Chelsea May Vowel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmund Morris Among the Saskatchewan Indians and the Fort Qu'appelle Monument

EDMUND MORRIS AMONG THE SASKATCHEWAN INDIANS AND THE FORT QU'APPELLE MONUMENT By Jean McGill n 1872 the government of Canada appointed Alexander Morris the first Chief Justice of Manitoba. The same year he succeeded A. G. Archibald as Lieu I tenant-Governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Archibald had already acted as a commissioner of the federal government in negotiating Treaties Nos. 1 and 2 with the Indians of Manitoba. Morris was com missioned in 1873 to carry on negotiations with Indians of the western plains and some Manitoba Indians not present at the first two treaties. By the time Alexander Morris's term of office had expired in 1877 he had negotiated the signing of Treaties No. 3 (North-West Angle), 4 (Fort Qu'Appelle), 5 (Lake Winnipeg), 6 (Forts Carlton and Pitt), and the Revision of Treaties Nos. 1 and 2. Morris later documented the meetings, negotiations, and wording of all of the treaties completed prior to 1900 in a book entitled The Treaties of Canada with the Indians ofManitoba and the North west Territories which was published in 1888. He returned to Toronto with his family and later was persuaded to run for office in the Ontario legislature where he represented Toronto for a number of years. Edmund Morris, youngest of a family of eleven, was born two years before the family went to Manitoba. Indian chiefs and headmen in colourful regalia frequently came to call on the Governor and as a child at Government House in Winnipeg, Edmund was exposed to Indian culture for the Indians invariably brought gifts, often for Mrs. -

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

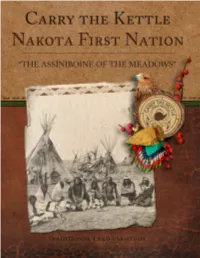

CTK-First-Nations Glimpse

CARRY THE KETTLE NAKOTA FIRST NATION Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study JIM TANNER, PhD., DAVID R. MILLER, PhD., TRACEY TANNER, M.A., AND PEGGY MARTIN MCGUIRE, PhD. On the cover Front Cover: Fort Walsh-1878: Grizzly Bear, Mosquito, Lean Man, Man Who Took the Coat, Is Not a Young Man, One Who Chops Wood, Little Mountain, and Long Lodge. Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study Authors: Jim Tanner, PhD., David R. Miller, PhD., Tracey Tanner, M.A., and Peggy Martin McGuire, PhD. ISBN# 978-0-9696693-9-5 Published by: Nicomacian Press Copyright @ 2017 by Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation This publication has been produced for informational and educational purposes only. It is part of the consultation and reconciliation process for Aboriginal and Treaty rights in Canada and is not for profit or other commercial purposes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without the written permission of the Carry the Kettle First Nation, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews. Layout and design by Muse Design Inc., Calgary, Alberta. Printing by XL Print and Design, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Table of Figures 3 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Chief 4 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Councillor Kurt Adams 5 Elder and Land User Interviewees 6 Preface 9 Introduction 11 PART 1: THE HISTORY CHAPTER 1: EARLY LAND USE OF THE NAKOTA PEOPLES 16 Creation Legend 16 Archaeological Evidence 18 Early -

Chief Payipwat Biography

Payipwat (1816-1908) Payipwat signed Treaty Number Four in 1875. He argued for land that was promised to him, and it is said that many of his requests were written into Treaty Number Six in 1876. Payipwat, given the name of Kisikawasan at birth, was a Plains Cree born around the southwestern Manitoba or eastern Saskatchewan area in about 1816. As a boy, he and his grandmother were taken prisoner by the Sioux. He grew into manhood with the Sioux people and learned their medicine until he was rescued by the Cree in the 1830s and returned to his people. Upon his return, he was given the name “Payipwat”, often referred to as Piapot or “Hole in the Sioux”. His name translated as “One Who Knows the Secrets of the Sioux”. Payipwat became a highly respected leader among his people and surrounding bands, and in 1875, he signed Treaty Number Four. The treaty was to be a preliminary negotiation, as Payipwat insisted that the treaty must contain a number of additional provisions, but the provisions were never written in. While on the allotted reserve in 1883, there was a disappearance of the bison. That year became a year of sickness and starvation among the people, and this convinced Payipwat to argue for the establishment of a large Indian territory among Cypress Hills. During this time, the federal government began to withhold rations, forcing the Plains Cree to forfeit their resistance and settle into their small reserves. Though the large piece of land was never received, Payipwat managed to negotiate a better location in the Qu’Appelle Valley in 1884. -

