Social Workers' Attitudes Towards Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Adoptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples

Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Gary J. Gates Summary Though estimates vary, as many as 2 million to 3.7 million U.S. children under age 18 may have a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender parent, and about 200,000 are being raised by same-sex couples. Much of the past decade’s legal and political debate over allowing same-sex couples to marry has centered on these couples’ suitability as parents, and social scientists have been asked to weigh in. After carefully reviewing the evidence presented by scholars on both sides of the issue, Gary Gates concludes that same-sex couples are as good at parenting as their different-sex counterparts. Any differences in the wellbeing of children raised in same-sex and different-sex families can be explained not by their parents’ gender composition but by the fact that children being by raised by same-sex couples have, on average, experienced more family instability, because most children being raised by same-sex couples were born to different-sex parents, one of whom is now in the same-sex relationship. That pattern is changing, however. Despite growing support for same-sex parenting, proportionally fewer same-sex couples report raising children today than in 2000. Why? Reduced social stigma means that more LGBT people are coming out earlier in life. They’re less likely than their LGBT counterparts from the past to have different-sex relationships and the children such relationships produce. At the same time, more same-sex couples are adopting children or using reproductive technologies like artificial insemination and surrogacy. -

Education Policy: Issues Affecting Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth

Education Policy ISSUES AFFECTING LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER YOUTH by Jason Cianciotto and Sean Cahill National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute Washington, DC 1325 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20005-4171 Tel 202 393 5177 Fax 202 393 2241 New York, NY 121 West 27th Street, Suite 501 New York, NY 10001 Tel 212 604 9830 Fax 212 604 9831 Los Angeles, CA 5455 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 1505 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Tel 323 954 9597 Fax 323 954 9454 Cambridge, MA 1151 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel 617 492 6393 Fax 617 492 0175 Policy Institute 214 West 29th Street, 5th Floor New York, NY 10001 Tel 212 402 1136 Fax 212 228 6414 [email protected] www.ngltf.org © 2003 The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute When referencing this document, we recommend the following citation: Cianciotto, J., & Cahill, S. (2003). Education policy: Issues affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. New York: The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute is a think tank dedi- cated to research, policy analysis and strategy development to advance greater understanding and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. Contents PREFACE by Matt Foreman, Executive Director, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force . .vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . .1 1. LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER YOUTH: A CRITICAL POPULATION . .6 Introduction . .6 Gay Teen Forced to Read Aloud from Bible at School: A Profile of Thomas McLaughlin . .8 Methodological Barriers to Research on LGBT Youth . -

LGBT Parents and Their Children Prepared by Melanie L. Duncan M.A

LGBT Parents and their Children Prepared by Melanie L. Duncan M.A. & Kristin E. Joos, Ph.D. University of Florida Distributed by the Sociologists for Women in Society September 2011 Introduction Recently, international groups that advocate on the behalf of LGBT families have declared May 6, 2012 to be International Family Equality Day1. While this day is meant to highlight to increasingly visibility of LGBT families it is also a celebration of the diverse forms that families can take on. This is just one of the many changes that have occurred since the first version of this document was publishes, in 2003. Over the course of the past eight years, six states and Washington D.C. have come to legally recognize same-sex marriages, the Defense of Marriage Act is no longer being enforced, Don‟t Ask Don‟t Tell was repealed, and same-sex couples can now adopt in a number of states, including Florida2. Traditionally, depictions of the family have often centered on the heteronormative nuclear family of mother, father, and child(ren). However, as time has gone on we have seen that family forms have become increasingly diverse and include: single parents, child-free couples, parents who adopt or are foster parents, multiracial couples and their children, stepfamilies, etc. Parents who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), and their children are contributing to this societal shift that is broadening the traditional and idealized notion of family. The presence of LGBT families in media, courts, and research has grown over the last ten years. What may have been a previously labeled as the “gayby boom3” is now becoming a more commonly recognized by individuals and professionals means of forming a family. -

Bibliography on LGBT Parenting Issues (1983-2009) Brooks, D., & Goldberg, S. (2001). Gay and Lesbian Adoptive and Foster

