Bolstering Urbanization Efforts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solutions for Sustainable Cities

CMYK Logo / State of Green Green C 100 - M 0 - Y 70 - K 0 100% & 60 % Dark C 0 - M 0 - Y 0 - K 95 Copenhagen: Solutions For Sustainable Cities COPENHAGEN January 2014 3rd edition CITY OF COPENHAGEN City Hall 1599 København V SOLUTIONS FOR [email protected] www.cphcleantech.com SUSTAINABLE CITIES CMYK Logo / State of Green Green C 100 - M 0 - Y 70 - K 0 100% & 60 % Dark C 0 - M 0 - Y 0 - K 95 54/55 STATE OF Green – Join the FUTURE. THINK DENMARK Denmark has decided to lead the transition to a Green STATE OF GREEN CONSORTIUM Growth Economy and aims to be independent of fossil fuels The State of Green Consortium is the organisation behind by 2050. As the official green brand for Denmark, State of the official green brand for Denmark. The consortium Green gathers all leading players in the fields of energy, is a public-private partnership founded by the Danish climate, water and environment and fosters relations with Government, the Confederation of Danish Industry, the international stakeholders interested in learning from the Danish Energy Association, the Danish Agriculture & Food Danish experience. Council and the Danish Wind Industry Association. H.R.H. Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark is patron of the State of EXPLORE, LEARN AND CONNECT ONLINE Green Consortium. State of Green’s commercial partners Stateofgreen.com is your online entry point for all relevant are DONG Energy and Danfoss. information on green solutions in Denmark and around the world. Here you can explore solutions, learn about products and connect with profiles. -

Urban Planning and Urban Design

5 Urban Planning and Urban Design Coordinating Lead Author Jeffrey Raven (New York) Lead Authors Brian Stone (Atlanta), Gerald Mills (Dublin), Joel Towers (New York), Lutz Katzschner (Kassel), Mattia Federico Leone (Naples), Pascaline Gaborit (Brussels), Matei Georgescu (Tempe), Maryam Hariri (New York) Contributing Authors James Lee (Shanghai/Boston), Jeffrey LeJava (White Plains), Ayyoob Sharifi (Tsukuba/Paveh), Cristina Visconti (Naples), Andrew Rudd (Nairobi/New York) This chapter should be cited as Raven, J., Stone, B., Mills, G., Towers, J., Katzschner, L., Leone, M., Gaborit, P., Georgescu, M., and Hariri, M. (2018). Urban planning and design. In Rosenzweig, C., W. Solecki, P. Romero-Lankao, S. Mehrotra, S. Dhakal, and S. Ali Ibrahim (eds.), Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press. New York. 139–172 139 ARC3.2 Climate Change and Cities Embedding Climate Change in Urban Key Messages Planning and Urban Design Urban planning and urban design have a critical role to play Integrated climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the global response to climate change. Actions that simul- should form a core element in urban planning and urban design, taneously reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and build taking into account local conditions. This is because decisions resilience to climate risks should be prioritized at all urban on urban form have long-term (>50 years) consequences and scales – metropolitan region, city, district/neighborhood, block, thus strongly affect a city’s capacity to reduce GHG emissions and building. This needs to be done in ways that are responsive and to respond to climate hazards over time. -

2012-Cities-Of-Opportunity.Pdf

Abu Dhabi Hong Kong Madrid New York Singapore Beijing Istanbul Mexico City Paris Stockholm Berlin Johannesburg Milan San Francisco Sydney Buenos Aires Kuala Lumpur Moscow São Paulo Tokyo Chicago London Mumbai Seoul Toronto Los Angeles Shanghai Cities of Opportunity Cities of Opportunity 2012 analyzes the trajectory of 27 cities, all capitals of finance, commerce, and culture—and through their current performance seeks to open a window on what makes cities function best. This year, we also look ahead to 2025 to project employment, production, and population patterns, as well as “what if” scenarios that prepare for turns in the urban road. Cover image: Brooklyn Bridge and Lower Manhattan, Guillaume Gaudet Photography www.pwc.com ©2012 PwC. All rights reserved. “PwC” and “PwC US” refer to PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership, which is a member firm of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each member firm of which is a separate legal entity. This document is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors. www.pfnyc.org ©2012 The Partnership for New York City, Inc. All rights reserved. Looking to the future of 27 cities at the center of the world economy In this fifth edition of Cities of Opportunity, 2.5 percent of the population. By the quarter- with some of this uncertainty, “what if” PwC and the Partnership for New York City century, they will house 19 million more scenarios test the future of our cities under again examine the current social and economic residents, produce 13.7 million additional different conditions. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

