LGBT Families' Representation in Parenting Magazines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting a Queer Agenda for Hate Crime Scholarship

LGBT hate crime : promoting a queer agenda for hate crime scholarship PICKLES, James Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24331/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version PICKLES, James (2019). LGBT hate crime : promoting a queer agenda for hate crime scholarship. Journal of Hate Studies, 15 (1), 39-61. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk LGBT Hate Crime: Promoting a Queer Agenda for Hate Crime Scholarship James Pickles Sheffield Hallam University INTRODUCTION Hate crime laws in England and Wales have emerged as a response from many decades of the criminal justice system overlooking the structural and institutional oppression faced by minorities. The murder of Stephen Lawrence highlighted the historic neglect and myopia of racist hate crime by criminal justice agencies. It also exposed the institutionalised racism within the police in addition to the historic neglect of minority groups (Macpherson, 1999). The publication of the inquiry into the death of Ste- phen Lawrence prompted a move to protect minority populations, which included the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. Currently, Section 28 of the Crime and Disorder Act (1998) and Section 146 of the Criminal Justice Act (2003) provide courts the means to increase the sentences of perpetrators who have committed a crime aggravated by hostility towards race, religion, sexuality, disability, and transgender iden- tity. Hate crime is therefore not a new type of crime but a recognition of identity-aggravated crime and an enhancement of existing sentences. -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield Graduate School of Education & Allied GSEAP Faculty Publications Professions 7-2016 Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender Katherine M. Hertlein Erica E. Hartwell Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/education-facultypubs Copyright 2016 Taylor and Francis. A post-print has been archived with permission from the copyright holder. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journal of Bisexuality in 2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/ 15299716.2016.1200510 Peer Reviewed Repository Citation Hertlein, Katherine M. and Hartwell, Erica E., "Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender" (2016). GSEAP Faculty Publications. 126. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/education-facultypubs/126 Published Citation Hertlein, Katherine M., Erica E. Hartwell, and Mashara E. Munns. "Attitudes Toward Bisexuality According to Sexual Orientation and Gender." Journal of Bisexuality (July 2016) 16(3): 1-22. This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Elevated Physical Health Risk Among Gay Men Who Conceal Their Homosexual Identity

Health Psychology Copyright 1996 by the American Psychological As..q~ation, Inc. 1996, Vol. 15, No. 4, 243-251 0278-6133/96/$3.110 Elevated Physical Health Risk Among Gay Men Who Conceal Their Homosexual Identity Steve W. Cole, Margaret E. Kemeny, Shelley E. Taylor, and Barbara R. Visscher University of California, Los Angeles This study examined the incidence of infectious and neoplastic diseases among 222 HIV- seronegative gay men who participated in the Natural History of AIDS Psychosocial Study. Those who concealed the expression of their homosexual identity experienced a significantly higher incidence of cancer (odds ratio = 3.18) and several infectious diseases (pneumonia, bronchitis, sinusitis, and tuberculosis; odds ratio = 2.91) over a 5-year follow-up period. These effects could not be attributed to differences in age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, repressive coping style, health-relevant behavioral patterns (e.g., drug use, exercise), anxiety, depression, or reporting biases (e.g., negative affectivity, social desirability). Results are interpreted in the context of previous data linking concealed homosexual identity to other physical health outcomes (e.g., HIV progression and psychosomatic symptomatology) and theories linking psychological inhibition to physical illness. Key words: psychological inhibition, cancer, infectious diseases, homosexuality Since at least the second century AD, clinicians have noted Such results raise the possibility that any health risks associ- that inhibited psychosocial characteristics seem to be associ- ated with psychological inhibition may extend beyond the ated with a heightened risk of physical illness (Kagan, 1994). realm of emotional behavior to include the inhibition of Empirical research in this area has focused on inhibited nonemotional thoughts and other kinds of mental or social expression of emotions as a risk factor for the development of behaviors, experiences, and impulses. -

Identities That Fall Under the Nonbinary Umbrella Include, but Are Not Limited To

Identities that fall under the Nonbinary umbrella include, but are not limited to: Agender aka Genderless, Non-gender - Having no gender identity or no gender to express (Similar and sometimes used interchangeably with Gender Neutral) Androgyne aka Androgynous gender - Identifying or presenting between the binary options of man and woman or masculine and feminine (Similar and sometimes used interchangeably with Intergender) Bigender aka Bi-gender - Having two gender identities or expressions, either simultaneously, at different times or in different situations Fluid Gender aka Genderfluid, Pangender, Polygender - Moving between two or more different gender identities or expressions at different times or in different situations Gender Neutral aka Neutral Gender - Having a neutral gender identity or expression, or identifying with the preference for gender neutral language and pronouns Genderqueer aka Gender Queer - Non-normative gender identity or expression (often used as an umbrella term with similar scope to Nonbinary) Intergender aka Intergendered - Having a gender identity or expression that falls between the two binary options of man and woman or masculine and feminine Neutrois - Belonging to a non-gendered or neutral gendered class, usually but not always used to indicate the desire to hide or remove gender cues Nonbinary aka Non-binary - Identifying with the umbrella term covering all people with gender outside of the binary, without defining oneself more specifically Nonbinary Butch - Holding a nonbinary gender identity -

Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples

Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Gary J. Gates Summary Though estimates vary, as many as 2 million to 3.7 million U.S. children under age 18 may have a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender parent, and about 200,000 are being raised by same-sex couples. Much of the past decade’s legal and political debate over allowing same-sex couples to marry has centered on these couples’ suitability as parents, and social scientists have been asked to weigh in. After carefully reviewing the evidence presented by scholars on both sides of the issue, Gary Gates concludes that same-sex couples are as good at parenting as their different-sex counterparts. Any differences in the wellbeing of children raised in same-sex and different-sex families can be explained not by their parents’ gender composition but by the fact that children being by raised by same-sex couples have, on average, experienced more family instability, because most children being raised by same-sex couples were born to different-sex parents, one of whom is now in the same-sex relationship. That pattern is changing, however. Despite growing support for same-sex parenting, proportionally fewer same-sex couples report raising children today than in 2000. Why? Reduced social stigma means that more LGBT people are coming out earlier in life. They’re less likely than their LGBT counterparts from the past to have different-sex relationships and the children such relationships produce. At the same time, more same-sex couples are adopting children or using reproductive technologies like artificial insemination and surrogacy. -

University LGBT Centers and the Professional Roles Attached to Such Spaces Are Roughly

INTRODUCTION University LGBT Centers and the professional roles attached to such spaces are roughly 45-years old. Cultural and political evolution has been tremendous in that time and yet researchers have yielded a relatively small field of literature focusing on university LGBT centers. As a scholar-activist practitioner struggling daily to engage in a critically conscious life and professional role, I launched an interrogation of the foundational theorizing of university LGBT centers. In this article, I critically examine the discursive framing, theorization, and practice of LGBT campus centers as represented in the only three texts specifically written about center development and practice. These three texts are considered by center directors/coordinators, per my conversations with colleagues and search of the literature, to be the canon in terms of how centers have been conceptualized and implemented. The purpose of this work was three-fold. Through a queer feminist lens focused through interlocking systems of oppression and the use of critical discourse analysis (CDA) 1, I first examined the methodological frameworks through which the canonical literature on centers has been produced. The second purpose was to identify if and/or how identity and multicultural frameworks reaffirmed whiteness as a norm for LGBT center directors. Finally, I critically discussed and raised questions as to how to interrupt and resist heteronormativity and homonormativity in the theoretical framing of center purpose and practice. Hired to develop and direct the University of Washington’s first lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT2) campus center in 2004, I had the rare opportunity to set and implement with the collaboration of queerly minded students, faculty, and staff, a critically theorized and reflexive space. -

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights Research Team: Juliana Martínez, PhD; Ángela Duarte, MA; María Juliana Rojas, EdM and MA. Sentiido (Colombia) March 2021 The Elevate Children Funders Group is the leading global network of funders focused exclusively on the wellbeing and rights of children and youth. We focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence. Global Philanthropy Project (GPP) is a collaboration of funders and philanthropic advisors working to expand global philanthropic support to advance the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people in the Global1 South and East. TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ...................................................................................... 4 Acronyms .................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the Directors: ......................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................... 10 Report Outline ..........................................................................................13 MOBILIZING A GENDER-RESTRICTIVE WORLDVIEW .... 14 The Making of the Contemporary Gender-Restrictive Movement ................................................... 18 Instrumentalizing Cultural Anxieties ......................................... -

Education Policy: Issues Affecting Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth

Education Policy ISSUES AFFECTING LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER YOUTH by Jason Cianciotto and Sean Cahill National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute Washington, DC 1325 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20005-4171 Tel 202 393 5177 Fax 202 393 2241 New York, NY 121 West 27th Street, Suite 501 New York, NY 10001 Tel 212 604 9830 Fax 212 604 9831 Los Angeles, CA 5455 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 1505 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Tel 323 954 9597 Fax 323 954 9454 Cambridge, MA 1151 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel 617 492 6393 Fax 617 492 0175 Policy Institute 214 West 29th Street, 5th Floor New York, NY 10001 Tel 212 402 1136 Fax 212 228 6414 [email protected] www.ngltf.org © 2003 The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute When referencing this document, we recommend the following citation: Cianciotto, J., & Cahill, S. (2003). Education policy: Issues affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. New York: The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute is a think tank dedi- cated to research, policy analysis and strategy development to advance greater understanding and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. Contents PREFACE by Matt Foreman, Executive Director, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force . .vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . .1 1. LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER YOUTH: A CRITICAL POPULATION . .6 Introduction . .6 Gay Teen Forced to Read Aloud from Bible at School: A Profile of Thomas McLaughlin . .8 Methodological Barriers to Research on LGBT Youth . -

