ONLINE INCIVILITY and ABUSE in CANADIAN POLITICS Chris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Debates of the House of Commons

43rd PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION House of Commons Debates Official Report (Hansard) Volume 150 No. 008 Friday, October 2, 2020 Speaker: The Honourable Anthony Rota CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 467 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, October 2, 2020 The House met at 10 a.m. dence that the judge in their case will enforce sexual assault laws fairly and accurately, as Parliament intended. Prayer [English] It has never been more critical that all of us who serve the public GOVERNMENT ORDERS are equipped with the right tools and understanding to ensure that everyone is treated with the respect and dignity that they deserve, ● (1005) no matter what their background or their experiences. This would [English] enhance the confidence of survivors of sexual assault and the Cana‐ dian public, more broadly, in our justice system. There is no room JUDGES ACT in our courts for harmful myths or stereotypes. Hon. David Lametti (Minister of Justice, Lib.) moved that Bill C-3, An Act to amend the Judges Act and the Criminal Code, be read the second time and referred to a committee. I know that our government's determination to tackle this prob‐ lem is shared by parliamentarians from across Canada and of all He said: Mr. Speaker, I am pleased to stand in support of Bill political persuasions. The bill before us today will help ensure that C-3, an act to amend the Judges Act and the Criminal Code, which those appointed to a superior court would undertake to participate is identical to former Bill C-5. -

Federal Politics

REPORT FEDERAL POLITICS st DATE FebruaryNUMÉRO1 DE, 2020 PROJET METHODOLOGY METHODOLOGY Web survey using computer-assisted Web interviewing (CAWI) technology. From January 29th to January 30th, 2020 1,501 Canadians, 18 years of age or older, randomly recruited from LEO’s online panel. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to age, gender, mother tongue and region in order to ensure a representative sample of the population. No margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample (Web panel in this case). However for comparative purposes, a probability sample of 1,501 respondents would have a margin of error of ±2.53%, 19 times out of 20. The research results presented here are in full compliance with the CRIC Public Opinion Research Standards and Disclosure Requirements. 2 METHODOLOGY Notes on Reading this Report The numbers presented have been rounded up. However, the numbers before rounding were used to calculate the sums presented and might therefore not correspond to the manual addition of these numbers. In this report, data in bold red characters indicate a significantly lower proportion than that of other respondents. Conversely, data in bold green characters indicate a significantly higher proportion that that of other respondents. A more detailed methodology is presented in the appendix. If you have questions about the data presented in this report, please contact Christian Bourque, Associate and Executive Vice-Present at the following e-mail address: [email protected] 3 FEDERAL VOTING INTENTIONS Q1A/Q1B. If FEDERAL elections were held today, for which political party would you be most likely to vote? Would it be for...? In the event a respondent had no opinion, the following prompting question was asked: Even if you have not yet made up your mind, for which of the following political parties would you be most likely to vote? Would it be for the .. -

Liberal Base 'Less Than Enthusiastic' As PM Trudeau Prepares to Defend

Big Canadian challenge: the world is changing in Health disruptive + powerful + policy transformative briefi ng ways, & we better get HOH pp. 13-31 a grip on it p. 12 p.2 Hill Climbers p.39 THIRTIETH YEAR, NO. 1602 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER MONDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2019 $5.00 News Liberals News Election 2019 News Foreign policy House sitting last Trudeau opportunity for Liberal base ‘less than ‘masterful’ at Trudeau Liberals soft power, to highlight enthusiastic’ as PM falling short on achievements, hard power, says control the Trudeau prepares to ex-diplomat agenda and the Rowswell message, says a defend four-year record BY PETER MAZEREEUW leading pollster rime Minister Justin Trudeau Phas shown himself to be one to ‘volatile electorate,’ of the best-ever Canadian leaders BY ABBAS RANA at projecting “soft power” on the world stage, but his government’s ith the Liberals and Con- lack of focus on “hard power” servatives running neck W is being called into question as and neck in public opinion polls, say Liberal insiders Canada sits in the crosshairs of the 13-week sitting of the House the world’s two superpowers, says is the last opportunity for the The federal Liberals are heading into the next election with some members of the a former longtime diplomat. Continued on page 35 base feeling upset that the party hasn’t recognized their eff orts, while it has given Continued on page 34 special treatment to a few people with friends in the PMO, say Liberal insiders. Prime News Cybercrime Minister News Canada-China relations Justin Trudeau will RCMP inundated be leading his party into Appointing a the October by cybercrime election to special envoy defend his reports, with government’s a chance for four-year little success in record before ‘moral suasion’ a volatile prosecution, electorate. -

