An Agenda for Change the Right to Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media Performance in Sri Lanka (Related to Selected Newspaper Media from April of 1983 to September of 1983)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 1, Ver. 8 (January. 2018) PP 25-33 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media performance in Sri Lanka (Related to selected Newspaper media from April of 1983 to September of 1983) Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Department of Political Science University of Kelaniya Kelaniya Corresponding Author: Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Abstract: The strong contribution denoted by media, in order to create various psychological printings to contemporary folk consciousness within a chaotic society which is consist of an ethnic conflict is extremely unique. Knowingly or unknowingly media has directly influenced on intensification of ethnic conflict which was the greatest calamity in the country inherited to a more than three decades history. At the end of 1970th decade, the newspaper became as the only media which is more familiar and which can heavily influence on public. The incident that the brutal murder of 13 military officers becoming victims of terrorists on 23rd of 1983 can be identified as a decisive turning point within the ethnic conflict among Sinhalese and Tamils. The local newspaper reporting on this case guided to an ethnical distance among Sinhalese and Tamils. It is expected from this investigation, to identify the newspaper reporting on the case of assassination of 13 military officers on 23rd of July 1983 and to investigate whether that the government and privet newspaper media installations manipulated their own media reporting accordingly to professional ethics and media principles. The data has investigative presented based on primary and secondary data under the case study method related with selected newspapers published on July of 1983, It will be surely proven that journalists did not acted to guide the folk consciousness as to grow ethnical cordiality and mutual trust. -

Chandrika Kumaratunga (Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga)

Chandrika Kumaratunga (Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga) Sri Lanka, Presidenta de la República; ex primera ministra Duración del mandato: 12 de Noviembre de 1994 - de de Nacimiento: Colombo, Western Province, 29 de Junio de 1945 Partido político: SLNP ResumenLa presidenta de Sri Lanka entre 1994 y 2005 fue el último eslabón de una dinastía de políticos que, como es característico en Asia Indostánica, está familiarizada con el poder tanto como la tragedia. Huérfana del asesinado primer ministro Solomon Bandaranaike, hija de la tres veces primera ministra Sirimavo Bandaranaike ?con la que compartió el Ejecutivo en su primer mandato, protagonizando las dos mujeres un caso único en el mundo- y viuda de un político también asesinado, Chandrika Kumaratunga heredó de aquellos el liderazgo del izquierdista Partido de la Libertad (SLNP) e intentó, infructuosamente, concluir la sangrienta guerra civil con los separatistas tigres tamiles (LTTE), iniciada en 1983, por las vías de una reforma territorial federalizante y la negociación directa. http://www.cidob.org 1 of 10 Biografía 1. Educación política al socaire de su madre gobernante 2. Primera presidencia (1994-1999): plan de reforma territorial para terminar con la guerra civil 3. Segunda presidencia (1999-2005): proceso de negociación con los tigres tamiles y forcejeos con el Gobierno del EJP 1. Educación política al socaire de su madre gobernante Único caso de estadista, mujer u hombre, hija a su vez de estadistas en una república moderna, la suya es la familia más ilustre de la élite dirigente -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

The 35Th Annual Conference on South Asia (2006) Paper Abstracts

35th Conference on South Asia October 20 – 22, 2006 Accardi, Dean Lal Ded: Questioning Identities in Fourteenth Century Kashmir In this paper, I aim to move beyond tropes of communalism and syncretism through nuanced attention to Indian devotional forms and, more specifically, to the life and work of a prominent female saint from fourteenth century Kashmir: Lal Ded. She was witness to a period of great religious fermentation in which various currents of religious thought, particularly Shaiva and Sufi, were in vibrant exchange. This paper examines Lal Ded’s biography and her poetic compositions in order to understand how she navigated among competing traditions to articulate both her religious and her gender identity. By investigating both poetic and hagiographic literatures, I argue that Lal Ded’s negotiation of Shaivism and Sufism should not be read as crudely syncretic, but rather as offering a critical perspective on both devotional traditions. Finally, I also look to the reception history of Lal Ded’s poetry to problematize notions of intended audience and the communal reception of oral literature. Adarkar, Aditya True Vows Gone Awry: Identity and Disguise in the Karna Narrative When read in the context of the other myths in the Mahabharata and in the South Asian tradition, the Karna narrative becomes a reflection on the interdependency of identity and ritual. This paper will focus on how Karna (ironically) negotiates a stable personal identity through, and because of, disguised identities, all the while remaining true to his vows and promises. His narrative reflects on the nature of identity, self-invention, and the ways in which divinities test mortals and the principles that constitute their personal identities. -

