 3) a Chess player who wants to help a local school but has no experience in either Scholastic Chess or working with schools. Much of the book is composed of handouts I have given to students and coaches over the years. I have coached over 600 Chess players who joined the team knowing only the basics. The purpose of this book is to help you to coach that type of beginning player. What is contained herein is a summary of how I run my practices and what I do with beginning players to help them enjoy Chess. This information is not intended as the one and only method of coaching. In all of my college education classes there was only one thing that I learned that I have actually been able to use in each of those years of teaching. -

A Conversation with a Ten Year Old Author

YOUNG GUNS Oliver Boydell came up with a simple plan: language because my goal was to teach the 1. Pick exciting games from the past important chess concepts 2. Make the notes breezy and brief and this is best done when 3. Use lots of diagrams the language is clear and 4. Have questions for the reader with answers everyone – kids and adults – in the back of the book can understand. 5. Have a “lesson” or two, a concept, to take with them that they should remember How do you go through a about playing good chess game? Do you take notes? 6. Give a favorite move – one that might Do you use a chess engine stick with the reader. as you go? I take notes on what I think For the miserable types that give a is interesting. I might go disapproving “harumph” to all this, you’ve over it several times to By Pete Tamburro forgotten what it is to be a kid. make sure I didn’t make any mistakes, like missing an Our chat was fun and we share it here. obvious tactic. I would use the engine several times, even different engines, to make sure I agreed with ack in 2010, I was assigned to How does it feel to be an the evaluation. I also look write a review of a 14-year- author? for certain ideas I can write old boy’s first chess book, I’m proud of myself and am about, like doubling rooks Mastering Positional Chess. really excited. I had never attacking games. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

Dynamic Pawn Play in Chess Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DYNAMIC PAWN PLAY IN CHESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Drazen Marovic | 256 pages | 01 Sep 2001 | Gambit Publications Ltd | 9781901983432 | English | London, United Kingdom Dynamic Pawn Play in Chess PDF Book Product Details This follow-up to the author's successful Understanding Pawn Play in Chess addresses issues that are central to understanding chess by tackling fundamental questions such as "How should pawns be used to fight for the center? Get A Copy. The idea is to double the rooks on the c file and once the knight reaches b4 sacrifice the exchange on c3. Chern S. What are the differences between Dynamic and Static? I disagree, Wining chess means tactical and strategic positioning of all pieces synchronized all together to attain safety of the king and mating the opponent. Here is a test position:. Original Title. Paul Britt added it May 29, Buying from Chess House gives you easy access to parts for many years so your set is always playable. I would distinguish between two basic elements. This follow-up to the author's successful Understanding Pawn Play in Chess addresses issues that are central to understanding chess by tackling fundamental questions such as "How should pawns be used to fight for the center? S:d4 a6 9. Intuition is necessary not only during the entire dynamic phase but also in that precise moment when one decides to change the course of the game. These questions are central to understanding chess, and are the primary subject-matter of this book. All of these ideas got me thinking. More filters. -

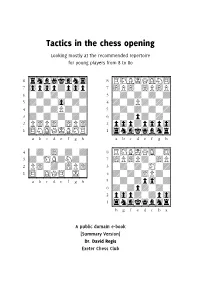

Tactics in the Chess Opening

Tactics in the chess opening Looking mostly at the recommended repertoire for young players from 8 to 80 cuuuuuuuuC cuuuuuuuuC (rhb1kgn4} (RHBIQGN$} 70p0pDp0p} 7)P)w)P)P} 6wDwDwDwD} 3wDwDwDwD} 5DwDw0wDw} &dwDPDwDw} &wDwDPDwD} 5wDwDwdwD} 3DwDwDwDw} 6dwDpDwDw} 2P)P)w)P)} 2p0pdp0p0} %$NGQIBHR} %4ngk1bhr} v,./9EFJMV v,./9EFJMV cuuuuuuuuC &wDw)wDwD} (RHBIQGw$} 3dwHBDNDw} 7)P)Pdw)P} 2P)wDw)P)} 3wDwDwHwD} %$wGQ$wIw} &dwDw)PDw} v,./9EFJMV 5wDwDp0wD} 6dwDpDwDw} 2p0pdwdp0} %4ngk1bhr} vMJFE9/.,V A public domain e-book [Summary Version] Dr. David Regis Exeter Chess Club Contents Introduction.................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. PLAYING WHITE WITH 1. E4 E5.......................................... ERROR ! B OOKMARK NOT DEFINED . Scotch Gambit ................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Italian Game ................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Evans' Gambit................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. Italian Game ................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Two Knights'................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Petroff Defence............................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Elephant Gambit............................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. Latvian Gambit ............................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Philidor's Defence..........................................