The Odessa Massacre and Its Perpetrators: Memory And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1972-1973

Eastern Progress Eastern Progress 1972-1973 Eastern Kentucky University Year 1973 Eastern Progress - 12 Apr 1973 Eastern Kentucky University This paper is posted at Encompass. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress 1972-73/26 r » r r Elections To Be Held Wednesday Four Candidates Vie For Student Association Presidential Position there we can gel it up here," Kelley—Hughes in dormitories, Kelley and Peters—Clay He also feels that there should Slade—Rowland they planned lo use the Gray—Vaughn Gray continued. Hughes see a realistic fee for be open visitation during the Progress in a controlled students, payable at weekend with hours being,"say, Steve Slade, a junior from manner, Rowland was quick lo However, Miss Vaughn and The second set of candidates "Government is to listen to its Gray do not feel that everyone for office are Bob Kelley, a registration for (he ser- Cynthiana, and Steve Rowland, explain. Gary Gray, sophomore from constituency and do those "I would have no...uh not should live off campus. "Let senior broadcasting major from vice.' a junior from Louisville are the Royal Oak, Michigan, and Carla things which the constituency even try to have any influence freshmen live in the dorm one Cincinnati, Ohio, and Bill A "realistic policy of open fourth pair of candidates to seek Vaughn, sophomore from wants it to do," said Dave over the Progress. If you have year...so they can mature just a Hughes, a junior pre-med major visitation" is also on the plat- the offices of president and vice- Middlesboro, are Ihe first two form. -

Hate Crime Report 031008

HATE CRIMES IN THE OSCE REGION -INCIDENTS AND RESPONSES ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2007 Warsaw, October 2008 Foreword In 2007, violent manifestations of intolerance continued to take place across the OSCE region. Such acts, although targeting individuals, affected entire communities and instilled fear among victims and members of their communities. The destabilizing effect of hate crimes and the potential for such crimes and incidents to threaten the security of individuals and societal cohesion – by giving rise to wider-scale conflict and violence – was acknowledged in the decision on tolerance and non-discrimination adopted by the OSCE Ministerial Council in Madrid in November 2007.1 The development of this report is based on the task the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) received “to serve as a collection point for information and statistics on hate crimes and relevant legislation provided by participating States and to make this information publicly available through … its report on Challenges and Responses to Hate-Motivated Incidents in the OSCE Region”.2 A comprehensive consultation process with governments and civil society takes place during the drafting of the report. In February 2008, ODIHR issued a first call to the nominated national points of contact on combating hate crime, to civil society, and to OSCE institutions and field operations to submit information for this report. The requested information included updates on legislative developments, data on hate crimes and incidents, as well as practical initiatives for combating hate crime. I am pleased to note that the national points of contact provided ODIHR with information and updates on a more systematic basis. -

Indices of the Comparative Civilizations Review, No. 1-83

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 84 Number 84 Spring 2021 Article 14 2021 Indices of the Comparative Civilizations Review, No. 1-83 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation (2021) "Indices of the Comparative Civilizations Review, No. 1-83," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 84 : No. 84 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol84/iss84/14 This End Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. et al.: Indices of the <i>Comparative Civilizations Review</i>, No. 1-83 Comparative Civilizations Review 139 Indices of the Comparative Civilizations Review, No. 1-83 A full history of the origins of the Comparative Civilizations Review may be found in Michael Palencia-Roth’s (2006) "Bibliographical History and Indices of the Comparative Civilizations Review, 1-50." (Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 54: Pages 79 to 127.) The current indices to CCR will exist as an article in the hardcopy publication, as an article in the online version of CCR, and online as a separate searchable document accessed from the CCR website. The popularity of CCR papers will wax and wane with time, but as of September 14, 2020, these were the ten most-popular, based on the average number of full-text downloads per day since the paper was posted. -

