The Pirc Move by Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6Th London Chess Classic (6-14 December 2014)

6TH LONDON CHESS CLASSIC (6-14 DECEMBER 2014) CLASSIC ROUND 4: 14 DECEMBER 2014 YOU’VE JUST BEEN SPACEBARRED With one round to go (starting at 2pm on Sunday), the Classic is nicely poised with five of the six players still able to finish first. Round four featured just the one decisive result, with Hikaru Nakamura beating Mickey Adams, which makes the scores as follows: Kramnik and Giri 6, Nakamura 5, Anand and Adams 4, Caruana 3. One of the great things about an international chess tournament is the exchange of ideas between people from different countries and cultures. From the beginning, the London Chess Classic has placed a great deal of importance on invitees putting in as positive a performance in the commentary room as they do at the board. Top chessplayers are highly intelligent people and have quickly realised that their livelihood depends as much on their ability to communicate as to play good moves. Consequently we now have a young generation of players with the confidence to innovate off the board linguistically as well as on it. Not just those who have English as their first language, either. It’s gratifying for us native Brits to have our language adopted worldwide as the first language of chess, but perhaps a bit scary too. As with our other notable export, football, where we have had to learn to endure other countries playing it a lot better than we do, we now have to live with people from non-English speaking countries being more articulate and creative in English than we are. -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols and Notation 5 Introduction 6 The First Move 8 1 d4 9 Queen’s Gambit Declined 11 Slav and Semi-Slav 27 Queen’s Gambit Accepted 40 Other 1 d4 d5 Openings 46 Nimzo-Indian Defence 57 Queen’s Indian Defence 77 Bogo-Indian Defence 89 King’s Indian Defence 93 Grünfeld Defence 121 Benoni and Benko 140 Other 1 d4 Ìf6 Openings 159 Dutch Defence 174 Other 1 d4 Openings 185 Flank Openings 198 Symmetrical English 199 Reversed Sicilian 222 1 c4 Ìf6 and Other English Lines 233 Réti Opening 248 Other Flank Openings 261 1 e4 269 Ruy Lopez 272 Italian Game 301 4 FUNDAMENTAL CHESS OPENINGS Scotch Opening 312 Four Knights Game 318 Petroff Defence 322 King’s Gambit 328 Other 1 e4 e5 Openings 337 French Defence 347 Caro-Kann Defence 375 Sicilian Defence 389 Alekhine Defence 447 Pirc Defence 453 Other 1 e4 Openings 461 Index of Named Opening Lines 469 Index of Variations 472 SLAV AND SEMI-SLAV Slav and Semi-Slav 1d4 d5 Queen’s Gambit Declined) or he must be pre- 2c4 c6(D) pared to risk some fairly sharp variations where he may have to sacrifice a pawn. rslwkvnt The most radical way of eliminating ...dxc4 is 3 cxd5, the Exchange Variation, yet the W zp+-zpzp main lines of the Slav are to be reached with -+p+-+-+ either 3Ìf3or 3 Ìc3. These two ‘natural de- veloping moves’ will often transpose, but of +-+p+-+- course there are a few important differences. -+PZ-+-+ +-+-+-+- Exchange Variation PZ-+PZPZ 3 cxd5 cxd5 (D) TNVQMLSR rslwkvnt W zp+-zpzp Though not as old as the Queen’s Gambit -+-+-+-+ Declined, the Slav has an excellent record of service and is considered a classical opening. -

Periodiko Arbiters Layout 1

CONTENTS Introduction from FIDE Arbiters’ Commission Chairman.......................................................3 Article 1: Amended Laws of Chess - effective from 1 January 2018.......................4 Article 2: Amended Swiss System Rules - effective from 1 January 2018 .............6 Article 3: Rules Commission - Guidelines for the Organisers..............................................7 Article 4: Pausing Games – Historical Examples..........................................................................9 Cases drawn from recent events and Arbiter reports: A) Case A: Move Counting via Scoresheet...........................................................................11 B) Case B: Illegal Move Vice-Versa ..............................................................................................12 C) Case C: Player Resigns Then Un-Resigns ...........................................................................14 The photos of the Magazine are courtesy of IM Anastazia Karlovich, FIDE Press Officer. The edition was compiled by IA E. Saltamara (GRE). Introduction Introduction from FIDE Arbiters’ Commission Chairman Dear friends, The FIDE Arbiters’ Commission has the pleasure to publish the 6th issue of the Arbiters’ Magazine. We continue our effort to provide Arbiters all over the world with necessary knowledge and information coming from real incidents that happened during recent tournaments, and thus making Arbiters better in exercising their duties. In this issue, we are pleased to cooperate with the FIDE Rules Commission, -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

