SC. CHC (APP) No. 30/2003 1 in the SUPREME COURT of THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Job Loss Far Worse Than Indicated

OPPOSITION TO MOVE COURT POLITICAL MATURITY OF OVER PARLIAMENT RECALL SRI LANKA'S LEADERS PUT TO THE TEST MAY THE POWER 01 - 03, 2020 OF PAPER VOL: 4- ISSUE 193 . 30 ‘UTTER DISASTER' PASSIONS AND GLOCAL PAGE 03 HOT TOPICS PAGE 04 COMMENTARY PAGE 06 PERSONALITIES PAGE 08 Registered in the Department of Posts of Sri Lanka under No: QD/144/News/2020 COVID-19 and curfew in Sri Lanka • 14 people were confirmed as COVID-19 positive yester- day (April 30), taking Sri Lanka’s tally of the novel coro- navirus infection to 663. 502 individuals are receiving treatment, 154 have been deemed completely recovered and seven have succumbed to the virus. • An all island curfew was imposed from 8:00 p.m. yes- terday till 5:00 a.m. Monday (4). • Of the 997 navy personnel tested for COVID-19, 159 were confirmed as positive with 80% being asympto- matic. • Of the 21,000 PCR tests carried out in Sri Lanka so far, 3% have been confirmed as positive. • The Civil Aviation Authority has invited drone opera- tors to join the fight against COVID-19. • Police say no decision has been taken so far to extend the curfew in areas deemed as high risk, till May 31 though it was announced that curfew passes issued for essential services that ended yesterday could be used till the end of May. • Postmaster General RanjithAriyaratne has announced that all post offices will be opened from Monday for reg- ular services. He has requested public to follow health advices when visiting post offices and obtaining services. -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999 INTRODUCTION This union list updates African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries compiled by Daniel A. Britz, Working Paper no. 8 African Studies Center, Boston, 1979. The holdings of 19 collections and the Foreign Newspapers Microfilm Project were surveyed during the summer of 1999. Material collected currently by Library of Congress, Nairobi (marked DLC#) is separated from the material which Nairobi sends to Library of Congress in Washington. The decision was made to exclude North African papers. These are included in Middle Eastern lists and in many of the reporting libraries entirely separate division handles them. Criteria for inclusion of titles on this list were basically in accord with the UNESCO definition of general interest newspapers. However, a number of titles were included that do not clearly fit into this definition such as religious newspapers from Southern Africa, and labor union and political party papers. Daily and less frequently published newspapers have been included. Frequency is noted when known. Sunday editions are listed separately only if the name of the Sunday edition is completely different from the weekday edition or if libraries take only the Sunday or only the weekday edition. Microfilm titles are included when known. Some titles may be included by one library, which in other libraries are listed as serials and, therefore, not recorded. In addition to enabling researchers to locate African newspapers, this list can be used to rationalize African newspaper subscriptions of American libraries. It is hoped that this list will both help in the identification of gaps and allow for some economy where there is substantial duplication. -

Family Planning in Ceylon1

1 [This book chapter authored by Shelton Upatissa Kodikara, was transcribed by Dr. Sachi Sri Kantha, Tokyo, from the original text for digital preservation, on July 20, 2021.] FAMILY PLANNING IN CEYLON1 by S.U. Kodikara Chapter in: The Politics of Family Planning in the Third World, edited by T.E.Smith, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1973, pp 291-334. Note by Sachi: I provide foot note 1, at the beginning, as it appears in the published form. The remaining foot notes 2 – 235 are transcribed at the end of the article. The dots and words in italics, that appear in the text are as in the original. No deletions are made during transcription. Three tables which accompany the article are scanned separately and provided. Table 1: Ceylon: population growth, 1871-1971. Table 2: National Family Planning Programme: number of clinics and clinic-population ratio by Superintendent of Health Service (SHS) Area, 1968-9. Table 3: Ceylon: births, deaths and natural increase per 1000 persons living, by ethnic group. The Table numbers in the scans, appear as they are published in the book; Table XII, Table XIII and Table XIV. These are NOT altered in the transcribed text. Foot Note 1: In this chapter the following abbreviations are used: FPA, Family 2 Planning Association, LSSP, Lanka Samasamaja Party, MOH, Medical Officer of Health, SLFP, Sri Lanka Freedom Party; SHS, Superintendent of Health Services; UNP, United National Party. Article Proper The population of Ceylon has grown rapidly over the last 100 years, increasing more than four-fold between 1871 and 1971. -