STATEMENT on UNIDENTIFIED FLYING OBJECTS Submitted to The

INTRODUCTION:.................................................................................................................................................................. 1 SCOPE AND BACKGROUND OF PRESENT COMMENTS:........................................................................................ 2 THE UNCONVENTIONAL NATURE OF THE UFO PROBLEM:................................................................................ 3 SOME ALTERNATIVE HYPOTHESES:............................................................................................................................. 3 SOME REMARKS ON INTERVIEWING EXPERIENCE AND TYPES OF UFO CASES ENCOUNTERED:....... 5 WHY DON'T PILOTS SEE UFOs?....................................................................................................................................10 WHY ARE UFOs ONLY SEEN BY LONE INDIVIDUALS, WHY NO MULTIPLE-WITNESS SIGHTINGS? .....16 WHY AREN'T UFOs EVER SEEN IN CITIES? WHY JUST IN OUT-OF-THE-WAY PLACES?...........................22 WHY DON'T ASTRONOMERS EVER SEE UFOs? .......................................................................................................27 METEOROLOGISTS AND WEATHER OBSERVERS LOOK AT THE SKIES FREQUENTLY. WHY DON'T THEY SEE UFOs?................................................................................................................................................................30 DON'T WEATHER BALLOONS AND RESEARCH BALLOONS ACCOUNT FOR MANY UFOs?......................34 WHY AREN'T UFOs EVER TRACKED BY RADAR?....................................................................................................38 -

Forensic Psychology FORS 2450 • Fall 2014

• Forensic Psychology FORS 2450 • Fall 2014 Syllabus Name: Shawndee Kennedy E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 432-335-6455 Office: ET 159 Office Hours Campus Office Hours: Monday: 2-5pm Tuesday: 2-5pm Wednesday: 1-4 pm Thursday: By appointment only Friday: 9-10am Online Office Hours: Same as above About Your Instructor I have spent my career working in criminal investigations and testifying as an expert witness in criminal and civil trials. I was a forensic interviewer before coming to Odessa College. I interviewed child victims of sexual and physical abuse, those who witnessed violent crimes such as murder, suicide or domestic violence, and mentally handicapped adults. I also testified as an expert witness in the areas of child abuse, child sexual abuse, the disclosure process, delayed outcries in abuse cases and memory and suggestibility of child victims. I worked with federal and local law enforcement, child protective services, prosecutors, nurses, mental health professionals and advocates to help give abuse victims a voice. Preferred Method of Communication: I prefer to be contacted via email or text since I am in class most of the time. If you email and I do not respond please text or call me, as your email may have been sent to my junk folder. Expectations for Engagement for Instructor: As an instructor, I understand the importance of clear, timely communication with my students. In order to maintain sufficient communication, I will • provide my contact information at the beginning of the syllabus; • respond to all messages within 24 hours if received Monday through Thursday, and within 48 hours if received Friday through Sunday; and, • notify students of any extended times that I will be unavailable and provide them with alternative contact information (for me or for my supervisor) in case of during the time I am unavailable. -

Year 2 Volume 3/ 2015

Cultural Intertexts Year 2 Volume 3/ 2015 Cultural Intertexts Journal of Literature, Cultural Studies and Linguistics published under the aegis of: Faculty of Letters – Department of English Research Centre Interface Research of the Original and Translated Text. Cognitive and Communicative Dimensions of the Message Doctoral School of Socio-Humanities Editing Team Editor-in-Chief: Michaela PRAISLER ([email protected]) Editorial Board Oana-Celia GHEORGHIU ([email protected] ) Alexandru PRAISLER ([email protected]) Andreea IONESCU ([email protected]) Irina RAȚĂ ([email protected]) Editorial Secretary Mihaela IFRIM ([email protected]) ISSN-L 2393-0624 ISSN 2393-0624 E-ISSN 2393-1078 Full content available at cultural-intertexts.webnode.com/ © 2015 Casa Cărții de Știință Cluj- Napoca, B-dul Eroilor 6-8 www.casacartii.ro [email protected] SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Professor Ioana MOHOR-IVAN, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Professor Vladislava GORDIC PETKOVIC, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Professor Anca DOBRINESCU, ”Petrol și Gaze” University of Ploiești Associate Professor Ruxanda BONTILĂ, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Steluţa STAN, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Gabriela COLIPCĂ-CIOBANU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Senior Lecturer Cătălina NECULAI, Coventry University, UK Senior Lecturer Nicoleta CINPOEȘ, University of Worcester, UK Senior Lecturer Isabela MERILĂ, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi * The contributors are solely responsible for the scientific accuracy of their articles. TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITOR’S NOTE 5 LITERATURE AS WORLD INTERTEXT(S) Gabriela-Iuliana COLIPCĂ-CIOBANU 6 Shakespeare, the Musical and Political Humour in Kiss Me Kate Revived Daniela-Irina DARIE 32 The Tragedies of Yorùbá’s Spiritual Space Oana-Celia GHEORGHIU, Michaela PRAISLER 42 Western Political Philosophy in J. -