1999/1 Layout

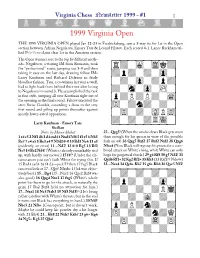

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #1 1 1999 Virginia Open THE 1999 VIRGINIA OPEN played Jan 22-24 in Fredricksburg, saw a 3-way tie for 1st in the Open section between Adrian Negulescu, Emory Tate & Leonid Filatov. Each scored 4-1. Lance Rackham tal- 1 1 lied 5 ⁄2- ⁄2 to claim clear 1st in the Amateur section. The Open winners rose to the top by different meth- ‹óóóóóóóó‹ ods. Negulescu, a visiting IM from Rumania, took õÏ›‹Ò‹ÌÙ›ú the “professional” route, jumping out 3-0 and then taking it easy on the last day, drawing fellow IMs õ›‡›‹›‹·‹ú Larry Kaufman and Richard Delaune in fairly bloodless fashion. Tate, a co-winner last year as well, õ‹›‹·‹›‡›ú had to fight back from behind this time after losing to Negulescu in round 3. He accomplished the task õ›‹Â‹·‹„‹ú in fine style, jumping all over Kaufman right out of õ‡›fi›fi›‹Ôú the opening in the final round. Filatov executed the semi Swiss Gambit, conceding a draw in the very õfl‹›‰›‹›‹ú first round and piling up points thereafter against mostly lower-rated opposition. õ‹fl‹›‹Áfiflú õ›‹›‹›ÍÛ‹ú Larry Kaufman - Emory Tate Sicilian ‹ìììììììì‹ Notes by Macon Shibut 25...Qxg5! (When the smoke clears Black gets more 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 f3 e5 6 Nb3 than enough for his queen in view of the possible Be7 7 c4 a5 8 Be3 a4 9 N3d2 0-0 10 Bd3 Nc6 11 a3 fork on e4) 26 Qxg5 Rxf2 27 Rxf2 Nxf2 28 Qxg6 (evidently an error) 11...Nd7! 12 0-0 Bg5 13 Bf2 Nfxe4 (Now Black will regroup his pieces for a com- Nc5 14 Bc2 Nd4! (White is already remarkably tied bined attack on White’s king, while White can only up, with hardly any moves.) 15 f4!? (Under the cir- hope for perpetual check.) 29 g4 Rf8 30 g5 Nd2! 31 cumstances you can’t fault White for trying this. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Livros De Xadrez

LIVROS DE XADREZ No. TÍTULO Autor Editora 1 100 Endgames You Must Know Jesus de la Villa New In Chess 2 Ajedrez - La Lucha por la Iniciativa Orestes Aldama Zambrano Paidotribo 3 Alexander Alekhine Alexander Kotov R.H.M. Press 4 Alexander Alekhine´s Best Games Alexander Alekhine Batsford Chess 5 Analysing the Endgame John Speelman Batsford Chess 6 Art of Chess Combination Znosko-Borovsky Dover 7 Attack and Defence M.Dvoretsky & A.Yusupov Batsford Chess 8 Attack and Defence in Modern Chess Tactics Ludek Pachman RPK 9 Attacking Technique Colin Crouch Batsford Chess 10 Better Chess for Average Players Tim Harding Dover 11 Bishop v/s Knight: The Veredict Steve Mayer Ice 12 Bobby Fischer My 60 Memorable Games Bobby Fischer Faber & Faber Limited 13 Bobby Fischer Rediscovered Andrew Soltis Batsford 14 Bobby Fischer: His Aproach to Chess Elie Agur Cadogan 15 Botvinnik - One Hundred Selected Games M.Botvinnik Dover 16 Building Up Your Chess Lev Alburt Circ 17 Capablanca Edward Winter McFarland 18 Chess Endgame Quis Larry Evans Cardoza Publishing 19 Chess Endings Yuri Averbach Everyman Chess 20 Chess Exam and Training Guide Igor Khmelnitsky I am Coach Press 21 Chess Middlegames Yuri Averbach Cadogan Chess 22 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 23 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 24 Chess Self-Improvement Zenon Franco Gambit 25 Chess Strategy for the Tournament Player Alburt & Palatnik Circ 26 Creative Chess Amatzia Avni Cadogan Chess 27 Creative Chess Opening Preparation Viacheslav Eingorn Gambit 28 Endgame Magic J.Beasley -

