State of the World2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solutions for Sustainable Cities

CMYK Logo / State of Green Green C 100 - M 0 - Y 70 - K 0 100% & 60 % Dark C 0 - M 0 - Y 0 - K 95 Copenhagen: Solutions For Sustainable Cities COPENHAGEN January 2014 3rd edition CITY OF COPENHAGEN City Hall 1599 København V SOLUTIONS FOR [email protected] www.cphcleantech.com SUSTAINABLE CITIES CMYK Logo / State of Green Green C 100 - M 0 - Y 70 - K 0 100% & 60 % Dark C 0 - M 0 - Y 0 - K 95 54/55 STATE OF Green – Join the FUTURE. THINK DENMARK Denmark has decided to lead the transition to a Green STATE OF GREEN CONSORTIUM Growth Economy and aims to be independent of fossil fuels The State of Green Consortium is the organisation behind by 2050. As the official green brand for Denmark, State of the official green brand for Denmark. The consortium Green gathers all leading players in the fields of energy, is a public-private partnership founded by the Danish climate, water and environment and fosters relations with Government, the Confederation of Danish Industry, the international stakeholders interested in learning from the Danish Energy Association, the Danish Agriculture & Food Danish experience. Council and the Danish Wind Industry Association. H.R.H. Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark is patron of the State of EXPLORE, LEARN AND CONNECT ONLINE Green Consortium. State of Green’s commercial partners Stateofgreen.com is your online entry point for all relevant are DONG Energy and Danfoss. information on green solutions in Denmark and around the world. Here you can explore solutions, learn about products and connect with profiles. -

Urban Planning and Urban Design

5 Urban Planning and Urban Design Coordinating Lead Author Jeffrey Raven (New York) Lead Authors Brian Stone (Atlanta), Gerald Mills (Dublin), Joel Towers (New York), Lutz Katzschner (Kassel), Mattia Federico Leone (Naples), Pascaline Gaborit (Brussels), Matei Georgescu (Tempe), Maryam Hariri (New York) Contributing Authors James Lee (Shanghai/Boston), Jeffrey LeJava (White Plains), Ayyoob Sharifi (Tsukuba/Paveh), Cristina Visconti (Naples), Andrew Rudd (Nairobi/New York) This chapter should be cited as Raven, J., Stone, B., Mills, G., Towers, J., Katzschner, L., Leone, M., Gaborit, P., Georgescu, M., and Hariri, M. (2018). Urban planning and design. In Rosenzweig, C., W. Solecki, P. Romero-Lankao, S. Mehrotra, S. Dhakal, and S. Ali Ibrahim (eds.), Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press. New York. 139–172 139 ARC3.2 Climate Change and Cities Embedding Climate Change in Urban Key Messages Planning and Urban Design Urban planning and urban design have a critical role to play Integrated climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the global response to climate change. Actions that simul- should form a core element in urban planning and urban design, taneously reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and build taking into account local conditions. This is because decisions resilience to climate risks should be prioritized at all urban on urban form have long-term (>50 years) consequences and scales – metropolitan region, city, district/neighborhood, block, thus strongly affect a city’s capacity to reduce GHG emissions and building. This needs to be done in ways that are responsive and to respond to climate hazards over time. -

2012-Cities-Of-Opportunity.Pdf

Abu Dhabi Hong Kong Madrid New York Singapore Beijing Istanbul Mexico City Paris Stockholm Berlin Johannesburg Milan San Francisco Sydney Buenos Aires Kuala Lumpur Moscow São Paulo Tokyo Chicago London Mumbai Seoul Toronto Los Angeles Shanghai Cities of Opportunity Cities of Opportunity 2012 analyzes the trajectory of 27 cities, all capitals of finance, commerce, and culture—and through their current performance seeks to open a window on what makes cities function best. This year, we also look ahead to 2025 to project employment, production, and population patterns, as well as “what if” scenarios that prepare for turns in the urban road. Cover image: Brooklyn Bridge and Lower Manhattan, Guillaume Gaudet Photography www.pwc.com ©2012 PwC. All rights reserved. “PwC” and “PwC US” refer to PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership, which is a member firm of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each member firm of which is a separate legal entity. This document is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors. www.pfnyc.org ©2012 The Partnership for New York City, Inc. All rights reserved. Looking to the future of 27 cities at the center of the world economy In this fifth edition of Cities of Opportunity, 2.5 percent of the population. By the quarter- with some of this uncertainty, “what if” PwC and the Partnership for New York City century, they will house 19 million more scenarios test the future of our cities under again examine the current social and economic residents, produce 13.7 million additional different conditions. -

