LGBT Transracial Adoption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Family Building Directory of Family Building Services for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual And

DIRECTORY OF FAMILY BUILDING SERVICES FOR LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER PEOPLE LLLesbianLesbian and G Gayayayay F Familyamily B Buildinguilding PPProjectProject Ferre Institute, IncInc.... 2020201020 101010----2020202011111111 Lesbian and Gay Family Building Project The Lesbian and Gay Family Building Project is dedicated to helping lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in upstate New York achieve their goals of building and sustaining healthy families. The project offers educational programs, information and referral services, The Directory of Family Building Services, and support groups for LGBT parents and prospective parents. Our network of Pride and Joy Families provides social and educational activities and a sense of community to LGBTQ parents and their children. The Lesbian and Gay Family Building Project was started in 2000 with a grant from New York State to Ferre Institute, Inc. Ferre is a 501(C)(3) organization that provides infertility education, family building resources and genetic counseling. Staff Members Claudia E. Stallman, Project Director Karen J. Armstrong, Health Educator Luba Djurdjinovic, Executive Director, Ferre Institute, Inc. Murray L. Nusbaum, MD, Medical Director, Ferre Institute, Inc. Cover Art by Ada Stallman © 2010 by Lesbian and Gay Family Building Project Ferre Institute, Inc. 124 Front Street, Binghamton, NY 13905 (607) 724-4308 (607) 724-8290 FAX [email protected] www.PrideAndJoyFamilies.org www.LGBTServicesDIrectory.com www.LGBTHealthInitiative.org 2 Lesbian and GaGayy Family Building Project Ferre Institute, Inc., 124 Front Street, Binghamton, NY 13905 Phone: 607.724.4308 Fax: 607.724.8290 Email: [email protected] Website: www.PrideAndJoyFamilies.org Dear Reader: The Lesbian and Gay Family Building Project, a program of the Ferre Institute, Inc., is pleased to provide the 2010-2011 edition of its Directory of Family Building Services for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People . -

Gay Marriage Party Ends For

'At Last* On her way to Houston, pop diva Cyndi Lauper has a lot to say. Page 15 voicewww.houstonvoice.com APRIL 23, 2004 THIRTY YEARS OF NEWS FOR YOUR LIFE. AND YOUR STYLE. Gay political kingmaker set to leave Houston Martin's success as a consultant evident in city and state politics By CHRISTOPHER CURTIS Curtis Kiefer and partner Walter Frankel speak with reporters after a Houston’s gay and lesbian com circuit court judge heard arguments last week in a lawsuit filed by gay munity loses a powerful friend and couples and the ACLU charging that banning same-sex marriages is a ally on May 3, when Grant Martin, violation of the Oregon state Constitution. (Photo by Rick Bowmer/AP) who has managed the campaigns of Controller Annise Parker, Council member Ada Edwards, Texas Rep. Garnet Coleman and Sue Lovell, is moving to San Francisco. Back in 1996 it seemed the other Gay marriage way around: Martin had moved to Houston from San Francisco after ending a five-year relationship. Sue Lovell, the former President party ends of the Houston Gay and Lesbian Political Caucus (PAC), remembers first hearing of Martin through her friend, Roberta Achtenberg, the for mer Clinton secretary of Fair for now Housing and Equal Opportunity. “She called me and told me I have a dear friend who is moving back to Ore. judge shuts down weddings, Houston and I want you to take Political consultant Grant Martin, the man behind the campaigns of Controller Annise Parker, good care of him.” but orders licenses recognized Council member Ada Edwards, Texas Rep. -

Perspectives on Equity in LGBTQ Adoption

Perspectives on Equity in LGBTQ Adoption By Rachel Albert, on behalf of Jewish Family & Children’s Service and Adoption Resources, with funding from the Krupp Family Foundation adoptionresources.org Waltham Headquarters | Brighton | Canton | North Shore | Central MA For more information visit jfcsboston.org or call 781-647-JFCS (5327). Context Approximately 65,000 adopted children nationwide are In March of 2017, Jewish Family & Children’s Service, with being raised by same-sex parents and approximately two generous support from the Krupp Family Foundation, com- million gay and lesbian people living in the U.S. have con- missioned a study on the challenges that LGBTQ people face sidered adoptioni. Although the U.S. Supreme Court grant- before, during, and after the adoption process. This report ed full parental rights to same-sex married couples in 2015ii, summarizes these find- many LGBTQ prospective parents still encounter explicit or ings, which are based on 34 covert discrimination, particularly from faith-based adop- in-person, telephone, and “The adoption process is one tion agenciesiii. As is often true of minority groups, it appears email interviews, support- thing, but you’re an adoptive that LGBTQ people also experience amplified versions of ed by an extensive review family for your entire lives. the same difficulties faced by heterosexual couples seeking of the academic literature There are all sorts of ongoing to adopt. on adoption. issues, especially if you’ve adopted transracially.” —Lesbian adoptive mother Executive Summary: Key Findings 1 During the adoption process, prospective LGBTQ parents adoptive couples were also challenged by parenting medically face amplified versions of the same difficulties experienced by complex babies due to the dramatic increase in prenatal sub- their heterosexual counterparts: confusion, financial hard- stance exposure. -