US Job Loss Far Worse Than Indicated

OPPOSITION TO MOVE COURT POLITICAL MATURITY OF OVER PARLIAMENT RECALL SRI LANKA'S LEADERS PUT TO THE TEST MAY THE POWER 01 - 03, 2020 OF PAPER VOL: 4- ISSUE 193 . 30 ‘UTTER DISASTER' PASSIONS AND GLOCAL PAGE 03 HOT TOPICS PAGE 04 COMMENTARY PAGE 06 PERSONALITIES PAGE 08 Registered in the Department of Posts of Sri Lanka under No: QD/144/News/2020 COVID-19 and curfew in Sri Lanka • 14 people were confirmed as COVID-19 positive yester- day (April 30), taking Sri Lanka’s tally of the novel coro- navirus infection to 663. 502 individuals are receiving treatment, 154 have been deemed completely recovered and seven have succumbed to the virus. • An all island curfew was imposed from 8:00 p.m. yes- terday till 5:00 a.m. Monday (4). • Of the 997 navy personnel tested for COVID-19, 159 were confirmed as positive with 80% being asympto- matic. • Of the 21,000 PCR tests carried out in Sri Lanka so far, 3% have been confirmed as positive. • The Civil Aviation Authority has invited drone opera- tors to join the fight against COVID-19. • Police say no decision has been taken so far to extend the curfew in areas deemed as high risk, till May 31 though it was announced that curfew passes issued for essential services that ended yesterday could be used till the end of May. • Postmaster General RanjithAriyaratne has announced that all post offices will be opened from Monday for reg- ular services. He has requested public to follow health advices when visiting post offices and obtaining services. -

10Th Session 2009

IS THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY AWARE OF THE GENOCIDE OF TAMILS? APPEAL TO THE UN HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL APPEL À LA PRISE DE CONSCIENCE DU CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L 'H OMME - NATIONS UNIES LLAMADO PARA REACCIÓN URGENTE DEL CONSEJO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS -NACIONES UNIDAS WEBSITE : www.tchr.net 10th session / 10ème session / 10° período de sesiones 02/03/2009 -- 27/03/2009 TAMIL CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS - TCHR CENTRE TAMOUL POUR LES DROITS DE L 'H OMME - CTDH CENTRO TAMIL PARA LOS DERECHOS HUMANOS (E STABLISHED IN 1990) HYPOCRISY OF MAHINDA RAJAPAKSA “T HERE IS NO ETHNIC CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA AS SOME MEDIA MISTAKENLY HIGHLIGHT ” MAHINDA RAJAPAKSA TO THE LOS ANGELES WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL – 28 SEPTEMBER 2007 “Ladies and Gentlemen, our goal remains a negotiated and honourable end to this unfortunate conflict in Sri Lanka. Our goal is to restore democracy and the rule of law to all the people of our country. 54% of Sri Lanka’s Tamil population now lives in areas other than the north and the east of the country, among the Sinhalese and other communities. There is no ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka - as some media mistakenly highlight. Sri Lanka’s security forces are fighting a terrorist group, not a particular community.” “I see no military solution to the conflict. The current military operations are only intended to exert pressure on the LTTE to convince them that terrorism cannot bring them victory.” (Excerpt) http://www.president.gov.lk/speech_latest_28_09_2007.asp * * * * * “....W E ARE EQUALLY COMMITTED TO SEEKING A NEGOTIATED AND SUSTAINABLE SOLUTION TO THE CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA ” MAHINDA RAJAPAKSA TO THE HINDUSTAN TIMES LEADERSHIP SUMMIT AT NEW DELHI ON 13 OCTOBER 2007 “It is necessary for me to repeat here that while my Government remains determined to fight terrorism, we are equally committed to seeking a negotiated and sustainable solution to the conflict in Sri Lanka. -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999 INTRODUCTION This union list updates African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries compiled by Daniel A. Britz, Working Paper no. 8 African Studies Center, Boston, 1979. The holdings of 19 collections and the Foreign Newspapers Microfilm Project were surveyed during the summer of 1999. Material collected currently by Library of Congress, Nairobi (marked DLC#) is separated from the material which Nairobi sends to Library of Congress in Washington. The decision was made to exclude North African papers. These are included in Middle Eastern lists and in many of the reporting libraries entirely separate division handles them. Criteria for inclusion of titles on this list were basically in accord with the UNESCO definition of general interest newspapers. However, a number of titles were included that do not clearly fit into this definition such as religious newspapers from Southern Africa, and labor union and political party papers. Daily and less frequently published newspapers have been included. Frequency is noted when known. Sunday editions are listed separately only if the name of the Sunday edition is completely different from the weekday edition or if libraries take only the Sunday or only the weekday edition. Microfilm titles are included when known. Some titles may be included by one library, which in other libraries are listed as serials and, therefore, not recorded. In addition to enabling researchers to locate African newspapers, this list can be used to rationalize African newspaper subscriptions of American libraries. It is hoped that this list will both help in the identification of gaps and allow for some economy where there is substantial duplication. -

