Digital Ecosystem Research Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

ONLINE INCIVILITY and ABUSE in CANADIAN POLITICS Chris

ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS Chris Tenove Heidi Tworek TROLLED ON THE CAMPAIGN TRAIL ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS CHRIS TENOVE • HEIDI TWOREK COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2020 Chris Tenove; Heidi Tworek; Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. CITATION Tenove, Chris, and Heidi Tworek (2020) Trolled on the Campaign Trail: Online Incivility and Abuse in Canadian Politics. Vancouver: Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. CONTACT DETAILS Chris Tenove, [email protected] (Corresponding author) Heidi Tworek, [email protected] CONTENTS AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES ..................................................................................................................1 RESEARCHERS ...............................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................5 FACING INCIVILITY IN #ELXN43 ....................................................................................................8 -

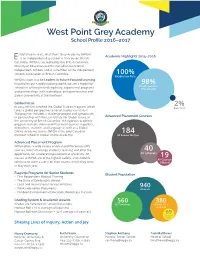

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017 stablished in 1996, West Point Grey Academy (WPGA) Academic Highlights 2015–2016 E is an independent day school in Vancouver, British Columbia. WPGA is accredited by the British Columbia Ministry of Education and the Canadian Accredited Independent Schools and is a member of the Independent Schools Association of British Columbia. raduation Rate WPGA’s vision is to be Leaders in Future-Focused Learning. Inspired by our rapidly evolving world, we are a model for ostsecondary schools in offering interdisciplinary, experiential programs lacements and partnerships, with technology, entrepreneurship and global connectivity at the forefront. Global Focus In 2014, WPGA launched the Global Studies Program, which ap ear takes a global perspective to social studies curriculum. The program includes a challenge project and symposium in partnership with the Liu Institute for Global Issues at Advanced Placement Courses the University of British Columbia; the rigorous academic program includes Advanced Placement courses in politics, economics, statistics and language as well as a Global Online Academy course (WPGA is the only Canadian 184 member school in Global Online Academy). A ams ritten Advanced Placement Program WPGA offers a wide variety of Advanced Placement (AP) courses, which challenge students’ learning and offer the 40 opportunity for accelerated placement at university. AP A Scholars classes at WPGA are of the highest calibre, and students continue to score a 4 or 5 on their exams, which they write in May each year. Flagship Programs for Senior Students Student Population • First Responders Medical Training • The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award • Local and International Service Initiatives • Work Experience Placements Students • Outdoor Environmental Education; Wilderness Pursuits Grading System & Academic Awards 560 380 Grades are reflected on school transcripts. -

Claimant's Memorial on Merits and Damages

Public Version INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR ICSID Case No. ARB/16/16 SETTLEMENT OF INVESTMENT DISPUTES BETWEEN GLOBAL TELECOM HOLDING S.A.E. Claimant and GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Respondent CLAIMANT’S MEMORIAL ON THE MERITS AND DAMAGES 29 September 2017 GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP Telephone House 2-4 Temple Avenue London EC4Y 0HB United Kingdom GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP 200 Park Avenue New York, NY 10166 United States of America Public Version TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 II. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 3 III. Canada’s Wireless Telecommunications Market And Framework For The 2008 AWS Auction................................................................................................................................. 17 A. Overview Of Canada’s Wireless Telecommunications Market Leading Up To The 2008 AWS Auction.............................................................................................. 17 1. Introduction to Wireless Telecommunications .................................................. 17 2. Canada’s Wireless Telecommunications Market At The Time Of The 2008 AWS Auction ............................................................................................ 20 B. The 2008 AWS Auction Framework And Its Key Conditions ................................... 23 1. The Terms Of The AWS Auction Consultation -

SFU Thesis Template Files

The Right to Authentic Political Communication by Ann Elizabeth Rees M.A., Simon Fraser University, 2005 B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1980 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Arts and Social Science Ann Elizabeth Rees 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 Approval Name: Ann Elizabeth Rees Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: The Right to Authentic Political Communication Examining Committee: Chair: Katherine Reilly, Assistant Professor Peter Anderson Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Catherine Murray Supervisor Professor Alison Beale Supervisor Professor Andrew Heard Internal Examiner Associate Professor Political Science Department Paul Thomas External Examiner Professor Emeritus Department of Political Studies University of Manitoba Date Defended/Approved: January 22, 2016 ii Abstract Increasingly, governments communicate strategically with the public for political advantage, seeking as Christopher Hood describes it to “avoid blame” and “claim credit” for the actions and decisions of governance. In particular, Strategic Political Communication (SPC) is becoming the dominant form of political communication between Canada’s executive branch of government and the public, both during elections and as part of a “permanent campaign” to gain and maintain public support as means to political power. This dissertation argues that SPC techniques interfere with the public’s ability to know how they are governed, and therefore undermines the central right of citizens in a democracy to legitimate elected representation by scrutinizing government and holding it to account. Realization of that right depends on an authentic political communication process that provides citizens with an understanding of government. By seeking to hide or downplay blameworthy actions, SPC undermines the legitimation role public discourse plays in a democracy. -