The Public Eye, Summer 2010

Right-Wing Co-Opts Civil Rights Movement History, p. 3 TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL R PublicEyeESEARCH ASSOCIATES Summer 2010 • Volume XXV, No.2 Basta Dobbs! Last year, a coalition of Latino/a groups suc - cessfully fought to remove anti-immigrant pundit Lou Dobbs from CNN. Political Research Associates Executive DirectorTarso Luís Ramos spoke to Presente.org co-founder Roberto Lovato to find out how they did it. Tarso Luís Ramos: Tell me about your organization, Presente.org. Roberto Lovato: Presente.org, founded in MaY 2009, is the preeminent online Latino adVocacY organiZation. It’s kind of like a MoVeOn.org for Latinos: its goal is to build Latino poWer through online and offline organiZing. Presente started With a campaign to persuade GoVernor EdWard Rendell of PennsYlVania to take a stand against the Verdict in the case of Luis RamíreZ, an undocumented immigrant t t e Who Was killed in Shenandoah, PennsYl - k n u l Vania, and Whose assailants Were acquitted P k c a J bY an all-White jurY. We also ran a campaign / o t o to support the nomination of Sonia h P P SotomaYor to the Supreme Court—We A Students rally at a State Board of Education meeting, Austin, Texas, March 10, 2010 produced an “I Stand With SotomaYor” logo and poster that people could displaY at Work or in their neighborhoods and post on their Facebook pages—and a feW addi - From Schoolhouse to Statehouse tional, smaller campaigns, but reallY the Curriculum from a Christian Nationalist Worldview Basta Dobbs! continues on page 12 By Rachel Tabachnick TheTexas Curriculum IN THIS ISSUE Controversy objectiVe is present—a Christian land goV - 1 Editorial . -

Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples

Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples Gary J. Gates Summary Though estimates vary, as many as 2 million to 3.7 million U.S. children under age 18 may have a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender parent, and about 200,000 are being raised by same-sex couples. Much of the past decade’s legal and political debate over allowing same-sex couples to marry has centered on these couples’ suitability as parents, and social scientists have been asked to weigh in. After carefully reviewing the evidence presented by scholars on both sides of the issue, Gary Gates concludes that same-sex couples are as good at parenting as their different-sex counterparts. Any differences in the wellbeing of children raised in same-sex and different-sex families can be explained not by their parents’ gender composition but by the fact that children being by raised by same-sex couples have, on average, experienced more family instability, because most children being raised by same-sex couples were born to different-sex parents, one of whom is now in the same-sex relationship. That pattern is changing, however. Despite growing support for same-sex parenting, proportionally fewer same-sex couples report raising children today than in 2000. Why? Reduced social stigma means that more LGBT people are coming out earlier in life. They’re less likely than their LGBT counterparts from the past to have different-sex relationships and the children such relationships produce. At the same time, more same-sex couples are adopting children or using reproductive technologies like artificial insemination and surrogacy. -

We Let Bill Cosby Into Our Homes, So He Owes Us an Explanation

9/30/2015 We Let Bill Cosby Into Our Homes, So He Owes Us an Explanation We Let Bill Cosby Into Our Homes, So He Owes Us an Explanation KEVIN COKLEY NOVEMBER 20, 2014 America's once-favorite TV dad needs to take his own advice. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke) Entertainer and former classmate Bill Cosby speaks during a public memorial service for Philadelphia Inquirer co-owner Lewis Katz Wednesday, June 4, 2014, at Temple University in Philadelphia. hile the natural inclination is to separate Bill Cosby’s television character W from his real life persona, the show we remember so fondly was not called The Huxtable Show. It was The Cosby Show. We did not really welcome Heathcliff into our homes. We welcomed Bill. http://prospect.org/article/weletbillcosbyourhomessoheowesusexplanation 1/4 9/30/2015 We Let Bill Cosby Into Our Homes, So He Owes Us an Explanation It is Cosby, the accused serial rapist of 15 women from whom we await an explanation. He has the time: His planned NBC project was just pulled in the face of these resurfaced allegations. He won’t be cashing any residual checks from shows streamed on Netflix because like any contagion, everything Cosby is associated with is now contaminated. This reckoning particularly stings because of Cosby’s decades-long campaign of respectability politics within the black community. This reckoning particularly stings because of Cosby’s decades-long campaign of respectability politics within the black community. For years he has offered a socially conservative critique of certain elements of black culture, where he has emphasized individual responsibility and a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps mentality. -