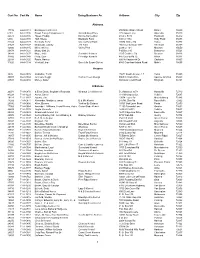

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Person's Name Plumber Or ACR License Number License Type

Person's Name Plumber or ACR License Number License Type RRC License Number Licensee Name Licensee Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City State Zip County Licensee Phone Alternate Address Line 1 Line 2 City State Zip County Phone ABBOTT, CHRISTOPHER WAYNE AC23153 ACR CONTRACTOR HOME MAINTENACE SERVICE 2110 FM 999 GARY TX 75643 PANOLA ABBOTT, GEORGE WESLEY J-29427 PLUMBER PO BOX 236 TERLINGUA TX 79852 BREWSTER 000-000-0000 ABREGO, ELISEO JR M-19518 PLUMBER J'S PLUMBING PO BOX 3218 EDINBURG TX 78541 ABREGO, RODOLFO M J-31361 PLUMBER J'S PLUMBING PO BOX 3218 EDINBURG TX 78541 ABREGO, RUBEN JAIME J-36253 PLUMBER J'S PLUMBING PO BOX 3218 EDINBURG TX 78540 ABSHER, MICHAEL TODD M-39342 PLUMBER BEARCAT PLUMBING PO BOX 1747 ALEDO TX 76008 PARKER 817-300-3228 ACKERMANN, INGOMAR KURT TACLA10472E ACR CONTRACTOR ACKERMANN AIR SERVICES 4717 SUNSET CIRCLE S. KELLER TX 76244 TARRANT 817-562-4446 ACKERMANN, JOHN ROGER RMP-40188 PLUMBER ACKERMANN PLUMBING CO 301 E 4TH ST KEENE TX 76059 JOHNSON 817-558-8878 ACKLEY, EARL WILSON J-38212 PLUMBER 14350 CURL'S PLUMBING CO. P.O. BOX 1340 RED OAK TX 75154 ELLIS 972-617-0090 121 HAWK LN. RED OAK TX 75154 ELLIS ACTON, PHILIP ANDREW TACLB17818E ACR CONTRACTOR BAND-AIRE LLC P.O. BOX 2576 BANDERA TX 78003 BANDERA 830-796-9111 ACUNA, MARK ANTHONY J-28268 PLUMBER MURRAY PLUMBING 4430 CENTER GATE SAN ANTONIO TX 78217 BEXAR 210-277-7177 ADAIR, TIMOTHY MICHAEL ACLB26433E ACR CONTRACTOR WEATHERFORD ISD 907 S ELM ST. WEATHERFORD TX 76086 PARKER 817-598-2853 ADAME, ANTONIO J-47567 PLUMBER 13850 DIPLOMAT DRIVE DALLAS TX 75234 DALLAS ADAME, JAIME G. -

Hearing on Anti-Semitism: a Growing Threat to All Faiths

Hearing on Anti-Semitism: A Growing Threat to All Faiths House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Testimony of Andrew Srulevitch, European Affairs Director Anti-Defamation League February 27, 2013 Washington, DC Let me offer special thanks on behalf of the Anti-Defamation League and its National Director, Abraham Foxman, to Chairman Smith and all the Members of the Subcommittee for holding this hearing today and for the many hearings, letters, and rallying cries that have kept this issue front and center. Your commitment to the fight against anti-Semitism and your determination to move from concern to action inspires and energizes all of us. The history of the Jewish people is fraught with examples of the worst violations of human rights - forced conversions, expulsions, inquisitions, pogroms, and genocide. The struggle against the persecution of Jews was a touchstone for the creation of some of the foundational human rights instruments and treaties as well as the development of important regional human rights mechanisms like the human dimension commitments of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). We focus today on anti-Semitism but we are mindful that, in advancing the fight against anti- Semitism, we elevate the duty of governments to comply with broader human rights commitments and norms. That is the core of ADL’s mission: to secure justice and fair treatment for Jews in tandem with safeguarding the rights of all groups. Anti-Semitism is a primary concern for the Anti-Defamation League – not just because we are a Jewish community organization, but because anti-Semitism, the oldest and most persistent form of prejudice, threatens security and democracy, and poisons the health of a society as a whole. -