Shuffle Fallout Harper's Ministry Canada's North

CANADA’S HARPER’S SHUFFLE NORTH MINISTRY FALLOUT The Hill Times’ extensive policy Get all you need to know about PM Post-shuffle, Tory staffers are upset briefing on Canada’s North. p. 15-29 Harper’s shuffle. p. 1, 3, 4, 6, 10 with the PMO’s HR management. p. 34 EIGHTEENTH YEAR, NO. 901 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, AUGUST 20, 2007 $4.00 Harper’s MacKay and Cabinet shuffle Bernier the plays well in new stars of Quebec, says Cabinet, but new poll did MacKay get Of all the moves, Chuck promotion? Strahl’s jump into indian and northern affairs is seen least ‘If MacKay doesn’t carry Afghani- favourably by the public stan, defence and so on, and shore up some support in Atlan- By BEA VONGDOUANGCHANH tic Canada, Harper fails. And I The Conservatives made suspect Harper...has figured that inroads in Quebec with its Cabinet out,’ says Prof. Donald Savoie shuffle last Tuesday, according to a new poll by Innovative Research Group for The Hill Times, which By CHRISTOPHER GULY shows that, as a result of the shuf- Photograph by Jake Wright, The Hill Times fle, Quebecers are twice as likely Cabinet shuffle time should be happy time, people: From left to right: Indian and Northern Affairs Minister Chuck Peter MacKay and Maxime Ber- to be more favourable to the gov- Strahl, Defence Minister Peter MacKay, National Revenue Minister Gordon O’Connor, International Cooperation nier—the young, handsome, telege- ernment than the rest of Canada. Minister Bev Oda, Industry Minister Jim Prentice, and Foreign Affairs Minister Maxime Bernier. -

2019 BCSS AGM Package 2!.Pdf

April 26th - 27th, 2019 BCWhistler, SCHOOL British Columbia SPORTS Annual General Meeting Kelowna, British Columbia MEETING PACKAGE 2 April 2019 The Cove Lakeside Resort Kelowna, BC General Information The Cove Lakeside Resort - West Kelowna Hotel Information The Cove Lakeside Resort is located on the western shore of Okanagan Lake. The Resort features elegantly decorated rooms, stunning views and comfortable in-room amenities. If you have booked a room through BCSS, you will have received a confi rmation email from Karen Hum, please check to make sure the reservation information is correct. Things to do in Kelowna • Visit a Winery - Quail’s Gate Winery & Mission Hill Family Estate Winery are a short distance to from the hotel • Visit Bear Creek Provincial Park - A beautiful Provincial Park on the west side of Okanagan Lake • Relax at Lake Okanagan - Can you spot the Ogopogo? • Enjoy a Round of Golf - Test your skills at one of Kelowna’s 19 exceptional courses • Shopping - Kelowna’s downtown shopping core has a blend of retail shops, galleries, and boutiques to explore. Transportation The Cove Lakeside Resort is located at: 4205 Gellatly Road West Kelowna, BC V4T 2K2 Airport Kelowna International Airport has frequent fl ights in and out daily from around the province. It is a short trip from the Airport to the Resort. If you will be fl ying in to the AGM please let us know and we can help with arrangements for transportation to the hotel. Distance to and from the airport is 29km and approximately 25-40 minutes. Kelowna Weather Kelowna’s weather this time of year ranges from: Average Daily High: 15°C Average Daily Low: 3°C Please keep an eye on the weather closer to the AGM, and pack accordingly. -