PRESS KIT Baby Daddy OVERVIEW

PRESS KIT Baby Daddy OVERVIEW FILM TITLE ALEC MAPA: BABY DADDY SYNOPSIS Actor and comedian Alec Mapa (America's Gaysian Sweetheart) shares hilarious and heartfelt stories about how his life has changed since he and his husband adopted a five year old through the foster care system. No topic is off limits in this raunchy yet moving film of his award-winning one-man show: Alec's sex life, hosting gay porn award shows, midlife crisis, musical theatre, reality television, bodily functions, stage moms vs. baseball dads, and the joys, challenges, and unexpected surprises of fatherhood. Includes behind-the-scenes footage of his family's home life on a busy show day. " / / Thought Moment Media Mail: 5419 Hollywood Blvd Suite C-142 Los Angeles, CA 90027 Phone: 323-380-8662 Jamison Hebert | Executive Producer [email protected] Andrea James | Director [email protected] / Ê " TRT: 78 minutes Exhibition Format: DVD, HDCAM Aspect Ratio: 16:9 or 1.85 Shooting Format: HD Color, English ," -/ÊEÊ -/, 1/" Ê +1, - For all inquiries, please contact Aggie Gold 516-223-0034 [email protected] -/6Ê- , Ê +1, - For all inquiries, please contact Jamison Hebert 323-380-8662 [email protected] /"1/Ê" /Ê ÊÊUÊÊ/"1/" /° "ÊÊUÊÊÎÓÎÎnänÈÈÓÊÊ Baby Daddy KEY CREDITS Written and Performed by ALEC MAPA Directed by ANDREA JAMES Executive Producers JAMISON HEBERT ALEC MAPA ANDREA JAMES Director of Photography IAN MCGLOCKLIN Original Music Composed By MARC JACKSON Editors ANDREA JAMES BRYAN LUKASIK Assistant Director PATTY CORNELL Producers MARC CHERRY IAN MCGLOCKLIN Associate Producers BRIELLE DIAMOND YULAUNCZ J. DRAPER R. MICHAEL FIERRO CHRISTIAN KOEHLER-JOHANSEN JIMMY NGUYEN MARK ROSS-MICHAELS MICHAEL SCHWARTZ & MARY BETH EVANS RICHARD SILVER KAREN TAUSSIG Sound Mixer and Sound Editor SABI TULOK Stage Manager ERIKA H. -

Education Policy: Issues Affecting Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth

Education Policy ISSUES AFFECTING LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER YOUTH by Jason Cianciotto and Sean Cahill National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute Washington, DC 1325 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20005-4171 Tel 202 393 5177 Fax 202 393 2241 New York, NY 121 West 27th Street, Suite 501 New York, NY 10001 Tel 212 604 9830 Fax 212 604 9831 Los Angeles, CA 5455 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 1505 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Tel 323 954 9597 Fax 323 954 9454 Cambridge, MA 1151 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel 617 492 6393 Fax 617 492 0175 Policy Institute 214 West 29th Street, 5th Floor New York, NY 10001 Tel 212 402 1136 Fax 212 228 6414 [email protected] www.ngltf.org © 2003 The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute When referencing this document, we recommend the following citation: Cianciotto, J., & Cahill, S. (2003). Education policy: Issues affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. New York: The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute is a think tank dedi- cated to research, policy analysis and strategy development to advance greater understanding and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. Contents PREFACE by Matt Foreman, Executive Director, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force . .vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . .1 1. LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER YOUTH: A CRITICAL POPULATION . .6 Introduction . .6 Gay Teen Forced to Read Aloud from Bible at School: A Profile of Thomas McLaughlin . .8 Methodological Barriers to Research on LGBT Youth . -

(Pdf) Download

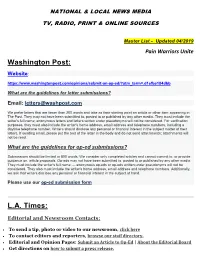

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Transracial Parenting in Foster Care and Adoption