Reclaiming Nêhiyaw Governance in the Territory of Maskwacîs Through Wâhkôtowin (Kinship)

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-24-2017 12:00 AM E-kawôtiniket 1876: Reclaiming Nêhiyaw Governance in the Territory of Maskwacîs through Wâhkôtowin (Kinship) Paulina R. Johnson The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Regna Darnell The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Paulina R. Johnson 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Johnson, Paulina R., "E-kawôtiniket 1876: Reclaiming Nêhiyaw Governance in the Territory of Maskwacîs through Wâhkôtowin (Kinship)" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4492. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4492 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Nêhiyawak, Four-Body People, known as the Plains Cree, reside in the territory of Maskwacîs. Of the Four Nations that encompass Maskwacis, this study focuses on Nipisihkopahk, also known as Samson Cree Nation and is located 70km south of the city of Edmonton in Alberta. Governance for the Nêhiyawak lies in the philosophical and spiritual teachings passed down through generations of ancestral knowledge especially in discussions relating to wâhkôtowin, kinship, ohtaskanesowin, origin, and the teachings from Wîsahêcâhk, Elder Brother, who taught the Nêhiyawak about morality and self through oral narratives. As relationships between the settler state of Canada and Indigenous Nations create dialogue concerning authority and autonomy, this study discusses the methods utilized through community collaboration for the process of enacting traditional governance. -

Analysis Report

Analysis Report WHETHER TO DESIGNATE THE NINE AGRICULTURAL DRAINAGE NETWORK PROJECTS IN SASKATCHEWAN December 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 PROJECTS .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 CONTEXT OF REQUESTS ..................................................................................................................................... 2 PROJECT CONTEXT ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Components and Activities ............................................................................................................... 5 Blackbird Creek Drainage Network (Red/Assiniboine River watershed) ........................................................... 5 Saline Lake Drainage Network (Upper Assiniboine River watershed) ............................................................... 6 600 Creek Drainage Network (Lower Souris River watershed) ......................................................................... 6 Vipond Drainage Network (Moose Mountain Lake and Lower Souris River watersheds) -

Canada's Subjugation of the Plains Cree, 1879–1885

JOHN L. TOBIAS Canada'sSubjugation of thePlains Cree,ß 879- 885 ONEOF THE MOST PERSISTENT MYTHS that Canadianhistorians perpetuate is that of the honourableand just policyCanada followed in dealing with the PlainsIndians. First enunciatedin the Canadianexpansionist literature of the 187os as a means to emphasizethe distinctive Canadianapproach to and the uniquecharacter of the Canadianwest, 1 it hasbeen given credence by G.F.G. Stanleyin his classicThe Birth of WesternCanada, • and by all those who use Stanley'swork as the standardinterpretation of Canada'srelationship with the PlainsIndians in the period 187o-85. Thus studentsare taughtthat the Canadian governmentwas paternalistic and far-sightedin offeringthe Indiansa meansto becomecivilized and assimilatedinto white societyby the reservesystem, and honest and fair-minded in honouring legal commitmentsmade in the treaties.• The PlainsIndians, and particu- larly the PlainsCree, are saidto be a primitivepeople adhering to an inflexiblesystem of traditionand custom,seeking to protectthemselves againstthe advanceof civilization,and takingup armsin rejectionof the reservesystem and an agriculturalway of life.4 This traditional Doug Owram, Promiseof Eden: The Canadian Expansionist Movement and the Idea of the West,•856-•9oo (Toronto •98o), •3•-4 G.F.G. Stanley,The Birth of WesternCanada: A Historyof theRiel Rebellions(Toronto •96o) Ibid., 2o6-• 5 Ibid., vii-viii, • 96, 2 • 6-36. It shouldbe noted that the traditionalinterpretation of a Cree rebellionin associationwith the Metis hasbeen challenged by R. Allen, 'Big Bear,' SaskatchewanHistory, xxv (•972); W.B. Fraser,'Big Bear, Indian Patriot,'Alberta Historical Review, x•v 0966), •-• 3; Rudy Wiebe in his fictional biography,The Temptations ofBig Bear (Toronto •973) and in hisbiography of Big Bear in the Dictionaryof CanadianBiography [r•cB], x•, •88•-9o (Toronto •982), 597-6o •; and NormaSluman, Poundmaker (Toronto • 967). -