2019 Federal Election: Result and Analysis

2019 Federal Election: Result and Analysis O C T O B E R 22, 2 0 1 9 NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS 157 121 24 3 32 (-20) (+26) (-15) (+1) (+22) Comparison between results reflected based on party standings at dissolution of the 42nd parliament • The Liberal Party of Canada (LPC) won a second mandate, although was diminished to minority status. • The result of the 43rd Canadian election is one of the closest in recent memory, with both the Liberals and Conservatives separated by little more than one percentage point. Conservatives share of vote is slightly higher than the Liberals, making major gains in key areas for the party • Bloc Quebecois (BQ) is a winner in this election, moving up to official party status which will give the party added resources as well as significance in the House of Commons • The NDP managed to win enough seats to potentially play an important role in the House of Commons, but the party took a big hit in Quebec — where they were only able to hold one of the Layton era “Orange Wave” seats • Maxime Bernier, who started the People’s Party of Canada after narrowly losing the Conservative leadership contest in 2017, lost the seat he has held onto since 2006 • The former Treasury Board president Dr. Jane Philpott, who ran as an independent following her departure from the liberal caucus, lost her seat in Markham Stouffville to former Liberal MPP and Ontario Minister of Health, Dr. Helena Jaczek. Jody Wilson-Raybould won as an independent in Vancouver Granville NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS 10 2 32 3 39 24 PARTY STANDINGS AT -

ISEA Championships Results

ISEA BC May 22, 2018 OFFICIAL MEET REPORT printed: 2018-05-22 8:27 PM RESULTS #6 Girls 60 Meters (4th Grade A) Pl Name Team Time Note H(Pl) Pts 1 JIANG, Selina Southridge School 9.71 (NW) 2(1) 10 2 WANG, Ann West Point Grey Academy 9.77 (NW) 1(1) 8 3 JEKUBIK, Emily York House School 9.86 (NW) 1(2) 6 4 WAN, Chloe Stratford Hall School 10.33 (NW) 2(2) 5 5 WESTERINGH, Eva Southpointe Academy 10.34 (NW) 2(3) 4 6 MCDONALD, Kate Crofton House School 10.38 (NW) 1(3) 3 7 ALEKSON, Lauren BPS 10.63 (NW) 2(4) 2 8 LINTS, Emily St. John's School 10.88 (NW) 1(4) 1 9 COHEN, Joelle Collingwood School 11.14 (NW) 1(5) 10 ZHOU, Jasmine Meadowridge School 11.59 (NW) 2(5) 11 SHU, Sophie Urban Academy Lions 13.10 (NW) 2(6) SECTION RESULTS Pl Name Team Time Note Section 1 of 2 Wind: (NW) 1 WANG, Ann West Point Grey Academy 9.77 2 JEKUBIK, Emily York House School 9.86 3 MCDONALD, Kate Crofton House School 10.38 4 LINTS, Emily St. John's School 10.88 5 COHEN, Joelle Collingwood School 11.14 Section 2 of 2 Wind: (NW) 1 JIANG, Selina Southridge School 9.71 2 WAN, Chloe Stratford Hall School 10.33 3 WESTERINGH, Eva Southpointe Academy 10.34 4 ALEKSON, Lauren BPS 10.63 5 ZHOU, Jasmine Meadowridge School 11.59 6 SHU, Sophie Urban Academy Lions 13.10 #7 Girls 60 Meters (4th Grade B) Pl Name Team Time Note H(Pl) Pts 1 MILAU, Rachel West Point Grey Academy 9.33 (NW) 2(1) 10 2 HU, Elgina Southridge School 10.02 (NW) 1(1) 8 3 CHAN, Olivia Crofton House School 10.38 (NW) 2(2) 6 4 STEWART, Campbell BPS 10.57 (NW) 1(2) 5 5 SOON, Makaella Stratford Hall School 10.64 (NW) 1(3) 4 6 HERAS , Emma Southpointe Academy 10.71 (NW) 1(4) 3 7 GORDON, Grace York House School 10.76 (NW) 2(3) 2 8 HUTCHINSON, Cecilia Meadowridge School 10.82 (NW) 2(4) 1 9 HUANG, Eva St. -

