Bookviewcafe-Samplechapters.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OR KILL ME.Pdf

OR KILL ME!! Heresies, Rants, Sermons, Epistles, and Other Foul Words of The Good Reverend Roger 1 or kill me 2 CONTENTS PART ONE: Sermons 3 PART TWO: Heresies 85 PART THREE:Millions of Screaming Yahoos 98 PART FOUR: Epistles 168 PART FIVE: Life in the Age of the Dumb 182 PART SIX: Rants 203 PART SEVEN: Miscellaneous 233 or kill me 3 PART ONE: ROGER’S SERMONS or kill me 4 Rev Roger Sermon #1: A rant/sermon from the Good Reverend Roger Originally posted January 23, 2003 Brothers, Sisters, and Others, I speak to you (or rather write to you) tonight about the dangers of backsliding...For are there not those who go about quoting the Principia and St Wilson the Obscure; and do so having forgotten the message behind those glib words? To be a discordian is far more than rote memorization of an author's words... It is, in essence, one of the few remaining ways in which a person might be free. To lapse into dogma and the random spouting of anothers word is to deny that freedom! Can I get an "Amen"? In this new decade, our rights are stripped from us inch by inch, and day by day. We can now be detained (no more fun for YOU, Bubba...Ever) without counsel, our mail and our email can be read sans warrant, and even the so-called "opposition" has caved into this fascism, Eris damn their black souls. They would have ORDER. Law. Regulation. In short, they would have all that we disdain; truly, they would make the WORLD itself grey, had they the power (and they might yet). -

Swimming As Punching Their Way Through Water

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Feiwel and Friends ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e- book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Diarmuid the end You’d think it would feel weird being nearly naked in front of so many people, but it doesn’t. I ping my swimsuit straps for luck, once right, twice left, walk out poolside, and take a deep breath, inhaling the familiar tang of chlorine and feet. It sounds gross, but that smell is so exciting. I’m where I belong. I’m one of the fastest swimmers in my county. That’s why I’m here—trying out for a High Performance Training Camp that will set me on my way to Team Great Britain. I’ve wanted this for as long as I can remember. So … you know, no pressure, not a big deal, whev. I think I’m sweating inside my ears. I pad along the side of the pool, watching the heat before mine. Older swimmers power up and down; they look so strong—they’re not so much swimming as punching their way through water. -

The Apocalyptic Book List

The Apocalyptic Book List Presented by: The Post Apocalyptic Forge Compiled by: Paul Williams ([email protected]) As with other lists compiled by me, this list contains material that is not strictly apocalyptic or post apocalyptic, but that may contain elements that have that fresh roasted apocalyptic feel. Because I have not read every single title here and have relied on other peoples input, you may on occasion find a title that is not appropriate for the intended genre....please do let me know and I will remove it, just as if you find a title that needs to be added...that is appreciated as well. At the end of the main book list you will find lists for select series of books. Title Author 8.4 Peter Hernon 905 Tom Pane 2011, The Evacuation of Planet Earth G. Cope Schellhorn 2084: The Year of the Liberal David L. Hale 3000 Ad : A New Beginning Jon Fleetwood '48 James Herbert Abyss, The Jere Cunningham Acts of God James BeauSeigneur Adulthood Rites Octavia Butler Adulthood Rites, Vol. 2 Octavia E. Butler Aestival Tide Elizabeth Hand Afrikorps Bill Dolan After Doomsday Poul Anderson After the Blue Russel C. Like After the Bomb Gloria D. Miklowitz After the Dark Max Allan Collins After the Flames Elizabeth Mitchell After the Flood P. C. Jersild After the Plague Jean Ure After the Rain John Bowen After the Zap Michael Armstrong After Things Fell Apart Ron Goulart After Worlds Collide Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie Aftermath Charles Sheffield Aftermath K. A. Applegate Aftermath John Russell Fearn Aftermath LeVar Burton Aftermath, The Samuel Florman Aftershock Charles Scarborough Afterwar Janet Morris Against a Dark Background Iain M. -

The Truth About Elvis” Movie Website from Back in March 2007 – This Is Reproduced Here for Educational Purposes Only