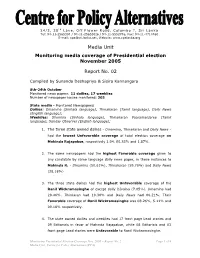

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

Daily Express 20042020

EUROPE VIRUS TOLL TOPS 100,000 GOVT. BANS A WIDE AN INSIDER CALLS MONDAY AS ONLINE MEGA-CONCERT RANGE OF IMPORTS AMID FOR HELP APRIL 20, 2020 RAISES SPIRITS CORONAVIRUS CRISIS VOL: 4 - ISSUE 346 HOT TOPICS PAGE 04 COMMENTARY 30. PAGE 02 PAGE 03 GLOCAL Registered in the Department of Posts of Sri Lanka under No: QD/146/News/2020 COVID-19 and curfew in Sri Lanka • 15 more patients were confirmed as COVID-19 positive yesterday (19), taking Sri Lanka’s tally of the novel coro- navirus infection to 269. One hundred and fifty six indi- viduals are receiving treatment, 122 are under observation, 91 have been deemed completely recovered and seven have succumbed to the virus. • The 24-hour indefinite curfew in 19 out of the 25 districts will be removed at dawn today (20), replaced by a nine- hour night curfew (8:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m.). -Six districts, including Colombo, Gampaha, Kalutara, Put- talam, Ampara and Kandy will see lockdown measures re- laxed from Wednesday (22), but night curfews will be im- posed until further notice. • A ban on public meetings, religious gatherings and pro- cessions will remain, with schools and universities closed until further notice. • Those with suspected COVID-19 symptoms are urged to call 1390 - emergency hotline- set up for free medical ad- vice and assistance, and to facilitate hospital admissions. • Sri Lanka College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has set up a 24-hours hotline – 0710301225- for pregnant women to address issues faced by them including COV- ID-19 infection and pregnancy related complications. -

Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers

Winona State University OpenRiver Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers 11-16-1962 Winona Daily News Winona Daily News Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews Recommended Citation Winona Daily News, "Winona Daily News" (1962). Winona Daily News. 325. https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews/325 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Winona City Newspapers at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in Winona Daily News by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cloudy, Scattered Snow Flurries Tonight, Saturday Will Shoot Down U.S. Planes, Castro Says Kennedy Will Fully Fueled Relations With Cuba Saturn Tested Insist Upon Approaching Climax Surveillance At Canaveral BULLETIN By JOHN fWHIGHTOWE R making clear that the United viet Union has based in Cuba. By HOWARD BENEDICT WASHINGTON < API-Officials States will use force if necessary Antiaircraft missile . fire presum- WASHINGTON Wi — Presl- CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) said today the Cuban crisis may to protect its reconnaissance ably would require a decision by dent Kennedy met with hit —With a mighty roar of its eight be approaching a peak of extreme planes flying over Cuba , in the the President whether to attack top military ami diplomatic engines, a Saturn superbobster danger. In any case, they are now face of a new threat by Fidel Cas- missile bases and put them out of advisers today amid evidence blasted off today on the third test convinced that a climactic period tro to shoot them down. action.; V that Hie Cuban crisis may be flight of this forerunner to a opening in the next . -

Media-Sustainability-Index-Asia-2019-Sri-Lanka.Pdf

SRI LANKA MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2019 Tracking Development of Sustainable Independent Media Around the World MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2019 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in Sri Lanka www.irex.org/msi Copyright © 2019 by IREX IREX 1275 K Street, NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20005 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (202) 628-8188 Fax: (202) 628-8189 www.irex.org Managing editor: Linda Trail Study author: Zahrah Imtiaz, Sri Lanka Development Journalist Forum IREX Editing Support: M. C. Rasmin; Stephanie Hess Design and layout: Anna Zvarych; AURAS Design Inc. Notice of Rights: Permission is granted to display, copy, and distribute the MSI in whole or in part, provided that: (a) the materials are used with the acknowledgement “The Media Sustainability Index (MSI) is a product of IREX.”; (b) the MSI is used solely for personal, noncommercial, or informational use; and (c) no modifications of the MSI are made. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the panelists and other project researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, IREX, or Sri Lanka Development Journalist Forum. The 2019 Sri Lanka MSI was funded by IREX; it was produced as part of the Media Empowerment for a Democratic Sri Lanka program, funded by USAID and made possible by the support of the American people. ISSN 1546-0878 IREX Sri Lanka Development Journalist Forum IREX is a nonprofit organization that builds a more just, prosperous, and inclusive world Sri Lanka Development Journalist Forum (SDJF) is a well-established national level by empowering youth, cultivating leaders, strengthening institutions, and extending organization, with more than 7 years of experience in promoting the role of media in access to quality education and information. -

PDF995, Job 7

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara First week from nomination: 8th-15th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 94 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); • The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.14, 00% and 1.82%. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda Rajapakse. - Dinamina (43.56%), Thinakaran (56.21%) and Daily News (29.32%). • The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe, of any daily news paper. Dinamina had 28.82%. Thinkaran had 8.67% and Daily News had 12.64%. • Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe, was 10.75%, 5.10% and 11.13% respectively. • The state owned dailies and weeklies had 04 front page Lead stories and 02 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 02 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. State media coverage of two main candidates (in sq.cm% of total election coverage) Mahinda Rajapakshe Ranil W ickramasinghe Newspaper Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable Dinamina 43.56 1.14 10.75 28.88 Silumina 28.82 10.65 18.41 30.65 Daily news 29.22 1.82 11.13 12.64 Sunday Observer 23.24 00 12.88 00.81 Thinakaran 56.21 00 03.41 00.43 Thi. -