Report of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police, 1915

6 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1916 REPORT OF THE ROYAL NORTHWEST MOUNTED POLICE 19 15 PRIXTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT. OTTAWA PRIXTED BY J. i)E L. TACHE, PRINTER TO THE KING S M03T EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1915 [No. 28—1916.] 4 f 6 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1916 The Field Marshal His Royal Highness the Duke of Connaughi and of Stratheam, K.Q., K.T., K.P., etc., etc., etc., Oovemor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. May it Please Your Eoyal Highness : The undersigned has the honour to present to Your Royal Highness the Annual Eeport of the Eoyal Northwest Mounted Police for the year 1915. Eespectfully submitted, E. L. BOEDEiSr, President of the Council ^ November 17, 1915. 28—li I 6 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1916 TABLE OF CONTENTS r A i; r i. Page. Commissioner's Report, 191.) 7 Appendices to the above. Appendix A.—Superintendent J. A. lle( ribbon, Kegina District 27 B.—Superintendent W. H. Koutledge, Prince Albert : . 56 C.—Superintendent C. Starnes, Maeleod. 72 D.— Superintendent T. A. Wroughton, Edmonton !•() E.—Superintendent F. J. A. Demers, Maple Creeli 10-1 F.— Superintendent F. J. Horrigan, Calgary 118 13'J Gr.—Superintendent A. E. C. McDonell, Athabaska Landing H.— Superintendent C. H. West, Battleford 154 169 J,.—Superintendent G. S. Worsley, "Depot" Division K—Superintendent G. S. Worsley, "Reserve" Division 174 L.—Superintendent P. W. Pennefather, Lethbridge 177 M.—Inspector J. W. Phillips, Mackenzie River Sub-district 189 N.—Asst. Surgeon J. -

Aboriginal and Colonial Geographies of the File Hills Farm Colony

Aboriginal and Colonial Geographies of the File Hills Farm Colony by C Drew Bednasek A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada October 2009 Copyright © C Drew Bednasek Abstract Canadian government archives have primarily shaped scholars’ analysis of the File Hills farm colony on the Peepeekisis Reserve in south eastern Saskatchewan. While these colonial archives are valuable for research, they emphasise particular points in the government’s telling of the colony story. They focus on the construction, management, and intentions of the colony, but neglect the experiences and perspectives of Peepeekisis community members affected by the colony scheme. My thesis makes use of government archives, and is also based on Aboriginal oral histories about the colony and its long-term consequences. My central argument is that a more critical interpretation of archives and oral histories will enrich the historical and geographical record about the colony. I demonstrate how oral histories and archive documents can converge and diverge, but combining the two is particularly important to nuance the colony narrative. A critical viewing of texts and oral histories from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries also reveals that colonialism in the prairie west was highly spatalised and grounded in “betterment” sciences that sought to control and discipline Aboriginal peoples through the manipulation of space, heredity, and environments. Betterment sciences shaped Indian Affairs policy and the farm colony is a remarkable example of how betterment was applied on the ground. Finally, oral histories offer powerful insight into Aboriginal identities that survive in spite of colonial constructs and strategies. -