. Bibliography on LGBT Parenting Issues (1983-2009) Brooks, D., & Goldberg, S. (2001). Gay and lesbian adoptive and foster care placements: Can they meet the needs of waiting children? Families in Society, 46(2), 147-157. Erich, S., Kanenberg, H., Case, H, Allen, T., & Bogdanos, T. (2009). An empirical analysis of factors affecting adolescent attachment in adoptive families with homosexual and straight parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 398-404. Erich, S., Leung, P., Kindle, P. & Carter, S. (2005). Gay and lesbian adoptive families: An exploratory study of family functioning, adoptive child’s behavior, and familial support networks. Journal of Family Social Work, 9, 17-32. Gates, G.J., Badgett, M.V.L., Macomber, J.E., & Chambers, K. (2007). Adoption and foster care by gay and lesbian parents in the United States. Technical report issues jointly by the Williams Institute (Los Angeles) and the Urban Institute (Washington, D.C.) Golombok, S., Spencer, A., & Rutter, M. (1983). Children in lesbian and single-parent households: Psychosexual and psychiatric appraisal. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(4), 551–572. Golombok, S., & Tasker, F. (1996). Do parents influence the sexual orientation of their children? Findings from a longitudinal study of lesbian families. Developmental Psychology, 32(1), 3–11. Golombok, S., Tasker, F., & Murray, C. (1997). Children raised in fatherless families from infancy: Family relationships and the socioemotional development of children of children of lesbian and single heterosexual mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 38, 783–791. Golombok, S., Perry, B., Burston, A., Murray, C., Mooney-Somers, J. & Stevens, M. (2003). Children with Lesbian Parents: A Community Study. -

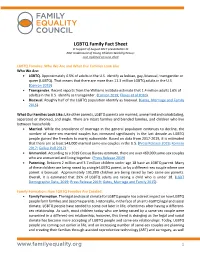

LGBTQ Family Fact Sheet in Support of August 2017 Presentation to NAC Undercount of Young Children Working Group: Last Updated on June 2020

LGBTQ Family Fact Sheet In Support of August 2017 presentation to NAC Undercount of Young Children Working Group: Last Updated on June 2020 LGBTQ Families: Who We Are and What Our Families Look Like Who We Are: • LGBTQ. Approximately 4.5% of adults in the U.S. identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ). That means that there are more than 11.3 million LGBTQ adults in the U.S. (Conron 2019). • Transgender. Recent reports from the Williams Institute estimate that 1.4 million adults (.6% of adults) in the U.S. identify as transgender. (Conron 2019; Flores et al 2016). • Bisexual. Roughly half of the LGBTQ population identify as bisexual. (Gates, Marriage and Family 2015). What Our Families Look Like: Like other parents, LGBTQ parents are married, unmarried and cohabitating, separated or divorced, and single. There are intact families and blended families, and children who live between households. • Married. While the prevalence of marriage in the general population continues to decline, the number of same-sex married couples has increased significantly in the last decade as LGBTQ people gained the freedom to marry nationwide. Based on data from 2017-2019, it is estimated that there are at least 543,000 married same-sex couples in the U.S. (Press Release 2019; Romero 2017; Gallup Poll 2017). • Unmarried. According to a 2019 Census Bureau estimate, there are over 469,000 same-sex couples who are unmarried and living together. (Press Release 2019). • Parenting. Between 2 million and 3.7 million children under age 18 have an LGBTQ parent. -

Same-Sex Parent Socialization: Understanding Gay and Lesbian Parenting Practices As Cultural Socialization

Journal of GLBT Family Studies ISSN: 1550-428X (Print) 1550-4298 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wgfs20 Same-Sex Parent Socialization: Understanding Gay and Lesbian Parenting Practices as Cultural Socialization Marykate Oakley, Rachel H. Farr & David G. Scherer To cite this article: Marykate Oakley, Rachel H. Farr & David G. Scherer (2017) Same-Sex Parent Socialization: Understanding Gay and Lesbian Parenting Practices as Cultural Socialization, Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13:1, 56-75, DOI: 10.1080/1550428X.2016.1158685 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2016.1158685 Published online: 06 Apr 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 195 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wgfs20 Download by: [University of Kentucky Libraries] Date: 01 February 2017, At: 12:13 JOURNAL OF GLBT FAMILY STUDIES 2017, VOL. 13, NO. 1, 56–75 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2016.1158685 Same-Sex Parent Socialization: Understanding Gay and Lesbian Parenting Practices as Cultural Socialization Marykate Oakleya, Rachel H. Farrb, and David G. Scherera aDepartment of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts; bDepartment of Psychology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Cultural socialization refers to the processes by which parents Gay and lesbian parents; communicate cultural values, beliefs, customs, and behaviors to cultural socialization; their children. To date, research on cultural socialization has children; parenting strategies focused primarily on racial- and ethnic-minority families, and more contemporary studies have examined these practices among international and transracial adoptive families. -