TITLE a Report on the Activities of the First Five Years, 1963-1968

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 827 AC 008 547 TITLE A Report on the Activities of the First Five Years, 1963-1968. INSTITUTION Thompson Foundation, London (England). PUB DATE [69] NOTE 34p.; photos EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$1.80 DESCRIPTORS Admission Criteria, Audiovisual Aids, Capital Outlay (for Fixed Assets), Curriculum, Developing Nations, Expenditure Per Student, Foreign Nationals, Grants, *Inservice Education, Instructional Staff, *Journalism, Physical Facilities, *Production Techniques, Students, *Television IDENTIFIERS Great Britain ABSTRACT The Thomson Foundation trains journalists and television producers and engineers from developing nations in order to help these nations use mass communication techniques in education. Applicants must be fluent in English; moreover, their employers must certify that the applicants merit overseas training and will return to their work after training. Scholarships cover most expenses other than travel to and from the United Kingdom. Three 12-week courses covering such topics as news editing, reporting, features, photography, agricultural journalism, management, and press freedoms, are held annually at the Thomson Foundation Editorial Study Centre in Cardiff; two 16-week courses are held on various aspects of engineering and program production at the Television College, Glasgow. During vacation periods, the centers offer workshops and other inservice training opportunities to outside groups.(The document includes the evolution of the programs, trustee and staff rosters, Foundation grants, capital and per capita costs, overseas visits and cumulative list of students from 68 countries.) (LY) A REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE FIRST FIVE YEARS 1963/1968 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. -

A Case Study of Sri Lankan Media

C olonials, bourgeoisies and media dynasties: A case study of Sri Lankan media. Abstract: Despite enjoying nearly two centuries of news media, Sri Lanka has been slow to adopt western liberalist concepts of free media, and the print medium which has been the dominant format of news has remained largely in the hands of a select few – essentially three major newspaper groups related to each other by blood or marriage. However the arrival of television and the change in electronic media ownership laws have enabled a number of ‘independent’ actors to enter the Sri Lankan media scene. The newcomers have thus been able to challenge the traditional and incestuous bourgeois hold on media control and agenda setting. This paper outlines the development of news media in Sri Lanka, and attempts to trace the changes in the media ownership and audience. It follows the development of media from the establishment of the first state-sanctioned newspaper to the budding FM radio stations that appear to have achieved the seemingly impossible – namely snatching media control from the Wijewardene, Senanayake, Jayawardene, Wickremasinghe, Bandaranaike bourgeoisie family nexus. Linda Brady Central Queensland University ejournalist.au.com©2005 Central Queensland University 1 Introduction: Media as an imprint on the tapestry of Ceylonese political evolution. The former British colony of Ceylon has a long history of media, dating back to the publication of the first Dutch Prayer Book in 1737 - under the patronage of Ceylon’s Dutch governor Gustaaf Willem Baron van Imhoff (1736-39), and the advent of the ‘newspaper’ by the British in 1833. By the 1920’s the island nation was finding strength as a pioneer in Asian radio but subsequently became a relative latecomer to television by the time it was introduced to the island in the late1970’s. -

Newspaper Reporting of Suicide Impact on Rate of Suicide in the Contemporary Society in Sri Lanka*

Journalism and Mass Communication, May 2016, Vol. 6, No. 5, 237-255 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2016.05.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Newspaper Reporting of Suicide Impact on Rate of Suicide in the Contemporary Society in Sri Lanka* Manoj Jinadasa University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya, Sri Lanka Suicide has been largely investigated by many researchers in a variety of perspectives. The objective of this study is to identify the relationship between the rate of suicide in contemporary society and how it can be affected by the way of suicide reporting at the same time. Qualitative method is used to analysis the data capturing from observation, interviews and textual analysis. Special attention has been paid to the news reporting in the suicide in Sri Lankan newspapers. Sinhala medium newspapers: Lankadeepa, Diwaina, Lakbima, Silumina, Dinamina, Rivira, were used as the major sample of this study. Time period is located from January 2000 to January 2010. In conclusion, Suicide has been reporting in Sri Lanka as a heroic and sensational action for the target of maximum selling and the financial benefit of media institutions. Use of Language in suicide reporting and the placement of the story in the newspaper have been two major factors that cause to glamorize the incident. Suicide reporting is highly sensational and rhetorically made by the ownership of the media and non-ethical consideration of the journalism in Sri Lanka. Victims and vulnerable are encouraged to get in to suicide and they are generally encouraged to their action for faith. Suicide should be reported in the newspaper as a problem of mental health and attention should be drawn to well inform the public on the issue.