THIS IS TEXT FROM THE RESEARCH SECTION OF “THE TRUTH ABOUT ELVIS” MOVIE WEBSITE FROM BACK IN MARCH 2007 – THIS IS REPRODUCED HERE FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY. PLEASE CHECK OUT THE GROUP ON FACEBOOK FOR MORE INFORMATION OR TO HELP WITH THE SEARCH FOR THE TRUTH. https://www.facebook.com/groups/48484318100/ OR MICKEY'S WEBSITE AT http://elvisconspiracy.webs.com/ Cheers & TCB! I'm going to post sightings, leads and research here. I'll post this information as I go along, so you can see some of the information I'm using to move forward. FROM ME: WE REALLY APPRECIATE THE EMAILS WE RECEIVE FROM FANS. LET US KNOW IF YOU HAVE ANY INTERESTING NEWS. THANKS, ADAM 3/14/07 Hi Adam, I finally had the chance to read "Elvis & Me by Priscilla and thought I'd share a little info with you. As I read the book, I really find it hard to believe that Priscilla would put some of the information she has in the book if Elvis was alive. There is quite a bit of their intimacy moments in the book and knowing what I've read about the two of them, it's hard to believe Priscilla even sharing this information. All I know is that I have very mixed feelings about the whole Elvis thing. Is it a money gimmick and/or just to keep Elvis and themselves in the limelight light. I do know that people are out to make a buck off of him. Some of those addresses on People Search are phony and they shouldn't be allowed to rip people off by using his middle initial and date of birth. -

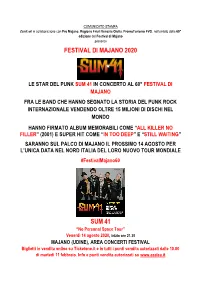

Festival Di Majano 2020 Sum 41

COMUNICATO STAMPA Zenit srl in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismo FVG, nell’ambito della 60° edizione del Festival di Majano presenta FESTIVAL DI MAJANO 2020 LE STAR DEL PUNK SUM 41 IN CONCERTO AL 60° FESTIVAL DI MAJANO FRA LE BAND CHE HANNO SEGNATO LA STORIA DEL PUNK ROCK INTERNAZIONALE VENDENDO OLTRE 15 MILIONI DI DISCHI NEL MONDO HANNO FIRMATO ALBUM MEMORABILI COME “ALL KILLER NO FILLER” (2001) E SUPER HIT COME “IN TOO DEEP” E “STILL WAITING” SARANNO SUL PALCO DI MAJANO IL PROSSIMO 14 AGOSTO PER L’UNICA DATA NEL NORD ITALIA DEL LORO NUOVO TOUR MONDIALE #FestivalMajano60 SUM 41 “No Personal Space Tour” Venerdì 14 agosto 2020, inizio ore 21.30 MAJANO (UDINE), AREA CONCERTI FESTIVAL Biglietti in vendita online su Ticketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita autorizzati dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. Info e punti vendita autorizzati su www.azalea.it Secondo annuncio internazionale per il Festival di Majano, storica rassegna musicale, culturale e enogastronomica del Friuli Venezia Giulia che festeggia nel 2020 i suoi 60° anni attestandosi come una delle manifestazioni più longeve e di successo dell’estate. Dopo il concerto con protagonisti i Bad Religion, i cui biglietti sono andati in vendita nelle scorse settimane, ecco ufficializzato oggi l’arrivo delle star del punk rock mondiale Sum 41, che saranno straordinariamente in concerto sul palco dell’Aera Concerti il prossimo venerdì 14 agosto 2020. I biglietti per questo nuovo grande appuntamento musicale dell’estate, organizzato da Zenit srl, in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismoFVG e Hub Music Factory, saranno in vendita online su Tiketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita del circuito dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Preliminary Program Schedule for Conjosé