Attitudes Toward Same-Gender Adoption and Parenting: an Analysis of Surveys from 16 Countries

Attitudes Toward Same-Gender Adoption and Parenting: An Analysis of Surveys from 16 Countries Darrel Montero Abstract: Globally, little progress has been made toward the legalization of same-gender adoption. Of the nearly 200 United Nations members, only 15 countries with populations of 3 million or more have approved LGBT adoption without restrictions. The objectives of this paper are, first, to provide a brief background of the obstacles confronting same- gender adoption including the role of adoption agencies and parenting issues; second, to discuss the current legal status of the 15 countries which have approved same-gender adoption without restrictions; third, to report on recent public opinion regarding the legalization of same-gender adoption and parenting, drawing from previously published surveys conducted in 16 countries; and, fourth, to explore the implications for social work practice including social advocacy and social policy implementation. Keywords: Same-gender adoption, same-sex adoption, gay adoption, same-gender parenting To date, few papers have addressed the issue of same-gender adoption globally. As of 2013, only 15 major industrialized countries have approved same-gender adoption without restrictions. For the purpose of this paper, the term “without restrictions” refers to nations which allow joint adoption by same-gender couples, step-parent adoption (of their same-gender partner’s biological child), and adoption by a single gay or lesbian individual. Although Canada was the first country to approve same-gender -

SECURING LEGAL TIES for CHILDREN LIVING in LGBT FAMILIES a State Strategy and Policy Guide

SECURING LEGAL TIES FOR CHILDREN LIVING IN LGBT FAMILIES A State Strategy and Policy Guide July 2012 Authors In Partnership With A Companion Report to All Children Matter: How Legal and Social Inequalities Hurt LGBT Families. Both reports are co-authored by the Movement Advancement Project, the Family Equality Council, and the Center for American Progress. This report was authored by: This report was developed in partnership with: Movement Advancement Project Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute The Movement Advancement Project (MAP) is an independent The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, a national not- for-profit, is the leading research, policy and education 2 think tank that provides rigorous research, insight and analysis that help speed equality for LGBT people. MAP works organization in its field. The Institute’s mission is to provide collaboratively with LGBT organizations, advocates and leadership that improves laws, policies and practices— funders, providing information, analysis and resources that through sound research, education and advocacy—in order to help coordinate and strengthen their efforts for maximum better the lives of everyone touched by adoption. To achieve impact. MAP also conducts policy research to inform the its goals, the Institute conducts and synthesizes research, public and policymakers about the legal and policy needs of offers education to inform public opinion, promotes ethical LGBT people and their families. For more information, visit practices and legal reforms, and works to translate policy into www.lgbtmap.org. action. For more information, visit www.adoptioninstitute.org. Family Equality Council Equality Federation Family Equality Council works to ensure equality for LGBT Equality Federation is the national alliance of state- families by building community, changing public opinion, based lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) advocating for sound policy and advancing social justice for advocacy organizations. -

LGBT Families' Representation in Parenting Magazines

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Theses Department of Sociology Spring 5-10-2019 From Invisibility to Normativity: LGBT Families' Representation in Parenting Magazines Claire James Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses Recommended Citation James, Claire, "From Invisibility to Normativity: LGBT Families' Representation in Parenting Magazines." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses/84 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM INVISIBILITY TO NORMATIVITY: LGBT FAMILIES’ REPRESENTATION IN PARENTING MAGAZINES by CLAIRE JAMES Under the Direction of Katie Acosta, MA/PhD ABSTRACT This research compares the visibility of LGBT-parented families in the articles of two types of parenting magazines: Gay Parent Magazine, which targets LGBT families and Parents, which targets heterosexual two-parent families. I analyzed how the articles in each magazine portray LGBT-parent families, the articles’ rhetoric, and how such language reinforces or deviates from heteronormativity. I compare the differences between how families are represented in Parents magazine and Gay Parent Magazine in order to illustrate how homonormativity is reproduced. Using -