Interest Groups, Media, and the Elite Opinions’ Impact on Public Opinion

The American Gaze at the American Gays The American Gaze at the American Gays: Interest Groups, Media, and the Elite Opinions’ Impact on Public Opinion Honors Thesis 2013 Minkyung Kim UC Berkeley 2 Abstract In a recent wave of events, President Obama had announced his open acceptance and support of gay marriage in America; many celebrities have endorsed and said “It Gets Better”, to help with gay teenagers – and the majority of America stands behind them. But the trend towards an acceptance of gays has been established way before Obama, Lady Gaga, or “It Gets Better” Campaign. In this study, I seek the answer to the puzzling question of, “what made the public opinion change regarding the gay population?” After looking at public opinion trend, I seek the answer through some quantitative ways: through the political interest groups’ financial and media data; seeking media infiltration of “gay” in the news and TV shows; and lastly, the elite’s opinion through the channels of Supreme Court of the United States, State of the Union Address, and Presidential Campaign platforms of each parties. My data analysis goes back through roughly last thirty-five years (from 1977 to the present) of what “gay” is, and how it changed in the eyes of the American public. As none of the previous literature does a comprehensive look at all three factors as the change in attitude towards “the gays”, I discover that there is a general pattern, as there are more influences in the interest groups, the media, and the elites’ opinion, the public opinion in America went up, seemingly the former leading the latter; however, that pattern is not always so true – in fact, public opinion may lead elite opinion or media exposure. -

Media Reference Guide

media reference guide NINTH EDITION | AUGUST 2014 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 1 GLAAD MEDIA CONTACTS National & Local News Media Sports Media [email protected] [email protected] Entertainment Media Religious Media [email protected] [email protected] Spanish-Language Media GLAAD Spokesperson Inquiries [email protected] [email protected] Transgender Media [email protected] glaad.org/mrg 2 / GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION FAIR, ACCURATE & INCLUSIVE 4 GLOSSARY OF TERMS / LANGUAGE LESBIAN / GAY / BISEXUAL 5 TERMS TO AVOID 9 TRANSGENDER 12 AP & NEW YORK TIMES STYLE 21 IN FOCUS COVERING THE BISEXUAL COMMUNITY 25 COVERING THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY 27 MARRIAGE 32 LGBT PARENTING 36 RELIGION & FAITH 40 HATE CRIMES 42 COVERING CRIMES WHEN THE ACCUSED IS LGBT 45 HIV, AIDS & THE LGBT COMMUNITY 47 “EX-GAYS” & “CONVERSION THERAPY” 46 LGBT PEOPLE IN SPORTS 51 DIRECTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES 54 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 3 INTRODUCTION Fair, Accurate & Inclusive Fair, accurate and inclusive news media coverage has played an important role in expanding public awareness and understanding of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) lives. However, many reporters, editors and producers continue to face challenges covering these issues in a complex, often rhetorically charged, climate. Media coverage of LGBT people has become increasingly multi-dimensional, reflecting both the diversity of our community and the growing visibility of our families and our relationships. As a result, reporting that remains mired in simplistic, predictable “pro-gay”/”anti-gay” dualisms does a disservice to readers seeking information on the diversity of opinion and experience within our community. Misinformation and misconceptions about our lives can be corrected when journalists diligently research the facts and expose the myths (such as pernicious claims that gay people are more likely to sexually abuse children) that often are used against us. -

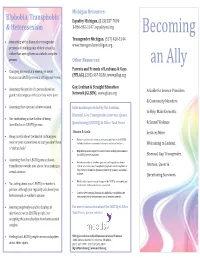

Becoming an Ally

Michigan Resources: Biphobia, Transphobia Equality Michigan, (313) 537-7000 & Heterosexism 1-866-962-1147, equalitymi.org Becoming Transgender Michigan, (517) 420-1544 • Interacting with a bisexual or transgender www.transgendermichigan.org person and thinking only of their sexuality, rather than seeing them as a whole, complex person. Other Resources: an Ally Parents and Friends of Lesbians & Gays • Changing your seat at a meeting or event because an LBGTIQ person is sitting next to you. (PFLAG), (202) 467-8180, www.pflag.org Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education • Assuming the gender of a person based on A Guide for Service Providers gender stereotypes or the sex they were born. Network (GLSEN), www.glsen.org & Community Members • Assuming that a person is heterosexual. Information provided by the Lesbian, to Help Make Domestic Bisexual, Gay, Transgender, Intersex, Queer, • Not confronting a joke for fear of being identified as an LBGTIQ person. Questioning (LBGTIQ) & Allies Task Force & Sexual Violence Mission & Goals: Services More • Being careful about the kind of clothing you • Enhance and increase access to advocacy and services for LBGTIQ wear or your mannerisms so that you don’t have individuals who are survivors of domestic and sexual violence. Welcoming to Lesbian, a “certain look.” • Help develop more supportive and inclusive working environments for LBGTIQ service providers. Bisexual, Gay, Transgender, • Assuming that if an LBGTIQ person shows • Provide education to member agencies and the public on issues friendliness towards you, she or he is making a related to heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia as Intersex, Queer & sexual advance. they relate to the unique dynamics of LBGTIQ domestic and sexual violence.