Dealing with Crisis

Briefing on the New Parliament December 12, 2019 CONFIDENTIAL – FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY Regional Seat 8 6 ON largely Flip from NDP to Distribution static 33 36 Bloc Liberals pushed out 10 32 Minor changes in Battleground B.C. 16 Liberals lose the Maritimes Goodale 1 12 1 1 2 80 10 1 1 79 1 14 11 3 1 5 4 10 17 40 35 29 33 32 15 21 26 17 11 4 8 4 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 BC AB MB/SK ON QC AC Other 2 Seats in the House Other *As of December 5, 2019 3 Challenges & opportunities of minority government 4 Minority Parliament In a minority government, Trudeau and the Liberals face a unique set of challenges • Stable, for now • Campaign driven by consumer issues continues 5 Minority Parliament • Volatile and highly partisan • Scaled back agenda • The budget is key • Regulation instead of legislation • Advocacy more complicated • House committee wild cards • “Weaponized” Private Members’ Bills (PMBs) 6 Kitchen Table Issues and Other Priorities • Taxes • Affordability • Cost of Living • Healthcare Costs • Deficits • Climate Change • Indigenous Issues • Gender Equality 7 National Unity Prairies and the West Québéc 8 Federal Fiscal Outlook • Parliamentary Budget Officer’s most recent forecast has downgraded predicted growth for the economy • The Liberal platform costing projected adding $31.5 billion in new debt over the next four years 9 The Conservatives • Campaigned on cutting regulatory burden, review of “corporate welfare” • Mr. Scheer called a special caucus meeting on December 12 where he announced he was stepping -

Evidence of the Special Committee on the COVID

43rd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Special Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic EVIDENCE NUMBER 019 Tuesday, June 9, 2020 Chair: The Honourable Anthony Rota 1 Special Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic Tuesday, June 9, 2020 ● (1200) Mr. Paul Manly (Nanaimo—Ladysmith, GP): Thank you, [Translation] Madam Chair. The Acting Chair (Mrs. Alexandra Mendès (Brossard— It's an honour to present a petition for the residents and con‐ Saint-Lambert, Lib.)): I now call this meeting to order. stituents of Nanaimo—Ladysmith. Welcome to the 19th meeting of the Special Committee on the Yesterday was World Oceans Day. This petition calls upon the COVID-19 Pandemic. House of Commons to establish a permanent ban on crude oil [English] tankers on the west coast of Canada to protect B.C.'s fisheries, tourism, coastal communities and the natural ecosystems forever. I remind all members that in order to avoid issues with sound, members participating in person should not also be connected to the Thank you. video conference. For those of you who are joining via video con‐ ference, I would like to remind you that when speaking you should The Acting Chair (Mrs. Alexandra Mendès): Thank you very be on the same channel as the language you are speaking. much. [Translation] We now go to Mrs. Jansen. As usual, please address your remarks to the chair, and I will re‐ Mrs. Tamara Jansen (Cloverdale—Langley City, CPC): mind everyone that today's proceedings are televised. Thank you, Madam Chair. We will now proceed to ministerial announcements. I'm pleased to rise today to table a petition concerning con‐ [English] science rights for palliative care providers, organizations and all health care professionals. -