Transracial Parenting in Foster Care & Adoption - Strengthening Your Bicultural Family This guidebook was created to help parents and children in transracial homes learn how to thrive in and celebrate their bicultural family; and for children to gain a strong sense of racial identity and cultural connections. 1 Transracial Parenting in Foster Care & Adoption - Strengthening Your Bicultural Family 2 Transracial Parenting in Foster Care & Adoption - Strengthening Your Bicultural Family Table of Contents: Page # INTRODUCTION 4 A TRANSRACIALLY-ADOPTED CHILD’S BILL OF RIGHTS 5 TRANSRACIAL PARENTING PLEDGE 6 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A TRANSRACIAL FAMILY? 7 HOW FAR HAVE WE COME? THE HISTORY OF TRANSRACIAL FAMILIES 8 - 10 GENERAL PARENTING TASKS FOR TRANSRACIAL PARENTS 11 - 14 HOW TO CONNECT YOUR CHILD TO THEIR CULTURE - 15 - 16 AND HOW TO BECOME A BICULTURAL FAMILY THE VOICES OF ADULT TRANSRACIAL ADOPTEES 17 - 24 RACISM AND DISCRIMINATION – FOSTERING RACIAL COPING SKILLS 25 - 28 ANSWERING TOUGH QUESTIONS 28 - 29 SKIN CARE & HAIR CARE 30 - 32 RESOURCES 33 - 46 General Transracial Resources Online Help, Books, Videos, Toys & Dolls Organizations & Internet Resources Cultural Camps African American Resources Asian American Resources Native American Resources Hispanic Resources European American Resources Arab American Resources Language & Self-assessment tools 3 Transracial Parenting in Foster Care & Adoption - Strengthening Your Bicultural Family INTRODUCTION According to transracial adoption expert Joseph Crumbley, all foster children, whether in a transracial placement or not, worry “Will I be accepted in this home, even if I am from a different (biological) family?” Children in transracial homes also worry “Will I be accepted even if I’m from a different race?” This booklet will help you understand the importance of race and culture for your family; and share helpful hints, parenting tips and resources for you on the culturally rich journey of transracial parenting. -

Olivia Rodrigo's

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 1, 2021 Page 1 of 27 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Olivia Rodrigo’s ‘Drivers License’ Tops Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience impressions, up 16%). Top Country• Morgan Albums Wallen’s chart dated AprilHot 18. In its first 100 week (ending for April 9),7th it Week, Chris Brown & earned‘Dangerous’ 46,000 equivalentBecomes album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingOnly to Country Nielsen Album Music/MRC Data.Young Thug’s ‘Goand total Crazy’ Country Airplay No. Jumps1 as “Catch” (Big Machine to Label No. Group) ascends 3 Southsideto Spend marksFirst Seven Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartWeeks and fourth at No. top 1 10.on It follows freshman LP BY GARY TRUST Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloBillboard, which 200 arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You Olivia Rodrigo’s “Drivers License” logs a seventh ing Feb. -

International LGBT Family Organizations Announce

International LGBT Family Organizations Announce "International Family Equality Day” for 2012 Lesbian and gay family equality activists from around the world, hosted by R Family Vacations, met in Florida for a week of discussions in the first ever International Symposium of LGBT Family Organizations. The group of American, European and Canadian organizations decided on several cooperation initiatives, and the establishment of an "InternationalFamily Equality Day"to take place on May 6, 2012. New York, NY (PRWEB) July 29, 2011 -- The movement for equal treatment of LGBT-headed families took another significant step forward with the first ever International Symposium of LGBT Family Organizations which took place in Florida on July 9-16, 2011. The symposium was part of an effort to increase international cooperation among LGBT family organizations worldwide, led by Family Equality Council, America’s foremost advocate for LGBT families, the Network of European LGBT Families Associations (NELFA) and the Canadian LGBT Parenting Network based in Toronto. The symposium was hosted by the gay and lesbian family travel company R Family Vacations, as part of their week-long international vacation at Club Med Sandpiper resort in Florida. NELFA representatives from several European countries, along with Canadian representatives, joined Americans from Family Equality Council in hosting several workshops and a public panel about "LGBT Families Around the World." Facilitated by Jennifer Chrisler, executive director of Family Equality Council, the panel examined successes and challenges in the social and political realm across different cultures. Parents from around the world shared what it is like to be an LGBT family in their respective countries, including their experience at schools, places of worship, and when accessing government and medical services.