Think Clear, Head North Get to Know Us the University In

BE 1* OF THE BEST EXCHANGE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI *We are among the top 1% of the world’s research universities. There are thousands of universities in the world, and the University of Helsinki is proud to be constantly ranked among the top one hundred. According to the latest Times THINK Higher Education World University Ranking, the University of Helsinki retained its position as the best multidisciplinary university in the Nordic countries. We are better than 99.9% CLEAR, of the rest, so by studying with us you can become one of the best too! Diversely open, quality conscious and joyfully serious. HEAD Internationalisation means many things for us, but one thing is sure: as a world-class university we embrace the NORTH presence of international students. HELSINKI.FI/EXCHANGE 40,000 STUDENTS AND RESEARCHERS The University of Helsinki is the oldest and largest THE institution of academic education in Finland. It has an international scientific community of 40,000 students and researchers. UNIVERSITY 4 CAMPUSES AND 11 FACULTIES The university contains 11 faculties, and provides teaching on four campuses in Helsinki: City Centre, Kumpula, Mei- IN BRIEF lahti and Viikki. In addition, the University has research sta- tions in Hyytiälä, Värriö and Kilpisjärvi as well as in Kenya. 180 000 ALUMNI Become part of the global network of 180 000 alumni all over the world. 8200 EMPLOYEES In total, 8200 employees work at the university: 55% of them are teaching and research staff and HELSINKI.FI/EXCHANGE 13% have international roots. -

State of the World2007

THE WORLDWATCH INSTITUTE 20072007 STATESTATE OFOF THETHE WORLDWORLD Our UrbanUrban FuturFuturee 2007 STATE OF THE WORLD Our Urban Future D I GITAL EDITION Please look for the symbol above throughout the chapters for live links to locations in Google Maps. Also, please note that the Table of Contents is clickable, for easier navigation through this PDF. Other Norton/Worldwatch Books State of the World 1984 through 2006 (an annual report on progress toward a sustainable society) Vital Signs 1992 through 2003 and 2005 through 2006 (a report on the trends that are shaping our future) Saving the Planet Who Will Feed China? Beyond Malthus Lester R. Brown Lester R. Brown Lester R. Brown Christopher Flavin Gary Gardner Sandra Postel Tough Choices Brian Halweil Lester R. Brown How Much Is Enough? Pillar of Sand Alan Thein Durning Fighting for Survival Sandra Postel Michael Renner Last Oasis Vanishing Borders Sandra Postel The Natural Wealth of Nations Hilary French Full House David Malin Roodman Eat Here Lester R. Brown Brian Halweil Hal Kane Life Out of Bounds Chris Bright Power Surge Inspiring Progress Christopher Flavin Gary T. Gardner Nicholas Lenssen 2007 STATE OF THE WORLD Our Urban Future A Worldwatch Institute Report on Progress Toward a Sustainable Society Molly O’Meara Sheehan, Project Director Zoë Chafe Danielle Nierenberg Christopher Flavin Janice Perlman Brian Halweil Mark Roseland Kristen Hughes David Satterthwaite Jeff Kenworthy Janet Sawin Kai Lee Lena Soots Lisa Mastny Peter Stair Gordon McGranahan Carolyn Stephens Peter Newman Linda Starke, Editor W . W . N O R TON & COMPANY NEW YORK LONDON Copyright © 2007 by Worldwatch Institute 1776 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. -