Chong Favoured in Conservative Leadership Contest

Chong Favoured in Conservative Leadership Contest Chong and Raitt favoured among party members, Half want “someone else" TORONTO December 8th – In a random sampling of public opinion taken by the Forum Poll among 1304 Canadian voters, Michael Chong leads preference for a Conservative leader among the general public (10%), followed by Lisa Raitt (8%), Michael Chong leads Kellie Leitch (7%), Chris Alexander (6%) and Maxime Bernier (5%) and Steve preference for a Blaney (5%). Andrew Scheer (3%) and Brad Trost (2%) have less support. Other Conservative leader candidates were excluded for brevity. among the general public It must be pointed out that fully half the sample opts for “someone else” (53%), (10%), followed by Lisa other than the 8 candidates listed. Raitt (8%), Kellie Leitch (7%), Chris Alexander (6%) Among Conservative voters, there is no clear favourite, and Chris Alexander (8%), and Maxime Bernier (5%) Steve Blaney (9%), Michael Chong (8%) and Lisa Raitt (8%) are evenly matched. and Steve Blaney (5%) One half choose “someone else”. “We are drawing closer to Among a very small sample of Conservative Party members (n=65), Raitt (12%) the Leadership and Chong (10%) are tied, and followed by Chris Alexander (9%) and Kellie Leitch Convention, and (8%). One half want “someone else” (48%). interested voters have had “We are drawing closer to the Leadership Convention, and interested voters have the chance to see two had the chance to see two debates now. Yet, Conservatives still haven’t seen the debates now. Yet, candidate they want, and one half won’t support any of the people running," said Conservatives still haven’t Forum Research President, Dr. -

Regular Council Meeting Minutes

REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES OCTOBER 2, 2012 A Regular Meeting of the Council of the City of Vancouver was held on Tuesday, October 2, 2012, at 9:41 am, in the Council Chamber, Third Floor, City Hall. PRESENT: Mayor Gregor Robertson Councillor George Affleck Councillor Elizabeth Ball Councillor Adriane Carr Councillor Heather Deal* Councillor Kerry Jang* Councillor Raymond Louie Councillor Geoff Meggs* Councillor Andrea Reimer Councillor Tim Stevenson Councillor Tony Tang CITY MANAGER’S OFFICE: Penny Ballem, City Manager CITY CLERK’S OFFICE: Janice MacKenzie, City Clerk Terri Burke, Meeting Coordinator * Denotes absence for a portion of the meeting. WELCOME The proceedings in the Council Chamber began with welcoming comments from Councillor Meggs. PROCLAMATION - Homelessness Action Week The Mayor proclaimed the week of October 7-13, 2012, as Homelessness Action Week in the city of Vancouver and invited the following individuals from At Home/Chez Soi to the podium to accept the proclamation and say a few words: Dr. Julian Somers Greg Richmond Emily Grant Regular Council Meeting Minutes, Tuesday, October 2, 2012 2 "IN CAMERA" MEETING MOVED by Councillor Deal SECONDED by Councillor Jang THAT Council will go into a meeting later this day, which is closed to the public, pursuant to Section 165.2(1) of the Vancouver Charter, to discuss matters related to paragraphs: (a) personal information about an identifiable individual who holds or is being considered for a position as an officer, employee or agent of the city or another position appointed by the city; (c) labour relations or other employee relations; (k) negotiations and related discussions respecting the proposed provision of an activity, work or facility that are at their preliminary stages and that, in the view of the Council, could reasonably be expected to harm the interests of the city if they were held in public. -

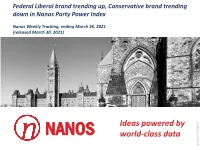

Views Dropped and 250 the Oldest Each Week Group of Rolling Where Week Average Data the Is Based Afour on 2021