ConJose - the 60th World Science Fiction Convention 08/26/02 11:13 PM Worldcon Aug. 29 to Sept. 2, 2002 San José Main - Participants - KaffeKlatsches - Autographs - Filk -Writers Workshop - FAQ Preliminary Program Schedule for ConJosé The preliminary version of the ConJosé program is now available. While we do not expect major changes, it is inevitable that there will be some updates between now and the convention. Please check this page for updates, and also look for the program change sheets that will be distributed at the convention. Updated: 25 August 2002 Thursday - Friday - Saturday - Sunday - Monday Early Morning Writing Exercises Monday 8:30am CC G Film: Hugo Winner Best Dramatic Presentation Monday 9:30am F Imperial Ball Soviet Space Disasters Monday 10:00am CC A1A8 Some have been published, many have been hidden, even from people in Russia. Hear about the ones you may not have known about before. Hugh S. Gregory Acceptance of High Technology: The Telephone Monday 10:00am CC A2A7 Technoshock! The adoption of new technology has always been fraught with stories of skepticism and sometimes terror. This is true not only of the technologies we are trying to conquer today, but also of technologies of the past; such as the telephone, the automobile and the airplane. What rumors and wild stories were circulated about past technologies http://www.conjose.org/Program/scheduleMon.html Page 1 of 15 ConJose - the 60th World Science Fiction Convention 08/26/02 11:13 PM and how do they compare to the stories about today's technology? Vernor Vinge, Chris Garcia, Kevin P. -

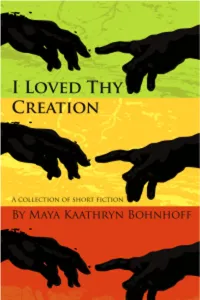

I Loved Thy Creation

I Loved Thy Creation A collection of short fiction by Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff O SON OF MAN! I loved thy creation, hence I created thee. Bahá’u’lláh Copyright 2008, Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff and Juxta Publishing Limited. www.juxta.com. Cover image "© Horvath Zoltan | Dreamstime.com" ISBN 978-988-97451-8-9 This book has been produced with the consent of the original authors or rights holders. Authors or rights holders retain full rights to their works. Requests to reproduce the contents of this work can be directed to the individual authors or rights holders directly or to Juxta Publishing Limited. Reproduction of this book in its current form is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license outlined below. This book is released as part of Juxta Publishing's Books for the World program which aims to provide the widest possible access to quality Bahá'í-inspired literature to readers around the world. Use of this book is governed by the Juxta Publishing Books for the World license: 1. This book is available in printed and electronic forms. 2. This book may be freely redistributed in electronic form so long as the following conditions are met: a. The contents of the file are not altered b. This copyright notice remains intact c. No charges are made or monies collected for redistribution 3 The electronic version may be printed or the printed version may be photocopied, and the resulting copies used in non-bound format for non-commercial use for the following purposes: a. Personal use b. Academic or educational use When reproduced in this way in printed form for academic or educational use, charges may be made to recover actual reproduction and distribution costs but no additional monies may be collected. -

Loscon 34 Program Book

LosconLoscon 3434 WelcomeWelcome to the LogbookLogbook of the “DIG”“DIG” LAX Marriott November 23 - 25, 2007 Robert J. Sawyer Author Guest Theresa Mather Artist Guest Capt. David West Reynolds Fan Guest Dr. James Robinson Music Guest 1 2 Table of Contents Anime .................................. Pg 68 Kids’ Night Out ..................... Pg 63 Art Show .............................. Pg 66 Listening Lounge .................. Pg 71 Awards Masquerade .......................... Pg 59 Evans-Freehafer ................ Pg 56 Members List ................. Pg 75-79 Forry ................................. Pg 57 Office / Lost & Found .......... Pg 71 Rotsler .............................. Pg 58 Photography/Videotape Policies .... Pg 70 Autographs .......................... Pg 73 Programming Panels ....... Pg 38-47 Bios Regency Dancing .................. Pg 62 Author Guest of Honor .........Pg 8-11 Registration .......................... Pg 71 Artist Guest of Honor ........ Pg 12-13 Room Parties ........................ Pg 63 Music Guest of Honor ........ Pg 16-17 Security Fan Guest of Honor ................. Pg 14 Rules & Regulations ..... Pg 70,73 Program Guests ........... Pg 30-37 No Smoking Policy ............. Pg 73 Blood Drive ........................... Pg 53 Weapons Policy ........... Pg 70,73 Chair’s Message .................. Pg 4-5 Special Needs ....................... Pg 60 Children’s Programming ........ Pg 68 Special Stories Committee & Staff ............. Pg 6-7 Peking Man .................. Pg 18-22 Computer Lounge ............... -