Grandmaster Opening Preparation Jaan Ehlvest

Grandmaster Opening Preparation By Jaan Ehlvest Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Preface This book is about my thoughts concerning opening preparation. It is not a strict manual; instead it follows my personal experience on the subject of openings. There are many opening theory manuals available in the market with deep computer analysis – but the human part of the process is missing. This book aims to fill this gap. I tried to present the material which influenced me the most in my chess career. This is why a large chapter on the Isolated Queen’s Pawn is present. These types of opening positions boosted my chess understanding and helped me advance to the top. My method of explaining the evolution in thinking about the IQP is to trace the history of games with the Tarrasch Defence, from Siegbert Tarrasch himself to Garry Kasparov. The recommended theory moves may have changed in the 21st century, but there are many positional ideas that can best be understood by studying “ancient” games. Some readers may find this book answers their questions about which openings to play, how to properly use computer evaluations, and so on. However, the aim of this book is not to give readymade answers – I will not ask you to memorize that on move 23 of a certain line you must play ¤d5. In chess, the ability to analyse and arrive at the right conclusions yourself is the most valuable skill. I hope that every chess player and coach who reads this book will develop his or her understanding of opening preparation. -

Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW!

U.S. TEAM TAKES GOLD AT THE WORLD SENIOR October 2018 | USChess.org Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW! GM Alexander Kalinin traces Fabiano Caruana’s career, analyses the role of his various trainers, explains the development of his playing style and points out what you can learn from his best games. With #!"$ paperback | 208 pages | $19.95 | from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDs at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum - Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked ADULT $ SCHOLASTIC $ 1 YEAR 49 1 YEAR 25 PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP In addition to these two MEMBER BENEFITS premium categories, US Chess has many •Rated Play for the US Chess community other categories and multi-year memberships •Print and digital copies of Chess Life (or Chess Life Kids) to suit your needs. For all of your options, •Promotional discounts on chess books and equipment see new.uschess.org/join- uschess/ or call •Helping US Chess grow the game 1-800-903-8723, option 4. www.uschess.org 1 Main office: Crossville, TN (931) 787-1234 Press and Communications Inquiries: [email protected] Advertising inquiries: (931) 787-1234, ext. 123 Tournament Life Announcements (TLAs): All TLAs should be e-mailed to [email protected] or sent to P.O. Box 3967, Crossville, TN 38557-3967 Letters to the editor: Please submit to [email protected] Receiving Chess Life: To receive Chess Life as a Premium Member, join US Chess, or enter a US Chess tournament, go to uschess.org or call 1-800-903-USCF (8723) Change of address: Please send to [email protected] Other inquiries: [email protected], (931) 787-1234, fax (931) 787-1200 US CHESS US CHESS STAFF EXECUTIVE Executive Director, Carol Meyer ext. -

Positional Attacks

Positional Attacks Joel Johnson Edited by: Patrick Hammond © Joel Johnson, January 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from Joel Johnson. Edited by: Patrick Hammond Cover Photography: Barry M. Evans Cover Design and Proofreading: Joel Johnson Game Searching: Joel Johnson, Richard J. Cowan, William Parker, Nick Desmarais Game Contributors: Brian Wall, Jack Young, Clyde Nakamura, James Rizzitano, Keith Hayward, Hal Terrie, Richard Cowan, Jesús Seoane, William Parker, Domingos Perego, Danielle Rice Linares Diagram and Linares Figurine fonts ©1993-2003 by Alpine Electronics, Steve Smith Alpine Electronics 703 Ivinson Ave. Laramie, WY 82070 Email: Alpine Chess Fonts ([email protected]) Website: http://www.partae.com/fonts/ Pressure Gauge graphic Image Copyright Araminta, 2012 Used under license from Shutterstock.com In Memoriam to my step dad and World War II Navy, Purple Heart Recipient, Theodore Kosiavelon, 12/22/1921 – 11/09/2012 CONTENTS Preface 7 Kudos 7 Brian Wall 8 Young Rising Stars 27 Daniil Dubov 27 Wei Yi 30 Section A – Pawn Roles 36 Pawn Structure 37 Ugliest Pawn Structure Ever? 38 Anchoring 41 Alien Pawn 48 Pawn Lever 63 Pawn Break 72 Center Pawn Mass 75 Isolated Pawn 94 Black Strategy 95 White Strategy 96 Eliminate the Isolated Pawn Weakness with d4-d5 96 Sacrifices on e6 & f7 , Often with f2-f4-f5 Played 99 Rook Lift Attack 104 Queenside Play 111 This Is Not Just -