Federal Liberal brand trending up, Conservative brand trending down in Nanos Party Power Index Nanos Weekly Tracking, ending March 26, 2021 (released March 30, 2021) Ideas powered by NANOS world-class data © NANOSRESEARCH Nanos tracks unprompted issues of concern every week and is uniquely positioned to monitor the trajectory of opinion on Covid-19. This first was on the Nanos radar the week of January 24, 2020. To access full weekly national and regional tracking visit the Nanos subscriber data portal. The Nanos Party Power Index is a composite score of the brand power of parties and is made up of support, leader evaluations, and accessible voter measures. Over the past four weeks the federal Liberal score has been trending up while the federal Conservative score has been trending down. Nik Nanos © NANOS RESEARCH © NANOS NANOS 2 ISSUE TRACKING - CORONAVIRUS 1,000 random interviews recruited from and RDD land- Question: What is your most important NATIONAL issue of concern? [UNPROMPTED] and cell-line sample of Source: Nanos weekly tracking ending March 26, 2021. Canadians age 18 years and 55 over, ending March 26, 2021. The data is based on a four 50 week rolling average where each week the oldest group of 45 250 interviews is dropped and 42.8 a new group of 250 is added. 40 A random survey of 1,000 Canadians is accurate 3.1 35 percentage points, plus or minus, 19 times out of 20. 30 25 Contact: Nik Nanos 20.5 [email protected] Ottawa: (613) 234-4666 x 237 20 Website: www.nanos.co 15.4 Methodology: 15 www.nanos.co/method 10 12.3 11.1 Subscribe to the Nanos data 6.9 portals to get access to 5 6.7 0.0 detailed breakdowns for $5 a month. -

Claimant's Memorial on Merits and Damages

Public Version INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR ICSID Case No. ARB/16/16 SETTLEMENT OF INVESTMENT DISPUTES BETWEEN GLOBAL TELECOM HOLDING S.A.E. Claimant and GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Respondent CLAIMANT’S MEMORIAL ON THE MERITS AND DAMAGES 29 September 2017 GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP Telephone House 2-4 Temple Avenue London EC4Y 0HB United Kingdom GIBSON, DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP 200 Park Avenue New York, NY 10166 United States of America Public Version TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 II. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 3 III. Canada’s Wireless Telecommunications Market And Framework For The 2008 AWS Auction................................................................................................................................. 17 A. Overview Of Canada’s Wireless Telecommunications Market Leading Up To The 2008 AWS Auction.............................................................................................. 17 1. Introduction to Wireless Telecommunications .................................................. 17 2. Canada’s Wireless Telecommunications Market At The Time Of The 2008 AWS Auction ............................................................................................ 20 B. The 2008 AWS Auction Framework And Its Key Conditions ................................... 23 1. The Terms Of The AWS Auction Consultation -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Actionalberta 87 HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE to TAKE IT

From: Action Alberta [email protected] Subject: ActionAlberta #87 - HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE TO TAKE IT? Date: December 11, 2019 at 8:06 PM To: Q.C. Alta.) [email protected] ACTION ALBERTA WEBSITE: Click here TWITTER: Click here FACEBOOK: Click here HELLO ALL (The Group of now 10,000+ and growing): HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE TO TAKE IT? HOW LONG DOES ALBERTA HAVE TO TAKE IT? (Robert J. Iverach, Q.C.) What Justin Trudeau and his Liberal government have intentionally done to the Western oil and gas industry is treason to all Canadians' prosperity. This is especially true when you consider that the East Coast fishing industry has been decimated, Ontario manufacturing is slumping and now the B.C. forest industry is in the tank. Justin Trudeau is killing our source of wealth. Alberta is in a "legislated recession" - a recession created by our federal government with its anti-business/anti-oil and gas legislation, such as Bill C-48 (the "West coast tanker ban") and Bill C-69 (the "pipeline ban"). This legislation has now caused at least $100 Billion of new and existing investment to flee Western Canada. Last month, Canada lost 72,000 jobs and 18,000 of those were in Alberta! Unemployment in Alberta has now risen to 7.2% with a notable increase in unemployment in the natural resources sector, while the unemployment rate for men under 25 years of age is now at almost 20%. How long must Albertans put up with the deliberate actions of a federal government that is intentionally killing our oil and gas business? When will Albertans say enough is enough? Well to this humble Albertan, the time is now! THE INEVITABLE TRUDEAU RECESSION WILL RAVAGE THE WEST AND THE MIDDLE CLASS (Diane Francis) The “hot mic” video of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau mocking President Donald Trump behind his back at the NATO conference is a major diplomatic blunder.