Core 1..190 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 145 Ï NUMBER 003 Ï 3rd SESSION Ï 40th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, March 5, 2010 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 79 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, March 5, 2010 The House met at 10 a.m. Mr. Iacobucci will report to me on the proposed redactions. He will report on whether proposed redactions genuinely relate to information that would be injurious to Canada's national security, national defence or international interests. Prayers In the case of injurious information, he will report to me on whether the information or a summary of it can be disclosed, and Ï (1000) report on the form of disclosure or any conditions on disclosure. [English] Mr. Iacobucci will prepare a report, in both official languages, that POINTS OF ORDER I will table in this House. That report will include a description of his DOCUMENTS REGARDING AFGHAN DETAINEES methodology and general findings. Hon. Rob Nicholson (Minister of Justice and Attorney I am sure that all members of the House will join me in welcoming General of Canada, CPC): Mr. Speaker, I rise on a point of this independent, comprehensive review by such an eminent jurist. order related to a motion adopted by this House on December 10 relating to the access to documents. Hon. Ralph Goodale (Wascana, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, obviously from the perspective of the official opposition, we welcome the The government acknowledges that it is appropriate that decisions remarks that the Minister of Justice has just made. -

Canadian Muslim Voting Guide: Federal Election 2019

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Sociology Faculty Publications Sociology Fall 2019 Canadian Muslim Voting Guide: Federal Election 2019 Jasmin Zine Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Fatima Chakroun Wilfrid Laurier University Shifa Abbas Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/soci_faculty Part of the Islamic Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Zine, Jasmin; Chakroun, Fatima; and Abbas, Shifa, "Canadian Muslim Voting Guide: Federal Election 2019" (2019). Sociology Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholars.wlu.ca/soci_faculty/12 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PREPARED BY CANADIAN ISLAMOPHOBIA INDUSTRY RESEARCH PROJECT TABLE OF C ONTENTS Summary of Federal Party Grades 1 How to Use this Guide 1 Introduction 2 Muslim Canadian Voters 2 Key Issues 2 Key Issues 1 Alt-Right Groups & Islamophobia 1 Motion 103 4 Religious Freedom and Dress in Quebec (BILL 21 & BILL 62) 3 Immigration/Refugees 4 Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) Movement 5 Foreign Policy 4 Conclusion 4 References by Section 5 The Canadian Muslim Voting Guide is led by Dr. Jasmin Zine, Professor, Wilfrid Laurier University. This guide was made possible with support from Hassina Alizai, Ryan Anningson, Sahver Kuzucuoglu, Doaa Shalabi, Ryan Hopkins and Phillip Oddi. The guide was designed by Fatima Chakroun and Shifa Abba. PAGE 01 S UMMARY OF FEDERAL PARTY GRADES Grades: P – Pass; N - Needs Improvement; F – Fail. -

High School Race League - Vancouver FINALS 02/08/2019 GS Results

High School Race League - Vancouver FINALS 02/08/2019 GS Results Rank First Name Last Name Bib. School Grade Seed Rank Run 1 Run 2 Time Women / Ski 1 LAURA KEOGH 51 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 9 2 51.980 54.530 1:46.510 2 Kate Matson 42 Templeton Secondary 12 1.5 52.630 54.340 1:46.970 3 Maia Matson 50 Templeton Secondary 12 2.5 53.640 56.630 1:50.270 4 CATARINA KOLLMANSBERGER 60 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 12 4 57.480 1:01.790 1:59.270 5 Smera Gill 78 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 9 15 57.920 1:01.710 1:59.630 6 ISABEL SHAW 53 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 12 3 1:00.060 1:01.630 2:01.690 7 Rebecca Davies 43 Point Grey 11 1 59.750 1:02.200 2:01.950 8 Abby Hamilton 49 Point Grey 12 2 1:00.060 1:04.700 2:04.760 9 Georgia Phillips 192 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 10 1:00.190 1:04.640 2:04.830 10 ALLISON SHAN 64 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 12 5 1:00.870 1:05.170 2:06.040 11 Quinn Gumprich 39 Kitsilano Secondary 8 1 1:00.790 1:06.480 2:07.270 12 Paige Olynk 54 Point Grey 12 3 1:02.220 1:06.420 2:08.640 13 Zara Smith 55 West Point Grey Academy 9 3 1:03.300 1:06.970 2:10.270 14 Nicole Shew 65 Point Grey 9 6 1:04.210 1:07.630 2:11.840 15 ALLISON KEOGH 71 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 11 8 1:03.940 1:08.270 2:12.210 16 Dayne Lebans 57 Point Grey 12 4 1:05.970 1:06.980 2:12.950 17 PARIS SHAN 67 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 12 6 1:05.580 1:07.640 2:13.220 18 Mandy Donaldson 83 YORK HOUSE SCHOOL 8 20 1:02.460 1:11.830 2:14.290 19 Vitoria Murakami 45 St.