1981-1982 Academic Catalog

I I I Contents I Learning Lasts A Lifetime 3 I Calendar 10 Instructional Programs 13 I Admissions 119 Financial Information 123 I Student Services 127 Academic Information 132 I Degrees 141 College Staff 144 I Index 154 I Map 157 Volume Thirty-five Spring 1981 I I I Information and regulations printed in this catalog are I subject to change. The Board of Trustees and the administrative staff may revise programs, courses, tuition, I fees, or any other information stated in this catalog. Odessa College Bulletin Published March, April, May, and November by Odessa College, 201 W. University, Odessa, Texas, 79762. I Second-Class Postage paid at Odessa, Texas. Publication Number: 468190. Postmaster: Send address changes to Odessa College, I 201 W. University, Odessa, Texas, 79762. Photos by Brent Cavanaugh Phone 915 337-5381 I I I I I J· I Learning Lasts A Lifetime "If a man empties his purse into his head, no man can take it away from him. An investment in knowledge always pays the best interest." - Benjamin Franklin I 7 I Learning from the Past Odessa College's past is interwoven A wide variety of university-preparatory with growth and progress. A review of courses also is offered for students I the college's history reveals a success planning to finish four-year degrees at story of a public institution that has senior colleges or universities. maintained the community college spirit Odessa College is a mature college I and has grown by serving the people of with a youthful spirit. The college is Ector County and the Permian Basin. -

FINAL REPORT International Commission on the Holocaust In

FINAL REPORT of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania Presented to Romanian President Ion Iliescu November 11, 2004 Bucharest, Romania NOTE: The English text of this Report is currently in preparation for publication. © International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. All rights reserved. DISTORTION, NEGATIONISM, AND MINIMALIZATION OF THE HOLOCAUST IN POSTWAR ROMANIA Introduction This chapter reviews and analyzes the different forms of Holocaust distortion, denial, and minimalization in post-World War II Romania. It must be emphasized from the start that the analysis is based on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s definition of the Holocaust, which Commission members accepted as authoritative soon after the Commission was established. This definition1 does not leave room for doubt about the state-organized participation of Romania in the genocide against the Jews, since during the Second World War, Romania was among those allies and a collaborators of Nazi Germany that had a systematic plan for the persecution and annihilation of the Jewish population living on territories under their unmitigated control. In Romania’s specific case, an additional “target-population” subjected to or destined for genocide was the Romany minority. This chapter will employ an adequate conceptualization, using both updated recent studies on the Holocaust in general and new interpretations concerning this genocide in particular. Insofar as the employed conceptualization is concerned, two terminological clarifications are in order. First, “distortion” refers to attempts to use historical research on the dimensions and significance of the Holocaust either to diminish its significance or to serve political and propagandistic purposes. Although its use is not strictly confined to the Communist era, the term “distortion” is generally employed in reference to that period, during which historical research was completely subjected to controls by the Communist Party’s political censorship. -

La Migración Judía Hacia Tandil (1880 - 1945)

XIV Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, 2013. La migración judía hacia Tandil (1880 - 1945). Leonardo Brunelli. Cita: Leonardo Brunelli (2013). La migración judía hacia Tandil (1880 - 1945). XIV Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-010/453 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Colonia Rusa, una experiencia de colonizacin austral en la "nueva" Argentina (1906 - 1960) Leonardo Brunelli FCH-UNCPBA / Dpt. de Historia DNI 26 966 262 leolenfer yahoo.com.ar bjetivos: Para reali%ar este trabajo me centrar( en el an)lisis de una colonia de emigrados jud+os, conocida como Colonia Rusa en las cercan+as de -eneral .oca. El objeti0o principal es anali%ar la relaci1n de a2uel grupo de inmigrantes en el marco de las relaciones e integraci1n 2ue se crearon entre ellos e inmigrantes de otras colecti0idades 3principalmente espa4oles, alemanes e italianos6, as+ como su relaci1n con grupos criollos. La solidaridad fue el cimiento sobre la 2ue construyeron sus 0i0iendas, labraron la tierra y educaron a sus hijos, respetando sus tradiciones, pero inculc)ndoles a su 0e% la cultura nacional y form)ndolos en las aulas de la escuela p7blica.