Working with Lesbian-Headed Families: What Social Workers Need to Know

Working with Lesbian-Headed Families: What Social Workers Need to Know Misty L. Wall Abstract: More gay men and lesbian women are choosing parenthood. One common challenge facing lesbian-headed families is how to navigate interactions with societies that are largely homophobic, heterocentric, or unaware of how to embrace non- traditional families. Systems may struggle to adjust services to meet the needs of modern family structures, including families led by lesbian women. The following are three areas of intervention (knowledge, creating affirmative space, and ways to incorporate inclusive language), informed by current literature, that allow social workers to create successful working relationships with members of lesbian-headed families. Keywords: Lesbian, same-sex couples, lesbian-headed families The landscape for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals (LGBT) has changed vastly within the last decade. For the first time in U.S. history, our president is openly supportive of same-sex marriage and all other formal extensions of equal rights to LGBT individuals. Despite considerable progress, the nuclear heterosexual family is still viewed by parts of western society as the “the norm” and the “preferred” family constellation for child rearing. Despite decades of research that have produced countless empirical studies showing lesbian women to be capable, protective, nurturing, loving parents (see the American Psychological Association for a list of studies), same-sex headed families are viewed by some Americans as deviant and potentially harmful to children (Short, Riggs, Perlesz, Brown, & Kane, 2007). Many lesbian women desire motherhood and are choosing to become parents in the context of same-sex relationships despite public and private challenges associated with that choice. -

Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples” by G

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY: LGBT INDIVIDUALS DR. VICTOR AND SAME-SEX COUPLES1 HARRIS Adapted from “Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples” by G. J. Gates, 2015, The Future of Children, 25(2), p. 89. Copyright 2015 by the Center for the Future of Children. 1. “Measures of social acceptance related to sexual relationships, parenting, and marriage recognition among same-sex couples all increased substantially in the last two decades” (Gates, [email protected] 2015, p. 68). 2. The constitutional right to marry was granted to same-sex couples by the U.S. Supreme Court in June of 2015 (Gates, 2015, p 69). 3. Between 1973 and 1991, the proportion of people who perceived same-sex sexual relationships as “wrong” showed 352-273-3523 little variance, “peaking at 77 percent in 1988 and 1991” (p. 68). 3028 D MCCARTY HALL D, 4. This number rapidly declined over the following two decades, GAINESVILLE, FL 32611 “from 66 percent in 1993 down to 40 percent in 2014” (p. 68). 5. “In 1988, only 12 percent of U.S. adults agreed that same-sex couples should have a right to marry” (p. 68). 6. By 2014, 57 percent of U.S. adults agreed to the same. COMPILED BY: PRAMI SENGUPTA Legal Recognition of Same-Sex Relationships 1. “Shifts in public attitudes toward same-sex relationships and families have been accompanied by similarly dramatic shifts in GRADUATE STUDENT granting legal status to same-sex couple relationships” (Gates, FAMILY, YOUTH AND 2015, p. 68). COMMUNITY SCIENCES 2. Same-sex couples were first recognized by California when the state implemented its domestic partnership registry in 1999. -

TRANSGENDER PARENTING: a REVIEW of EXISTING RESEARCH Rebecca L

TRANSGENDER PARENTING: A REVIEW OF EXISTING RESEARCH Rebecca L. Stotzer, Jody L. Herman, and Amira Hasenbush OCTOBER 2014 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report reviews existing research on the prevalence and characteristics of transgender people who are parents, the quality of relationships between transgender parents and their children, out- comes for children with a transgender parent, and the reported needs of transgender parents. Our analysis of the research to date, which includes 51 studies, has found the following: • Surveys show that substantial numbers of transgender respondents are parents, though at rates that appear lower than the U.S. general population. Of the 51 studies included in this review, most found that between one quarter and one half of transgender people report being parents. In the U.S. general population, 65% of adult males and 74% of adult females are parents (Halle, 2002). • Some studies suggest that that there may be substantial differences in the rates of parenting among trans men, trans women, and gender non-conforming individuals. In all the studies included in this review that provided data about different transgender subgroups, higher percentages of transgender women than transgender men reported having children. • Two studies have found that people who transition or “come out” as transgender later in life tend to have higher parenting rates than those people who identify as transgender and/or transition at younger ages. This higher rate of parenting could be due to individuals becoming biological parents before they identified as trans- gender or transitioned. • Of the six studies that asked about both “having children” and “living with children,” all found that there were more transgender respondents who reported having children than living with children.