Family Planning in Ceylon1

1 [This book chapter authored by Shelton Upatissa Kodikara, was transcribed by Dr. Sachi Sri Kantha, Tokyo, from the original text for digital preservation, on July 20, 2021.] FAMILY PLANNING IN CEYLON1 by S.U. Kodikara Chapter in: The Politics of Family Planning in the Third World, edited by T.E.Smith, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1973, pp 291-334. Note by Sachi: I provide foot note 1, at the beginning, as it appears in the published form. The remaining foot notes 2 – 235 are transcribed at the end of the article. The dots and words in italics, that appear in the text are as in the original. No deletions are made during transcription. Three tables which accompany the article are scanned separately and provided. Table 1: Ceylon: population growth, 1871-1971. Table 2: National Family Planning Programme: number of clinics and clinic-population ratio by Superintendent of Health Service (SHS) Area, 1968-9. Table 3: Ceylon: births, deaths and natural increase per 1000 persons living, by ethnic group. The Table numbers in the scans, appear as they are published in the book; Table XII, Table XIII and Table XIV. These are NOT altered in the transcribed text. Foot Note 1: In this chapter the following abbreviations are used: FPA, Family 2 Planning Association, LSSP, Lanka Samasamaja Party, MOH, Medical Officer of Health, SLFP, Sri Lanka Freedom Party; SHS, Superintendent of Health Services; UNP, United National Party. Article Proper The population of Ceylon has grown rapidly over the last 100 years, increasing more than four-fold between 1871 and 1971. -

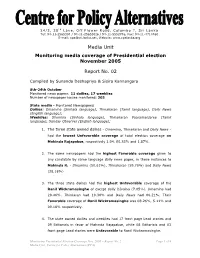

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

Economic and Social Statistics

ECONOMIC & SOCIAL STATISTICS OF SRI LAI,IKA STATISTICS DEPARTMENT CENTRAL BANK O[' SRI LAI\IKA coLoMBo,.sRI LAI\KA. DECEMBER, 1995. lSBil e55 - 575 - 030 - 0 $ Prlnted ot thc Oentrcl Br,nk Prlnttng Ptas ECONOMIC & SOCIAL STATISTICS OF SRI LANKA - 1994 CONTENTS I. CLIMATE 4.3 Tea 22 4.4 Rubber 23 l. I Mean Temperature I 4.5 Coconut 24 1.2 Rainfall 2 4.6 Other Food Crops 25 1.3 Number of Rainy Days 3 4.7 Minor Export Crops 26 1.4 Humidity 4 4.8 Fish and Livestock 27 4.9 Fertilizer 2. POPULATION 28 & EMPLOYMENT 4.10 Settlement and New Land Cultivated under Mahaweli Programme 29 4. Granted under Refinance 2.1 Vital Statistics: Sri Lanka Compared with Selected Counrries 5 I I Cultivation Loans Credit Schemes 30 2.2 Population 6 2.3 Population by Districts and Sectors 7 5. INDUSTRY 2.4 Percentage Distribution of Population by Religion Industrial Activities: Sri Lanka Compared with Selected Countries & Ethnicity 198 | 8 5.1 3l - 5.2 Industrial Production 2.5 Percentage Distribution of Population by Religion 32 5.3 Petroleum & Ethnicity l88l - l98l 9 33 2.6 Vital Statistics l0 5.4 Electricity 34 5.5 Textilcs 2.7 Crude Birth Rates & Death Rates by Districts ll 35 2.8 Population Density t2 5.6 Milk & Milk Products 36 2.9 Labour Force, Employment and Unemployment t3 5.7 Minerals 37 5.8 Ceramics 38 5.9 Sugar 39 3. NATIONAL ACCOT'NTS 5.10 Cement 40 3. I National Accounts Indicators: Sri Lanka Compared with 5.1 I Steel 4l i Selected Countries l4 5.12 Tyres 42 I 3.2 National Accounts Summary 5. -

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: the ROOTS of PLURALISM BREAKDOWN

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: THE ROOTS OF PLURALISM BREAKDOWN Neil DeVotta | Wake Forest University April 2017 I. INTRODUCTION when seeking power; and the sectarian violence that congealed and hardened attitudes over time Sri Lanka represents a classic case of a country all contributed to majoritarianism. Multiple degenerating on the ethnic and political fronts issues including colonialism, a sense of Sinhalese when pluralism is deliberately eschewed. At Buddhist entitlement rooted in mytho-history, independence in 1948, Sinhalese elites fully economic grievances, politics, nationalism and understood that marginalizing the Tamil minority communal violence all interacting with and was bound to cause this territorialized community stemming from each other, pushed the island to eventually hit back, but they succumbed to towards majoritarianism. This, in turn, then led to ethnocentrism and majoritarianism anyway.1 ethnic riots, a civil war accompanied by terrorism What were the factors that motivated them to do that ultimately killed over 100,000 people, so? There is no single explanation for why Sri democratic regression, accusations of war crimes Lanka failed to embrace pluralism: a Buddhist and authoritarianism. revival in reaction to colonialism that allowed Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists to combine their The new government led by President community’s socio-economic grievances with Maithripala Sirisena, which came to power in ethnic and religious identities; the absence of January 2015, has managed to extricate itself minority guarantees in the Constitution, based from this authoritarianism and is now trying to on the Soulbury Commission the British set up revive democratic institutions promoting good prior to granting the island independence; political governance and a degree of pluralism.