Global Geospatial Information Management in Africa Action Plan 2016 - 2030

Global Geospatial Information Management in Africa Action Plan 2016 - 2030 A Call for action to strengthen and sustain national geospatial information systems and infrastructures in a coordinated manner United Nations Economic Commission for Africa ___________________ Geoinformation & UNWGIC Spatial Statistics Deqinq, China ___________________ 21 November 2018 Andre Nonguierma Outlines UN-GGIM Context Why we need Geography? UN-GGIM : African Holistic Geospatial information Vision At its July 2011 substantive The Policy Drivers : Global Need for Spatially- Coordinated approach for cooperative management of session, following extensive Enabled Complex Information Everything that happens, happens somewhere geospatial information that adopts common regional consultation with geospatial standards, frameworks and tools over space and time experts of Member States, the Management of global geospatial information to address 80% of all human decisions involve a “Where?” Economic and Social Council key global challenges including Sustainable development, question climate change, disaster management, peace and (ECOSOC) considered the report You cannot count what you cannot locate security, and environmental stresses of the Secretary General Location affects nearly everything we do in life. Intergovernmental Process where the Member States play (E/2011/89) and adopted a the key role resolution to create the United . Nations Committee of Experts on Geography Nexus Issues Key Pillars Way Forward Global Geospatial Information Availability Key Pillars -

An Unfinished Journey William Minter

An Unfinished Journey William Minter he early morning phone call came on Febru- 1973; Patrice Lumumba in 1961; Malcolm X in 1965; ary 4, 1969, the day after I arrived back from Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968; Steve Biko in 1977; Tanzania to my parents’ house in Tucson, Ruth First in 1982; and Samora Machel in 1986—to Arizona. “Eduardo has been assassinated.” name only a few. TThe caller was Gail Hovey, one of the co-editors Memories of those who gave their lives can bind of this book. She was then working with the South- together and inspire those who carry on their lega- ern Africa Committee in New York, a group sup- cies. So can highly visible public victories, such as porting liberation movements in Mozambique and the dramatic release of Nelson Mandela from prison other Southern African countries. Eduardo, as he in February 1990 and the first democratic election was known to hundreds of friends around the world, in South Africa in April 1994. The worldwide anti- was Eduardo Mondlane. At the time of his death by apartheid movement, which helped win those victo- a letter bomb, he was president of the Mozambique ries, was arguably the most successful transnational Liberation Front, known as Frelimo. Had he lived to social movement of the last half century. All of us see the freedom of his country, he would likely have engaged in this book project were minor actors in joined his contemporary and friend Nelson Mandela that movement, and our roles will become clear as as one of Africa’s most respected leaders. -

The Geography of the Global Super-Rich

THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE GLOBAL SUPER-RICH Cities The Cities Project at the Martin Prosperity Institute focuses on the role of cities as the key economic and social organizing unit of global capitalism. It explores both the opportunities and challenges facing cities as they take on this heightened new role. The Martin Prosperity Institute, housed at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, explores the requisite underpinnings of a democratic capitalist economy that generate prosperity that is both robustly growing and broadly experienced. THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE GLOBAL SUPER-RICH Richard Florida Charlotta Mellander Isabel Ritchie Contents Executive Summary 6 Introduction 8 Mapping the Global Super-Rich 10 Mapping the Wealth of the Global Super-Rich 14 Mapping the Average Net Worth of the Super-Rich 16 The Spiky Geography of the Super-Rich 18 What Factors Account for the Geography of the Super-Rich 22 Self-Made versus Inherited Wealth 30 Mapping the Super-Rich by Industry 33 The Super-Rich and Inequality 39 Conclusion 41 Appendix: Data, Variables, and Methodology 42 References 44 About the Authors 46 4 The Geography of the Global Super-Rich Exhibits Exhibit 1 Billionaires by Country 10 Exhibit 2 Top 20 Countries for the Super-Rich 11 Exhibit 3 The Global Super-Rich by Major Global City and Metro 12 Exhibit 4 Top 20 Metros of the Global Super-Rich 13 Exhibit 5 Super-Rich Fortunes by Global City or Metro 14 Exhibit 6 Top 10 Global Cities for Billionaire Wealth 15 Exhibit 7 Average Billionaire Net Worth by Global City or Metro 16 -