As Practiced by the Plains Cree and Saulteaux of the Pasqua Reserve, Saskatchewan, in Their Contemporary W Dance Ceremones

A Description and Analysis of Sacrificial Stall Dancing: As Practiced by the Plains Cree and Saulteaux of the Pasqua Reserve, Saskatchewan, in their Contemporary Rain Dance Ceremonies A Thesis Subrnitred to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Native Studies at the University of Manitoba by Randall J. Brown Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright, 1996. R. J. Brown National Library Bibliothèque nationale I*B of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON KlAON4 OnawaON KtAON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou cûpies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/- de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~$$t in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fi-om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. FACULTY OF GROUATE STUDXES ta*++ COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE A DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSlS OF SACRfFICLAL STALL DANCING AS PRACTICED BY THE PLAINS CREE AND SAULTEAUX OF THE PASQUA RESERVE, SASKATCHEWAN, IN THEIR CONTEMPORARY W DANCE CEREMONES RANDALL J. -

Mediating the Numbered Treaties: Eyewitness Accounts of Treaties

Mediating the Numbered Treaties: Eyewitness Accounts of Treaties Between the Crown and Indigenous Peoples, 1871-1876 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Special Case Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Regina by Sheldon Kirk Krasowski Regina, Saskatchewan June 2011 Copyright 2011: Sheldon Krasowski Abstract This thesis looks at the historical period of treaty-making in Western Canada when six numbered treaties were negotiated between Canada and the Anishnabeg, Cree, Saulteaux, and Assiniboine Nations between 1871 and 1876. The main interpretation of treaty-making during this period is that the treaty commissioners and Indigenous leadership experienced “cultural misunderstandings” and that Euro-Canadian witnesses to treaty did not understand the treaty relationship. As a result, most of the eyewitness accounts by Euro-Canadian fur traders, missionaries, journalists, settlers and government representatives have been ignored by historians. This thesis argues against cultural misunderstandings and shows that Euro-Canadian negotiators and eyewitnesses clearly understood the roles and responsibilities in the treaty relationship. Violations of treaty did occur as new settlers moved into treaty territory and government representatives became more concerned about financial restrictions than the promises made during the negotiations. However, during the treaty-making period, Euro-Canadians understood their obligations under the treaty relationship. This thesis analyzes previously under- utilized primary documents and re-evaluates standard sources on the numbered treaties to show that during the treaty-making period, Euro-Canadians understood the expectations of Indigenous peoples in the treaty relationship. i Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor and committee members. -

The Numbered Treaties, Indian Act, Andloss of Aboriginal Autonomy

Relations between Canada and First Nations in the West (1867- 1900): The Numbered Treaties, Indian Act, andLoss of Aboriginal Autonomy Year Level: HIST 3730 Citation Style: Chicago Relations between Canada and First Nations in the West (1867-1900) In 1887, Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald declared that “the great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and to assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion.” 1 After Confederation in 1867, the Canadian federal government held the belief that First Nations groups were impediments to economic, political, and social development in the West. In order to overcome the “Indian Problem” as once stated by Duncan Campbell Scott, the government negotiated a set of seven treaties called the Numbered Treaties withthe First Nations throughout the West between 1871 and 1877.Although no First Nations groups were particularly comfortable about ceding their traditional territories to the government, problems like mass starvation, epidemics, and new immigrants highly influenced their final decision. These treaties were unknowingly, the preliminary stages of assimilating the Aboriginal population into Euro-Canadian society and securing the frontier. In order to further assimilate these vulnerable First Nations groups to become fully participating members of Euro- Canadian society, the Indian Act was passed in 1876 by the Government of Canada. Although a certain degree of resistance was present throughout many treaty negotiations, the Numbered Treatieswere largely viewed by the First Nations as a fair compromise when faced with potential consequences such as possessing no land title and enduring starvation.