Think Clear, Head North Get to Know Us the University In

BE 1* OF THE BEST EXCHANGE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI *We are among the top 1% of the world’s research universities. There are thousands of universities in the world, and the University of Helsinki is proud to be constantly ranked among the top one hundred. According to the latest Times THINK Higher Education World University Ranking, the University of Helsinki retained its position as the best multidisciplinary university in the Nordic countries. We are better than 99.9% CLEAR, of the rest, so by studying with us you can become one of the best too! Diversely open, quality conscious and joyfully serious. HEAD Internationalisation means many things for us, but one thing is sure: as a world-class university we embrace the NORTH presence of international students. HELSINKI.FI/EXCHANGE 40,000 STUDENTS AND RESEARCHERS The University of Helsinki is the oldest and largest THE institution of academic education in Finland. It has an international scientific community of 40,000 students and researchers. UNIVERSITY 4 CAMPUSES AND 11 FACULTIES The university contains 11 faculties, and provides teaching on four campuses in Helsinki: City Centre, Kumpula, Mei- IN BRIEF lahti and Viikki. In addition, the University has research sta- tions in Hyytiälä, Värriö and Kilpisjärvi as well as in Kenya. 180 000 ALUMNI Become part of the global network of 180 000 alumni all over the world. 8200 EMPLOYEES In total, 8200 employees work at the university: 55% of them are teaching and research staff and HELSINKI.FI/EXCHANGE 13% have international roots. -

The Geography of the Global Super-Rich

THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE GLOBAL SUPER-RICH Cities The Cities Project at the Martin Prosperity Institute focuses on the role of cities as the key economic and social organizing unit of global capitalism. It explores both the opportunities and challenges facing cities as they take on this heightened new role. The Martin Prosperity Institute, housed at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, explores the requisite underpinnings of a democratic capitalist economy that generate prosperity that is both robustly growing and broadly experienced. THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE GLOBAL SUPER-RICH Richard Florida Charlotta Mellander Isabel Ritchie Contents Executive Summary 6 Introduction 8 Mapping the Global Super-Rich 10 Mapping the Wealth of the Global Super-Rich 14 Mapping the Average Net Worth of the Super-Rich 16 The Spiky Geography of the Super-Rich 18 What Factors Account for the Geography of the Super-Rich 22 Self-Made versus Inherited Wealth 30 Mapping the Super-Rich by Industry 33 The Super-Rich and Inequality 39 Conclusion 41 Appendix: Data, Variables, and Methodology 42 References 44 About the Authors 46 4 The Geography of the Global Super-Rich Exhibits Exhibit 1 Billionaires by Country 10 Exhibit 2 Top 20 Countries for the Super-Rich 11 Exhibit 3 The Global Super-Rich by Major Global City and Metro 12 Exhibit 4 Top 20 Metros of the Global Super-Rich 13 Exhibit 5 Super-Rich Fortunes by Global City or Metro 14 Exhibit 6 Top 10 Global Cities for Billionaire Wealth 15 Exhibit 7 Average Billionaire Net Worth by Global City or Metro 16 -

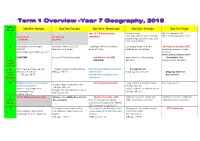

Term 1 Overview -Year 7 Geography, 2018

Term 1 Overview -Year 7 Geography, 2018 Term 1 Day One: Monday Day Two: Tuesday Day Three: Wednesday Day Four: Thursday Day Five: Friday Week 1 Year 12, 7 & New Students e-Book access What is Geography? “Getting to know you” activities What do Geographers do? No Students No Students Commence Establishing classroom rules and STAFF PD STAFF PD HASS expectations 2 Geographical concepts: Features of Maps: BOLTSS Getting to know your Atlas Locating places on maps Opening school Mass (MT) SPICESS Direction and Scale Types of maps Latitude and Longitude Locating places on maps Oxford Big Ideas (OBI) pgs. 6-11 Activities Inform students about test wk 4 3 DANCING Area and Grid referencing Ash Wednesday (MT) Area and Grid referencing Revision for test Lower DANCING Activities Mapping skills Activities school dancing 4 Why we live where we do? Where modern Australians live Push and pull factors for human Revision for test Senior What is liveability? OBI pgs 130-131 settlements? Mapping skills Activities Mapping Skills Test school OBI pgs. 94-95 Environments conductive to Assessment 1 Dancing settlement 5 Historical context of Australia’s JPC Swimming Carnival Living in Rural Australian areas Catch up lesson Living in large Australian Cities settlement patterns OBI Pgs.134-135 OBI Pgs. 132-133 Where early Indigenous Living in remote Australian areas Living in Coastal Australian areas. Australians lived OBI Pgs.138-139 OBI Pg 136-137 OBI pg 126-127 6 Public Holiday (Labour Day) Introduce Liveability Assessment Modified Timetable (MT) Walking excursion- Kalgoorlie Walking excursion- Kalgoorlie Clancy Assessment 2 How to measure liveability : CBD/ assessment- Lesson 1 CBD/assessment- Lesson 2 Week objective and subjective factors OBI Chapter 3.2 pgs 96-107 7 The world’s most livable cities: The world’s least liveable cities: Melbourne “the most liveable ACC Swimming Preparing for assessment: Case Studies: Vancouver and Case studies: Port Moresby and city in the world” collating info from fieldwork Vienna Harare How and why? OBI pgs. -