Chess Book List

A treat for you all to start the New Year. Happy New Year to you all and I hope some of these books make you better chess players. Here is the next book list I told you about a few weeks ago. All are books on the Opening. All prices are in Canadian funds and postage will be added to your order. Any payment method is acceptable but please note that if you wish to use your credit card you can do so via PayPal. To do this I will send an invoice to you and you will follow the instructions sent to you from PayPal. Paying this way is quick and easy but it will cost you 4% more. This is the fee Paypal charges me for using their services. A personal cheque or money order will not cost you anything more than the actual book costs plus postage. As always first come-first served so if you see something you want please order promptly to avoid disappointment. If you ordered something from the first list I will combine shipping to save you some postage. Please note that # 1 to # 134 have been already offered and sent to all CCCA members during January. If you have email and did not receive these messages it is because I do not have your address or the address I have on file for you is no longer functioning. I suggest you contact me so I can correct this situation. My email is [email protected]. Please note that I added # 135 to 150 just so you email members can have something new to look at. -

Chess & Bridge

2013 Catalogue Chess & Bridge Plus Backgammon Poker and other traditional games cbcat2013_p02_contents_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:18 Page 1 Contents CONTENTS WAYS TO ORDER Chess Section Call our Order Line 3-9 Wooden Chess Sets 10-11 Wooden Chess Boards 020 7288 1305 or 12 Chess Boxes 13 Chess Tables 020 7486 7015 14-17 Wooden Chess Combinations 9.30am-6pm Monday - Saturday 18 Miscellaneous Sets 11am - 5pm Sundays 19 Decorative & Themed Chess Sets 20-21 Travel Sets 22 Giant Chess Sets Shop online 23-25 Chess Clocks www.chess.co.uk/shop 26-28 Plastic Chess Sets & Combinations or 29 Demonstration Chess Boards www.bridgeshop.com 30-31 Stationery, Medals & Trophies 32 Chess T-Shirts 33-37 Chess DVDs Post the order form to: 38-39 Chess Software: Playing Programs 40 Chess Software: ChessBase 12` Chess & Bridge 41-43 Chess Software: Fritz Media System 44 Baker Street 44-45 Chess Software: from Chess Assistant 46 Recommendations for Junior Players London, W1U 7RT 47 Subscribe to Chess Magazine 48-49 Order Form 50 Subscribe to BRIDGE Magazine REASONS TO SHOP ONLINE 51 Recommendations for Junior Players - New items added each and every week 52-55 Chess Computers - Many more items online 56-60 Bargain Chess Books 61-66 Chess Books - Larger and alternative images for most items - Full descriptions of each item Bridge Section - Exclusive website offers on selected items 68 Bridge Tables & Cloths 69-70 Bridge Equipment - Pay securely via Debit/Credit Card or PayPal 71-72 Bridge Software: Playing Programs 73 Bridge Software: Instructional 74-77 Decorative Playing Cards 78-83 Gift Ideas & Bridge DVDs 84-86 Bargain Bridge Books 87 Recommended Bridge Books 88-89 Bridge Books by Subject 90-91 Backgammon 92 Go 93 Poker 94 Other Games 95 Website Information 96 Retail shop information page 2 TO ORDER 020 7288 1305 or 020 7486 7015 cbcat2013_p03to5_woodsets_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:53 Page 1 Wooden Chess Sets A LITTLE MORE INFORMATION ABOUT OUR CHESS SETS..