Winter 2020 Pegasus Books

PEGASUS BOOKS WINTER 2020 PEGASUS BOOKS WINTER 2020 NEW HARDCOVERS JANUARY MARKETING $27.95 | Hardcover • Social media Territory: U.S. (X) • Co-op available ISBN: 978-1-64313-367-6 • Major review attention 6 x 9 | 304 pages | CQ 16 • 2020 is the 400th anniversary 8 pages of B&W illustrations of the sailing of the Mayflower History 2 | PEGASUS BOOKS | WINTER 2020 | NEW HARDCOVERS THE JOURNEY TO THE MAYFLOWER God’s Outlaws and the Invention of Freedom Stephen Tomkins An authoritative and immersive history of the far-reaching—and often dangerous—events in England that led to the sailing of the Mayflower. 2020 brings readers the 400th anniversary of the sailing of the Mayflower—the ship that took the Pilgrim Fathers to the New World. It is a foundational event in American history, but it began as an English story, which pioneered the idea of religious freedom. The illegal underground movement of Protestant separatists from Elizabeth I’s Church of England is a story of subterfuge and danger, arrests and interrogations, prison and executions. It starts with Queen Mary’s attempts to burn Protestantism out of England, which created a Protestant underground. Later, when Elizabeth’s Protestant reforma- tion didn’t go far enough, radicals recreated that underground, meeting illegally throughout England, facing prison and death for their crimes. They went into exile in the Netherlands, where they lived in poverty—and finally to the New World. Historian Stephen Tomkins tells this fascinating story—one that is rarely told as an important piece of English, as well as American, history—that is full of contemporary relevance: religious violence, the threat to national security, freedom of religion, and tolerance of dangerous opinions. -

Here Without You 3 Doors Down

Links 22 Jacks - On My Way 3 Doors Down - Here without You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - When I m Gone 30 Seconds to Mars - City of Angels - Intermediate 30 Seconds to Mars - Closer to the edge - 16tel und 8tel Beat 30 Seconds To Mars - From Yesterday https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpG7FzXrNSs 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings and Queens 30 Seconds To Mars - The Kill 311 - Beautiful Disaster - - Intermediate 311 - Dont Stay Home 311 - Guns - Beat ternär - Intermediate 38 Special - Hold On Loosely 4 Non Blondes - Whats Up 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 9-8tel Nine funk Play Along A Ha - Take On Me A Perfect Circle - Judith - 6-8tel 16tel Beat https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTgKRCXybSM A Perfect Circle - The Outsider ABBA - Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA - Mamma Mia - 8tel Beat Beginner ABBA - Super Trouper ABBA - Thank you for the music - 8tel Beat 13 ABBA - Voulez Vous Absolutum Blues - Coverdale and Page ACDC - Back in black ACDC - Big Balls ACDC - Big Gun ACDC - Black Ice ACDC - C.O.D. ACDC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC - Evil Walks ACDC - For Those About To Rock ACDC - Givin' The Dog A Bone ACDC - Go Down ACDC - Hard as a rock ACDC - Have A Drink On Me ACDC - Hells Bells https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFJFonWfBBM ACDC - Highway To Hell ACDC - I Put The Finger On You ACDC - It's A Long Way To The Top ACDC - Let's Get It Up ACDC - Money Made ACDC - Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution ACDC - Rock' n Roll Train ACDC - Shake Your Foundations ACDC - Shoot To Thrill ACDC - Shot Down in Flames ACDC - Stiff Upper Lip ACDC - The -

She Didn't See It Coming

She didn’t see it coming She didn’t see it coming First published July 15, 2018. New edition published May 2019. Please note: story was updated in May 2019 because I wanted to improve I so if you read it before it has changed. Plot remains the same but has been extensively elaborated and full chapters added. 2 She didn’t see it coming About the story Are we really sure Bones died a far too early death for such a charismatic character? Nah, don’t think so. This is my alternative take on Season 3. The story begins during the Bangladesh tour at the end of episode 5, when Bones has just been blown to pieces in front of 2 section at a garden party. I was very unhappy about the turn of events, so out of pure frustration I decided to have try at writing fanfiction. I anyway always have side stories about movie characters I like running in my head, so why not write them down. The past is basically canon. Credits to Tony Grounds and BBC for the characters, I just let them live another life for a while here. The reason I updated eight months after first publishing it, was that at a re-read I realised I could do better and felt that my only full- length Bones & Georgie fic deserved as good as I got. This is a hot story. if you don’t like a bit of smut you may need to skip parts, but above all it is a love story.