Reinvigorating Springfield's Economy: Lessons from Resurgent Cities

Towards a More Prosperous Springfield, MA: What Jobs Exist for People without a College Education? Reinvigorating Springfield’s Economy: Lessons from Resurgent Cities Yolanda K. Kodrzycki and Ana Patricia Muñoz with Lynn Browne, DeAnna Green, Marques Benton, Prabal Chakrabarti, David Plasse, Richard Walker, and Bo Zhao COMMUNITY AFFAIRS DISCUSSIONAugust PAPER 2009 ▪ 2009-03No. 2009-03 ▪ i Reinvigorating Springfield's Economy: Lessons from Resurgent Cities Reinvigorating Springfield’s Economy: Lessons from Resurgent Cities Yolanda K. Kodrzycki and Ana Patricia Muñoz with Lynn Browne, DeAnna Green, Marques Benton, Prabal Chakrabarti, David Plasse, Richard Walker, Bo Zhao August 11, 2009 ABSTRACT: As part of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s commitment to supporting efforts to revitalize the economy of Springfield, Massachusetts, this paper analyzes the economic development approaches of other mid‐sized manufacturing‐oriented cities during the past half century. From among a comparison group of 25 municipalities that were similar to Springfield in 1960, the study identifies 10 “resurgent cities” that have made substantial progress in improving living standards for their residents, and that are recognized as vital communities in a broader sense by experts on urban economic development and policy. These case studies suggest that industry mix, demographic composition, and geographic position are not the key factors distinguishing the resurgent cities from Springfield. Instead, the most important lessons from the resurgent cities concern leadership and collaboration. Initial leadership in these cities came from a variety of key institutions and individuals. In some cases, the turnaround started with efforts on the part of the public sector, while in other cases nongovernmental institutions or private developers were at the forefront. -

100% Renewables, Zero Poverty REPORT PREFACE

Joint Report 2015 Are You In? 100% Renewables, Zero Poverty REPORT PREFACE In September 2015 world leaders signed off on a new global 15 year plan to tackle poverty inequality and climate change. In doing so, 1.2 billion they pledged to ensure all people have access to affordable, reliable, people, sustainable and modern energy. Today 1.2 billion people (nearly 1 in 7) lack access to electricity. But communities are rolling out renewables in order to beat back poverty, as these technologies can provide sustainable energy access where coal, oil and gas have failed for the last century. Sustainable energy can improve health by reducing pollution, it can improve edu- cation, create jobs and kickstart industries in minor economies. There is already a growing movement of leaders from villages, cities and businesses around the world who are not waiting for national governments to act, but are getting their own communities on track to a 100% renewable energy powered future - to deliver the just, equitable, healthy and prosperous world we need. This report features a range of these people whose stories high- light the development benefits derived from getting on track to go 100% renewable. For example, take Marjina from Bangladesh, one of the real world leaders featured in this report. Marjina faced ener- gy poverty, a lack of reliable energy access, that was exacerbating gender inequality in her village. Women were unable to walk safely down unlit streets until Marjina harnessed the power of renewable energy to light the way for her daughters today and into the future. What’s not evident from Marjina’s story is that this kind of action will also, eventually, limit the climate impacts these communities are projected to experience, the kind of impacts that are stripping away the hard won development gains made in recent years. -

Vancouver: Significant Achievements; Significant Opportunities to Be Even Better

Vancouver: Significant Achievements; Significant Opportunities to Be Even Better A Talk by Michael A. Goldberg to the Urban Land Institute Town Hall Session Spring 2014 Meeting, Thursday, 10th April 2014 Vancouver, BC #ULISpring14 Introduction •Vancouver began as int’l city •Century later in we hit global stage via •EXPO ’86 – our 100th birthday party •Asia Pacific Inititiative1987 Genesis of YVR “privatization” •Vancouver’s successes and opportunities foci here #ULISpring14 Overview of discussion • Presentation examines – Vancouver’s successes – Current and future opportunities – Chief among these are • Being economically competitive • Integrating economic and land use strategies • Integrating transportation and land use • Enhancing experience/enjoyment of the city #ULISpring14 Some natural assets • We’re beautiful - super place to live • Diverse multi-cultural society • Time zone between Europe and Asia • On great circle route from West Coast to Asia • Relatively mild climate w/great summers • Abundant high quality diverse natural capital and resources #ULISpring14 Some developed assets • Gateway efforts tie us globally –YVR best airport on continent 5 years running –Port Metro Vancouver biggest in Canada, 4th on continent • Universities/educational system very strong • Parks, recreation, cultural resources first rate • Tourism, culture, architecture/engineering global • New media, IT and biotech sectors vibrant • Populating downtown and opening 3 waterfronts • $9+ billion investment in 4 rapid transit lines #ULISpring14 Current challenges -