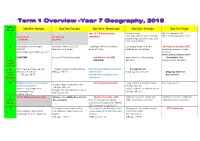

Term 1 Overview -Year 7 Geography, 2018

Term 1 Overview -Year 7 Geography, 2018 Term 1 Day One: Monday Day Two: Tuesday Day Three: Wednesday Day Four: Thursday Day Five: Friday Week 1 Year 12, 7 & New Students e-Book access What is Geography? “Getting to know you” activities What do Geographers do? No Students No Students Commence Establishing classroom rules and STAFF PD STAFF PD HASS expectations 2 Geographical concepts: Features of Maps: BOLTSS Getting to know your Atlas Locating places on maps Opening school Mass (MT) SPICESS Direction and Scale Types of maps Latitude and Longitude Locating places on maps Oxford Big Ideas (OBI) pgs. 6-11 Activities Inform students about test wk 4 3 DANCING Area and Grid referencing Ash Wednesday (MT) Area and Grid referencing Revision for test Lower DANCING Activities Mapping skills Activities school dancing 4 Why we live where we do? Where modern Australians live Push and pull factors for human Revision for test Senior What is liveability? OBI pgs 130-131 settlements? Mapping skills Activities Mapping Skills Test school OBI pgs. 94-95 Environments conductive to Assessment 1 Dancing settlement 5 Historical context of Australia’s JPC Swimming Carnival Living in Rural Australian areas Catch up lesson Living in large Australian Cities settlement patterns OBI Pgs.134-135 OBI Pgs. 132-133 Where early Indigenous Living in remote Australian areas Living in Coastal Australian areas. Australians lived OBI Pgs.138-139 OBI Pg 136-137 OBI pg 126-127 6 Public Holiday (Labour Day) Introduce Liveability Assessment Modified Timetable (MT) Walking excursion- Kalgoorlie Walking excursion- Kalgoorlie Clancy Assessment 2 How to measure liveability : CBD/ assessment- Lesson 1 CBD/assessment- Lesson 2 Week objective and subjective factors OBI Chapter 3.2 pgs 96-107 7 The world’s most livable cities: The world’s least liveable cities: Melbourne “the most liveable ACC Swimming Preparing for assessment: Case Studies: Vancouver and Case studies: Port Moresby and city in the world” collating info from fieldwork Vienna Harare How and why? OBI pgs. -

Washington Notes on Africa, Jan. 1969

Washington notes on Africa, Jan. 1969 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.acoa000001 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Washington notes on Africa, Jan. 1969 Alternative title Washington notes on Africa Author/Creator American Committee on Africa (ACOA) Contributor Gappert, Gary Publisher American Committee on Africa (ACOA) Date 1969-01 Resource type Newsletters Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, United States, Nigeria Coverage (temporal) 1968 - 1969 Source Africa Action Archive Rights By kind permission of Africa Action, incorporating the American Committee on Africa, The Africa Fund, and the Africa Policy Information Center. -

General Assembly 5 August 2016

United Nations A/RES/70/293 Distr.: General General Assembly 5 August 2016 Seventieth session Agenda item 15 Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 July 2016 [without reference to a Main Committee (A/70/L.49/Rev.1)] 70/293. Third Industrial Development Decade for Africa (2016–2025) The General Assembly, Recalling its resolution 35/66 B of 5 December 1980, in which it proclaimed the 1980s as the first Industrial Development Decade for Africa, its resolution 44/237 of 22 December 1989, in which it proclaimed the period 1991–2000 as the Second Industrial Development Decade for Africa, its resolution 47/177 of 22 December 1992, in which it adjusted the period for the programme for the Second Decade to cover the years 1993–2002, and its resolution 57/297 of 20 December 2002 on the Second Decade, Recalling also its resolution 70/1 of 25 September 2015, entitled “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, which reflects the importance of industrial development to the 2030 Agenda, including Sustainable Development Goal 9, Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation, and its interrelated targets, Recalling further its resolution 69/313 of 27 July 2015 on the Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, which is an integral part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, supports and complements it and helps to contextualize its means of implementation targets with concrete policies and actions,