Livability Index a Comparison of the Quality of Life Across NYC’S Community Districts to Help Community Boards Better Serve Their Residents

Livability Index A comparison of the Quality of Life across NYC’s Community Districts to help Community Boards better serve their residents Manhattan Community Board 1 May 2017 Livability Index May 2017 Acknowledgements I, Jahnavi Aluri, would like to thank everyone who made this report possible. First and foremost, I want to extend my gratitude to the Manhattan Community Board 1 Staff for their guidance, patience, support, and good humor: • Diana Switaj, Director of Planning and Land Use • Michael Levine, Planning Consultant • Lucy Acevedo, Community Coordinator • Noah Pfefferblit, District Manager This project would not have been possible without the vision of the Manhattan Community Board 1 Officers and Members. I would especially like to thank the Chairperson for championing this study and for his encouragement: • Anthony Notaro, Chairperson Finally, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to the Fund for the City of New York (FCNY) for developing the Community Planning Fellowship Program. Manhattan Community Board 1 1 Livability Index May 2017 Abstract This study identifies the factors that affect Quality of Life of residents in NYC neighborhoods and measures this Quality of Life on a scale, and compares the Quality of Life across different NYC neighborhoods through the Livability Index to help Community Boards better serve their residents by improving service delivery to address those issues that have been identified through this comparison. Author: Jahnavi Aluri, FCNY Fellow 2016-2017 from Columbia University GSAPP Prepared -

Energy Recovery: a Viable Resource Management Option

Energy Recovery A Viable Resource Management Option Jeff Wooster Plastics Sustainability Leader The Dow Chemical Company April 25, 2011 1 Terminology Matters ‘Waste’ Management vs Resource Management Energy from ‘Waste’ (EFW) ‘Waste’ to Energy (WTE) vs Energy Recovery ‘Waste’ ‘Post‐consumer Packaging’ “something rejected, worthless, A previously used resource which . of no value” vs still has value Packaging is not a waste 2 Packaging is a valuable resource Extends shelf life • Prevents food spoilage • So less people go hungry • So we ship less frequently • Consume less resources • Generate less emissions • Reduce impact of climate change Protects against product theft and damage Fosters a safer and healthier society Facilitates economic development 3 Landfills are Not the Answer Wasting Valuable Visual Pollution Energy High $ Costs Water table ‐ Tipping Fees Contamination Landfills ‐ Shipping Limited Space Chemical Instability Number of Landfills in U.S. 1988-2007 9000 Methane Emissions 7924 8000 7379 78% Reduction in 19 yrs 7000 6326 5812 (‐ 6,170 landfills) 6000 5386 5000 4482 4000 3558 3197 3091 3000 2514 2314 2216 1967 1858 1767 1754 1754 1754 2000 1000 0 ’88135791 ’89 ’90 ’91 ’92 ’93 ’94 ’95 ’96 ’97 ’9811 ’99 ’0031 ’01 ’0251 ’03 ’0471 ’05 ’069 ‘074 Mechanical Recycling is a Major Part of the Solution ‐ But has Limitations Technical – Foodservice ware Unrealistic to expect – Multi‐layer packaging mechanical recycling – Difficult to show material codes alone will meet the on all materials required diversion goals Costs – Collection, -

Global Sustainability Reporting and Discuss the Importance of Charitable and Philanthropic Efforts in Addressing World Issues

2013 Sustainability Report Managing complexity, building better lives. 2 2013 Sustainability Report AECOM Contents About this report ....................................................3 Projects ................................................................19 Global Reporting Initiative .................................... 3 Port of Los Angeles — A waterfront revived .........19 Profile and economic impact ................................. 3 Strumosa Urban Agriculture and Waste Purpose and core values ........................................ 3 Drop-off Centre — Maximizing “green gold” Fiscal year 2013 highlights .....................................4 for job creation .................................................... 21 The community ..................................................... 4 Townsville Port Access Road — Driving the Our culture ............................................................ 4 three pillars of sustainability ............................... 22 Environmental impact ........................................... 5 Livvi’s Place — Making cities more livable .......... 23 Engineering and development ............................... 5 A message from our Weishan Lake Wetland Park — Expanding the President and CEO ..................................................6 Earth’s kidneys .................................................... 24 Eicher Group and VECV Headquarters — Perspectives from our Improving work life quality ................................... 26 Chief Sustainability Officer ....................................7